As I step through the entryway doors of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM), I feel transported into a different world. Although I grew up in the melting pot of Houston, Texas, I have spent the last two years becoming familiar with Kansas City’s art spaces and I ignorantly anticipated a similar older, wealthy, majority-white crowd among the visitors at the museum’s Fall/Winter 2024 exhibitions opening. However, if I had known that this kind of Missourian diversity was only a four hour drive away, I wouldn’t have waited so long to make this my first visit to St. Louis.

The opening on September 6 celebrated six new exhibitions, but the highly anticipated Great Rivers Biennial is the main source of the evening’s energetic buzz. Since 2003, the Great Rivers Biennial Award has recognized and fostered the creativity of artists in the greater St. Louis metropolitan area. Out of 96 applicants, three artists were selected by a panel of out-of-state jurors for their exhibition proposals that amplified ancestral craft and personal definitions of “home” through ceramics, paintings, video, textiles, and sculptural assemblage. For its eleventh iteration, the deserving recipients of the 2024 Great Rivers Biennial Award are Basil Kincaid, Saj Issa, and Ronald Young.

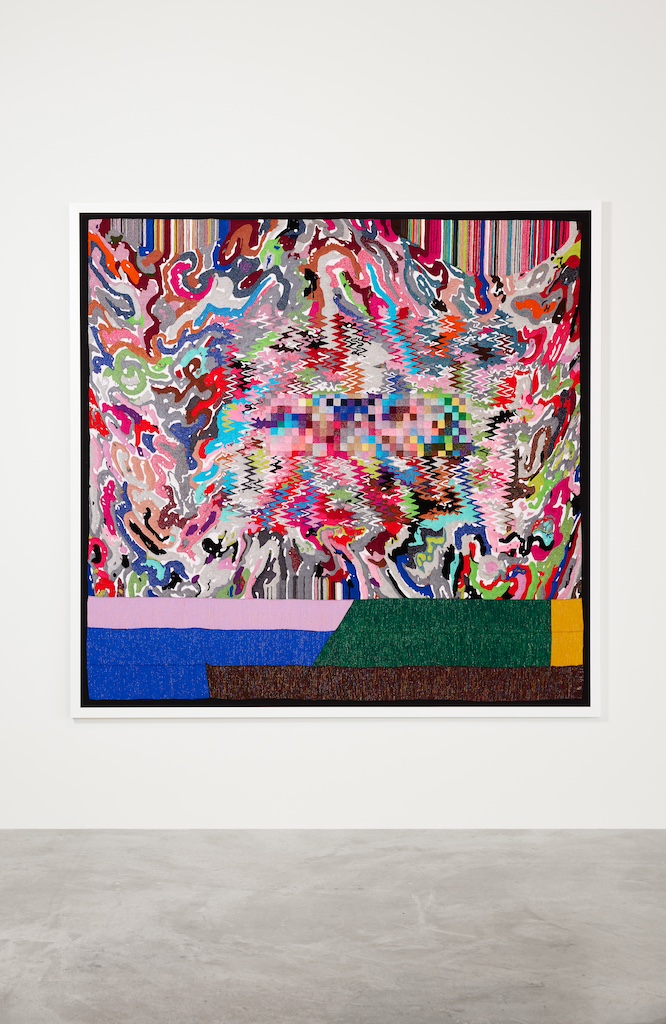

Upon arrival at the gallery, I pause to take it all in—the diverse community of people in attendance, the R&B music spilling into the space from the DJ in the adjacent gallery, and from where I was standing, I can easily preview the work of all three artists at once. To my left, the colorful fibers in Basil Kincaid’s Loose Frequencies dance and weave around one another within their white frame, seemingly echoing the energetic hum of excited voices that fill the gallery. To my right, nine figurative assemblages convene in a large bed of soil. These tall, wooden sculptures, adorned with jute spun into thick rope and found hardware, stand alert and at attention. Eight assemblages from Ronald Young’s Totem Pole series, guarded by the strong railroad spikes and a lightning rod that embellishes their counterpart, Gatekeeper, appears regal in stature; radiating an energy that whispers “I have a story to tell.”

On the far wall beyond Basil Kincaid’s fibrous colorwaves and Ronald Young’s altar for the industrial, the red flowers in Saj Issa’s Poppy Painting bloom with vigor against a gigantic bright yellow background. But the longer you spend time with the massive work, you eventually recognize that the center of the poppies are actually bullet holes, and what you mistook for stems is actually the spilling of blood. Issa’s use of poppies, the national flower of Palestine, is a violently beautiful reminder of the traumatic displacement, apartheid, and present-day genocidal acts the Palestinian people remain victims of at the hands of the Israeli government.

“Basil Kincaid declares that there are four qualities that are integral to the types of artists bred by the city of St. Louis: tenacity, resilience, resourcefulness, and potential.”

During a juror and artist panel discussion the morning after the exhibition opening, Basil Kincaid declares that there are four qualities that are integral to the types of artists bred by the city of St. Louis: tenacity, resilience, resourcefulness, and potential. The resolve in his statement resonates throughout the audience, and I begin to think about how each of these qualities are readily apparent in the intentionality, materiality, and execution of all of the works included in the biennial.

In Basil Kincaid’s larger-than-life quilts, his tenacity is driven by familial inspiration and a life filled with unconditional love. Kincaid’s abundant gratefulness is a guiding principle that builds upon generations of craftsmanship and cultural storytelling through the art of quiltmaking. During the creative process, he allows the fabrics to dictate their own shape, morphing into a colorful array of sensations that allow the viewer to become engulfed in the narratives they tell when completed.

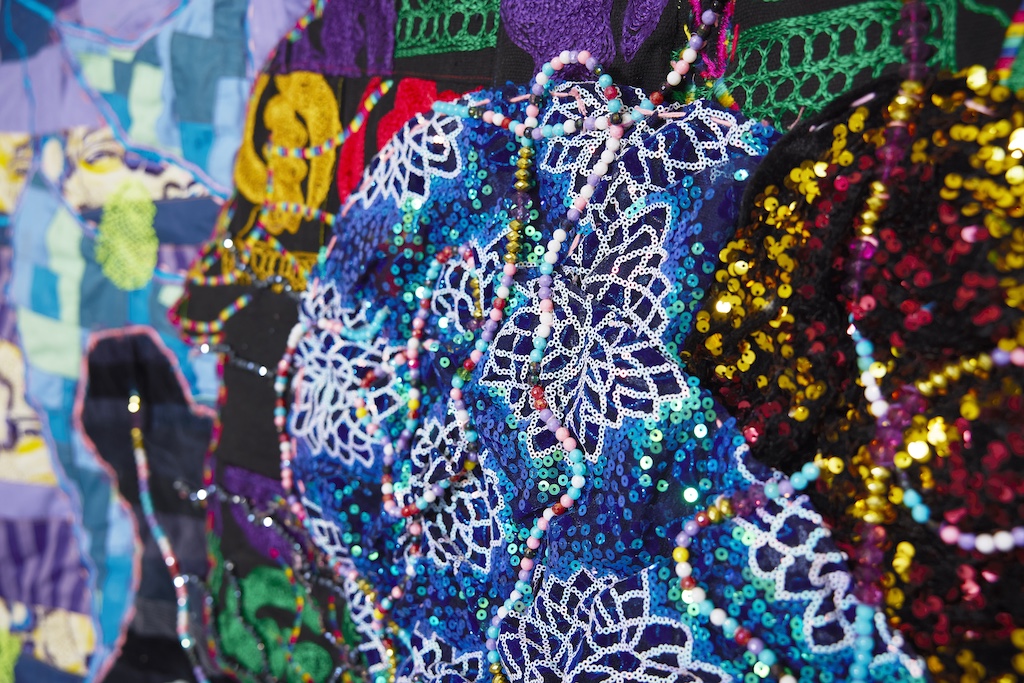

In order to grasp the totality of Basil Kincaid’s work, it is necessary to play with the physical distance between the viewer and the wall it hangs on. There is a delicacy in the curvature of the embroidered stitches and a playful energy among the twists and turns of the beadwork that reminds you of what it may feel like to view our solar system in a photograph of the Milky Way galaxy. When you zoom out beyond the Milky Way, suddenly you are reminded that we exist as a singular being, on a singular planet, that exists within a singular galaxy, that exists within an expansive universe of hundreds of billions of other galaxies.

In You Can’t Get To It Without Giving To It, and Within This Seed is the Gift of a Thousand Forests, figures crafted with colorful kente and Ghanaian fabrics commune to uplift the embroidered stars and beaded flowers that surround them. Up close, lines of sight can appreciate the detailed stitching used to bound the boldly patterned fabric to one another. But from a distance, Kincaid’s patterns and intricate details take familiar shapes as fingers, eyes, and human-like silhouettes. The ability to appreciate Kincaid’s work at both the small and large-scale adds to the dimensionality of the work and expands the viewer’s experience. Standing proud next to Basil Kincaid’s work, I feel small, in the grandest way.

For Saj Issa, the intentionality of her work is best understood by the resilience and history of the objects themselves. In Landscape Amphoras, 10th century pottery shards are glazed into earthenware that sit on steel rods, cradling dried floral arrangements. For Issa, every object she uses is selected with explicit intention. “History lies in the materials and collected things,” she explains, telling the story of how she stumbled across and excavated the ancient shards, a previously unknown remnant of a centuries-old creation, now displayed in a modern-day art gallery. At one point, the olive tree farm that the shards were found underneath belonged to a popular pottery shop in what is present-day Beitin, a rural village outside of Ramallah, Palestine. Saj Issa’s ceramic works and floral paintings investigate the multi-dimensional experiences of an object, and acknowledge the landscape as a holder of memory and narrative.

Saj Issa’s life experiences and familial narrative seep through the work and reflect an investigation of the political, cultural, and social evolution of the Palestinian landscape.

In Plein Air Performance, she films herself painting her view of a landscape on a hillside in Beitin, not far from her family home. Before she can finish her painting, she notices a patrol vehicle belonging to Israeli Defense Forces nearing her village and abruptly packs her things, leaving the beautiful scenery behind. Over the course of this 4 minute and 35 second video, the viewer bears witness to the arc of emotions the artist experiences—from contentment as she sips her tea and grazes her brush against the canvas, to fear as she realizes she is being watched by something other than her camera.

Like Saj Issa, seemingly unimportant materials have always been of interest to Ronald Young. His assemblages made from found objects speak the language of the discarded and forgotten; amplifying truths that deserve to be shouted from mountaintops. Having grown up just a few blocks away from the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, he has been a witness to the evolution of the surrounding neighborhoods he calls home. During the panel discussion, he recalls the nearby location of “Mill Creek Ashes”, the nickname for what was once Mill Creek Valley, a majority-Black community in Midtown St. Louis. The 1960 demolishing of this area closed hundreds of Black businesses and forced over 20,000 Black residents to relocate as a result of urban renewal efforts. Young says he walks by that area often, scavenging discarded items, asking himself, “do other people see what I see?” He lets his intuition guide him, leaning into the energy of his ancestors and the energies that live on in items that people commonly overlook and neglect as unimportant. His resourcefulness gives new life to industrial hardware and reminds us that even if the mind forgets, these objects—tangible remnants of what was—remember.

Many of Young’s assemblages appear human-like, each with their own personality and accents, inviting you to spend time with them to listen and learn about their experiences and personal narratives. Nails, charred wood, door hinges, and scrap metal cobbled together resemble nkisi, spiritual sculptures created by Kongo artists for African ritual ceremonies. These figures, created from objects discovered in the streets of St. Louis, exist as conduits for restoration and reparations; a sentiment of the artist’s deep love for the city.

The seamless blending of Black and Palestinian perspectives throughout the 2024 Great Rivers Biennial is what makes this year’s iteration so special. When asked how St. Louis cultivates such great artists, Saj Issa replied, “There’s something in the water.” Although the crowd giggled, there is a raw truth within her sentiment. In a city where Black and Brown people make up 48% of the city’s total population, there is a radical magic that manifests when historically marginalized communities are amplified in artistic spaces. Art has always been a catalyst for social and political action and the selection of this year’s artists are poignantly platformed. Various approaches to similar themes of ancestry, place, and objects as holders of memory allow each artist’s work to compliment the next and facilitate complex conversations about our individual roles as history writers and amplifiers.

The artists’ symbolic use of materials teaches viewers to see beyond the physical attributes of an object and instead, imagine its potential. On the cusp of a critical presidential election, Basil Kincaid, Saj Issa, and Ronald Young remind us that potentiality lies within the heart of the intended user. As long as we have the courage to imagine what could be, we will be granted the capacity to realize it.

* * *

The Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis’ Great Rivers Biennial will be on display until February 9, 2025. For a calendar of accompanying programming events, visit camstl.org.

About the Author: Kaitlyn B. Jones is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and independent curator committed to using art as a conduit for healing and a seedbed for activism.

She is an avid writer whose scholarship is rooted in the intersections of Black-American history and contemporary art. Through a multimedia semiotic lens, she explores themes of legacy, lineage and autonomy as it relates to the conscious and unconscious value placed on the histories and multifaceted cultures of the Black Diaspora.

She is the Founder and Chief Curator of Conduit Arts, a curatorial platform for research-based, community-oriented arts and culture projects that center Black diasporic histories, cultures, and perspectives.