This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

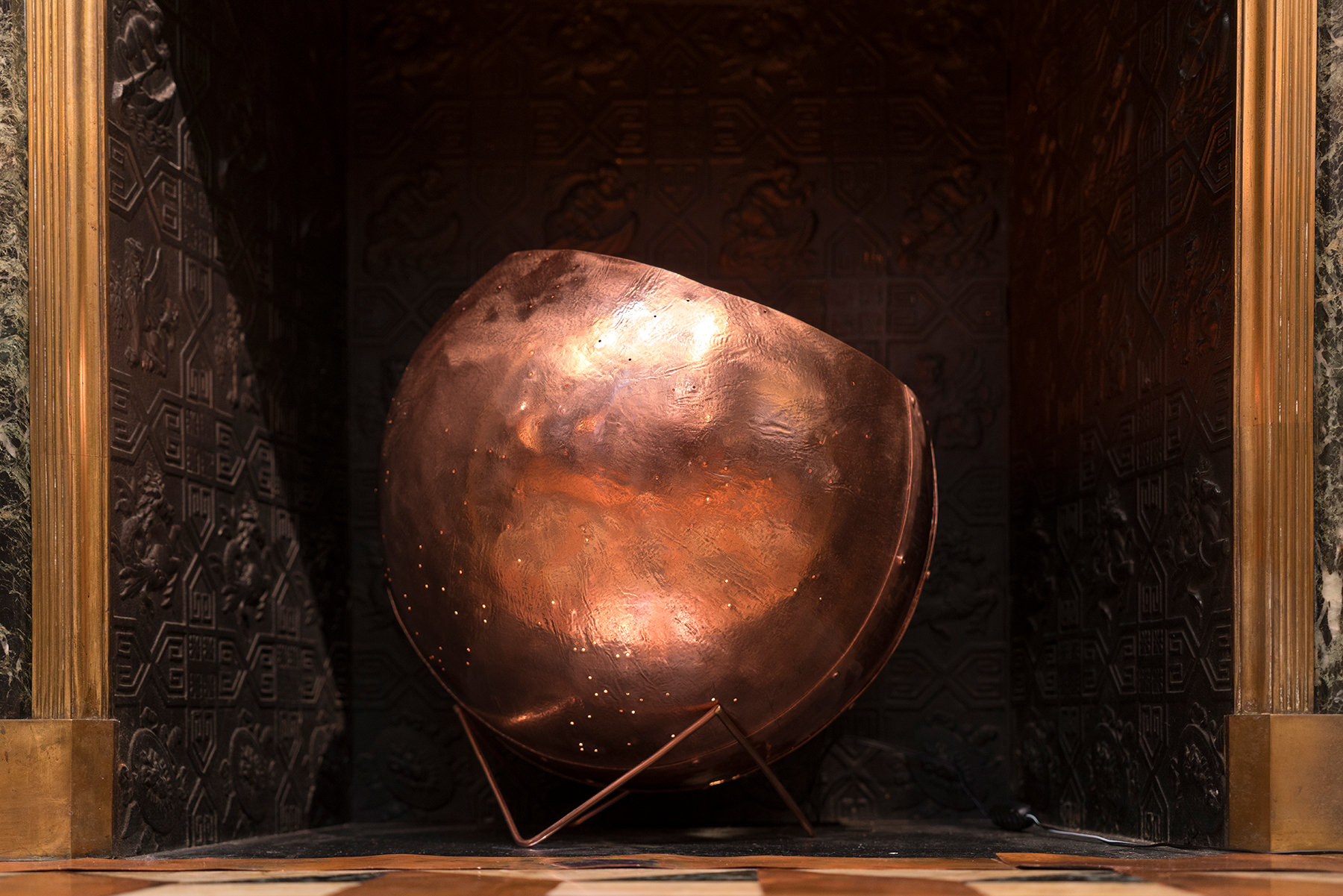

On the night of October 8, 1871, the constellation Orion hung low in the sky to the east, hovering over Lake Michigan. To the southwest, strong winds blew toward downtown Chicago, and Saturn, along with the stars of Sagittarius, would have been visible before sinking below the horizon later that night. Today, a map of this night sky perforates a luminous copper globe, a reimagined hod filled with copper-gilded coal nestled into the fireplace in the Library at the Nickerson Mansion, a lavish epitome of Gilded Age architecture and design, now the site of the Driehaus Museum. This copper and coal piece, Mercury’s Hearth: Coal, Electricity, Fire and Industry, is the contribution of Chicago-based artist Rebecca Beachy to the exhibition A Tale of Today: Materialities, currently on view at the Driehaus Museum. The exhibition is the fifth iteration of A Tale of Today, an initiative that activates and reconsiders the histories of the Gilded Age by bringing contemporary artists into the Museum’s historic space.

The map of the stars on the fateful night of the Great Chicago Fire is an ominous and essential point of departure for this ambitious exhibition by guest curator Dr. Giovanni Aloi. The devastation of the fire, claiming the lives of nearly 300 people and destroying over 18,000 buildings including the original residence of Samuel and Matilda Nickerson, is a pivotal moment in the emerging modern metropolis that Chicago would become. Twelve years later, on the site where their previous home had burned, the construction of the Nickerson Mansion was completed, an artistic and technological marvel hailed for its “fire-proof” design. Yet, Beachy’s celestial reference to the night of the Great Chicago Fire tells a different, more complex story, one that fortifies Aloi’s goal of Materialities: to take the viewers far away––temporally or geographically––outside the Nickerson Mansion in order to return to its interior with a heightened awareness of the materials and their charged histories. In this sense, the constellations in Beachy’s copper hod transport the viewer to consider concurrent haunting histories.1 Under the same night sky of October 8, 1871, about 250 miles north of Chicago, the Peshtigo Fire erupted in the northern woods of Wisconsin, tearing through the counties around Green Bay, consuming about 1.5 million acres of land, killing at least 1,200 people, and completely destroying the town of Peshtigo.2 That year, similar forest fires burned almost simultaneously all throughout the upper Midwest, leading the Chicago Tribune to refer to 1871 as the “Black Year.”3 In one calamitous night, both Chicago and the forests that provided the lumber to build it burned to ashes.

This cursed history was far from coincidental and had everything to do with the ecological disruptions caused by the Industrial Revolution and Chicago’s rapid growth in the late nineteenth century. New markets for lumber, grain, and livestock created complex, interdependent relationships between the city and its hinterlands, a history that is elaborately and eloquently laid out in William Cronon’s seminal text Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. As an environmental historian, Cronon’s thesis and moral imperative is akin to Aloi’s curatorial theme for Materialities: to unravel the paradox of modernity, making visible the intimate interconnections amongst different lands and materials which are too often obscured by our own cultural lenses and habits of consumption.

The framework of this exhibition gave artists the unique opportunity to engage with and respond to the materials and spaces of the Nickerson Mansion, tracing their ecologies and histories. Selected from an open call for proposals, Aloi assembled an impressive roster of 14 artists, all with ties to Chicago specifically or the Midwest more broadly. Spanning all three floors of the Driehaus Museum, the exhibition is divided into loose chapters, addressing resource extraction, gender and social structures, conceptions of home, and unrecoverable histories.

On the first floor, three artists––Rebecca Beachy, Olivia Block, and Jonas N.T. Becker––examine the idea of nature as resource, with distinct approaches to their chosen rooms of the mansion. Within the Library, a room finished with ebonized wood, high bookshelves, and a statue of Mercury in the corner, Beachy considered coal and copper to be the essential materials of choice: coal as an archive of plant bodies, and copper as the conduit of electricity, one of the marvels of the Gilded Age. Using the fireplace as a frame within the room––one of ten fireplaces within the mansion which actually never contained an open flame––Beachy forged multiple material and personal histories into her installation, including the copper hod with glowing coal, copper overlays on the hearth’s geometric pattern, and delicate copper cones tucked into the bookshelves. In an interview, Beachy noted that she wanted to explore her personal connection to the history of extraction; her great-great-grandfather began his life as a miner in Scotland, before immigrating to the United States and walking hundreds of miles underground as a coal mine inspector in Ohio.

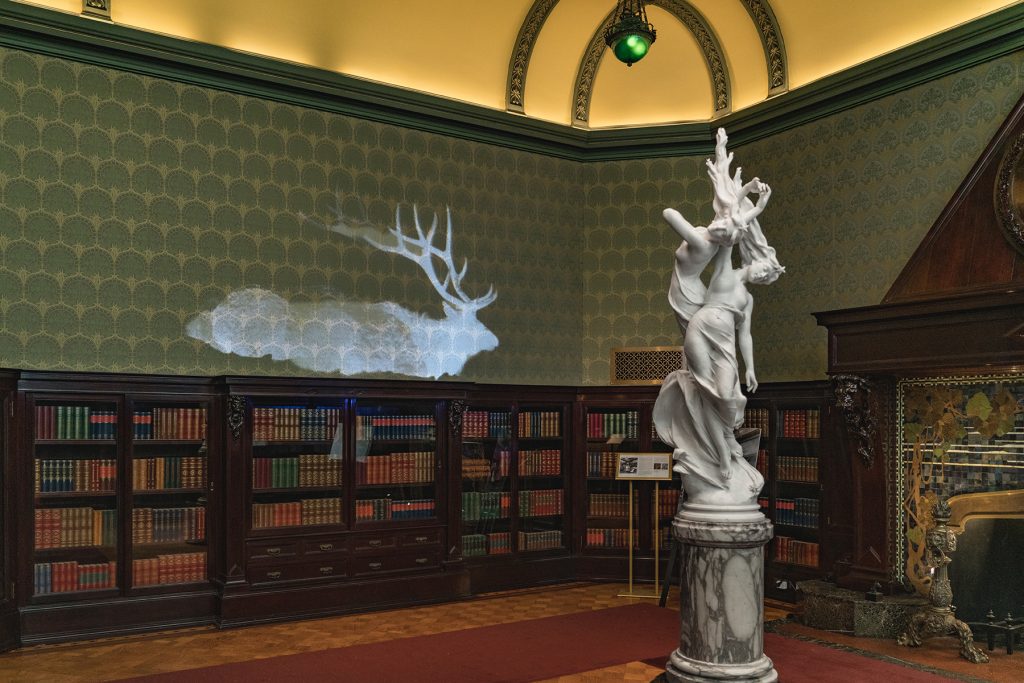

In the Maher Gallery, Olivia Block brought the sounds of a forest and eerie projections of wildlife including elk and bears into a space which was once filled with numerous taxidermy mounts. While the Gallery originally served as a space to display the Nickerson family’s vast art collection, the second owner of the mansion, Lucius G. Fisher, was an avid hunter, and he renovated the room to accommodate his animal trophies. Block was likely inspired by an archival photograph from this time period showing the ghastly size of Fisher’s taxidermy collection. Her ingenious intervention, utilizing the archives of Yellowstone National Park, brings the memories of these animals back to the walls of the mansion in ghostly forms.

Jonas N.T. Becker brings the idea of extraction to the Dining Room, placing a partially processed slab of timbered walnut to the table. In its suspension between a natural and commodified state, it’s hard not to see this wood morph into other forms, like a large tenderloin steak or stratified rock. Tucked within the room’s display cabinets, alongside traditional silverware, Becker placed pieces of raw oak, coal, and small figurines carved from coal, to further underscore the extracted natural resources and industries that made the growth of Chicago possible. This is an understated response to the decadence of the elaborately carved oak and walnut interior of the Dining Room, a room which, as Aloi poignantly stated during a tour, is haunted by the ghosts of many, many trees.

Rounding out the first floor, Ebony G. Patterson and Jefferson Pinder foreground the sociality of the Nickerson Mansion, subtly interrogating the access––or denial of access––that someone would have encountered as a visitor. In the Smoking Room, Pinder’s sculptural sound piece Gust seemingly bursts out from the fireplace, sending emanations of nineteenth-century voices into the space. In a room where male guests would have gathered after dinner to socialize, Pinder’s collage of sound selections provide a subversive context; the voice of George W. Johnson, the first African American recording artist, singing “The Laughing Song” invokes a history of racialized entertainment of the era. Similarly, the stark contrast of the pale blue Moorish ceramic tiles in the Smoking Room juxtaposed with the salvaged tin tiles from demolished houses that Pinder used to construct the audio sculpture call to attention the separations of class that existed in the nineteenth century and persist today.

In the bedrooms on the second floor, Laleh Motlagh, Edra Soto, and Dakota Mace address the conceptions of making a home, exploring how the migration of materials and design carries not only a material element but also a cultural identity that navigates liminal spaces. In Threaded Memories, Laleh Motlagh constructed a sublime rendition of a Persian rug, an ingenious summoning of the rug that was once central to Adelaide’s bedroom during the Fisher family’s residence. Made of clear acrylic and dried leaves from outside the Driehaus Museum and from her father’s garden in Iran, this “carpet” hovers above the floor, casting the shadows of its intricate pattern onto the surface below, replicating the layers of cross-cultural identity. Through sensitive use of materials and pattern, Motlagh brings attention to the cultural memory that is so often intertwined with material production. More specifically, Motlagh’s floating rug foregrounds an acute tension: the translation of culturally specific designs and modes of production––like a Persian rug––into an object of status and luxury, oceans away from their origins. It is an appropriation that simultaneously admires and forgets the significance of craft as cultural knowledge, turning it into a commodity, just like lumber or coal. In her creation, Motlagh reclaims this symbol of cultural heritage from her homeland.

In her installation Dáda’ak’ehgo Litso (there are yellow fields all around), Dakota Mace brings nature in its elemental form into the museum, using natural dyes and organic photographic processes to activate the bedroom which belonged to Mrs. Nickerson. Responding to the floral pattern in the walls and carved wood, Mace created eco-prints using eucalyptus, draping the room with delicate veils of yellow. Her round abstractions of Diné designs traditionally found in weavings are in fact anthotypes, dyed using Osage orange and marigold. Recalling her conversations with Aloi about the theme of Materialities, Mace said she began to think of nature as being trapped in the museum, and wanting to bring the materials and representations of nature found in the mansion back to life, allowing them to breathe again.4

The motifs found in the works by Mace and Soto, while significant to their Diné and Puerto Rican cultures respectively, can be traced to designs found in northern Africa. By emphasizing the diasporic nature of design, Motlagh, Soto, and Mace take the viewer far outside the walls of the Driehaus Museum, revealing the ecological networks and systems of exchange which informed every floral pattern, every bit of tile, every embellishment which added to the warmth and verve of the home.

Furthering the connection to the Great Chicago Fire and material explorations of electricity, sculptures by Richard Hunt and Luftwerk anchor the other bedrooms. One of the greatest African American sculptors of his time, Hunt joined the roster of artists for Materialities before his passing in December 2023. His posthumous contribution Divided Growth resembles a phoenix, a charged motif that symbolizes the rebirth and resilience of African Americans after emancipation. Put into conversation with the Japanese bronze urns nearby, also featuring a phoenix, his welded steel sculpture can be read as a reflection of his hometown’s resilience and rebirth, as well.

Luftwerk, the ever-imaginative duo of Petra Bachmeier and Sean Gallero, are known for their explorations of the ephemeral qualities of light and color. In the Nickerson Mansion, they found inspiration in the abundance of Edison bulbs, arranged in the ornate ceilings and along the cornice of the second floor. Konstellation is a transfixing copper sculpture that mimics those fixtures, with gently pulsing bulbs that conjure a vital rhythm to the magic of electricity and its connection to our own human body. Similar to Beachy’s copper globe, Luftwerk’s contribution extends our understanding of copper’s materiality, picturing the universe itself as the progenitor of electrical energy.

On the third floor, Barbara Cooper and Industry of the Ordinary conclude the exhibition by evoking histories that cannot be recovered or refuse to be told. In Palimpsest, the duo of Industry of the Ordinary constructed a replica of one of the Mansion’s doorknobs using clay from the Chicago River. Its quiet affect is deceiving; Palimpsest monumentalizes the labor that occurred in the aftermath of the Chicago Fire, when builders urgently sought fire-proof materials for new constructions, going so far as the depths of the city’s river to extract clay. Beneath the extravagant layers of marble and wainscoting, humble bricks of clay remain a foundation of the mansion and evidence of that pivotal moment of Chicago history.

The materials of the Nickerson Mansion belong to complex ecosystems of nature and culture, but they have also been witnesses for nearly 150 years, carrying memories that cannot so easily be retrieved. Barbara Cooper’s sculptural and unreadable books at the end of the exhibition reiterate this; even through the material explorations done by these artists, the house has stories and secrets that remain elusive.

By investigating materials of the Nickerson Mansion and letting those histories lead the way, the artists of Materialities conjure apparitions of nature in its rawest and most potent form. What the artists vividly demonstrate is that the Driehaus Museum is indeed haunted––not by the people who lived there or the servants who worked there, but by the echoes of nature embedded in every room and by the emanations of delicate relationships between nature, cultures, distant stars and faraway lands––all the elements that generated our modern way of life.

A Tale of Today: Materialities, curated by Dr. Giovanni Aloi, is on view at the Driehaus Museum through April 27, 2025. The exhibition includes works from artists Rebecca Beachy, Jonas Becker, Olivia Block, Barbara Cooper, Richard Hunt, Industry of the Ordinary, Beth Lipman, Luftwerk, Dakota Mace, Bobbi Meier, Laleh Motlagh, Ebony G. Patterson, Jefferson Pinder, and Edra Soto. The show is presented as part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaborative initiative organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The exhibition is among more than 35 Art Design Chicago exhibitions that highlight Chicago’s unique artistic heritage and creative communities.

Footnotes

- In an interview with the artist at her studio, Rebecca Beachy pointed out this occurrence of simultaneous fires and the looming presence of the Great Chicago Fire as “the talisman of the house.” The associations drawn from her study of astrology and the exploration of electrical energy provided a resonant context to consider for analyzing this exhibition. I extend my gratitude to Rebecca for generously sharing her research process. ↩︎

- “Peshtigo Fire,” Wisconsin Historical Society, August 3, 2012, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1750. ↩︎

- Stephen J. Pyne, Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire, Pbk. ed, Cycle of Fire (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 230. ↩︎

- In a wide-ranging interview in her Madison studio before the exhibition’s installation, Dakota Mace shared the research and processes that informed her pieces for Materialities. I extend my thanks to Dakota for generously speaking about her practice and these works. ↩︎

About the Author: Kristie Kahns works in the photographic field as an educator, image-maker, writer, and independent researcher, based in Chicago. Her interests include contemporary approaches to photographic materiality, and the pedagogy of analogue and historical processes. She is a recipient of the 2025 Elaine Ling Research Fellowship from The Image Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University. She received an MA in Arts Administration and Policy from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and holds a BA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago.