Tuning Away from Mechanized Listening features Midwest’s music ecosystems—listening cultures where thoughtful curation, collective engagement, and storytelling still shape what and how we hear. This series is meant to be a reminder: listening can be more than a passive, forgetful experience.

The interview with Teddy Sandler was recorded in person, then edited and transcribed.

Livy Onalee Snyder (LS): First off, I just want to make sure I have the correct name of the retreat—it’s a retreat, right?

Teddy Sandler (TS): Yes. But I’ve started to frame it differently in my mind. The retreat was called Sonic Resonance, but it almost felt more like a residency. We went out to Wisconsin—it was freezing, dipping into the 40s—but that kind of made everyone bond. Yej Yoon, the chef, was incredible. Their cooking was exceptional and totally changed the energy of the weekend. Everyone bundled up, the nightlife glamor dropped away, and it felt really low-stakes and communal. We all shared rooms in one big house, and it created this sense of closeness that carried through the whole weekend.

LS: And how did you get involved? How did you meet the organizers?

TS: They invited me as a curator and at the last minute, I, along with one other person [Max Li] were brought in as producers—mainly to be an extra line of support. It was really awesome to be in those organizing meetings and also in the curator[ial] meetings beforehand, just seeing how everything came together. The event organizers are amazing—they do a lot of arts programming and are getting more into music, but it all stemmed from a documentary they’re making about Chicago House Music, a collaboration between Rory Leighton and William Yung. They’ve been filming around the city and showing little snippets here and there. They actually filmed at one of my events before!.

LS: So what did the planning meetings, you mentioned, look like? And if I understand correctly, you also led one of the sessions. How was that? What did you want to prioritize?

TS: Early on, when they were putting together the lineup of curators, I was like, this is wild. I knew they were inviting some people who weren’t necessarily DJs to teach, but when I saw the other DJs on the list, I realized they’d been working in the electronic scene for years.

I’ve really only been active for about three years—basically since things reopened after lockdown, which is when I turned 21. I was at every party and started getting more deeply involved. But it’s really been the last two years that I’ve been helping plan and organize events. So I was really grateful. When I saw my name next to these other people, I was like, cool. It’s so awesome.

LS: I love it. And did they get to attend your course, too?

TS: Yes. We were all going to everyone’s classes. It was semi-structured and very flexible: you didn’t have to go, [but] come and go as you please. Basically everyone came to every course. And stuck around the whole time.

My course was definitely a lot more free-flowing than the others. The others were like, we’re sitting in the unheated barns and we were like, learning something, watching old footage, a demonstration, or practicing as a group.

LS: Where did your course take place?

TS: I started in the barn and didn’t have any visuals. I gave a small introduction, and then I was like, come on, y’all, we’re going on a walk.

LS: What was the course called?

TS: Actually, I didn’t give it a name. I described it to the event organizers, and they were like, oh so we’re going on a sound walk.

It was a course on the sound—or at least that was the guiding framework or methodology I was working within. That was the main activity. If I can do a little revisionist history, it was really about active listening and developing attunement—for recording, documenting, and preserving sound.

LS: What a great focus. Tell me how you got to the point of deciding to lead a course on active listening.

TS: When Rory and Will were talking to me about what courses could look like, they were like we want to utilize the camp grounds and the fact we went to Wisconsin. I mean we are a bunch of artists living in the city and this was finally an opportunity to step outside of our big metropolitan lives. A lot of these courses could have taken place anywhere but I wanted to get outside and use the location that we were in. And I was kind of the only one who did that. As I literally got everyone out into nature and I made them take a walk.

LS: Walk me through your sound walk (haha) and how it impacted your practice. Specifically, how was your practice impacted by experiencing the sound walk with the other DJs?

TS: I’m from a major city [NYC] and then moved to another one. I’ve been on road trips and hiked in forests, but I’ve never actually stayed on a farm until Wisconsin. I didn’t realize how new that experience would feel. After the three-hour car ride, most people were tired and lounging quietly, but I was immediately energized. I dropped my bags, looked around, and thought, this is so cool. It was the one warm day, so I didn’t even need a coat. I walked the grounds of the event space, exploring the landscape, partly out of curiosity and partly as training. It was gorgeous. I got so inspired—literally running through the fields. I don’t run, ever, maybe to catch a bus or train, but that day I was just full of unbridled joy to be out in nature in a place so new to me.

Sound-wise, that first day I was just absorbing everything, letting myself feel instead of analyzing. I’ve been training in active listening for at least four years—really, for as long as I’ve understood music. But that day wasn’t about dissecting sound; it was about letting instinct lead. As an artist, sometimes you just have to turn off your brain and be present. My favorite quote—one I always come back to—is from Duchamp. When asked about his artistic practice, he said, “I just breathe.” That’s exactly how I felt out there, just breathing, feeling, existing. Looking back, I wish I recorded more; I was so inspired. Now, every day I wake up attuned to soundscapes around me, wanting to capture them.

TS: When designing the course, I struggled with where to begin. I didn’t want people to just walk aimlessly—I wanted to give them questions that would guide their attention while still leaving room for wandering and discovery. Rather than lecturing about sound history, I wanted to demonstrate listening itself. One of the main influences was John Cage’s 4’33”, which I think is a perfect entry point to active listening. I even joked with the organizers that I’d start my session by walking up to the DJ booth, plugging in my USB, and just standing there for four minutes and thirty-three seconds—but then I thought, no, let’s take it into nature first.

But I did do that. I led everyone to like a small fire pit, not saying anything. They all gathered around me and I stood there, we stood there, for four minutes and 33 seconds of me asking them without speaking to just like, listen.

LS: Did they love it?

TS: At first it took people a while to get into it. In my mind, I was like: are we just suffering? It was cold, and being outside felt terrible at first. But by the end, people were coming up to me saying, “I needed that.” The cold, the discomfort, being out in nature—all of it helped us push through those awkward early moments and really start listening.

To walk you through it, before those first four minutes, I needed to set things up. I opened with the concept of recorded sound—when we, as humans, first learned how to capture it. We started with early examples, literally with sheet music, and built up from there into records and playback. From that point, I gave a very brief history of what those developments led to, and I approached it through the lens of birds.

I’ve always been drawn to birds; I even have a playlist of bird tracks I’ve collected. There’s something profound in the idea that once a species goes extinct, you can never record its sound again. People often talk about how we don’t really know what dinosaurs looked like—we can piece it together from fragments—but imagining how they sounded is even more intangible, almost ethereal.

LS: Well, I can’t deny it, but the first thing that comes to my mind when you say that is the meme about the mummy’s voice. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but scientists reconstructed this mummy’s vocal cords to share a single sound. And there’s the real version. But then, of course, the internet has run with it.

It’s really funny, but I get what you mean about the birds and extinction. And thinking about preserving now, but also what, what we can’t hear from the past and anticipating the future. With that in mind, yes. It is very interesting to think about.

TS: I’m constantly thinking about how soundscapes are intangible—fleeting things that can easily disappear. Chicago sounded different 30 years ago, and it’ll sound different 30 years from now. There are recordings that capture moments, but what really interests me is recording now—drawing attention to sounds that will eventually vanish or that feel essential to this particular moment.

One thing I’ve been inspired to do is build a soundscape: to go to different places—maybe protests, maybe just city streets—capturing people’s whistles and ambient sounds. Chicago sounds different because of all the ICE activity. It has its own distinct texture and I want to help people notice how those sounds change over time, sometimes subtly, sometimes suddenly.

I think about that constantly. In the course, I also looked back at recordings of extinct birds—species that were recorded once and then disappeared. There are other ways of documenting sound beyond recording, too. Before recording technology existed, people translated sounds, like birdsong, into musical notation.

There’s one extinct bird in particular for which we have a musical score—an operatic transcription made before it could ever be recorded. So the only trace of that bird’s sound that remains is this piano score, this written echo of something we’ll never actually hear again.

And one artist brought that score and put it on the gramophone, out on the island where the bird used to live and played it out. And it’s eerie… This tin-y recording of this bird that doesn’t exist anymore. And it’s the last artifacts that we have a bit solemn and like, that’s that’s cool. Like, what are these other ways that we can document, what even makes the soundscape?

I just wanted people to really tune in—that’s where I started. After the initial four minutes and thirty-three seconds, I asked everyone what they heard. One of my friends said something that stuck with me—not from this retreat, but earlier—they mentioned how comedic timing relies on knowing when to pause and leave silence. That really resonated with me.

By the end, someone said, “That was crazy—but cool.” I wanted to know what people focused on, what drew their attention. It wasn’t just about the sounds of wind or the general atmosphere, but about orientation in space—the vehicles passing nearby, the planes overhead, the different birds we could hear. I knew wherever we were, there would be birds.

That’s why I planned to start there and then let things unfold naturally. After gathering everyone’s thoughts, I said, “Alright, let’s go,” and we all began walking—mostly in the same direction at first, until people started splitting off and finding their own paths. Some people stayed out there on different paths for a really long time. And that felt really good. They were clearly inspired to do something. And it’s a very intangible skill to get and to train.

And one of those where like being like a music critic and like being in electronic music and then also being a teacher, they’re all things that help, but these come with subtle attunements that are difficult to teach someone to do.

They have to just do it. But you can give people the tools to start thinking about how they’re listening and engaging that sense in their day-to-day life.

LS: I would have absolutely loved your course! I have a couple of questions. Since this was the first time it took place, do you know if there are plans for it to happen again? And I’m also curious about how you think about the term DJ in this context. Who attended—were there both experienced DJs leading as curators and participants who were newer to it? I’m wondering what that word meant to everyone involved in this experience, and how you think those meanings or roles might change in future iterations of the retreat as it continues to evolve.

TS: Yeah, at first it was open to all skill levels but targeted specifically toward beginners, to help them develop foundational skills. Or for people who were already DJing and wanted to refine what they knew. The most surprising thing since then is how many people—at every skill level—have come up to me asking about it. Some are very experienced DJs, people I’d expect to be teaching rather than taking the course, saying, “Can I apply next year as a student?”

LS: No matter your experience, there are those skills everyone wants to strengthen. DJing is like a muscle—you have to keep training, using, and activating it. When you do that in different contexts and periods of your life, it’s always evolving. It’s about practice.

TS: And it’s about creating a space for collaboration, which is often missing in nightlife. Real connection—actually knowing people—is rare. It’s easy to say hi to a lot of people during a night out, with or without substances, but forming deeper relationships beyond that is harder.

Some cities do this better than others. Berlin, for example, has strong ties between music, art, and community. There, scenes grow around music no matter the setting or substances. Chicago has that too—I have friends I collaborate with outside the club, and those friendships inspire projects we bring into nightlife. But that’s not always the case. There are plenty of people I’d love to work with in nightlife who I’m not as close to during the day—it’s just different levels of connection.

Another thing that inspired me is how the landscape of music is changing. On streaming platforms, the “song fader” works almost as well as a DJ. There’s AI music now, too. Music can easily fade into the background—always playing, but how much are we really listening?

What plays in the background still shapes how we think and feel, often in subtle ways we don’t consciously notice. My favorite kind of music, or DJ set, is one you can hear from another room and still feel its presence influencing conversation, mood, and movement. Even when I’m DJing—whether at home, in front of friends, or in a club—I’m watching how people respond to small shifts. Laughter, stillness, pauses and those moments show attention in ways people don’t always realize.

With AI-generated music that loops endlessly to rack up streams, the human act of intentionally choosing what comes next becomes even more important. A good DJ doesn’t just keep a steady flow—they build a journey. Even when the sound feels seamless, it’s carefully selected to create continuity and momentum. That intentionality is what’s missing in algorithmic or generative mixes. Bringing that back means creating spaces where people can breathe, listen, and connect.

I do think there will be future iterations of the retreat. I’m not sure what form they’ll take or how much I’ll be involved, but the organizers talked about continuing it, and there’s been great feedback since. Personally, whether or not it happens again, I need to go back out into nature and listen.

On the last day, before we left, two things happened. First, we all recorded a few tracks together, one after another. But before that, I took a long walk—people said I was gone for three hours. I was not gone for that long. I was gone for, like, maybe an hour and a half max. I left my phone, which I kind of regret because I wish I could have recorded things. And I just. Again, wanted to let my ears lead the way. I got lost multiple times. But even while I was lost, I was, like, crouching down and staying in one place very keenly listening to things, and figuring out what made it sound like, like what were the very small things in my environment and painting sonic pictures from that in my own mind.

That’s something I want to keep pursuing. It’s why I call my event series and radio shows –STHESIA—from the root word to feel. I want people to feel things—to feel through listening and through being around others.

LS: I love that. I feel like that’s the perfect way to end. Thank you so much!

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder’s writing has appeared in the Journal for Metal Music Studies, DARIA, Ruckus, TiltWest, Signal, and more. She graduated with her Masters from the University of Chicago in 2021. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and serves on the board of the International Society for Metal Music Studies. Listen to her live on WHPK 88.5 FM Chicago. Read more of Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

About the author: Teddy Sandler is a writer, curator, and sensory artist working alongside electronic music as founder of the show and exhibition series, -STHESIA. She builds speculative worlds to divine positive futurities and is currently creating platforms for affective artists. Catch her DJing as Tdy on 88.5FM Chicago or at bars and clubs around the city.

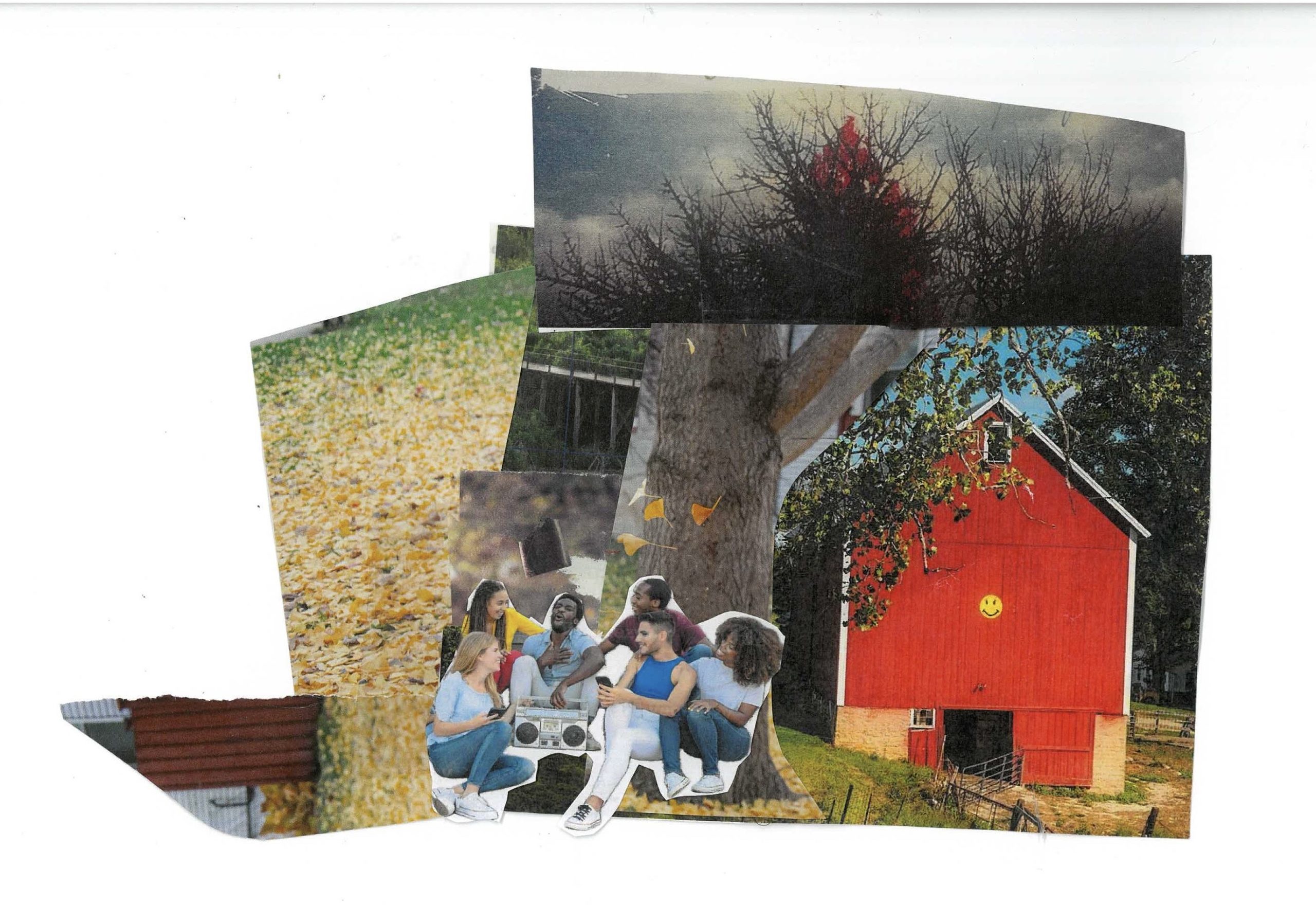

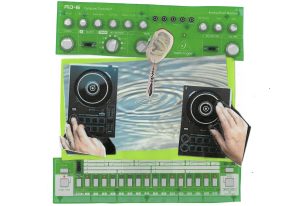

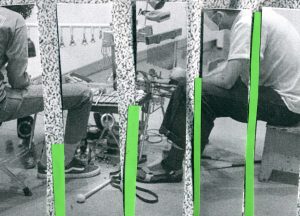

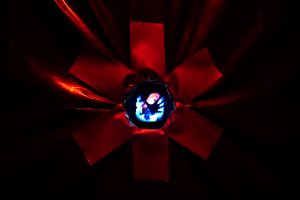

About the illustrator: Bri Robinson is a mixed media artist, analog collagist, sculpture artist, and historian who weaves intricate narratives of love, loss, and identity across the expansive Midwest. Through their unique process of cutting, pasting, and layering, Bri deepens the meaning of these found objects, transforming them into evocative works of art. Bri’s practice is deeply rooted in the exploration of identity, relationships, and the constant evolution of self. By merging archival materials with elements of popular culture, they create thought-provoking narratives that invite viewers to engage with the complexities of the queer experience. Through their work, Bri honors the past while also pushing the boundaries of contemporary art history, crafting pieces that are as introspective as they are expansive. Check out their work on Instagram @niq.uor.