This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

Para leer este artículo en Español, presione aqui.

A street photographer is often compared to Baudelaire’s flâneur: the anonymous wanderer who blends in and out of the crowd, observing and documenting the activities and interactions of city dwellers and their surroundings. Even when the photographed were made aware of the photographer’s intention, more or less, the subjects did not regard the photographer as anyone significant: their presence was no different than the absence. Hence, street photography might be one of the only ways to preserve life’s fleeting moments in a world where history rolls forward at an unprecedentedly rapid speed.

As part of the 2024 Art Design Chicago exhibitions, Harold Washington Library is displaying Japanese photographer Akito Tsuda’s renowned street photography series Pilsen Days. The exhibition presents over 100 of Akito’s black and white photos with the Mexican Community living, working, and growing in the Pilsen neighborhood during the 1990s.

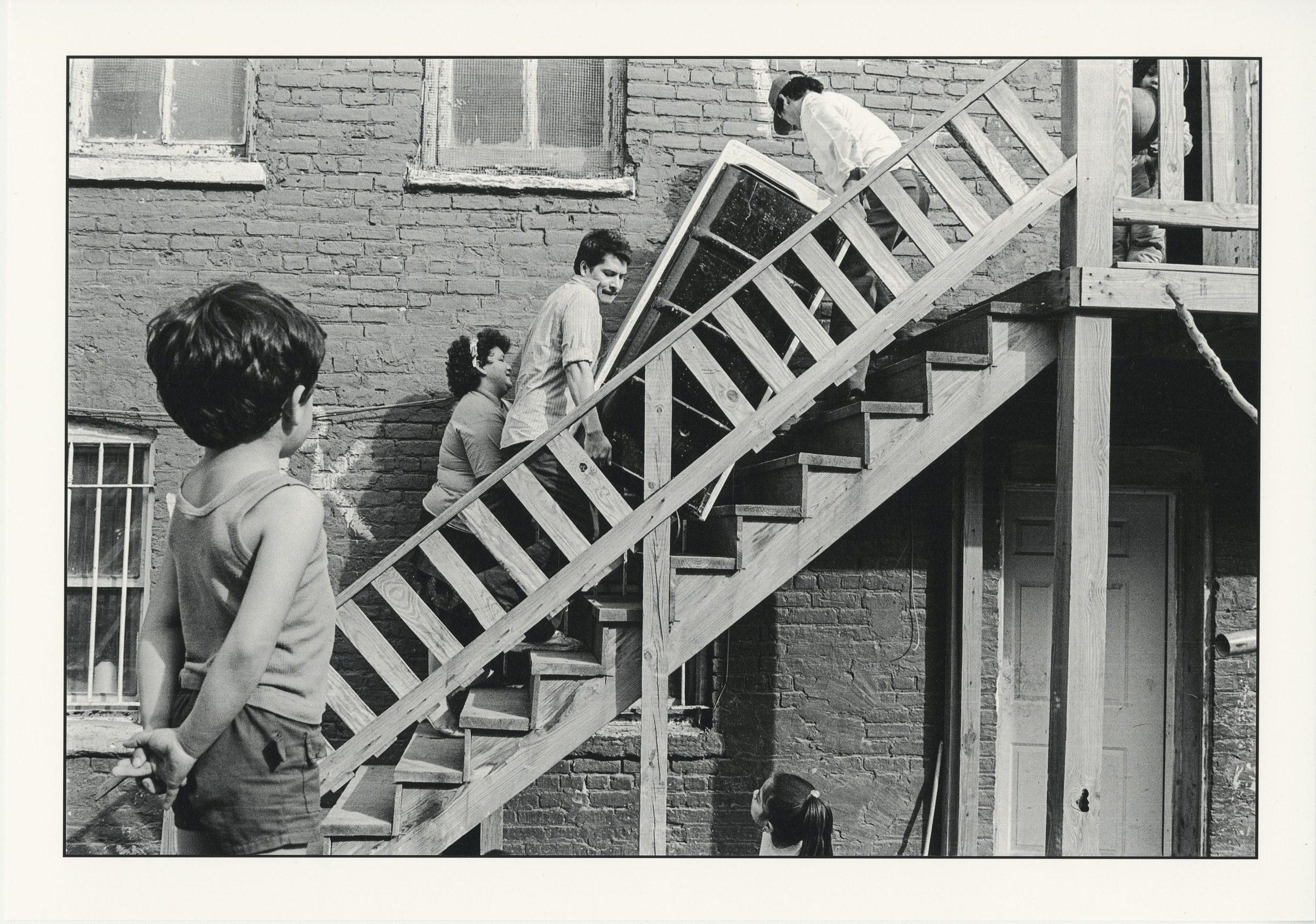

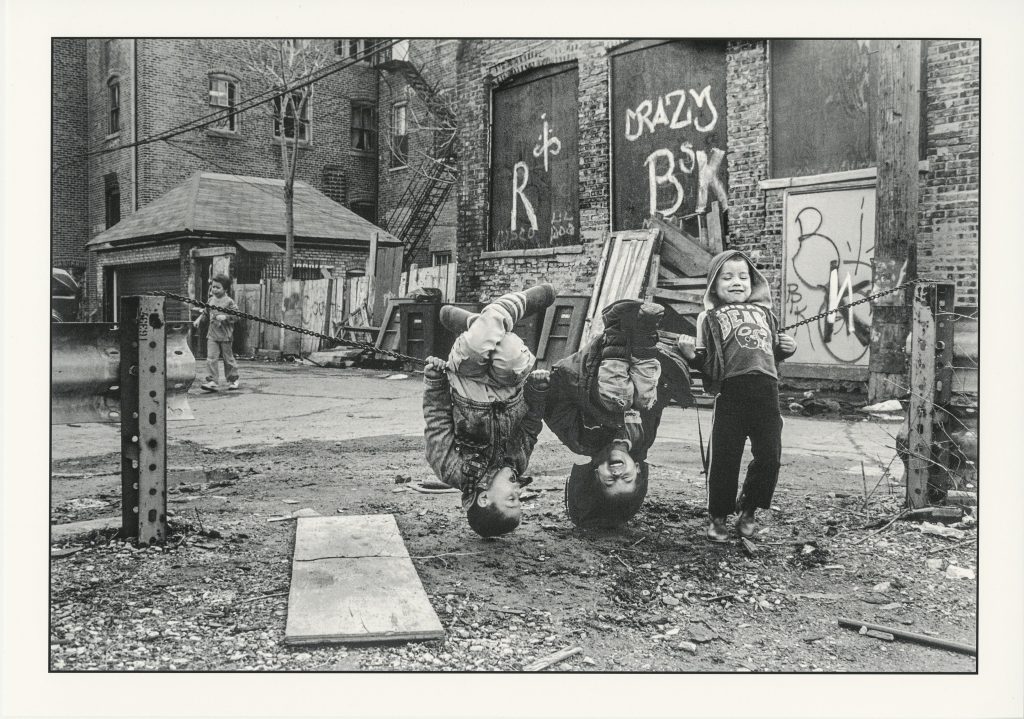

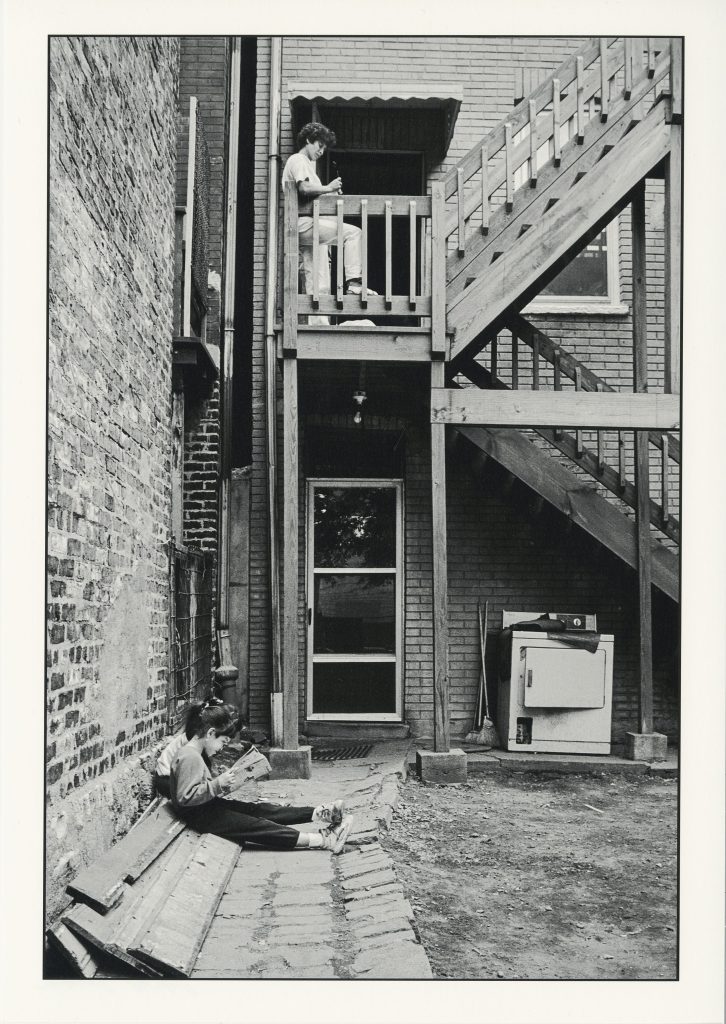

Pilsen has undergone drastic changes over the past few decades, like many other Chicago neighborhoods. The 90’s were a turning point: negative press coverages bombarded the neighborhood, highlighting gang violence and the dangers lurking around, laying the perfect conditions for developers to push for gentrification under the disguise of improved safety and the local economy. It was too convenient for those outside of Pilsen to simplify the neighborhood into mere keywords: chaos, crime-ridden, gangs, drugs, and poverty. Akito’s camera captured the undisclosed reality in Pilsen’s streets. In one photograph, a boy and a girl watch two men and a woman moving an appliance up the shabby wooden stairs behind an apartment. In another, three kids are hanging out at a DIY playground, two hanging upside down, giggling. You know, someone probably said these apartments weren’t safe to be around. But through the camera lens, all I see is innocence. This community was just living, making the best they could with their circumstances.

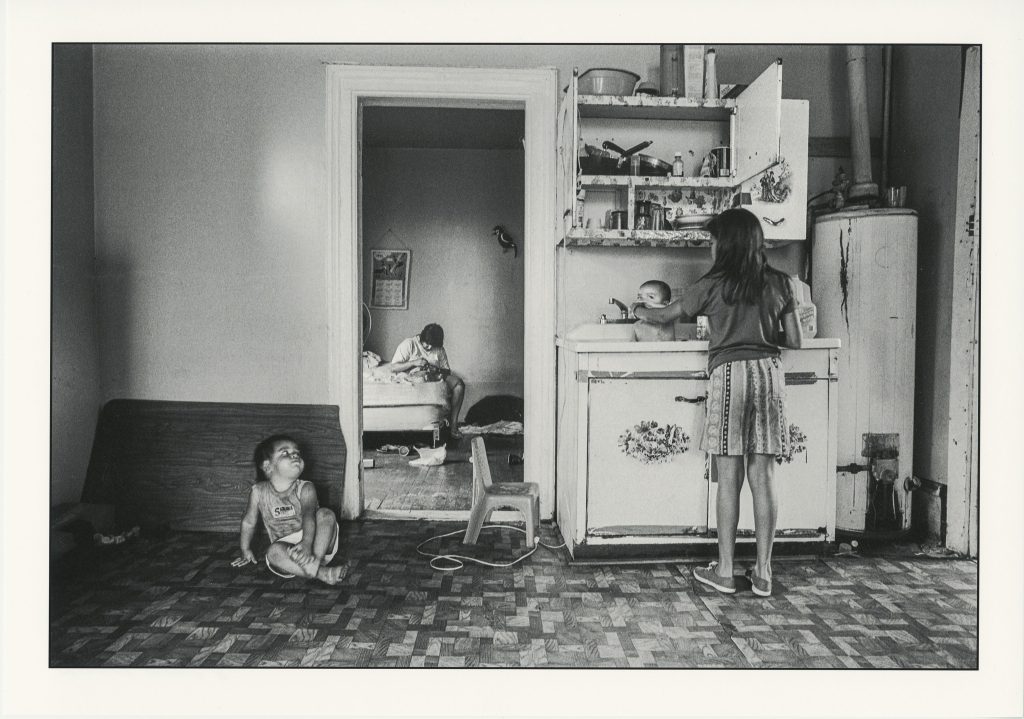

Though not included in this exhibition, my favorite photo by Akito is of domestic life. The elder sister is washing a baby in the kitchen sink while the middle child sits on the floor looking at her. In the bedroom in the back, someone who might be the mother sits on the bed sewing a shirt. This image, and many other photographs within the subject’s private space, touched me the deepest. In addition to a glimpse into their life, I also felt a deep-rooted generosity and kindness to have invited a young Japanese photographer into their home.

While looking through his photos, I couldn’t help but picture the young Akito who came to Chicago seeking clarity in life, barely speaking English, and never considering himself an artist. “How did you get them to let you take the photos, especially in their homes?” I asked during our call for this piece. And he answered: “I just asked really hard, genuinely: Please let me take your picture?”

“I visualized a young man who looked nothing like the residents of Pilsen walking the streets, holding his camera. He’d stop in the middle of the street to click his shutter, sometimes in pouring rain. Then, he’d approach someone on the bus or waiting on the curb and ask to take their photo.”

I visualized a young man who looked nothing like the residents of Pilsen walking the streets, holding his camera. He’d stop in the middle of the street to click his shutter, sometimes in pouring rain. Then, he’d approach someone on the bus or waiting on the curb and ask to take their photo. I wish another photographer were nearby. I wish someone else would have captured that scene. Thankfully, we can recreate that in our minds as we walk through the exhibition. Street photography has the ability to archive what exists on both sides of the lens, embedding the history of the photographed and the photographer. The dual-archiving is then manifested by an observer as they stand in front of the photographs now claiming the voyeur’s role: to observe the moment the image was captured from a third party’s perspective. In that regard, Akito and the individuals whose pictures were taken all become our subjects of observation.

Naturally, our curiosity as observers expands to the community the photographer belongs to: what were the living conditions of the Japanese community in Chicago during the same period?

When I first read about the exhibition on Art Design Chicago’s website, I found a Japanese photographer documenting Pilsen’s Mexican population rather serendipitous. In the 1990s, Chicago’s Lakeview used to have the biggest Japanese community, amicably referred to as Chicago’s “Japantown.” The neighborhood slowly dissolved as a result of forced assimilation, pressuring Japanese communities to hide their heritage and identity. While many businesses remained into the latter half of the 90’s, gentrification and changing neighborhood dynamics, coupled with lack of residential and commercial succession, had significantly diminished the area of Nikkei presence.

The Japanese migrants in Chicago came under a situation unlike any other. In 1944, a 20,000 Japanese population was resettled by the U.S. government from WWII incarceration camps. As part of the procedure, the officials pressured them to conceal their Japanese identities and assimilate into white America. One had to basically be unseen. However, it is a member of this largely invisible community that documented another population that was rendered invisible to the public: the Mexican residents of Pilsen. Didn’t Akito’s lens unintentionally become a documentary of his history? That passive recording of his existence further prompted me to learn about Chicago’s Japanese history, finding connections between two migrant communities in Chicago whose experiences, though vastly different, shared certain similarities in the face of gentrification.

Looking at Pilsen Days, I began imagining the lives of my ancestors and felt a renewed connection between memories of my youth and those of the tens of generations of Chinese migrants before me. I wondered about how they lived during the 1800s, when the Chinese population first migrated to Chicago to build the transcontinental rails. I closed my eyes and saw kids giggling and jumping into rain puddles, or doing homework on the floor, or making a meal standing on a wooden stool while their parents were away at work. I imagined women like my mother and grandmother walking home from a trip to the neighborhood grocery store and men like my father and grandfather sitting by the railway stations in construction gear, chatting with a cigarette in their mouth after a long day’s work. Akito’s lens becomes a viewfinder, allowing me to peep into the histories of Pilsen’s residents, and that of Chicago’s Japanese population, and my own: Chicago’s Chinese community.

Chinese Chicagoans always leave a memorable impression on first-time visitors and longtime residents alike. Yet, little known to the public, there was once a “Chinatown” in Chicago’s bustling Downtown where Chinese laborers first migrated to during the railway construction on Clark Street running from Van Buren to Harrison in the 19th century. As developments rolled out Downtown in the early 20th century, the cost of living became unaffordable, and the Chinese population migrated south to where today’s Chinatown resides. Today’s Chinatown is a robust, vibrant, and creative neighborhood like Pilsen.

“One history becomes the reminder of another, intertwining individual and collective experiences and weaving a profound narrative of life and living in the past, the present, and the future.”

In 2002, a photography exhibition at the SAIC titled Photographer, Subject, Viewer: A Triangulated Relationship asked the following questions: “How does a picture reveal the relationship between the photographer and the subject—whether intimate or detached, reverential or condescending? How does the subject anticipate a future viewer? And finally, how do viewers respond to the pictured subject as mediated by the photographer and the camera?” In street photography, I see this triangulated relationship morph into a tripartite lens: the lens through which Akito captured his subjects, the lens through which his subjects saw him, and the lens through which the photographed, the photographer, and the viewers interconnect. One history becomes the reminder of another, intertwining individual and collective experiences and weaving a profound narrative of life and living in the past, the present, and the future.

Today’s Pilsen is a robust and vibrant neighborhood flourishing with art, business, and a glorious community proud of its Mexican heritage. However, gentrification’s shadow also continues to hover. According to South Side Weekly coverage, property taxes and rent prices are at an all-time high in Pilsen, and the flourishing Airbnbs in the neighborhood work as a catalyst for gentrification.

As a result, the individuals, tired of beaming in front of Akito’s lens, are at stake. In a way, this exhibition is an emotional reminder of why a neighborhood’s development must always keep its residents at heart and that behind the blooming tourism and another beautiful restaurant are people who might have been working and living in the neighborhood for decades. The story of them, him, and us continues. Hence, the photographs are more than an archive. Use them to reflect upon our present and guide us into the future.

Akito Tsuda: Pilsen Days is on view on the 9th floor of the Harold Washington Library Center from June 3, 2024 to December 31, 2024.

About the Author: Xiao Faria daCunha (she/her) is a practicing visual artist and an independent journalist covering what’s happening in the Midwest belt, focusing on lifestyle, art, and culture. Her visual art practice includes mixed-media illustration on paper, printmaking, and mixed-media collage. Xiao was the former Managing Editor for Urban Matter Chicago and her bylines have appeared in Chicago Reader, BlockClub, BRIDGE.CHICAGO, KCUR, and more. Xiao’s artistic and writing practice explores the intimate, vulnerable truth of the BIPOC, migrant, immigrant, and diaspora communities. She considers everything she does art journalism and aims to speak on behalf of those who haven’t been heard and shed light on what hasn’t been seen, whether it’s emotional, cultural, or societal. By weaving her personal experience with public narratives, Xiao creates emotional and engaging conversations to interrogate, challenge, and advance existing perceptions of women, Asian diasporas, and other immigration populations.