Featured image: Shara Hughes: On Edge, installation view. Two paintings hang on white walls in the gallery. The left square canvas features a red long shape off-center with surrounding colors of yellow, green, red, blue, and orange. The right canvas is a bit larger, and also square-shaped, with a big section of yellow color in the middle. Reds, blues, and greens surround the center-most shape. Photo by Dusty Kessler.

Shara Hughes’ painting Obstacles, from 2019, is nearly equal parts figure and foreground. In it, eight stumps (the obstacles) crowd out our view of a scuttling forest floor, which extends in daubs and thick scribbles of paint almost all the way to a smeared line of horizon in the canvas’s top eighth. Were their odd and activating conjuncts of color able to propel the eye any less thoroughly around the scene, these many playful blows to the surface would probably appear as satisfying as the random pointillisms of a spilled plate of dinner. Instead, each stocky efflorescence of yellow, green, brown, or red—even a furtive magenta peeking here or there from behind some darker blotch—takes on a very necessary, atomic character within the complex of paint. A downward yellow slash atop a white patch of untreated canvas slopes into a thrust of earthy green, itself lapsing towards a breath of thin misted red that falls suddenly into brown thrown back upwards to yellow by another jumping green. (Hughes doesn’t premix her colors.)

Up close these many rushes of color constitute a flattening array, and from fair distance they coalesce nicely into a childlike andamento. But follow any one of this forest floor’s chaotic themes for long and you’ll be stopped dead by a thing with an altogether different logic. Hughes’ jabs at the canvas that comprise her ground end abruptly at the boundary of each “obstacle”; here the hefty brush marks don’t become, but cede wholesale to her stumps’ downward smears. These dead trees are painted in a mode distinct from that of their setting. They’re discrete against the floor’s multiplicity; long and slow against its bustle; impressionist gradients against its expressionist confluences. Certain of the colors from without the trees are rhymed within them but in muddied smears instead of bursts. The forms look pulled from some different painting, color field streams plopped in a fauvist fancy. The eight runny obelisks—modeled altogether according to a definite, if not in itself noteworthy, principle of design—impose at their edges a rhythm of tensions and reliefs onto the chaotic unity behind them.

One’s gaze is jarred and lulled and jarred again, repeatedly, in the trip from canvas left to right, the vertically adamant stumps pulling the ungraded mess of paint up into perspective while collapsing backward through this ground they’ve been grafted onto. Through this series of simply posed but expertly articulated disjuncts, Hughes succeeds enormously in wrestling from her two chosen painterly idioms a respective necessity and overall compositional unity which neither alone could fully bear. The result for a viewer is a delight in the unlikely coming together of Hughes’ coloring and her design—a delight all the more deserved in that it’s been won through the deliberate arrangement of divergent, even conflicting, stylistic orders.

Obstacles currently hangs on a back wall of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, whereof the few dozen landscapes (mostly paintings, with several works on paper) comprising the solo exhibition On Edge is both the least brazen and the most accomplished. These two qualities, it seems, are closely related.

Hughes’ paintings in this show—her first major solo exhibition—offer up a unity of vision which is difficult to ascribe singularly either to a dearth of inspiration or to a concerted working out of artistic problems. In an achievement like Obstacles, it is clearly the latter. The series of slight but determinative stylistic juxtapositions between figure and ground reciprocally justify and are justified by each other. They are born from an impulse of Hughes’ to make pictures which hold together in spite of the unsubtle profusion of disparate techniques they’re constructed from. Conscious or not, this seems to be a welcome and very painterly approach to the idea that purely formal considerations, and an engagement with the problems which arise through them, can be definitive of both the appearance and the meaning of a work of art. Hughes’ stated approach to painting supports this: she begins by dallying on the canvas without aim, and after a worthy theme emerges reacts to it and its concomitants—now with a vague representational end in sight—through till the painting’s complete. The inherent tension in Hughes’ medium between figuration and materiality, which ostensibly forced abstraction to eat itself in the middle of the last century, emerges as an unlikely matrix for her to square some of the lessons of the last few decades of art: coy historicity, the parasitism of style, agnosticism with regard to form, medium unspecificity.

In Obstacles, the guileless apposition of distinct techniques serves smartly as a formal imperative, an intrinsic call to order, within the composition. It also provides an exaggerated excuse for Hughes to work through (and occasionally to undermine) the basic grammars of two-dimensional art. Hughes’ paintings, at their best, appear thus like wrestlings with the aesthetic plurality in the name of artistic singularity.

Hughes is prone, however, to working herself into corners out of which she has no real choice but to explode. This is likely as much a result of her volatile method as it is of the unfortunate premium we tend to place on the immediate or surface effects of visual artworks—especially paintings—today. Often the tensions in her works between passages of varying stylistic orders, which is an almost ubiquitous trait, seem to be condoned by nothing other than the raw and immediate response they produce. This is, of course, insufficient. (The friend who came with me to see the show noted almost immediately upon walking into the gallery that the many paintings crowding CAMSTL’s walls looked much better as a dazzling and quickly-grasped array than as individual works.) Considering that Hughes is a landscapist painting within the same half-century as Fredric Jameson’s been writing, it’s tough not to accuse many of her dissonant, denatured pictures of conforming to some kind of vulgar sublime: they take their brashness and surreality as the ends of, rather than a means to, intense emotional response.

In a piece like Peep Show, for instance, the maelstrom of colors, textures, densities, depths, and warring lines of sight fails to constitute much more than a dizzying optical effect. Fraying buds of yellow, green, red, and blue, which look like pancaked crafting pom-poms melted onto the painting’s surface, make up a portal through which a polychrome cascade falls on some rocks and roots. Additional layers of border, which may exist before or behind the framed scene, glom onto the blooming limen and trouble its credibility as a spatial marker. Two unaccountable streaked black triangles in the bottom corners corrupt our sense of perspective further. While the crop of slick stones which cuts from the canvas’s bottom center to the border’s middle right does manage to intervene commandingly on the picture’s disruptive order, providing a solid compositional foundation for the play this jetty recedes into, even this success of arrangement becomes lost among the painting’s manifold less-justified flattenings and distortions. It’s not the work’s overwhelming busyness, however, which dilutes the value of its undeniable adventurousness. Rather it is the inability of this busyness to assert itself as functionally necessary within the composition. None of the many disjunctions reflect on each other or refract the painting’s overall design: they simply exist, in ambivalent unison, on a painted surface whose toyings with perception and placement only emphasize its trite literalness.

In many, if not most, of the works in On Edge, Hughes’ setting up of tensions appears all too deliberate, like an affectation rather than a solution. It becomes a manner of making rather than a method of working. This loses sight of the fact that the opposition and resolution of forms or concepts is, to an extent, endemic to all art; the task of an artist should be to determine the types of tensions germane to their mode of making and to instrumentalize them in service of attaining a less specific type of finality in their work. A failure to do this is the failure of many of Hughes’ “oculus” works, like Peep Show. Generally, their deliberately contrived relationships between the painted border and occluded scene find little excuse in the occasional dialogue this fosters between, say, a color or a shape recurrent in both. Likewise, Hughes’ “mirror” pieces, in which she uses the natural doublings of reflection to explore the representational parameters of her combinatory style, typically prioritize the rote execution of the conceit of reflection over its formal implications (which could be significant).

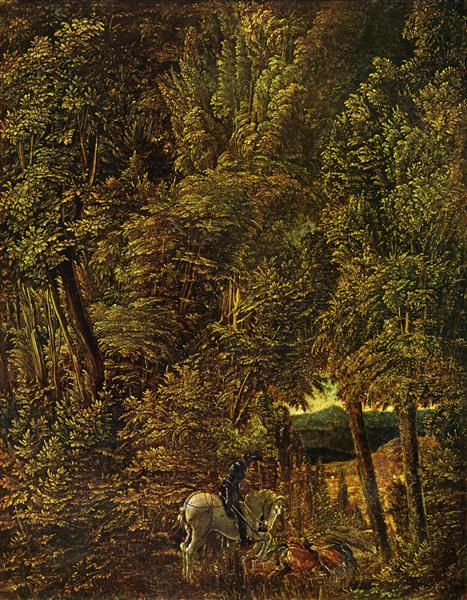

The merit of these somewhat abundant less successful works, at least for the critic, is their clear indication of the remarkable fitness of Hughes’ recent work (she came to these constructions from Matisse-like interiors less than a decade ago) within the long tradition of landscape painting in the West, somewhat surprising for paintings as flippant, fresh, and willfully naive as these tend to be. (To be clear, I use these adjectives with endearment: Hughes is at her best when the spontaneous character of her pictures comes to express itself as a sort of rhythmic thoughtfulness.) Many of her topographical features, for instance, seem pulled from the fervid settings of the Northern masters, and her general subordination of the facts of a natural scene to the psychological experience of it finds clear precedent in other 16th-century landscapists, as well as much later in post-impressionism. Her almost spiritual, jubilant confusion of light and color, as well as her multiplex but determinative strength of line, finds further antecedent in the latter. This context, above all, helps clarify an important point about Hughes’ own work: that within this genre of landscape painting which she, with whatever recalcitrance, inherits, the success of a picture depends not on its capacity to reproduce the same sense of wonder or contemplative amazement which we might derive from being in nature, but rather it depends on its incorporation of such emotional effects, through an artist’s will, into a pictorial scheme which is derived from but moves beyond them.

On this point, I’d like to return briefly to Obstacles. This painting, above all, demonstrates the elegant simplicity of the engine which powers Hughes’ paintings almost ubiquitously: vision is arrested by a passage of some style or another propounded to a point of near collapse, whereupon a theme entirely dissimilar in medium or technique is interposed, throwing the act of looking into a stumbling disarray which only finds its footing again as these themes synthesize towards the articulation of the picture’s broader order. In Obstacles, where this process is most thoughtfully expressed, each tree casts a shadow on the ground behind it.

In these, the downward smears which make up the stumps have given way to overlapping strokes of a broad, deep green, each one and all together firmer and more assured than the colorful spatter they’re cast onto by a sun hidden above the top right corner of the frame. The trees, it seems, are exposing to the viewer their darkened backs, below which the sun is speckling the ground in countless quick swells of color. As you follow the trees upwards, then, towards a middle distance which becomes, once the dappling ends, its own broad smear of featherlight green, you begin to realize that the same optical logic which makes the tree-shadows meld the slur of the stumps and the ground’s splatter has caused this protracting wash of paint, which heaves up to the simple outlines of unarticulated, distant mountains. Whatever world it is that Hughes has created here, it’s one furnished with an order so strange and thoroughly realized as to have a consistent way in which its sun, striking the ground, would set colors flurrying till they meet the umbra and begin blending towards a slow upward smudge.

Shara Hughes’ On Edge will be on view at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis through February 27, 2022.

Del O’Brien is a critic and historian based in St. Louis, MO.