Featured Image: Nico Sardina, Here We Are All Up In Arms (Ultimate Henry’s Comfort Zone PT 2), 2021. A pair of documentation photos where the left image shows a sculpture of a house, multi-colored and slightly askew. The house is made out of different fabrics with many patterns and colors. The image at right shows a close up of the back of the house where a soft body-like form occupies a cavity in the house. Photos by Michelle Caron-Pawlowsky.

This interview is the first in a series with each of the current fellows at the Emerging Curators Institute (ECI), a Twin Cities-based organization that supports emerging curators through a year-long fellowship program that incorporates mentorship-based learning, professional development, and financial support. ECI is the first organization of its kind in the Twin Cities region and provides curatorial opportunities to Minnesota-based curators that are otherwise hard to come by. ECI supports four curators each year and is currently in its second fellowship cycle. Operating within the Minnesota arts community, ECI connects its fellows with local curators, galleries, artists, and other field professionals who support in the development and production of an exhibition or curatorial project. This first interview is with Kehayr Brown-Ransaw, a Minneapolis-based interdisciplinary artist, educator, and curator. Click here to view the other interviews in this series.

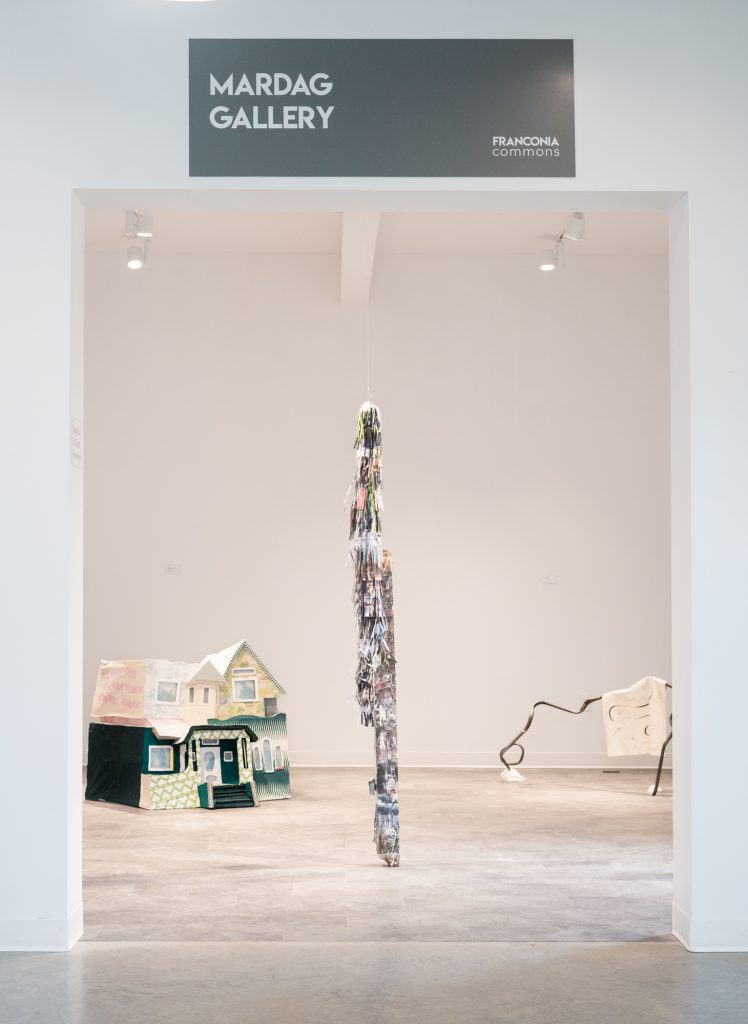

A committed and spirited individual, it was easy to fall into conversation with Kehayr and move through many topics, from the hardships of moving away from home to his deep love for the 1975 musical/film The Wiz. Kehayr’s approach to curation emphasizes care and honesty; he views his role as curator as someone who uncovers and reveals the stories inherent within a work of art and contextualizes these stories within the larger conversations of an exhibition. Kehayr’s exhibition, After, Other, and Before, brings together a group of artists – Nico Sardina, Beau Tate, Timothy Manalo, and Kieran Myles-Andrés Tverbakk – who explore shifting definitions and manifestations of home in relation to their identities as people of color who carry the marker of “other”. In the catalogue essay for the show, Kehayr writes: “Culture observes its contents through a singular lens, filtering perceptions and concepts through the normalizing experience, which determines what is good and worthwhile, and what is otherwise foreign and dangerous. After, Other, and Before disrupts a settler colonial identity and ‘other’ identity marker placed on People of color. Through works by diasporic artists…the exhibition confronts, challenges, reconciles, and recontextualizes what it means to be ‘other.’”

After, Other, and Before is currently on view at the Mardag Gallery at Franconia Sculpture Park (Shafer, MN) until the end of the year.

Ian Hanesworth: Could you start by telling me and our readers a little bit about yourself, your artistic and curatorial practice?

Kehayr Brown-Ransaw: I am a Minneapolis-based fiber artist, curator, and educator. My artistic practice is currently in an in-between space where it’s kind of moving away from an exploration and investigation into my family, and how I fit into that, and into a more collective and communal narrative around family. Part of that is because I live in Minnesota and I’m the only one from my family that is here. The rest of my family is in Wisconsin or other states. It’s been interesting to find a new family here in the Twin Cities and my curatorial practice has been very much influenced by that. As a curator, I want to work with people who are typically underrepresented in gallery spaces, but who are also investigating different ways of existing and presenting themselves, their work and ideas. I think one of the things that I value in the artists that I’ve gotten to work with so far is that their work isn’t saying so much, but just enough.

IH: Over the past year you’ve been a fellow of the Emerging Curators Institute. What has that program been like for you? What are the structure or goals of the program and what has the opportunity meant to you as an artist and emerging curator?

KBR: I really wanted to apply to the ECI fellowship program because I have this natural want and inclination to lead and organize, and I think being able to do that with artists is super valuable, but I wasn’t sure where to start. I had questions like, how do you actually become a curator without just kind of falling into that? Or how do you get that experience? And this was just one way that I saw to get that experience without having to go back to school and go through a curatorial studies program where you just learn theories about art and how to present it and how to curate. ECI’s fellowship program is primarily a mentorship-based structure. Each fellow is assigned to one mentor who we work with over the course of the program. My mentor is Casey Riley. She is a curator and the head of the department of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. We also have monthly fellowship meetings where we learn about different modes of curating, the kinds of shows and exhibitions that exist, all the different ways to write, talk, and think about art. And then also just like, how do you do it? How do you get jobs as a curator, where do you look for them, how do you look for them, and, also, how to value yourself? I think emerging can be a really intimidating label for some people, or I feel like it’s really easy for employers to devalue your experience and knowledge. But the folks at ECI have been like “yeah, you’re brand new to this, but like, these are skills that you have now and you can learn by just kind of doing it.” That’s what my experience and my takeaway has been. We’re also paired with another fellow to be a support for each other. And I think this year has been really weird and interesting just because of the pandemic and having meetings over zoom. It’s just been a really interesting structure this year, but it’s been great.

IH: What has it been like to be a part of this cohort of emerging curators, and cultivating a mentor relationship during the pandemic? What has that community meant to you?

KBR: It’s definitely been different than what I expected. I felt like initially going into it I was maybe a little afraid or guarded to be overly friendly or interested in the other fellows because it was like, well, we didn’t know when, or if we’ll be able to ever see each other in person. But now that I’ve gotten closer with my cohort, I would love to work with any one of them again in the same or in a different capacity. I want to be able to keep following and supporting them and their work. There’s been challenging aspects of this program and I think going through it together has made it feel different and not so difficult.

IH: You and I went to school together at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design so I’m very familiar with your work and visual arts practice. Until recently, your practice has been grounded in making, in being a sculptor, a printmaker, a fiber and textile artist. I’m curious what it’s been like for you to move into this realm of curation?

KBR: Yeah, it’s been interesting for sure. I feel like I approach curating in the same way that I approach art making. The way that the show has come together has felt very natural. But when I was initially doing research and looking into artists that I wanted to work with, I wasn’t super satisfied with what I was finding. But I just let myself continue to be unsatisfied and eventually then I found something that was entirely different and it just clicked. It made sense. And it was like, this is the work I want to show, this is what the show has to be about. It just made sense to me to work in that way. And I feel like it is really about building a relationship of care and understanding of the works and the exhibition itself that has made me feel really proud of what it’s becoming, which is very similar to how I work with my own pieces. I just let them exist as they need to exist.

IH: I really like that idea of cultivating a relationship of care for the artwork that you’re curating. When I think about curation, that’s not necessarily the first thing I think of, but it’s a really compassionate, I think, way to approach curation. There’s a gentleness to it and I see those same threads in your work.

KBR: I want the work and the show to feel really honest in a way where I don’t want to present works to create a narrative that isn’t already there. It’s something that I feel good about.

IH: The Emerging Curators Institute fellowship culminates in an exhibition, and yours is at the Mardag Gallery at Franconia Sculpture Park in Shafer, MN this fall.

KBR: Yeah, my exhibition After, Other, and Before opened September 25th and runs through December 31st.

IH: Can you tell me a little bit about the artists you’re working with for this exhibition? How you came to work with them and what it was like to build a relationship between artist and curator?

KBR: The artists that I’m working with are Timothy Manalo, Beau Tate, Nico Sardina, and Kieran Myles-Andrés Tverbakk. Timothy is a Toronto-based sculpture artist and was the first artist that I selected for the show. His work is really interesting to me just in terms of how it presents so much information and so little at the same time. He’s discussing his experiences as a child of immigrants and navigating how his culture at home is very different than his culture in school or the broader culture around him. His piece Ancestral Floods came across my Instagram feed and that was the first piece that I was like, “I’m in love with this, I’m in love with this work.” And it was what made me understand what the show was supposed to be. Beau Tate is a Minneapolis-based installation and video artist. Beau and I actually went to high school together, and with my conceptual focus on home and family, it made sense to me to include their work, especially alongside Timothy’s. Nico is also based in Minneapolis and Kieran is based in Minneapolis and currently attending graduate school in Arkansas. Nico and Kieran’s work, and all four of them really, present investigations of how they exist within their own bodies and memories and move through their day-to-day spaces as people who are nonwhite and heavily influenced by the immigrant cultures within their lives. Selecting artists was really hard. I had a long list that I just kind of sat with for a long time. Compared to some of the other fellows, I think I selected my artists pretty late because it took so much for me to feel comfortable but I’m really happy with the artists that I chose.

IH: What ideas, themes, traditions, or sensibilities drove you in your process of curating work for this exhibition?

KBR: One of the things that really interests me is the idea of time. I think time is non-linear, but we describe it that way and when we have to map out time, we map it linearly. I don’t think it really exists like that. I mean, you know, it’s also not real (haha). I was also thinking about space and home, so home, space, and time are the three big words that informed my conceptual framework for the show. I specifically wanted to work with POC artists, and thinking about being a person of color and thinking about time can be really violent. I wanted to understand through these works, how that violence informs this very sensitive topic of home and space. Being all North American-based artists, there’s definitely a settler-colonialist marker placed on anyone living here that isn’t indigenous, but I think it’s an interesting relationship that you then have to that and to the land that you’re occupying.

IH: What are the connections you draw between time, violence, and POC identities?

KBR: I think the major, and obvious, connections of time and violence as it relates to people of color are related to colonialism. The title of the show After, Other, and Before is an attempt to acknowledge time as a history and future and renaming the present as “other.” I think this renaming gives space for the present as something different and special in the way we measure time. It is never an exact point, by the time you’ve acknowledged it, it’s already gone. I think people of color exist in a similar way, constantly evolving and adapting to our circumstances. As people of color, we don’t get to exist pre-colonization, and what does paints an image of archaic peoples and “primitivism”. But the during and after is riddled with so much loss and trauma that it only makes sense to look towards a future. I find that so many questions of the future come with an undertone and recognition of systemic problems that we still face in our day-to-day lives. I end my essay with “something still drives us to fix a past to find a future,” because I believe that in building a better after, we atone and reconcile the pain and trauma endured by our before.

IH: I love the way you talk about time, it’s non-linearity and relation to healing, and the way you situate the present within the idea of otherness. In the catalog essay for the exhibition and in our previous conversations, you’ve referenced The Wizard of Oz and the 1975 Broadway musical and film The Wiz. I’m wondering if you could talk about what these musicals and films mean to you and to the themes of this exhibition?

KBR: “There’s no place like home” is such a pervasive phrase within popular culture, but I think it can be a really insensitive phrase as well. Cause what happens when home is taken away from you? Or you can no longer access it safely? Most people love the original Wizard of Oz, but I saw The Wiz before I saw The Wizard of Oz, and to me personally, I just didn’t like The Wizard of Oz. I felt like that version of Dorothy was very harmful to a lot of people and it just didn’t make sense to me. It was just like, if she’s so unhappy, why does she desire to get back there? Why can’t she desire more for herself and why can’t she have wants or needs beyond her small farm in Kansas? And I think that The Wiz, which ultimately is just a queering of The Wizard of Oz, really puts that into perspective that you can want more for yourself and you can leave. It’s ok to leave. Home is not necessarily tied to a physical space. It’s also not necessarily tied to the people around you either. Home can be within yourself. And as far as the show is concerned, I really wanted to represent that and explore all the ways that home can exist for different people and communities, specifically POC. I think I found a deeper understanding of home through these artists’ works.

IH: How do you see the idea of home being represented or dissected or disrupted in the works you’ve curated?

KBR: I would say each artist presents an understanding of home in relationship to space and people through somewhat of a metaphysical lens. Timothy really identifies home within people and within family, and Beau’s identifying home with self and the comfort and turmoil that you can feel within your own body as a home space. I think that Nico and Kieran are doing a combination of the two, where their work is identifying a physical home space and a comfort that is connected to that space, connected to memories, connected to the people around them, but understanding that home is still within their own person and their own experiences. Nico is specifically identifying home within others, within their own experiences and the experiences of those around them, and creating a more empathetic relationship to the space of home.

IH: In your catalog essay you write about a pivotal moment in The Wiz, a moment where Dorothy grapples with her evolving understanding of home. You write “She understands that she has changed and that her desire for more and a different life are okay. She learns that her family and the things she loves about home, don’t bind her to a place. It gives the audience a sense of security and self-discovery and liberation.” How do you and the artists grapple with the shifting definitions of home and the relationship between home and security and liberation?

KBR: I think it’s very interesting just in terms of the fact that myself and several of the artists have moved to Minneapolis from our hometowns. In working with Nico, we’ve had conversations about how when we’re in Minneapolis and refer to home, it is always in reference to the city that we grew up in. But when we’re in our hometowns and reference home, it can be either that city or Minneapolis. Home isn’t singular. And at least for me it isn’t. I’ve been back to Milwaukee so infrequently that I do feel very at home in Minneapolis. There are days where I wake up and forget that I’m in an entirely different city and my mom isn’t just down the street. Some days it’s really hard to be so far from family, but there are other days where it feels really nice to know that I was able to move to a different city and find community and find things that make me feel happy. The song “Home”, from The Wiz, is one of my favorite songs. And when I’m thinking about specific moments in the song, I’m very sensitive to the way that our departure or migration affects the people that we care about. Diana Ross’s character is discovering that if she were to leave, it could hurt these people, but she realizes that it’s okay because like we still have each other within our hearts and we carry home within ourselves. Within a lot of POC communities, it is a very big deal to move away from your family. And like for some families it can be incredibly insulting to just move out of your parents’ house. And I think getting to a point where you feel comfortable with that and feel like it won’t kill you, it’s really freeing. I’ve recently gotten comfortable with the idea that if I keep curating and wanting to curate, I could end up not living in Minneapolis. And that was something that was really hard for me at first. Just the idea of moving somewhere else and leaving all my friends and leaving everything, you know, it’s like, how do you just do that? But I’m realizing that it would be okay, and that my own understanding of home is going to continue shifting and changing throughout my lifetime.

Ian Hanesworth is a non-binary artist, writer, and farmer from Winona, MN (occupied Dakota land). Their work and research centers on ideas of deep ecology, plant medicine, and environmental stewardship, traversing mediums of textiles, printmaking and agriculture. Their writing has been published on MnArtists, a platform of the Walker Art Center, and in the book Slow Spatial Research: Chronicles of Radical Affection, edited by Carolyn F. Strauss. In their free time, Ian tends a dye garden, preserves farm veggies, and talks to rivers.