Outfitted in the University of Illinois Chicago’s Gallery 400, Don’t mind if I do, first shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, adventurously models accessibility and accommodation. Organized by the artist Finnegan Shannon, curated by Lauren Leving, and displaying works by Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, Pelenakeke Brown, Sky Cubacub, Ariella Granados, Emilie L. Gossiaux, Felicia Griffin, Joselia Rebekah Hughes, Jeff Kasper, Sandie Yi, and agustine zegers, the exhibition, from its onset, is one enormous inclusive endeavor. It is this explicit dedication to creating art in a collaborative, non-traditional, and inviting manner that is replicated and replayed continuously throughout the show. At every juncture, conceptions of stability tied to normative gallery/museum practices are excavated and undone. Subversive, radical, and disruptive mechanics electrify the space, leaving behind a trail that reminds viewers of the scrutiny that should be (and is) placed on other institutional structures. In an era when vast arrays of discourse from museum studies, disability studies, and art history have theorized how to refashion arts spaces, Don’t mind if I do demonstrates a concrete reality. Unabashedly, and at times hyperbolically, pressing forth, the show delivers on its promise of puncturing a hole in tradition.

Adopting flexibility as its underlying mechanism, the spatial, curatorial, and artistic decisions reflect a propensity for exhibitions to be for all of their attending audiences. Its list of inclusively-minded strategies is endless. Wall text, which appears to your left as you enter the space, is displayed in both Spanish and English (whether this is the gallery’s typical conduct or a specific request by the artist is irrelevant, in either case the motivation is clear). Posters invite (but do not require) guests to wear face masks (freely provided by a friendly gallery attendant) in solidarity with the artists and out of respect for fellow guests. A chipboard mural, which runs across the gallery wall perimeter, graciously and generously references vague collectivity. “We Want to Meet You,” one section says, continuing elsewhere, “We Sit & Enjoy.” These declarations, however ambiguous, gesture towards an activation of space that breaks free from authorial dictations commonly wielded in the “I” format typically found within popular exhibition productions. Where a single curator or organizer once stood, now a connected and interactive grouping resides. Swapping individual power out for communal strength, the multiple phrases open the possibility that viewers, too, might fit easily inside this descriptor. Together, viewers, artists, curators, and organizers combine to form an interactive co-dependent network of creative meaning-makers.

In this authorial exchange of power, the chipboard mural proposes another option for how contextual signifiers materialize in space. While standard wall didactics remain the central evidentiary path, it is these secondary or even tertiary versions—textual placements within the space—that elicit a complementary approach to how a show’s logic can function. Take, for instance, Shannon’s supplemental, highly personal brief that accompanies Leving’s overview. Intent, directly from the artist, adds yet another dimension in regards to how to think through the logic of the space. In inviting viewers to pick up objects, listen to audio descriptions of the work, and enjoy the collection of objects in their own way, Shannon unfurls a single encounter with art by demanding that inherently it carries its own multiplicity. You encounter it how you want. Where else would these overt yet gentle suggestions be extended?

In proposing alternative, non-traditional contextualizations premised on language, the mural and Shannon’s accompanying introduction collectively suggest the “access fantasy,” described in their exhibition’s’s opening wall text. But it might be improper to reduce the show to a fantasy when components within it actualize and reaffirm the practical, very real presence of several productive strategies. There is no fantasy here, only infrastructural blueprints on how to build with access—a starkly different premise than something simply being accessible. Elsewhere in the exhibition, built into one corner of the space, a small bookshelf, coffee table, set of cushions, and rug reconfigure the gallery’s mundanity with relaxed domesticity. Items once common in living quarters populate and comfortingly extinguish the gallery’s sterile environment. Born out of this transformation, an open reading room, and once again Shannon has broadened the social dimensionality of the space, relying upon language to enter discursive and physical realms of approachability.

It is within this warm area that viewers notice the well-crafted spread of literature placed around them. On the coffee table, Crip Authorship: Disability as a Method edited by Mara Mills and Rebecca Sanchez, and lined on the bookshelf, Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire edited by Alice Wong; Feminist, Queer, Crip by Alison Kafer, and Disabled Ecologies: Lessons From A Wounded Desert by Sunaura Taylor, to name only a few. Acting as both a place to rest and a site to academically accentuate the exhibition’s content, the tens of theoretically dense, yet thematically relevant books interceded the privacy of the gallery by demonstrating that the writing within these materials extends beyond the boundaries of the show. Small artworks like the Slow Spin day clocks, placed in several locations around the room, reify this notion, designating which day of the week it is and, in turn, chronologically sync the inside/outside worlds. Where some white walls evaporate the reality from which we later emerge, here the gallery is no stranger to linking lived experiences. Within Gallery 400, the walls are an extension and not an exclusion of daily life.

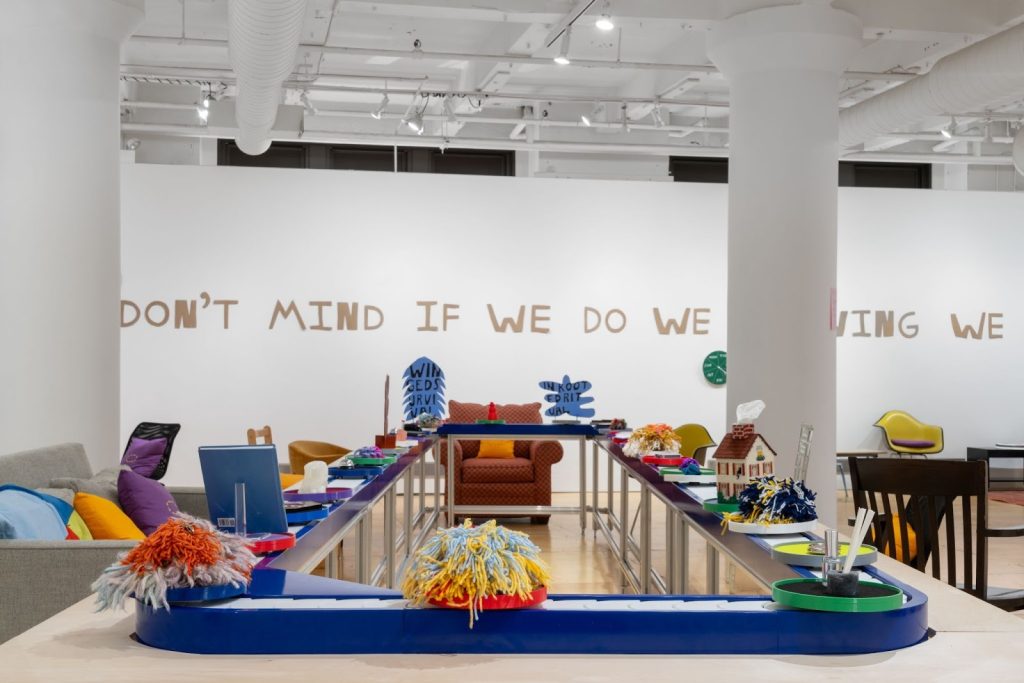

These co-constitutive elements surround the centerpiece of the show, my access fantasy—a conveyor belt on which circular trays, each with items made by one of the collaborating artists in the show—rotate. Lined around its perimeter, seating in various forms allows viewers to comfortably sit while they look upon the spectacle of the looping items. In its mechanical rotation, art is quite literally brought to a viewer’s “plate,” flipping the directional viability of power instilled when viewers must first approach an object in a gallery/museum space. Instead, the delivery system quietly confronts the bodily labor of service located in art. The work of art here is that viewers no longer have to work for their art.

And in line with the magnanimous nature of the exhibition, every object on the course has a corresponding entry in an intentionally designed zine entitled “Writing On: Don’t Mind If I Do,” situating their material, aesthetic, and conceptual origin. All objects are equal, no more valued than the next. As the hum of the motor whirls on, viewers can sit back and enjoy, perhaps finally in a state where one can give the critical thought that art so deserves.

While the construction of space with inclusive and accessible mechanics, antithetical to standard museum practices, is not new, it is refreshing to witness such an embrace of transformative possibility. Shannon endeavors the body politic to be pronounced, or rather, invited in with little to no proclivity of exclusionary tendencies. If spatial reconfiguration marks one form of practice designed to augment engagement within the confines of a gallery/museum, then the spectrum of viewers’ participatory potential elucidates the primary frame for how that structure becomes inhabited within the body. Shannon and company have asserted themselves within this theoretical framework, first devising and then producing an exhibition with the intent of demonstrating the mutable nature of space. In doing so, viewers excitingly emerge from the show perceptive to the vast disparity between what art spaces are and what they can be.

Not two separate worlds, but integrated homogeneity is the outcome. Spaces where these empathetic practices aren’t uncommon but, simply the standard. It might be better to state that the multiple areas of work are essentially stations for reflection, inquiry, and rest. And rarely do shows offer this to you—marking a world that allows you to find comfort in its perimeter. If what we are ultimately after in art is increased transparency, attentiveness, and engagement between a work and its intellectual underbelly, making the physical and discursive constructs of an area attuned to as many needs/desires as possible is perhaps the greatest pursuit we should strive for. In turn, spaces accommodatingly metamorphose into generative sites, eclipsing previous conceptions of partnership.

Yes, galleries/museums should certainly be asking: In service to whom? But there may just be a symbiotic respect between this question and its prerequisite query, in service to what? If the conjoint response merges to perfectly reflect a single outcome, then we have solved an ultimate tremor in the art world. At last, we see the emergence of a type of show that finalizes its point by allowing viewers unparalleled access to the totality and infinity of applicable resonances. So, while artworks in the show systematically contribute to the exhibition’s flexible and pliable education of access and accommodation, it is the discursive practices involved in creating this exhibition—both curatorial and administrative—that are resoundingly more persuasive. The art is the signalled augmentation, and the augmentation is the argument.

“Don’t mind if I do” is on view at Gallery 400 from September 23 through Decemeber 13, 2025. The exhibition was curated by Lauren Leving and Finnegan Shannon and includes artwork by Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, Pelenakeke Brown, Sky Cubacub, Emilie L. Gossiaux, Felicia Griffin, Ariella Granados, Joselia Rebekah Hughes, Jeff Kasper, Finnegan Shannon, Sandie Yi, agustine zegers.

About the author: Lucas Gómez-Doyle is an independent scholar, researcher, and art critic. His work broadly explores how the social geographies and political dynamics of public art, built environments, and architecture become activated by artists, citizens, and social movements. Animated by these interests, his attention is dedicated to how each respective category produces aesthetics and ontologies of civic participation that demand freedom, liberation, and self-determination. Guiding his recent scholarship, he draws extensively from his identity as a second-generation Mexican-American, focusing specifically on voices of Chicanx and Latine descent.