Diana Solís’ and Patric McCoy’s photographs contain and unveil static. The electrons and protons dance among their journalistic and artistic secrets—the documentarians pinpoint specific subjects that are sometimes familiar apparitions. As if I scoot scrappy socks across an eighties carpet, I feel the friction between knowing and not knowing, where surreptitious shocks evoke queer longing, nostalgia, and futurity. The friction is the dissonance—a lot of the referenced queer spaces I am unaware of, are closed, and enmeshed by history. The currently-on-view exhibition at Chicago Art Department, Just Below the Surface curated by Carlos Flores and Cristobal Alday, counters the erasure of the memories of queer1 people of color.

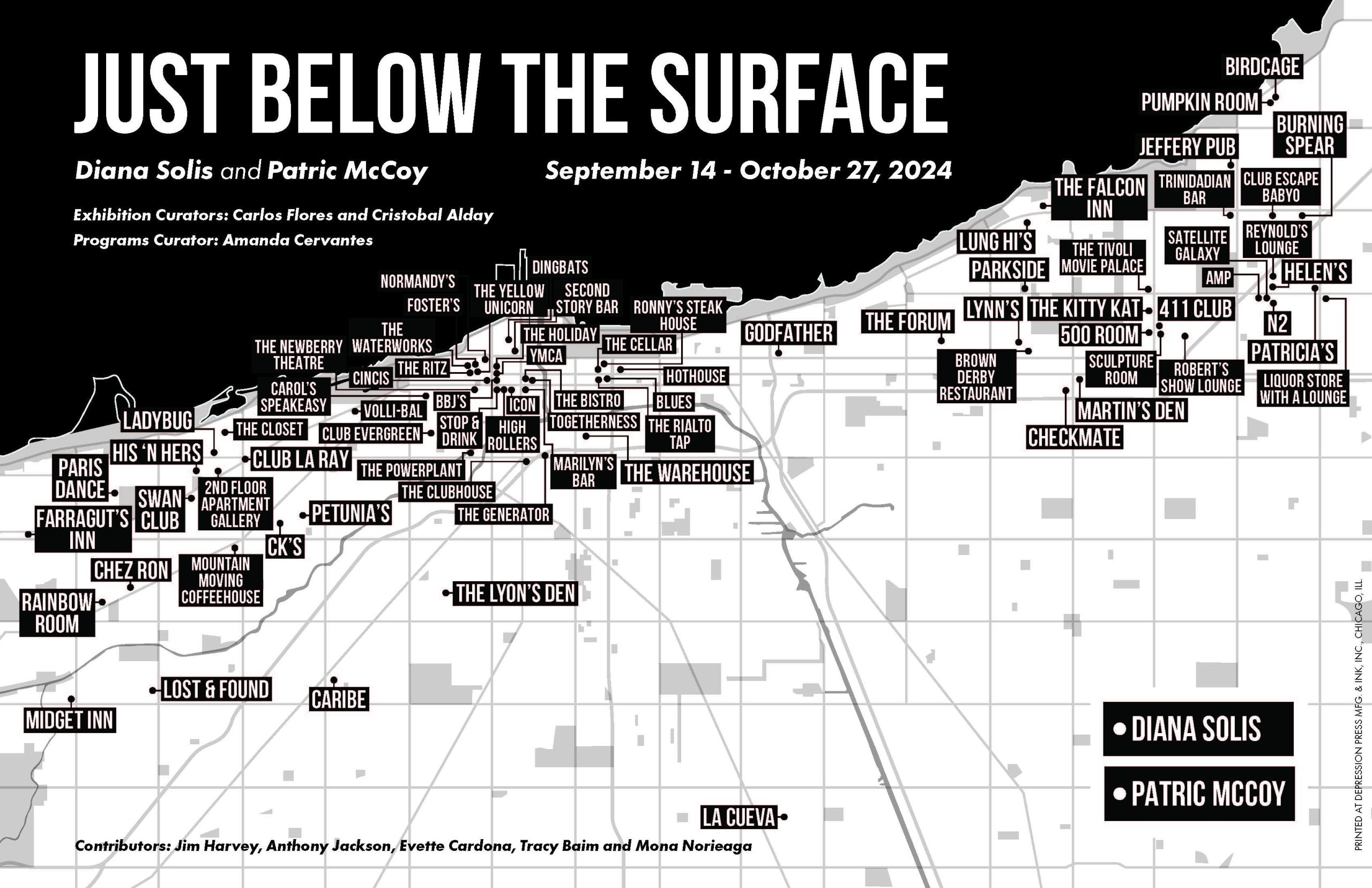

When encountering the provisional archival space, a huge map on the wall showcases a crisscrossed landscape. At a deeper glance, I can make out that it’s Chicago. Lake Michigan and the Loop are recognizable but turned sideways. Hand-written and printed pins delineating queer spaces of the night, past and present coalesce endlessly. Viewers can add map markers. The map is a subversion—creating equitable map-making when Chicago is infamously divided into the North and South sides. I put up a pin (Dugan’s Bistro) among the original listed landmarks (Petunia’s, CK’s, and La Cueva) and handwritten ones (Jackhammer, The Marshfield Courts, and Manhandler Saloon).

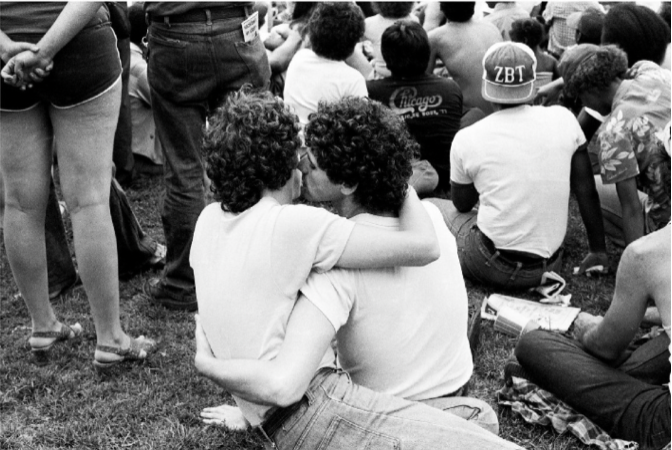

Left adjacent to the map is Solís’s photograph, Couple at Gay Pride Rally (no date marked), capturing two male-presenting individuals embracing—their faces obscure into each other’s curves. One’s lips seem to long for the other’s ear; perhaps sharing a lover’s secret. To the right of the map, McCoy’s Harper Court Chess Players (1985) appears as a static moment of respite: two men languorously playing chess in a park. The curators nestled sets of headphones next to each of these black-and-white prints, one playing a mapping session (what the curators call the archival process of circumlocuting the history Solís and McCoy photographed). I wrote snippets in my notes app as I listened. Solis in Mapping Session with Diana Solís, Evette Cordona, and Mona Noriega (Recorded Audio, 11:45 mins, 2024) described a raid on a lesbian bar, CK’s, I found it in the periphery of my gaze on the map she visited when she first came out around 1979. The curators described Solís as being able to sluice in and out of white spaces as a white-passing lesbian. McCoy described “hustlers” on a street corner with cars whizzing by (I could see Halsted’s traffic reflected in the glass casing of Harper Court Chess Players). McCoy reminisces in Mapping Session with Patric McCoy, Jim Harvey, and Anthony Jackson (Recorded Audio, 13:22 mins) about a place similar to the Bijou Theater, with rickety chairs and sticky floors. The curators described McCoy as primarily focused on the men-for-men underground scene.

There are often extrapolations and explorations within Chicago and national LGBTQ+ history that are, unfortunately, told through a static-y curtain. The flimsy facade of the white supremacist, heterosexist, capitalist patriarchy translates into the “homonormative standard.” Just Below the Surface works to skewer this.

During my visits to the exhibition, I voice-recorded the queer Chicago historical references that circuited in my mind. Folding into my research, the archival ephemera, collected in the glass display case off to the right, the pins on the map, the label information given, and how I walk back-and-forth through the exhibit):

- A hyper-local, mostly white, cisgender, gay group started a campaign in 2012 called “Take Back Boystown!” where they decried the proliferation of young people of color in the now-named North Halsted. They were described as the catalyst of crime and unsafe experiences when visiting The Center on Halsted, which is a resource of programs for the LGBTQ+ Chicago community. Over 10 years ago, it was one of few safe havens for queer Chicagoans (think again of the divide between the North and South Sides).

- Fun Home by Alison Bechdel: The subject of the book, the lesbian author’s closeted gay father, successfully slid in and out of gay life without notice. The gay men referenced by Bechdel—tertiary in the exhibition Just Below the Surface—mimic heteronormativity in their sexuality by recreating the nuclear family, while some members of QTPOC communities could not do the same.

- Darius Bost’s book Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence contains a chapter on writer Melvin Dixon’s journal-keeping. Bost writes that Dixon created a counter-history through personal narrative. His diaries fight layers of fabrication around queer experiences in the late 80s—examining the disregard for non-white and non-cis individuals. Bost wrote that Dixon explicitly stated his experiences interacting with the “negativities of post-Stonewall gay life,” wherein as an author he had to mutually-exclusively publish as either Black or gay in popular NYC publications.

- The Watermelon Woman: A fictionalized documentary by Black lesbian director Cheryl Dunye features herself as an aspiring filmmaker who confronts numerous hurdles while unearthing and documenting the life of an obscure actress, the Watermelon Woman, from the 1930s. Though the film doesn’t explicitly depict Cheryl being turned away from an archive, it showcases the archivist at the Center for Lesbian Information and Technology (CLIT). When asking for the section on Black Lesbian history, an archivist grabs a box and unceremoniously dumps its contents on a table, letting documents and photographs tumble.

Diverging, intersectional, and sometimes disparate stories and experiences—whether celebratory or revolting — make up the circuit of LGBTQ+ history.

The voltage of the exhibition caresses and punctures—showcasing Solís’s energy in lesbian spaces on the North side and lower West sides and McCoy’s gaze on underground Black gay spaces. As a side note, curator Flores shared that Solís and McCoy never (at least they think) crossed paths. Even in the queer community, the city was (and is) segregated.2 In an email, curator Alday stated the way to counter Chicago’s is to showcase the work further in the city and beyond. He described the exhibit moving on to other locations, “to create more intergenerational conversations.”

José Esteban Muñoz’s “Cruising Utopia” argues that the interconnectedness of non-conforming sexual or gender identities may exist only in a night, a place for a stint of time. I am left with the potential of liberation transferred into kinetic energy, led by Solís and McCoy. Through a cascading act of retribution, Solís and McCoy’s work buzzes with an aliveness. Even though intersectional queer critiques are often disregarded, the pulsing is there, ready for the team behind Just Below the Surface and more local queer historians to take the lead in monumentalizing these stories.

Footnotes

- Utilizing the term queer in this essay is a marker for representing sexual and gender minority communities. ↩︎

- A personal note: when I visited the exhibit and saw the archival-preservation case, a page of “Gay Chicago Magazine” from 1989 was open and showed an advertisement for Touché (a bar for men in leather and Levi’s). What came to mind was an event celebrating Touché’s 45th anniversary, which had a white ventriloquist come out with a Black puppet named “Sista Girl” in a minstrel performance. It was widely condemned and is a huge topic of conversation still within my circles in North Halsted. Below the Surface fights against the casting of queer politics and history through a white, cisgender, male gaze. I can feel the organic pulses magnetizing in the careful gaze of Solís and McCoy. They show moments of uninhibited joy and release in nightlife as my eyes caress figures in leather garb, figures dancing blurrily, and figures experiencing refuge among their community. Therein, one can hope—the best way to counter fabrications is celebrating every part of ourselves and the community. ↩︎

About the author: Originating from an evangelical community and contradictory motorcycle culture in Indiana, Samuel Schwindt left religion on the drive of highway 65 north to Chicago. Through his young-life he honed skills in wood and metal, and used his craft-history to receive a BFA in Studio Art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from University of Illinois at Chicago. Now, he works as commission-based leather-gear crafter, LGBTQ+ community organizer, site-specific installation artist, freelance writer, and adjunct professor at several institutions.