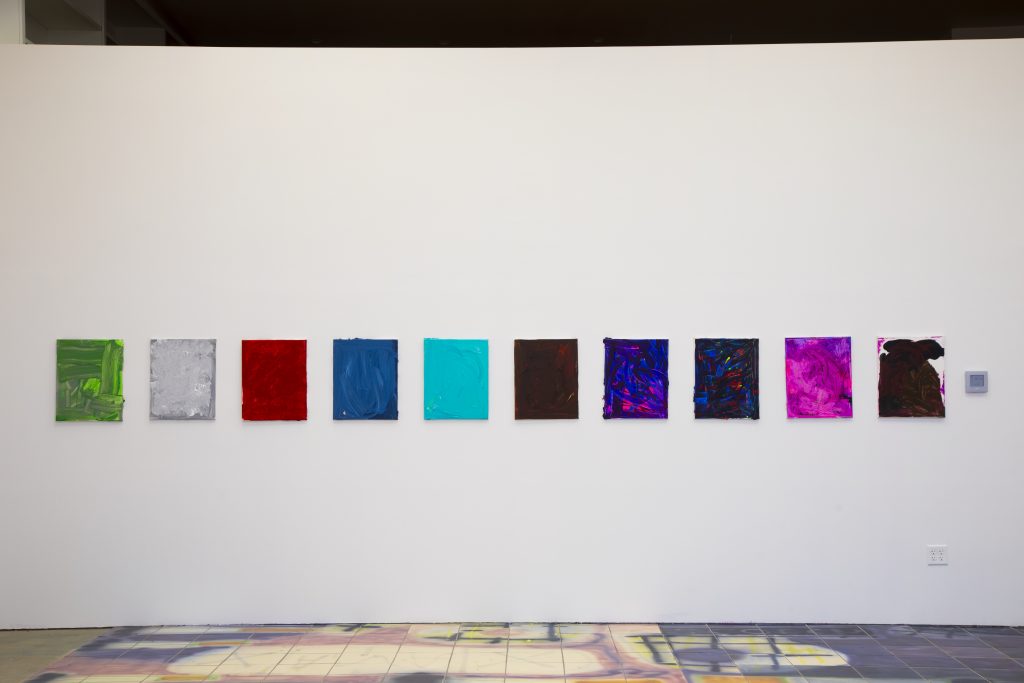

Featured image: A view of Khalifa Jdia-Burnhardt’s solo exhibition at Dragon Crab Turtle. A selection of paintings on canvas are hung in a ‘t’ format on a white wall to the left. On the right, the works are all non-representational in style and employ thick brushstrokes. The gallery floor has a colorful, graffiti-like image on it. Image courtesy of Dragon Crab Turtle.

Consider him as a man-child, as a man who is never for a moment without the genius of childhood — a genius for which no aspect of life has become stale.

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”

There’re a lot of cutesy ways to start the type of review this one ought to be, but I think that for the sake of honest engagement it’s best not to bury the lede at all: Khalifa Jdia-Burnhardt, whose current solo show at the St. Louis gallery Dragon, Crab, and Turtle (DCT) contains a couple dozen recent abstractions, is 10 years old. His mom, Katherine Burnhardt, is DCT’s owner-operator, and is also an artist herself. In the show’s promotional material, she writes of some of Khalifa’s bustling monochromes that there is “a calm in [their] chaos [of] layered brush marks.” Of some of his stark black-and-whites — all done thick-lined with a nicely heavy hand — she says that her son’s framing and focus morph quotidian objects into “abstracted lines in their simplest form.” Neither statement is off base a bit, nor would be bigger plaudits. In fact, if I hadn’t been told straight away that Khalifa’s a kid (particularly a kid whose mom is in a position to make conceptual-ish moves by putting his art up in her gallery), I almost certainly would have engaged with his paintings unreservedly, just as I would have those of an adult artist. It’s unlikely I would have been overly disappointed, either.

While a few of Khalifa’s canvases did indeed look characteristically childish, most of them were energetic and richly simple. Of those monochromes his mom described, an orange one draped in layers of its own umber stood out to me especially. Its random runs of paint over paint gave the surface a nice sense of heft, in the same way that a fire flickering seems to participate in mass. The quick representational pieces, too, had some undeniable spunk. Consisting only of big black lines dragged or smudged on small white surfaces, they were all done with a satisfaction in their completion and a skepticism towards the nature of their subjects, which I’m sure only a kid could muster.

My favorite piece of Khalifa’s was a little storm of crooking brush marks, all different colors, tearing apart a roughly done and slightly splattered black ground. The strokes looked mostly to be moving upwards, crowding away from an empty shoulder of black in the lower right corner. A troubled reprieve for the stuttering blooms of paint to appear more active against, this silent little swath of dark had the definite character of a smart ploy of composition. That it was in all likelihood not a smart ploy of composition — that it was instead the effect of a creative kid playing with paint more or less freely and eventually reaching a point with his canvas where things just simply felt finished or right — is of course the charm as well as the promise of art like Khalifa’s. Khalifa’s paintings (with some important qualifications) do the important thing that the art of children has often been hailed as doing. They show us what it is to create without preconceptions or interests other than the ones necessitated by our immediate experience, what it would be like to try to depict a world which you don’t know that you don’t know completely.

Though it’s seldom “better” than that of adult professionals, the art of children often seems more felt and authentically spontaneous, less considered and so less adulterated. In the period we’ve come to call modernity, art in general became historically distinct through its possession of a liberating but devolutional knowledge of itself as art. Almost categorically, the art of our epoch is reflexive art that’s aware of its history and paranoid about its style. The absence of this conflictive self-consciousness in the makings of children has therefore been a perennial source of inspiration for artists throughout the past two centuries. Artistic “genius,” as Baudelaire wrote famously in 1863, “is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.”

Or to put it a bit more precisely, we could say that the perceived naivety and spontaneity of the art of children stood for the modernists in antithetical relation to artistic style, a concept which necessarily signals rigidity. Style represented an ossification of the creative impulse into repetition and adherence, childishness that impulse’s hyper presence. A good artist might have hoped to channel the unknowing greenness of a child’s approach to creation as a means of bursting through artistic convention. They might, for instance, recapture with purpose that doleful black hollow in the corner of Khalifa’s canvas and fill it with the force of experience that comes from living a life.

The last quarter of the 20th century saw a dramatic inversion of the artistic problem of childishness versus style: childishness (or, more broadly, “naivety”) came steadily to be incorporated into style, losing its force as what once resisted stylishness. The most volatile single innovation of the arts of the 1970s and 1980s — that all styles were seen to be equally valid and that no one style was any longer “dominant” — unsettled the foundational separateness of the wittingly unwitting adult artist and the unwittingly witting child artist. Naivety ceased to be taken up as an operational principle and became adopted, with increasing frequency, as a stylistic mode on its own terms. The somewhat infamous “Bad Painting” exhibition at the New Museum in 1978 was exemplary, reveling in its willfully “bad-looking” objects’ collective suggestion that “the traditional means of valuing and validating works of art are useless.” Writing three years later of the new German wave of expressionist painting (which was not unrelated spiritually to the American “bad-painters”), the critic Donald Kuspit remarked that much of this work seemed to exhibit a “forced childlikeness.” “Getting down to cases,” wrote Kuspit, “one sees repeated an implicit allegiance to children’s drawing as the basis and ideal for art, as in the old Expressionists. Only now such drawing is calculated in its spontaneity, more inventive than improvised.” Childlike authenticity, in other words, was quickly losing its status as a methodology; it was in the process of becoming itself a style, incorporated in all its antagonism and authentic emotionality into the exact thing it was once seen to resist.

Since this reversal nearly 50 years ago, we’ve seen both a profusion and a normalization of styles which could well be called “childlike.” Improvised, spontaneous, ignorant, unsophisticated, tactically uncouth artworks are not only exceedingly common today but also fully expected and acceptable, and have been for quite some time. In fact, the show hung alongside Jdia-Bernhardt’s — in an old abandoned warehouse adjacent to Dragon, Crab, and Turtle’s more traditional gallery space — consisted of 10 or 12 large unstretched canvases by José Luis Vargas whose impulsive feel, random arrangements, and well-studied sloppiness struck me as being equal parts languidly uninspired and academically precise. The occasional similarities between these paintings and Khalifa’s were, I think, significant, and the differences between them seemed telling.

José Luis Vargas is a professional, adult artist who has studied at the Skowhegan School and the Royal College of Art. His paintings — not least of all those which populated his DCT show, “There’s No Way Back” — tend to have a knowing aspect of the unwitting masterpiece. In “No Way Back,” his pictures’ rough grounds barely contained a coterie of malproportioned creeps and cryptids slithering through hapless collage and minefields of splattered, dotting paint. “Naive” painting like Vargas’, which has been around as a style since the seventies, tends paradoxically to feel very coy and sophisticated, even academic. Although Vargas had taken pains to make his scenes look scooped directly from some collective unconscious, their would-be deceptive simplicity couldn’t help but come through as postmodern painterly smartness. Just like how Bougureau’s old saccharine subjects, for instance, look more like they sprang from the brush of a classicist than the mind of an ancient, Vargas’ mysterious, modeled images of unaccountably roving monsters and uncanny tropicalia have more the mark of the studio than the sideshow banners and touristy commercial pictures they’re clearly inspired by. Just one piece in the show — the only one colorless, which showed a speckled stump blasting from the picture plane straight into the painting’s gut, where it ramified onto an ambivalent array of obscured, distanced faces — managed to make something actually untapped and visceral out of its practiced sketchiness. But in fact, this piece was the least “simplistic” of the whole lot.

The rest, rather than true enigma, conveyed through their articulate imprecision almost an antipathy towards the medium of painting and our ways of apprehending it. One piece’s most prominent elements, scrawled onto an untouched white ground, were two stick-figure palm trees so precisely filling the canvas and framing the space between them as to harden the whole sparsely playful scene into something more lithic than spontaneously lithe. Another’s slug of a chimeric subject groped along towards the painting’s front (which it filled) with an incongruously stiffening exactitude. In these two canvases and almost all the rest, the brusque, basic iconography, as well as the steady roughness it was rendered through, seemed culled more from an online image search for “outsider art” than from any true engagement with those human sensations and experiences that are born outside of art. This made Vargas’ paintings seem, at least in terms of their style, incorrigibly and almost hermetically those of an “insider.”

My point in drawing out the comparison between Khalifa and Vargas isn’t to say that one has a good childishness and the other has a bad childishness, but rather that what is “childlike” in Vargas art (though he very well might not put it this way) is overdetermined and stylized in a way which goes against what was once artistically productive and promising about art made by “nonartists.” Vargas’ conscious intention may very well have been to make “The Unseen finally visible” (as he said in a statement about the show), but formally it’s all a bit arid and well-trod. Because Vargas takes as a priori stylistic determinants such unconscious forces of “the poetic imagination” (his words again) as naivety and impulsiveness, he fails to recognize that the promise of unsophistication is precisely how it runs counter to style.

When “naivety” in art referred to a methodology instead of a style, the happy, serious paintings of Khalifa Jdia-Bernhardt may have been able to serve as some kind of grand corrective against Vargas’ honed naivety. Khalifa’s clumsy colliding streaks might have made Vargas’ look a bit primly manic; their carelessly-placed daubs of paint could have made the adult’s own seem agonized and brainy. To an extent — and this extent, however asymptotically slim, is what’s indelible about the art of any kid, not least of all a kid with as much feel for his medium as Khalifa — the child’s paintings at DCT did resist their incorporation into rote stylistic terms. This seemed a remarkable if muddied testament to the old productive romanticism of many modern artists.

But when Khalifa’s paintings managed this, they did so only tenuously. Cheeky as it may have been, their very presence on DCT’s walls served as a marked reminder of the persistently unbounded rapacity of contemporary taste. What valuable morsels of separation there seemed to be between Khalifa’s paintings and any threadbare contemporary style they might resemble had nothing to do with the way they looked. Nothing about Khalifa’s paintings today, that is, appeared fresh or formally vigorous in the way they might have to a Klee or a Kandinsky — that dimension of their intrigue has been long exhausted. Perhaps, however, the conditions which preclude paintings like Khalifa’s from seeming stylistically noteworthy — the conditions which make them much more readily subjectable to theorization and judgment (not excluding my own in this review) than the art of children has likely ever been — are precisely the requisites for reinvigorating their historically vexing relationship to style itself. To make anything out of this observation, though, would be to approach art trepidatiously, respectfully, in a way which would probably exceed the strictures of critical language.

So I’ll end this review with a simple observation: José Luis Vargas’ paintings forced me to think, unsmiling; Khalifa Jdia-Bernhardt’s made me smile without thinking.

Del O’Brien is a critic and historian based in St. Louis, MO.