Featured image: A screenshot taken during Bimbola Akinbola’s performance Evidence. Akinbola presses her face into the canvas. Her hair covers her face, with her hand supporting her to the right of her head. Image by Benji Hart.

On January 18th, 2022, interdisciplinary artist Bimbola Akinbola performed a new entry in her evolving series Evidence on the In Progress stage at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Akinbola is Assistant Professor of Performance Studies at Northwestern University, the daughter of Nigerian immigrants to the U.S., and identifies as queer. In this series, Akinbola rubs her cosmetic-covered face on blank canvases over an extended period (in the case of the MCA performance, about 40 minutes), using the residual smudges to produce visual works by the end of the exercise.

In the artist’s own words:

“The series explores my interest in the relationship between the moving body and the medium of painting, particularly in how the liveness of the moving body can be captured in painting…The work tells stories about the unspoken truths bodies reveal in space centering on shame, alienation, and the lingering nature of our existence.”

Because of a surge in COVID cases due to the Omicron variant at the time of the performance, I attended virtually.

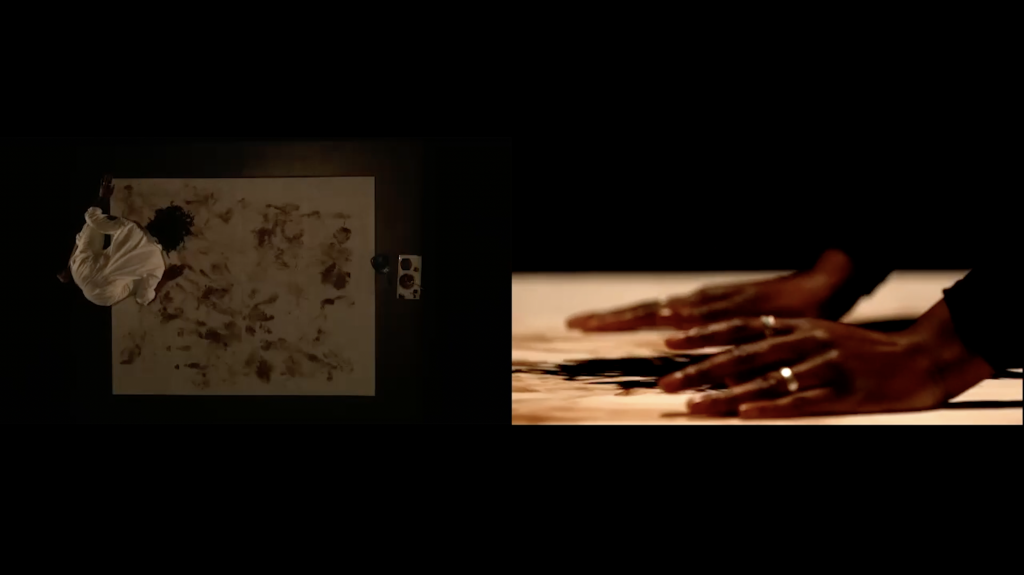

Before we see anything, we hear Akinbola’s slow breath broadcast over speakers through a darkened theater. The lights come up, and the virtual viewer sees a split screen: on the left, a livestream of the artist in an all-white jumpsuit sprawled across a body-sized grid of overlapping white sheets of paper on the MCA stage, her jet-black Nubian twists obscuring her face, which is already pressed to the ground; on the right, a prerecorded video of Akinbola in almost the exact same position, but in all black, the camera only inches from her face.

In both frames, the artist begins fretting her face against the blank canvas in long, methodical motions, shifting from crouched to lying positions as needed, but rarely lifting her face from the floor—with the exception of the intermittent reapplication of her makeup with a brush housed on a white tray just off the large paper.

Particularly in the right frame, Akinbola makes direct eye contact with the camera, especially as she works a cheek or her chin on one area of the canvas. Her lower lip is sometimes pulled downward, distorted by the effort. From an aerial view, we see brown streaks beginning to snake like fossil rubbings, unreadable tracks, across the paper. Her breath continues.

A few minutes in, a recording of the artist’s voice unexpectedly begins playing over the speakers, reciting a numerated list:

“1. A cheek print on a green couch cushion at a stranger’s home.”

The voice is layered over by the occasional click of the brush returning to the tray, the monotonous rustling of fabric against canvas, of Akinbola’s extensions as they drag through the markings she leaves.

“3. Brown smudges in the margins of a borrowed book.”

The piece’s minimal palette—up to this point, only black, brown, and white—becomes enlivened by the snapshots provided by the recitation, expanding in tone and form. The growing streaks on the paper, illegible a moment ago, are suddenly invested with new meaning, new lives. A scuff generated by Akinbola’s cheek on the canvas could just as easily be a stain on her partner’s gray sweatshirt, or her own shirt cuff; her movements, at first random, are now “an exaggerated stretch of the neck to avoid a crisp, white collar.”

“9. A greasy print on the dance studio floor in the shape of my thigh.”

I am suddenly in Iowa City, Iowa where I lived as a child, changing in the locker room of the public pool we frequented, and where we were often the only Black family. My dad insisted on putting lotion on me after getting out of the showers, and I viscerally recall the mortification of being the only child made to go through this ritual. (There’s a favorite family story of the day when a little white boy observed us, and said accusingly to his own father, “How come you never put lotion on me?”) The azure tiles in the showers, the red and white lane lines bobbing in chlorinated water, vividly evoked by the audio, overlay themselves instantly onto Akinbola’s movements, so that I can literally see them simultaneously. (Alongside yet another memory of watching “Coming to America” at my childhood friends’ house, the scene in which Soul Glo drips down the back of a tan sofa, evidence of those who had just been seated there.)

As Akinbola’s own ritual continues, the voiceover begins to elaborate on individual items from the litany, in no particular order. It zeros in on #5, “a spattering on the light switch” in her parents’ apartment:

“…When I see it, I’m grossed out by it…I’m reminded of my mother, and I’m imagining her running around before going to church, turning the light switch on again and off again, and covering the walls in the brown of her makeup. And I want to wipe it away and I also want it to stay there forever.”

Encapsulated in one image, these are the piece’s central meditations: the ways Blackness, refracted through womanhood and queerness into something even more unnamable, is tangibly memorialized through the brown, buttery residue of makeup, hair, and skincare; how shame and pride are inseparable, maybe even dependent on one another; the tension between what we’ve been taught to love and despise most about ourselves, when they are so frequently the same things, so often imbued with preciousness and disdain by the same sources.

The litany restarts. (“14. Like dirt collecting under my nails every time I touch my face.”) On the right side of the screen, the artist comes to her knees and fans herself with both hands, her forehead glistening with sweat. At this phase, there are markings in all four quadrants of the canvas. The breath reemerges, and is matched by a cacophony of multiple speaking voices, items and anecdotes competing with one another to be heard. We can make out the names of foundation colors (“…cappuccino, mahogany, coffee…”) lifted from a beauty supply aisle.

The artist rolls her nose, lips, eyelids, and cheekbones in one last pass over the canvas, as the voiceover recounts a dream: Akinbola in a coffee shop with a group of other Black women, who all simultaneously realize they have makeup stains on their white dresses:

“It’s okay. It’s all okay.”

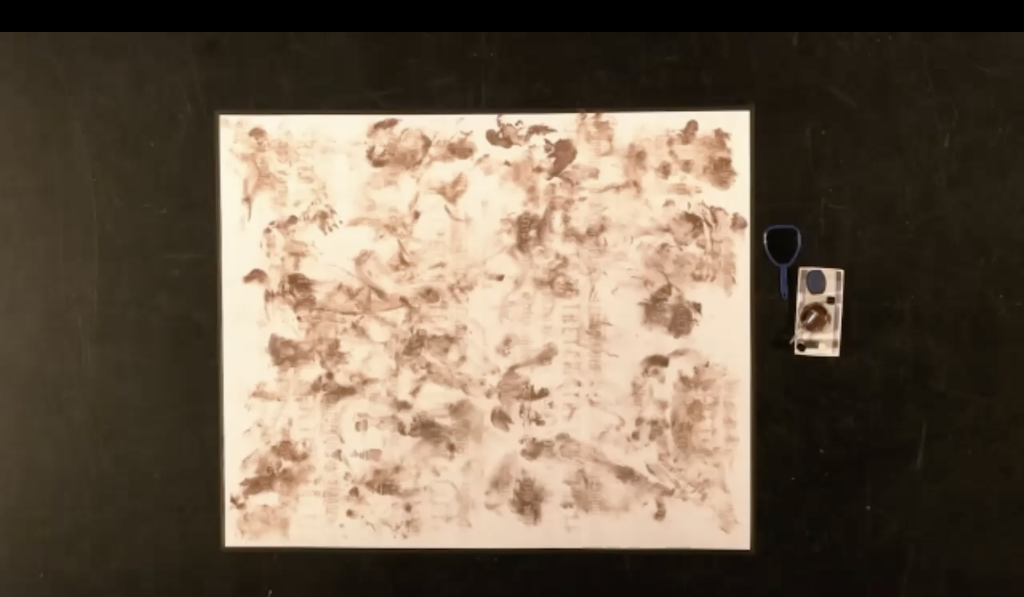

In a final pose, backside lifted, palms and forehead pressed to the paper, Akinbola rises, appears to survey the canvas for the first time in its totality, then exits stage left.

Audience members are invited to come onto the stage and view the final product up close. We can see that the canvas, while still bearing plenty of white, has large smudges in every corner, looking like an asymmetrical Rorschach test. As the camera moves closer we can see watermarked wording referencing lines from the spoken text, visible from behind the makeup stains.

I was left reflecting on the ways my identities and experiences connect with Akinbola’s (primarily via Blackness, femmeness, and queerness) and the many ways they don’t (I’m non-immigrant, light-skinned, do not identify as a woman, rarely wear makeup). I remained captivated for hours afterward by the lingering images evoked by the piece’s text, the Magic-Eye-effect in which the artist was able to conjure my memories by sharing her own, to make me see vast geographies and assorted colors on nothing more than a white canvas with brown makeup.

Some strictly aesthetic thoughts I have for the artist at the end of the viewing:

The reveal of the watermarked paper—a new element Akinbola experimented with in collaboration with visual artist Angela Davis Fegan for this performance—made for a nice connection with the spoken text, but also visually interrupted the movement of the makeup on the canvas. In previous entries, the brown smears are boldly highlighted against a plain white background, whereas with the introduction of lettering, it seemed as though the smears were doing the highlighting. I’m curious whether the artist found this contrast enhanced the core themes, or distracted from them.

Also, other completed canvases in the Evidence series include graphite accents in tight groupings of parallel lines that wing and woosh inside the larger swooping smudges. I loved the way these smaller strokes added depth and dynamism to the broader movements of the makeup marks. Is incorporating pencil drawing into the performance a possibility, so that the canvas we see at the end of the staging includes these more intricate additions?

Bimbola Akinbola’s ability to generate a complex visual experience with such sparse elements reveals just how well she chose the materials for Evidence—not just paper and makeup, but the repurposed leavings of her own life as a Black queer woman. It’s difficult to create a work whose process is just as compelling as the final painting it produces, but she does so simply, convincingly.

The same exaggerated stretch of the neck meant to avoid marking one surface is the precise movement that intentionally marks another. The succinct capturing of this tension, the embodiment of this conundrum, is the genius of this work.

Benji Hart is a Chicago-based author, artist, and educator whose work centers Black radicalism, queer liberation, and prison abolition. Their words have appeared in numerous anthologies, and been published at Teen Vogue, Time, The Advocate, and elsewhere. They have been a fellow with the Rauschenberg Foundation, MacDowell, and are a 3Arts awardee in the Teaching Arts. See more of their work at BenjiHart.com