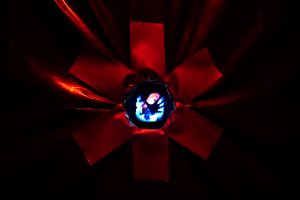

Featured Image: Foreground (R to L): “Gatekeeper” and “(Wake Up Every Morning)”; Midground: “A House Divided;” Background: Inkjet Print. Courtesy of The Kranzberg Arts Foundation.

“The objects of art jabbed the viewer low in the abdomen, squeezed his heart, pricked his mind. It communicated with those blind to its artistic excellence, as well as with those who saw.”

Noah Purifoy, Junk Art: 66 Signs of Neon

The twenty or so impassioned sculptures in Ronald Young’s solo exhibition The Prevalence of Ritual—on view for the summer season at The Kranzberg Arts Center Gallery in St. Louis, where Young lives and works—crack and heave with the blight of the city that birthed them. Invariably, their intensity is arresting, and mostly it’s to good artistic effect.

Six large inkjet prints of gutted brick buildings, which hang along the gallery’s perimeter, provide clear context. In one of these photos, the contour of a halved and roofless structure cuts a seizing figure against the sky’s subtler ground. In another, the grain of an old door marbles nicely behind its firm brick frame. All six photographs are unpeopled and tightly cropped. Though too pedantic to be quite convincing as pictures in themselves, they still convey in their burned-out subjects a decided aspect—which Young does his best to graft onto his sculptures—of the picturesque. In their close attentiveness to the contradictory visual delights of, say, a shattered window or a crumbling home, the photographs speak to what seems to be Young’s preoccupying question as an artist: How does one make the forms not simply of a city itself, but specifically of its disrepair, into artistic material?

The obvious (and, at this point, pretty well-trod) answer to this question, which Young manages to appropriate, is: By making stuff out of the trash strewn about it. Young’s idiom is assemblage, that old modernist attempt at a plastic art that would be something other than painting or sculpture or architecture. Out of chucked boards, shards, planks, and trinkets collected from the streets of St. Louis, Young fashions objects which, it would seem, attempt to translate the aleatory, discomfiting beauty of post-industry’s outcomes into a stark and abstract sculptural language. (It should be noted that our inclination today to classify artworks like Young’s as a specific type of sculpture, rather than ‘assemblage’ as such, speaks to a weakness in one noteworthy element of the genre’s early pretensions. Duchamp’s readymades and other Dada constructions wanted to demystify aesthetic experience by flinging so much unrarefied stuff into art’s stodgy purview. The general acceptance, a century later, of refuse as a wholly valid sculptural material seems to suggest durability, against the Dadaists’ niggling, of artistic imagination.) Young’s rough-hewn objects, especially in their frantic quality and vague inflections of African forms, betray a clear technical affinity to a host of modernist forebears. Their loose but definitive conceptual program, however, inherits much less from Schwitters or Surrealism than it does from the so-called “junk artists” of the 60s and their descendants.

It was these artists—Noah Purifoy and Judson Powell, somewhat apocryphally but now canonically—who introduced a subtle, ultimately taxing shift into the practice and conception of aggregative sculpture half a century ago. Prior to this intervention, meaning in assemblage was generated through a pervasive functional ambivalence towards the art object’s ingredients in themselves, however jarring they might have been. This was accomplished through a subordination of the artistic material to the imaginative content of the work. Artists privileged the formal or symbolic relationships which could be stimulated between their collected materials, each of whose aesthetic potentiality tended only to be realized, if at all, in and as constituents of the finished piece. Meaning was consistently taken to be not only immanent in the assembled artwork, but also fully traceable to its fulfillment—that is, not existing in an aesthetic sense prior to the conjuring stuff that artists do. Matter and content comprised very different and also stratified, registers. The “incongruous elements” of assemblage, as Tristan Tzara reflected of Dada’s surprising and often ‘low’ materials, were “transformed into an unexpected, homogeneous cohesion as soon as they [took their] place in a newly created ensemble.”

For the junk artists, such transformations were still critical, of course, but they became no longer paramount. As they saw it, their sculptures (and here, perhaps paradoxically, these seem unequivocal to have become ‘sculptures’ in the assemblage mode, rather than ‘assemblages’) were comprised not of derelict objects in want of the artist’s homogenizing touch—they were built up, to borrow Judson Powell’s pretty phrase, from so many glinting “jewels in the sun.” This is how, some years after the fact, Powell recalled the oddly pleasing look of all the shrapnel lining LA’s streets as he and Purifoy ambled through them in the wake of 1965’s Watts Riots. Though the sculptures they made from the stuff they then collected saw only a small surge of interest at the time — their inaugural “junk art” exhibition, 66 Signs of Neon, traveled modestly for a few years, and its artists were then mostly forgotten until a large LACMA exhibition in 2015 — the actual influence of their approach to assemblage was quite exceeded by its exemplarity. The junk artists articulated best and earliest several notions about the technics of meaning in assemblage, departing from the broadly Modernist conception glossed above, which would come to undergird much subsequent practice.

For them, the raw materials of aggregative sculpture contained symbolic meanings and aesthetic significance which anteceded their interpolation into and realization through the finished work; these significances interacted consistently with that of the total artwork so as to alter the terms of aesthetic effect and understanding in the viewer; and it, therefore, became the artist’s duty not simply to arrange but to shepherd or wrangle their chosen “artifacts” (no longer simply “elements,” as Tzara had had it) into an affecting sculptural whole. If the earlier approach to assemblage had sought to unsettle inherited cultural dispositions towards the artwork by introducing ostensibly unsuitable materials, this later one sought additionally to gild or aggrandize, through the artistic process, objects seen to be at once aesthetically significant and extra-artistic. Assemblage artists since this turn have therefore had to grapple, in the execution of their sculptures, with the idea not merely that the completed work confers aesthetic and semantic significance onto its constitutive objects unidirectionally, but that each individual component of an aggregative sculpture can contain near-sufficient formal qualities and layers of significant content which bear multi-directionally on the sculpture’s totality. This drastic expansion of assemblage’s signifying field has been the source of much imaginative potential for artists, but also of a challenging bind placed on the terms of their achievement.

It is necessary to point out, in our moment of vibrant matters and new materialisms, that the junk artists’ (and other related or subsequent assemblers’) notion that their sculptural materials were suffused with cultural meaning and an immanent type of beauty did not amount to the discovery of an absolute principle. Rather, it was an artistic affectation with specific implications for sculptors who worked—and continue today to work—with found materials. “If junk art in general,” wrote Purifoy in the catalog for the 66 Signs exhibition, “enable[s] us only to see and love the many simple things which previously escaped the eye, then we miss the point. For we here experience mere sensation, leaving us in time precisely where we were, being but not becoming.” The final consideration for the success of an assemblage sculpture was still a particularized version of the general artistic sort of transformation which pertained to earlier assemblage works exaggeratedly and all sculpture surreptitiously: the passage at the hands of an artist of ordinary materials into imaginative matter. What the post-sixties elaboration of assemblage has wrought, however, is an intensification of the affective potential of this process at every level; the terms of the genre today are much more volatile than they were at its outset. Uncoupled from any imperative to represent because its matter is taken to be intrinsically meaningful, the form of much assemblage over the past half-century has been given over to a rogue and affrontive impressionism. This is less abstraction than it is a sidelong sort of figuration, where what’s figured tends to be something untenable like a theoretical concept or a political disposition. This has provided for the possibility of an apotheosis of the assemblage method in its purest form, but also for the danger of an overreliance on the raw meaningfulness of a sculpture’s materials to the detriment of overall quality and intrinsic completeness.

In the work of Ronald Young, this challenge attempts to resolve itself in an ebb towards acheiropoesis or spontaneous generation. His sculptures are at their best when they appear to have been plucked as such and miraculously from a half-filled dumpster or an abandoned job site, rather than made by the hands of an artist. In the stark and lyrical “Everything&Nothing,” one of the show’s best, three obstinately vertical groupings jut up from a squat black base. One consists of a twisting metal rod jabbed unstably through the base of a block of light wood. Into this—a common theme throughout the show—are hammered a crooked storm of rusting nails in the manner of Congolese nkisi nkondi power figures. On this totem’s side, two salvaged two-by-four pieces, chipping white with paint, are combined in a terse right angle; the straightness of one sets off the curving gut of the other.

Next to this arrangement is a much shorter but similarly flaking lone wood cutting, whose top has been lopped at forty-five degrees. Set parallel to the middle piece, this small component slopes down harshly in the opposite direction of its companion’s softer grade, coaxing a slight but startling visual disjunct. From much higher up, like flies in a watchtower, the nails invest this quiet scene with a frantic movement which their wrought-iron support dissipates at excruciating length into the plinth below. But this all happens at a cryptic remove. The L-shape of the work’s midsection at once encloses the smaller wood piece and excludes the tower, lending each of these formal affinities a narrative flair that is at once maddeningly obscure. This impenetrability of the scene—and the reinvention that its components seem to undergo—serves the sculpture’s end well: the piece’s logic has the appearance of happenstance, as if Young had petrified the positions of some especially intriguing debris he’d seen just off the sidewalk. In moments like these, Young’s stated goal of “embod[ying] the collective consciousness of generations of black people” (which he does by bringing to artistic life the detritus of what his work suggests are Black environments) lends itself most successfully to an aesthetic program. His art breathes an organicism—a spontaneity and a naturalness—which thrives on the dense suggestiveness of even his most unremarkable materials.

The most glaring weakness in “Everything&Nothing,” however, is one that haunts many of the works in Prevalence of Ritual: its one-dimensionality or lack of consistent dynamism. From a good number of perspectives, that is, all of what is said above—and potentially more—holds true; from several others, these are simply pieces of trash glued to a board. For “Everything&Nothing,” this is a minor issue, but for pieces like “No Time to Rest” or “Mojos Mojo,” which only seem to work from dead-on, it’s damning. Because of this their sometimes-titillating array of joints and hollows, even from the perspectives which suit them best, start to seem perfunctory or forced. This is catastrophic for sculptures whose success seems so heavily reliant on their simulation of autogenesis.

An opposite problem affects some of Young’s larger and denser works, though not nearly as fatally. The show has as its centerpiece two works set behind a brick enclosure: “GateKeeper” and “(Wake Up Every Morning) Tied to the Post.” The former has charred wood, metal stakes, frayed rope, and nails arranged like a rearing sawhorse; the latter is a paroxysm. Both sculptures contain a glut of stuff—tensile manes and distending metal and knots and junctures. Their shared busyness, rather than affecting an analogous rush in the viewer, detracts from the sculpture’s ultimate, aleatory unity. A toy car and broken broom in “Post,” and “GateKeeper’s” uncharacteristic lapse into figuration, read as last-ditched attempts to provide a cohesion which the bald arrangement of materials doesn’t quite achieve.

Better executed in their formal complexity are the odd and angular “A House Divided” and “Justice 4 Just Us.” In each of these—which I took as a sort of diptych—, the vertical stab of a sorry plank is set off and softened by weights and surges from elsewhere in the sculpture. Two bricks in “Justice” sink the piece from its side while a separate scratch of wood wrests the upright plank’s hold crosswise; the effect is dizzying. In “A House Divided,” fire-blackened beams stretch upward like fists, though a slung chain to the side offsets this movement slightly but assuredly downwards. A lone nail, too, driven into the top of one of the boards, parodies their vertical movement and acts, once it’s noticed, like a magnet for the piece’s significant vitality. It is perhaps the best-placed and smartest single element in the entire show.

The same slight lack of dynamism that hindered “Everything&Nothing,” however, also troubles these two excellent works: from some angles all their energy seems to flatten and dilute, which undercuts the sensation of fully realized execution from even the best vantage. Young seems to have made recourse to unelaborated ornamentation, in the form of less-skillfully hammered nails and some extraneous chains. This sometimes halting success of “A House Divided” and “Justice 4 Just U”s is I think only—but in this case almost totally—remedied to complete achievement in Strange Fruit, by far the show’s best piece.

All the cryptic meaning and physical presence, the immemorial spiritualism and enveloping sense of a place and its people that tends to be simply implied by many of the works in The Prevalence of Ritual, is suffused through each crack and crevice of this piece. In it, the productive tension between the form of its constitutive objects (and their imbued meanings) and the overall form of the composition (and its) is most precisely and powerfully rendered.

Two irregular but congruent blocks of wood, charred black and shaped roughly like lowercase b’s or d’s, dangle from the hook of a curved plant hanger. The crook of one descends lightly from the curve of the other like an upturned pieta, the space between their mirrored bellies blasted to shards by nails. On every uneven side, in fact, these nails protrude in a pained array that makes the act of looking a sharp and sputtering one. Any focus lent to one discrete part of the sculpture is inevitably diffracted by these nails onto the fractal whole (and here Young realizes, as few artists have, how to make nkisi nkondi into a meaningful formal imperative) which in turn fractures and redisperses the gaze onto some untenable part. By these means, Young has reached a rare accomplishment: an assemblage sculpture that consciously integrates the meaningfulness of individual materials and the total artwork at every level of the finished work. This piece—and, to a less even extent, several of the others in Prevalence of Ritual—demonstrates a distinct potential for the continued vitality of assemblage as a sculptural approach.

Del O’Brien is a critic and historian based in St. Louis, MO.