Featured image: An installation view of General Objects at Heaven Gallery showing seven pieces. From left to right: Site-geist (Masking) & Site-geist (Erasure) by H Lawson [two screen prints showing city scenes], Double-sided Outside by Catherine Hu [a partition-like structure that looks like the side of a light blue house], Big Boy (Diamonds) by Conrad Cheung [a large king of diamonds card leaning against the gallery wall], (carhartt hat arch) by Gary LaPointe Jr. [two concrete hats facing each other sitting on the gallery floor], Impotent Screen by H Lawson [a screen print on hand-dyed green utility cloth hanging on a wooden structure with a circle towards the top], and Twice as Far Away (Street Trash Can) by Catherine Hu [a life-size black trashcan installed in the gallery]. Image courtesy of Heaven Gallery.

I have a cup in my hand. It’s comfortably weighted, only lightly tugging at the tendons in my wrist. Made of porcelain, sturdy in its quality, dainty in its litheness, the cup could hold eight ounces. I imagine the cup in the hand of a loved one, drinking lemonade after a day of helping me with yard work. I picture the cup stacked hastily amongst the rest of my dishware in the sink, steeped in damp coffee grounds. I own enough cups, so I put it back on the shelf alongside twenty-nine identical cups, and walk away. I think about how the cup balanced so easily in my palm, and I return to the shelf that displayed it. Thirty uniform porcelain cups organized as a militia stare back at me. I pick up the cup I held earlier, the base still warm from my grip, and walk to the cashier. I could have picked up any of the thirty cups, as they were constructed with precise replication of one another. But, I hadn’t imagined those cups quenching the thirst of my loved one, or pooled in my mess of coffee grounds. The cup in my hand had an important future ahead of it, and I could no longer see it as merely an object, inconsequential from the rest.

An object, from its design to its production, remains an object. Significance is then assigned to it by the context for which it’s placed in. Context can be given in different ways, and artists have been grappling with recontextualization for decades. Context can be the environment that houses the object. The introduction of the “readymade” in 1916 took an object from everyday life and placed it within the white cube of a gallery. Context can be the value an object has. In 1965, Donald Judd introduced “specific objects,” where emotional value or representational value is stripped away by classifying a piece as an actual item, rather than as an artwork. This removal of all other context allows for an emphasis on pure formal qualities, such as space, color, and dimension, as exemplified by Judd’s most recognized Untitled (Stack) series. Context can be significance placed upon an object by humans. Emotional implications, historical significance, political investigations, to existential quandaries can be read from an otherwise insignificant object, by the artist’s gesture. General Objects at Heaven Gallery, curated by Danny Floyd and Jeffery Prokash, features the work of Conrad Cheung, Catherine Hu, stephanie mei huang, Gary LaPointe Jr, H Lawson, Clayton Phillips, and Unyimeabasi Udoh. Challenging and temporal, General Objects is steeped in art objects that disregard, interrogate, and humor the classification of the object itself. I spoke with one of the curators, Jeffery Prokash, about the exhibition before viewing:

“This is the second General Objects exhibition. The first was in 2014, curated by Danny Floyd. That exhibition was based on a conversation we were having on a project that I was working on with the windows from Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Women’s Hospital. The windows are 7 x 5 feet tall, oval shaped, and are located in a brutalist concrete building here in Chicago. They have a minimal, Donald Judd-type aesthetic to them, but they are unspecific in that they are also just windows. This also brought along another context. At the time, people were protesting in favor of Goldberg’s building in an effort to prevent them from tearing down the iconic structure these windows were located in. It turned into a big political disagreement that unfolded in the city. Floyd and I were captivated by this idea that some people would look at these windows and only see them as a Donald Judd, minimalist, ‘specific object’ gesture, while other people were having an entirely different encounter. We were having a conversation about how an object can pull in meaning (even if it is just a window), and the term ‘General Object’ came out. It was a lightning strike for us where we considered how Donald Judd had taken all of this effort to define what ‘specific objects’ were. It occurred to us that this concept of ‘general objects’ was presently having the same kind of moment that specific objects did in the time of Judd.

“[General objects] is a concept that we’re grappling with on a larger cultural level in the art world. Readymade, ‘specific objects’, and Minimalism gave us permission to bring something like a dirty Carhartt hat into the gallery space. Because those previous movements existed, we can have this new conversation about recognizable, insignificant, rudimentary, and quotidian forms, that then makes a space for meaning to be attached. Donald Judd defined ‘specific objects’ as things that exist unto themselves in the gallery space. ‘General objects’ are almost the opposite. They become this lightning rod for meaning because everybody can recognize a door or a window; it’s a blank slate, but when the artist applies their maneuver, they are then shifted. The artist’s gesture of making pulls it out of the space of reality and puts it specifically into the exhibition space. At that point in time, it becomes a sculptural object that is then conveying meaning other than its original. It’s a concept that’s still being formed. Over time, we could establish a clear set of rules in the same way that Donald Judd used to define ‘specific objects’.”

![Image: An installation view of General Objects at Heaven Gallery. The four pieces shown are as follows from left or right: Big Boy (Diamonds) by Conrad Cheung [a large king of diamonds card leaning against the gallery wall], (carhartt hat arch) by Gary LaPointe Jr. [two concrete hats facing each other sitting on the gallery floor], Off White and Hickory (Door) by Conrad Cheung [a sliver of a white door with a silver handle leaning against the gallery wall], and Twice as Far Away (Street Trash Can) by Catherine Hu [a life-size black trashcan installed in the gallery]. Image courtesy of Heaven Gallery.](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ROOM1_20211218_05-1024x768.jpg)

In the first room of Heaven Gallery, the viewer is immediately confronted with an oversized door placed strategically next to the entrance door of the space. Roughly twice the height and a third of the width of a standard door, Off White and Hickory (door) by Conrad Cheung dauntingly looms over the viewer. If this sculptural object was on its own, the impact would suffer. The context that the space provides in addition to the placement next to the actual physical gallery door creates a jarring dissonance between the two objects. Cheung’s gesture is applied by stretching the height of the door and squeezing the width. Moving counterclockwise across the room, the next piece, also by Conrad Cheung, reflects a classic king of diamonds from a standard deck of cards. The gesture applied here is another play on scale, as the card is enlarged to a human-like dimension. The head of the king is roughly the size of the head of a viewer, and it delicately rests nuzzled between the wall and the floor, sloped as if it’s relaxing.

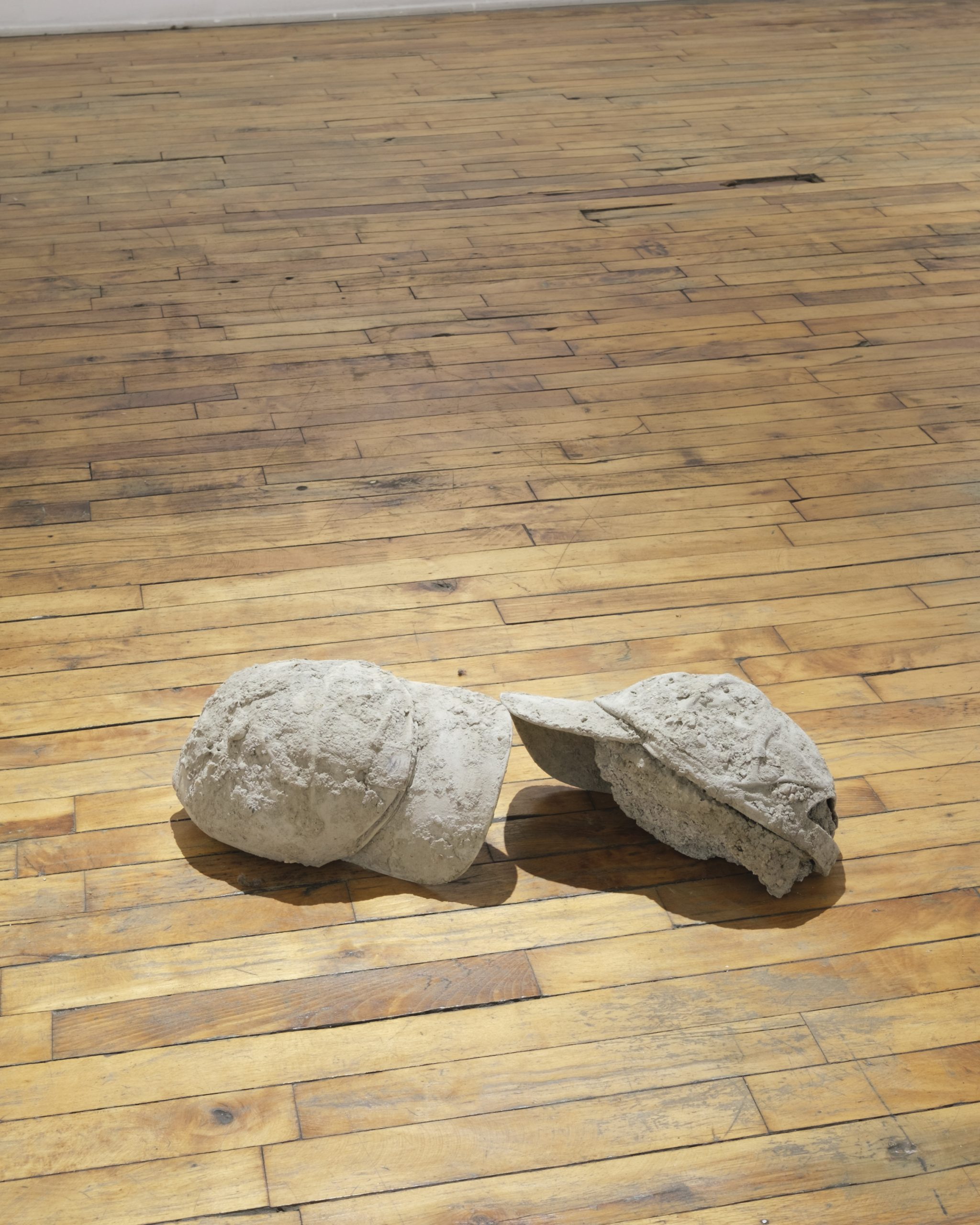

On the floor in the center of the space is (carhartt hat arch) by Gary LaPointe Jr. Two Carhartt hats, entrenched in concrete, face one another with the tips of their brims gently colliding. Carhartt as a brand has a history of blue collar, working class consumers. This history combined with the heaviness added by the concrete makes these objects separately hold a weighted, masculine presence. The artist’s gesture of positioning them so that they not only face one another, but also gently touch, creates an undeniably tender feeling of intimacy. The viewer can easily imagine the two figures beneath the hats sharing a stolen kiss, shattering a gendered construct in their bold wake.

Left image: Catherine Hu, Double-sided Outside, 2020, painted MDF, print- transfer on pine, floral fabric, 32″ x 36″ x 30″. A partition-like structure that looks like the side of a light blue house with a window. Left image: Gary LaPointe Jr., (carhartt hat arch), 2019, Carhartt hats, concrete, 5.5″ x 8″ x 25″. Two grey life-sized hats sit on the gallery floor. They face one another and slightly touch. Images courtesy of Heaven Gallery.

Also positioned on the ground is the piece Double-sided Outside by Catherine Hu. Made of MDF and floral fabric, this object resembles a portion of a house, dramatically scaled down from a livable home, yet simultaneously scaled up from the size of a classic doll house. It’s lack of closure invites the viewer to consider the object from all angles, confusing the line between outside and inside. Standing in the crook of the sculpture’s bend, the viewer is positioned perfectly to gaze across the gallery space and make eye contact with four of Unyimeabasi Udoh’s cross-stitched embroidered pieces, titled OH NO (Is It Flooding or Am I Failing to Swim?), ALL RIGHT, I CANNOT, and HELP YOURSELF. These works offer an opportunity to consider text as an object, as each cross-stitch includes the title embroidered in the center of the circle. By removing context from the text, the artist gives proper attention to the given words, allowing only the context of the object itself to remain. Especially notable in OH NO (Is It Flooding or Am I Failing to Swim?), the viewer is left to place this written information into their own context. “Oh no” fills many gaps in conversations, from reacting, to being genuinely frightened, to haphazardly letting it slip from your mouth when you’re no longer listening to someone.

Dominating room two of the gallery, Gary LaPointe Jr.’s piece (idle engine, collection of six black solar panels) is positioned on the wall. Subtly reflective and richly dark, each panel serves as a magnetic force, sucking the viewer deep into these mysterious, window-like realms. Purchased from doomsday preppers, these solar panels had a purpose before entering the gallery space. At one point, a family was planning to depend on these. Stripped of that context and placed within the gallery walls, they become blank, screen-like objects of confrontation. It is impossible to walk by them without staring back at yourself, getting lost in the separation between our current reality and fears of the future.

Walking clockwise across the gallery, the piece Pew by Clayton Phillips replicates a church pew made out of MDF and foam. Though the gesture of moving this recognizable object from a church and placing it within the gallery itself is interesting, it does not constitute as the artist’s gesture. Rather, the addition of the literature, and the specificity of the literature, that sits on the back of it is where this piece becomes a “general object”. Books titled Redesigning the American dream, Sculpture and its Reproduction, How to Coach, Manage, and Play Little League Baseball, and a book where only the word “Holy” can be read, appear in a line. Each title is deliberately chosen as a metaphoric easter egg, calling back key points to the rest of the exhibition.

Moving across the gallery, the viewer meets the piece Violin by Catherine Hu. The sculpture could easily be confused with a ready-made, as it’s made precisely to represent a violin, indistinguishable from a playable violin. The artist’s gesture here is that this instrument is not playable, and the viewer would have no way of knowing that unless they picked it up and tried. The intense labor of making an object unambiguous from what it represents and meticulously crafting it so that its “purpose” (producing music) is implied enough that its “uselessness” goes unnoticed, is remarkable. Hu’s dedication to separating it from a real violin successfully constitutes this piece as a general object, and tugs at the vein of the “general object” itself.

Challenging the classification of the object by changing its context, poking at its emotional implications, dismantling its structure, and appending upon its intended purpose leads to a space filled with thoughtful, surprising, and most importantly, general objects that were perhaps once insignificant, but that are now changed by the artist’s gesture.

I hold the cup in my hand, half-full with my ritualized nightly chamomile tea. I remember the time I poured too much and burned my lap in the overflow. The cup and its use, once imagined and dreamt, has now become part of my tangible memory. My cup is no longer just an object. Through pacing around the store with it balanced in my palm, to setting it on the far left side of the shelf in my cupboard after every use, my own transformative gesture has been made.

Ally Fouts is an artist, designer, and writer living in Chicago. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Art, Media, and Design from DePaul University. More information surrounding her artistic practice can be found on her website.