This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

Throughout time, there have been countless trends, styles and jargon birthed, and then bastardized from their Chicago lineage. Our fixation last year with being ‘very demure, very mindful’ (popularized by Chicago-based TikTok creator Jools Lebron) is an obvious example. Or, why everyone’s eyebrows had to be on ‘fleek’ in 2014. So it’s not entirely shocking that 86-year-old artist and Chicagoan Robert Earl Paige identifies as a ‘ghost artist’ because he is rarely credited for his influence on culture. Perhaps being an artist in Chicago and being uncredited are synonymous. Perhaps artists are still paying the karmic debt of a predecessor. Perhaps going largely uncredited and unrecognized is what we all deserve.

Nowadays audiences seem to believe they’re most equipped to discern when an artist or cultural contributor is overdue—deserving of recognition and praise by the masses. Oftentimes, these observations are endearing bids for justice on behalf of the unsung. Robert Earl Paige seems unaffected by such recognition or praise.

In April of 2024, The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige debuted at the Hyde Park Art Center (HPAC). This is one of, if not the longest running show at HPAC. When I arrived in HPAC’s main gallery, it became evident why the institution would make such a significant investment in surveying Paige’s work.

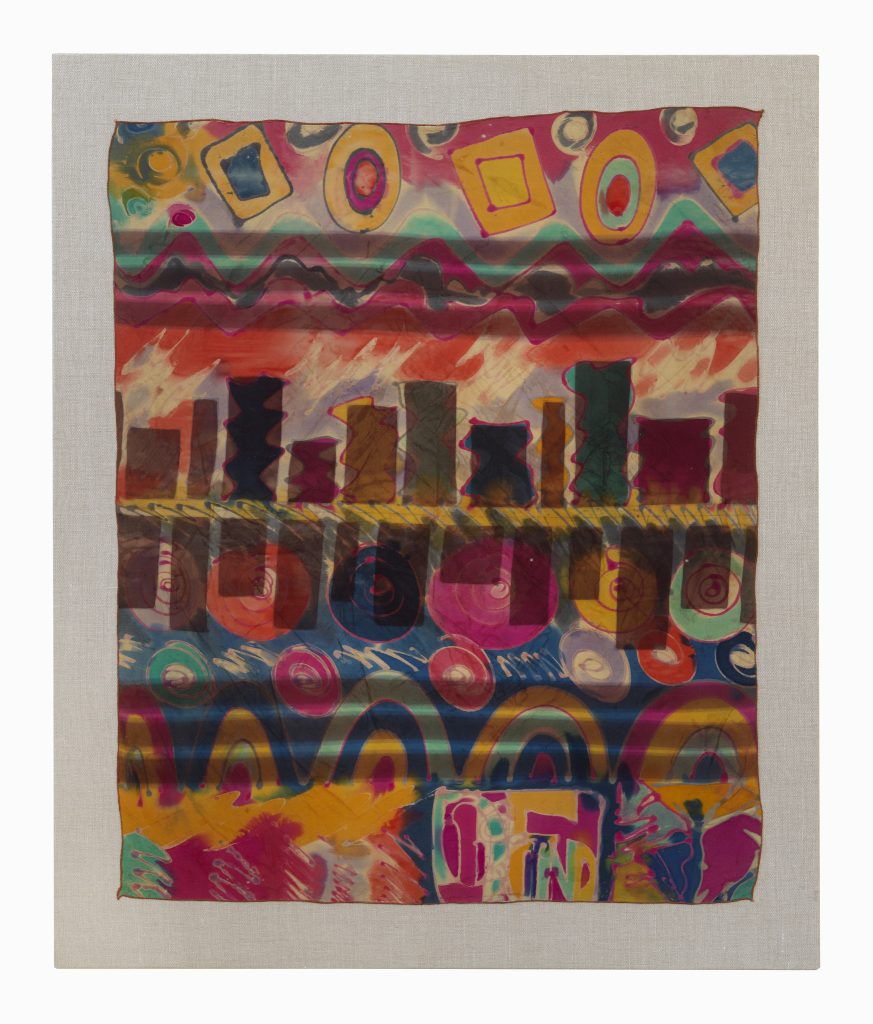

Robert Earl Paige is a painter, ceramicist, printmaker, collagist, pattern maker, and textile designer. Patterns and colors ground his multidisciplinary practice and this show. A mural painted by Dorian Sylvain and modeled after a pattern designed by Robert Earl Paige covers the entire west wall of the show. The creative decision to display art on non-white walls highlights Paige’s vibrant work and also how cherished he is by his community.

Curator Allison Peters Quinn successfully surveyed 60 years worth of work from Paige by drawing attention to his devotion to color and patterns that serve as a throughline to Paige’s many eras and mediums. Many Chicagoans know only bits of the lore surrounding Paige and his contributions to the Chicago arts scene, as well as his contributions to the national domestic market: He designed domestic textiles that were carried in Sears and Roebuck; he spent time designing textiles and patterns in Milan; and he was a teaching artist for After School Matters—a summer arts program for teens founded in 1991 and expanded in 1995 through a partnership between Chicago Public Schools and Gallery 37. After School Matters is still active and continues to change the trajectory of artists in Chicago, including many of my close friends.

Paige’s work has garnered more attention recently with an exhibition curated by Duro Olowu at Salon 94 in New York, the aforementioned HPAC exhibition, and the upcoming Give the Drummer Some—an installation for the Smart Museum’s 50th Anniversary that closes this July. Despite this busy schedule of professional obligations, Paige regularly visits his show at HPAC, interacting with guests and having his photo taken by admirers. It’s an opportunity to showcase the way he styles himself. The way Paige mixes colors and patterns doesn’t reside solely in his artwork. His style leaves many in awe. Grounded by bold eyewear, Robert stands out in the crowd. He’s tall and colorful, adorned with beautiful silver bracelets and rings.

I initially sought Robert out for an interview to discuss three elements integral to his show—community, style and glamour—but we kept missing each other. Instead, I’ll use those three pillars to speculate and respond to his show.

On Community

Robert Earl Paige was born in and currently lives in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood, and throughout his career has participated in countless community initiatives, many through the Black Arts movement. I’m curious to understand how Paige found his community, connecting with artists, makers, thinkers, and concerned citizens, and how they dealt with conflict without engaging in public shaming campaigns like the ones we regularly scroll past on the internet.

The Art industry regularly disavows it’s capitalistic nature by rebranding as an amorphic, innate world where art shows produce themselves—objects are supernaturally fabricated for large-scale installations; videos are mysteriously funded, filmed, edited and color-corrected in the nick of time for the big screenings; and galleries solidify their relevance by uplifting budding talent from within the neighborhoods they occupy. Most artists of any marginalized identity understand how much more complicated it is to feel authentically recognized, respected, and cared for in and by large Art institutions. Or, have to grapple with an institution’s racist, imperialistic legacy while simultaneously rising to the merit-based juncture of debuting a show that can and often will thrust them further into the spotlight, further from their communities that helped lick their wounds after countless false starts and the unprofessional, unethical, and unfair gallery practices. The spotlight can make artists more vulnerable than they were before acclaim, when they were unrecognized and institutionally undesirable; unsung.

In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel R. Delany describes an encounter at an art opening between a clique of artists, a conversation between an artist showing at a nearby gallery and an art critic. Another artist who witnesses this exchange becomes agitated. They oversimplify the interaction—accusing the other artist of dictating the outcome of the review and reducing his “friend’s” achievement as networking: “You know, today in the art world, it’s all about who you know, who you meet, who you network with…” Delany includes this encounter to highlight the inconspicuous unit responsible for the persistent social dissonance many of us find ourselves in time and time again: misconstruing networks for communities.

Networking is essential to being a successful artist. But knowing and revering the different responsibilities one has to their community and to their networks can be life-affirming. Community rallies around causes, creates mutual aid campaigns, pays people fairly and in a timely manner. Networks are more passive, less invested in wellness, and are voyeuristic in nature. Networks are focused on achievements and proximity to celebrity. The volume of networks are high when there are accolades and celebrations. Very rarely are networks active during public breakdowns, bids for mutual aid, or need for material support.

Despite how easily artists can misconstrue networks for community, Paige’s show crystalizes his understanding of how community has played a pivotal role in his multifaceted practice. The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige features an installation around the perimeter of the room featuring longtime friends and collaborators Lori Bartman, Matty DeVita, Espi Frazier, Malika Jackson, Terah Jené, Turtel Onli, Brian Parris, Tony Smith, Dorian Sylvain, and Bernard Williams. Many of these artists like Tony Smith and Malika Jackson have worked closely with and presented work at the Hyde Park Art Center for years. Other artists like Dorian Sylvain and Bernard Williams have visible artworks decorated throughout the Southside. Titled “Parapluie” (the French word for “umbrella”), the installation aims to erase boundaries between decorative and fine art, to expand the range of artists and art represented in the institution.

The artists and work included in “Parapluie” were selected by Paige, demonstrating another essential aspect to working in community: imbuing value into those around you and what they do. In community, everyone’s a maker and everyone adds unique value. Removing the capital ‘A’ in art makes it possible for everyone’s work to be admired and experienced. Removing the capital ‘A’ makes everyday life an artistic experience. How wonderful it is to think about everyday Black life being recognized as art not just because those of us living it declare it to be, because our community also recognizes it as art.

There’s a way Black Chicagoans speak with one another that’s so casual and unique. It’s so everyday that someone in passing could easily write it off as inconsequential. What can be overlooked are the inflections of the Great Migration traveling from our tongues back into the Midwestern air. The southern twang—most likely from Mississippi—might slowly evaporate but the slang remains!

Paige’s work champions those everyday moments that brighten up our days while we wait for delayed CTA buses, the city to fill potholes, our number to be called in Harold’s, to merge onto Lake Shore Drive, the next Chicago Summer. Paige’s work champions the patterns of everyday Black life: street lines, street signs, policy numbers, cottage grove, neon signs, kitchen tiles, bespoke suits for church, patent leather mary janes, hair barrettes, bonnets, beauty supply store aisles, chicken wings, mild sauce, hot sauce, salt, pepper, white bread for the bones, music notes, the shape of jazz-improv, free, disobedient, vigorous and a tinge of wanderlust.

The shapes, colors, patterns within Paige’s work aren’t new but they’re precious. The patterns Paige constructs throughout all his work may even be familiar to some and I’d argue that’s what makes them so dynamic. These patterns can be looked at as an invitation to stop and be present within the moment—to look at your immediate surroundings for inspiration. There’s vibrant color, rhythm, and patterns nesting within the mundane everyday Chicago Southside life.

The late bell hooks wrote, “Communities sustain life—not nuclear families or the “couple” and, certainly not the rugged individualist…” the status of hierarchical power in traditional “loving” relationship dynamics such as the nuclear family or romantic partnership is named and challenged by hooks. In community, there’s nuances to power dynamics. Sometimes, the elders with the vital wisdom aren’t the oldest community members. And, sometimes love among community members isn’t tender. I first witnessed a bit of this at work when I introduced my then teen students to Robert Earl Paige while he was a resident artist at the Hyde Park Art Center.

Paige led a workshop, encouraging my students to think critically about language, symbols, color, and intention. He introduced us to Adinkra symbols, explaining their significance and influence on contemporary culture today. The way he armed us with this information then empowered us to do what we willed with it indicated to me that he wasn’t interested in lording over us with how much more he knew. He spoke to us all as equals, he joked with us, and told us stories from many moons ago. The students took plenty away from our time with him. Guests had similar access to Paige while his show was up. And whether or not they were aware of facts like Paige and Dr. Carol Adams founded the first ever Black arts festival at the SouthSide Cultural Center in 1976 or his early membership in AFRICOBRA, it wasn’t uncommon for visitors to be able to commune with Paige as they colored in print-out patterns of Paige’s made available in a gazebo in the middle of the gallery. There would sometimes be kids, teens, and elders at the table coloring together, talking as jazz played in the background.

Communities teach each other how to authentically trust, love, and communicate with one another. Perfection doesn’t thrive because oftentimes, community is a continuum of many messes. Everything our nuclear families denied us of in our adolescence, our institutions deemed unworthy, our romantic partners disregarded are addressed and reckoned within the communities we occupy and invest in.

On Glamour

“Do you know where you’re going to? Do you like the things life is showing you?” sings Diana Ross in the theme song of the 1975 film Mahogany. Mahogany is the story of a disgruntled fashion student in Chicago who gets her big break as a fashion designer and model in Rome. The film depicts Chicago’s South Side as destitute—Black folks living in densely populated conditions, advocating to their local politicians to no avail, dodging crime, evading police brutality, and struggling to make ends meet, which doesn’t include fashion.

What should an artist do when they can’t creatively evolve in their hometown? They leave. At least that’s what Mahogany and Robert Earl Paige did. It’s unclear if Paige felt he had no choice other than to leave the United States and move to Milan. And it’s even more unclear how Paige acclimated to the Italian culture, if he found it difficult or generative. Perhaps guests of Paige’s show can infer what his acclimation process was by looking at his artwork. Perhaps it was vigorous, playfully disruptive, imperfectly geometric, iterative and curious.

Mahogany acclimates poorly, professional demands causing her to lose perspective on her personhood, her support network, her artistic drive, her dreams. Colleagues and a love interest deter her away from why she left Chicago. In this instance, glamour distorts Mahogany’s sense of autonomy, rendering her vulnerable to egotistical men who see her as nothing more than an entity to be possessed—a sex object. The film takes shallow dives at rendering the sociopolitical landscape of the city she left without a second thought.

It takes effort to become glamorous. To become more fabulous, you must become less relatable and vulnerable, you must wear a mask. Who taught Paige how to dress? What sort of rituals does Paige perform before stepping out into the world? How did he learn about glamour? Did it ever occur to him that design is at the core of being glamorous?

The fashion industry moves notoriously fast—too fast. The industry moves so fast that its workers, cultural phenomena, histories, and techniques are neutralized from the workspace season after season. More interns, more free labor, more moodboards, more culture, more models, more stars to be shoved into the hypermarket; perhaps people buy things to cover up their anxiety and uncertainty about who is truly fit to run this country, if peace can indeed exist in the Middle East, or if America was ever really as great as they made it out to be. Why think critically when there’s fur, fragrances, gold, diamonds, paintings, sculptures, silk, and leather to indulge in.

There’s ineffable pleasure in acquiring things. And within that pleasure, whether it’s sex, drugs, food, money, clothes, is an impulse to relate to the material world. This impulse can be simultaneously life-affirming and threatening. Race, class, and gender determine how glamour is perceived by onlookers. Cut to the montage in Mahogany of Diana Ross posing in various fashions, furs, and wigs only to become unrecognizable to herself. “The things we buy to cover up what’s inside” raps Kanye West in his seminal “All Falls Down” sometime before he lets us all down.

From the outside looking in, Chicago is often overlooked as a site for fashion to thrive within. However, Chicago has a veiled history and relationship to fashion. It’s in the name of Nat King Cole, Michelle Obama, Twista, Quincy Jones, Jody Watley, LisaRaye McCoy, Donny Hathaway, Bernie Mac, Kid Sister, Law Roach, Chaka Khan, Shaun J. Wright, Lil Hardin Armstrong, Da Brat, Sam Cooke, Edward Jones, and Honey Dijon. It’s the late Andre Leon Talley’s early tenure at EBONY magazine uplifting unsung Black models, designers, and artists of that time—and his friendship with Eunice Johnson, who he sourced clothes for, traveling to Paris on her behalf.

In his memoir The Chiffon Trenches, Talley describes an incident at a dinner party in Paris where people insulted him, referring to him as a monkey in French. They assumed he didn’t know the language. This incident made me wonder what sort of things Robert Earl Paige encountered during his time in Italy. How did he prepare for the stark cultural differences? Did he speak the language? When did he ever feel safe to unfasten his personhood while abroad? There’s countless Reddit articles, Youtube series, and other social media accounts that tackle the concerns and harsh realities of traveling while Black. This content may be well intentioned but it doesn’t necessarily empower Black people to experience the world, to take risks. Many people use social media to explore and build insight from the comfort of their living room. Such tools weren’t available to Mahogany as she was the first in her family to venture out. I assume the same could be said for Robert Earl Paige. Yet both ventured abroad to chase their dreams of being artists.

The fashion industry has pathologically excluded Black consumers from fully participating in the industry by exploiting the lack of representation. This means the likelihood of culturally insensitive, fatphobic, antiblackness, and transphobic ideas being disseminated through a collection are high. Paige’s show at HPAC is unequivocally Black although there aren’t many legible Black human figures present within the exhibition beyond a selection of archival images of Robert Earl Paige throughout the years.

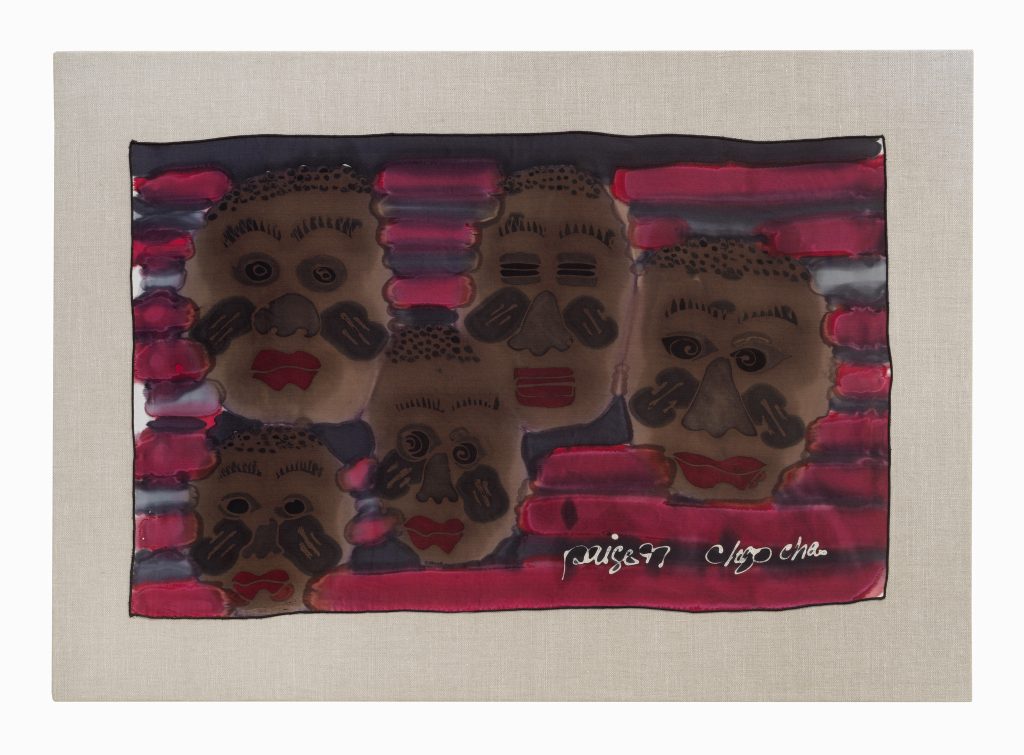

Clues of Paige’s cultural reference points and devotion to culture can be found in the titles of his work throughout the show such as In Reverence to the Ancestors, a hand-painted and -dyed work on crepe de chine silk which consist of bold patterns made in black, white, and red inspired by Adinkra symbols from 1997. Or Power to the People Series, a hand-painted stoneware work that depicts three wide-eyed faces adorned with geometric patterned hoods (reminiscent of baskets and textiles presumably inspired by Paige’s time spent researching the Ndebele people of South Africa) that directly address the viewer as the title directly references style icon and civil rights activist, James Brown. Academics might insist Paige’s work references solely European artists and designers like Wassily Kandinsky, Anni Albers, Emilio Pucci, and Missoni; although he’s quite vocal about being inspired by West and South African patterns and symbols. This synergy between European and African influences creates warm and inviting tones that promote justice and social progression.

Fashion thrives off controversy even if it’s at the expense of those already vulnerable, trying to get their foot in the door. And subsequently it also means that we as Black consumers are satisfied with the bare minimum when they are included i.e Black models, or creative director of a coveted fashion house. I don’t think this sentiment applies to Paige’s commercial design work for Sears and Roebuck because of how scarce opportunities were for Black artists to insert their pride and culture into a product with national distribution. The intention was clear: “bring freedom of choice to the marketplace”.

On Style

“Fashions fade, style is eternal” – Yves Saint Laurent

Chicago is often overlooked when it pertains to style. Chicagoans are not devoid of style. Their style simply isn’t contingent on projecting elegance and luxury. There’s a commitment to the mundane—the day-to-day utilitarian sensibility. Style can be oppressive and violent because it has the power to reify what’s consumable or marketable, which limits how people imagine themselves in clothes, where and why. Style becomes less playful when it must sell or become broadly adopted. How does one style themselves for the end of the world as we know it?

Playwright and dear friend Amanda Horowitz exposed me to Antonin Artaud’s The Theater and Its Double when I commissioned her for a project in 2016. Horowitz shared Artaud’s idea that “the universal collapse of life at the root of our present day demoralization—culture made to tyrannize life—deprives cultural ideas of their real magic and living power.” This inspired Amanda to reconsider style “as a defiant medium with magical potential, prompting living theater that does not discern itself from the culture it sustains,” which suggests that style, the act of getting dressed and dressing up, doesn’t have to be reserved for sacred occasions or purposes. Style has the power to resist the mundane, raise awareness, and confront creative hegemony. It’s equally as important to style one’s self for a dinner downtown as it is to wait for the Garfield bus to then transfer to the Green Line. This naturally makes me think of the way Robert Earl Paige styles himself and his work.

Upon entering Paige’s show at the Hyde Park Art Center, guests are immediately confronted by style—Robert’s style. A red, black, navy hand painted and dyed piece on crepe de chine silk reads “1 of a Kind” on the northernmost wall of the gallery, functioning like a synopsis for the show; Robert Earl Paige certainly is one of a kind. Curation in a gallery context is like a cousin to styling in most contexts. Both help viewers process visual language, themes, and motifs. They explain how to read the story, and what to take away.

The styling decisions Allison Peters Quinn, Robert Earl Paige, and fabricators made aim to highlight and uplift Paige’s sophisticated yet playful synchronized artistic temperament. Nothing within the show is more important than any other work. Robert’s painted silks are framed and installed across muraled gallery walls next to commercial examples of his design work for Sears, or a staged living room environment highlighting a rug patterned after his design. The silk work is as precious as the rug installed on the gallery floor. The ceramics couldn’t have happened without the drawings. And the jazz playing throughout the gallery reminds us that this work flies free.

Both fashion and style seem to be official responsibilities of our coastal sisters. That’s not to say that Chicagoans don’t care about style, dress with the intention to express themselves or that it’s a practice only uplifted by the youth. We have our elders at the window seats of the CTA, with their giant Ted Lapidus sunglasses and vintage Gucci monogram crossbody bags. We have our fly girls with the silky 40” of Brazilian hair, Yeezy pods and ripped True Religion jeans. We have our old heads with vintage Pelle Pelle embossed leather jackets, vintage Bulls gear, Carhartt work suits, beef and broccoli Timberland boots. We have our uncles donned in diamonds with yellow gold settings, leather baseball caps, linen sets during the summer months while overseeing the barbecue and Stacey Adams snakeskin derbies and mules reminiscent of the shoes sent down Martine Rose’s runways the past few seasons.

The epicenter of style is not the Gold Coast, West Loop, Andersonville, or Lakeview. Style thrives and evolves out of South Shore, Austin, McKinley Park, Kenwood, Garfield Park, and Woodlawn. Black Chicago is the epicenter of style for the city and the world. There’s countless examples of Black Chicago inspiring the world with the way we style (and, create) trends like, fleek eyebrows (Peaches Monroe) or cutesy, ‘demure’ (Jools Lebron) dispositions to oppression and marginal fame. It’s evident in the way Paige styles himself and his work. In the words of Horowitz, “style is the starting point for the creation of visual language—the looks correlate with whatever art…it is a fashioning of the self in real time, a declaration of the possible.”

Chicago may not have direct access to the sample sales, runway shows, or flagship stores but our style declares what’s possible through our imagination and through our city.

Outro

Style and glamour are two variables that aren’t often associated with Chicago’s expansive ethos because there’s an absence of the fashion industry here. But we don’t lack community. I’m not sure that these three variables have the power to completely notate the reverence Chicago has when it comes to world building through art but it’s fun to think about! Robert Earl Paige has inspired me to deepen my relationship with my own personal style so that I can unfasten any and all creative buckles that stop my creative process from flowing smoothly out and into whatever medium I see fit. This city may be plagued with segregation but that doesn’t mean that our creative practices have to obey the same dynamics of city design. And if this city ever begins to feel too small or suffocating then we can always leave. Because Chicago will be here for those of us that have put our time, our hearts, love, and devotion into it.

* * *

The United Colors of Robert Earl Paige was on view at Hyde Park Art Center April 6 – October 27, 2024. The show was presented as part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaborative initiative organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The exhibition is among more than 35 Art Design Chicago exhibitions that highlight Chicago’s unique artistic heritage and creative communities.

About the author: Jared Brown is an interdisciplinary artist born in Chicago. In past work, Jared broadcasted audio and text based work through the radio (CENTRAL AIR RADIO, 88.5 FM), in live DJ sets, and on social media. They consider themselves a data thief, understanding this role from John Akomfrah’s description of the data thief as a figure that does not belong to the past or present. As a data thief, Jared Brown makes archeological digs for fragments of Black American subculture, history and technology. Jared repurposes these fragments in audio, performance, text, and video to investigate the relationship between history and digital, immaterial space. They have published writing in Sixty Inches from Center, CULT CLASSIC Magazine, the Chicago Reader, Press Press and Tru Laurels. Jared Brown holds a BFA in video from the Maryland Institute College of Art and moved back to Chicago in 2016 in order to make and share work that directly relates to their personal history.