Featured image: Mehran Salari, Untitled, 2017. Monoprint and pencil and pen, 40×40 cm. A black and white image that is largely abstract with a group of organic shapes. Image courtesy of Didaar Art Collective.

Last Spring, Didaar Art Collective, a cooperative group of Iranian artists based in Chicago, organized a group show titled Space: Chapter One at Oliva Gallery. The exhibition was on display from April 9 to May 8, 2021, and featured drawings and printmaking by twenty-nine emerging Iranian artists. Toward the end of the lockdown, I visited the exhibition. I was yearning for a moment of reflection on the intricacies of our spatial bound beyond the insipid private experience in front of my laptop screen. This was an experience that I had greatly missed, and the exhibition, beyond its visualizations of space and possibilities, was uniquely positioned to give insight into the ongoing contested-over space in Iran.

It was refreshing to see how these artists work around the difficulties of the current moment while standing their ground during a time of mass oppression, political strife, and economic crisis. In their works, the artist’s contest the dispossession of space and its subsequent distortion by a tyrannical government as well as an unfettered market. Thus, it was not a surprise to find that these works imagine utopia collapsing into dystopia. In the last decade, Iran has witnessed an incredible rise in the wealth gap and mainly human-caused environmental disasters. The cities have grown more segregated along class lines while simultaneously the rural areas have been robbed of their livelihood due to ongoing plunder of resources, leaving behind the locals with resource shortages and unemployment, forcing them to migrate from their ancestral lands. Resistance, of course, carries on. In this context, contesting space is a social and political act.

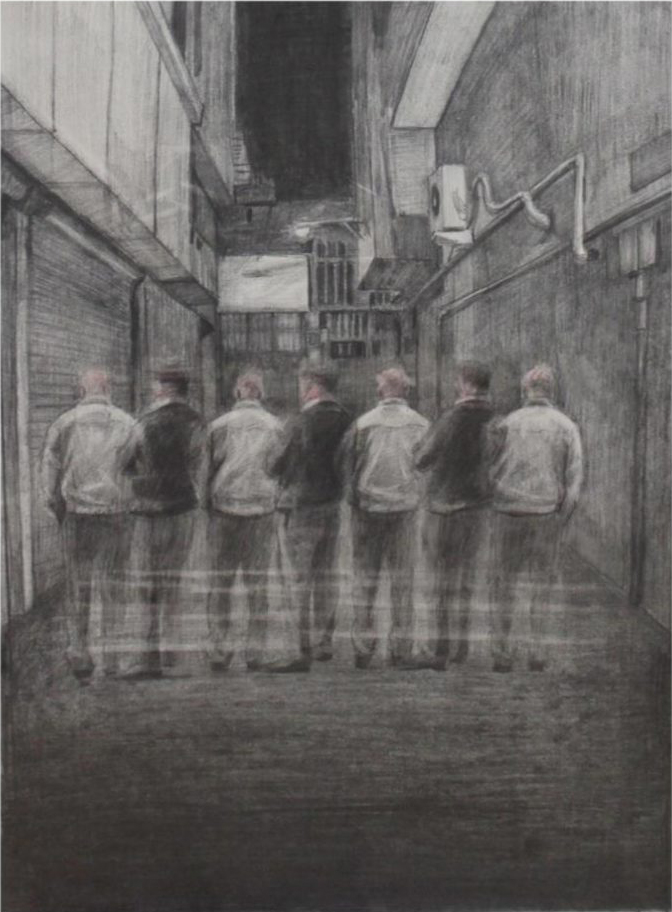

The works I will mention constitute only a small handful of the remarkable works of art in the exhibition visitors could explore. In Mehran Salari’s Untitled (2017), the viewer is confronted with gray silhouettes of what at first sight may look like mounds. Coming from Kerman, a province in the southeast of Iran, Salari captures a sense of dwelling in an area where people traditionally construct Kapars, which are temporary shelters made from local plants and trees (e.g., Tamarix and palm trees). In the foreground, Kapars appear intimately interwoven with one another, forming what could be a centuries-old fossilized mound—a familiar landscape reminiscent of tells or tels (the remnants of ancient cities in Mesopotamia)—on the verge of extinction. If Salari creates a work that registers a landscape of vanishing Kapars, then artist Mina Ghahremani suspends the viewer’s expectations in a stalemate. In Ghahremani’s piece The Path Narrows from the Left (2020), a group of men, seen from behind in a similar pose to the Romantic Rückenfigur, stand in a dead-end alley seemingly in downtown Tehran. Like pawns, these men, in white and black jackets, are entrapped in a position in which neither side has a move–just like stalemate in chess. Their backs are turned to us as they deny our surveilling gaze, but their ghostly presence renders a phantasmagoria exposing the everyday reality for many Iranians facing the erosion of trust, hyperinflation, and social instability. To the Iranian audience, the claustrophobic setting of Ghahremani’s work may look uncannily familiar. Derailing the demand for democracy through years of reactionary politics, oppression, corruption, and incompetence, the Iranian ruling class has thrown the country into a state of total impasse.

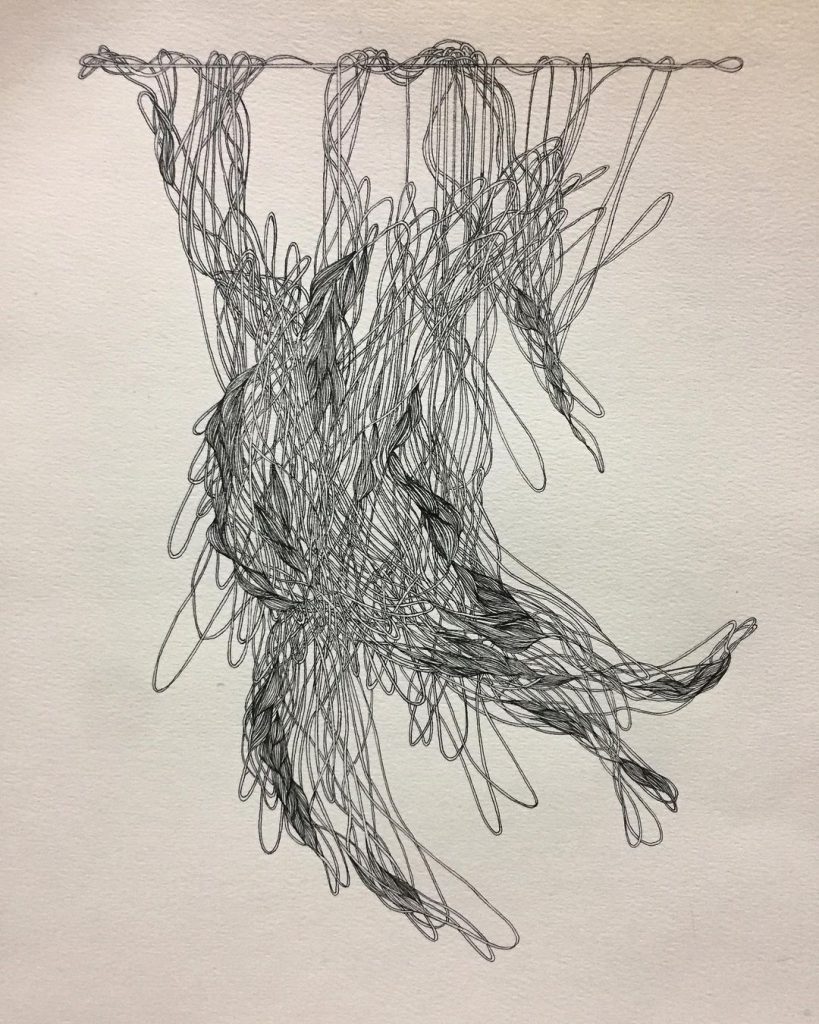

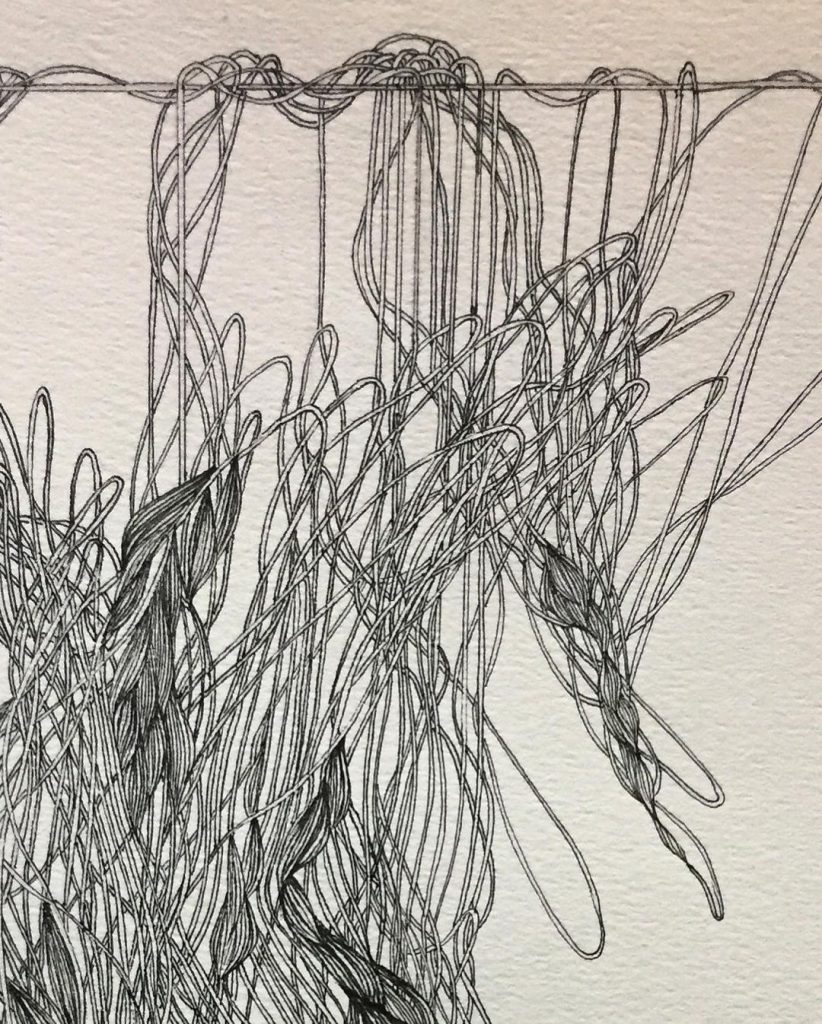

Unlike Ghahremani, Setareh Afzali lets space dissolve into infinity in her work, yet not into absolute void and weightlessness. In her piece Suspended (2019), gravity pulls down on a sagging cluster composed of braids and interwoven threads at the center of the picture plane (See Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the shape does not give in and holds on to herself. Rather than portraying an amorphous diffusion, Afzali portrays an anthropomorphic form in the process of shaping. For the past four decades, under the rule of the Islamic Republic, women have been a major force of resistance and emancipation, pushing against oppressive laws. In this sense, Suspended reclaims the agency that is in constant work to navigate and build in a socially and politically male-dominated space. Contemplating these works next to others in Space: Chapter One, I am reminded one more time to what extent space is political.

Visiting this exhibition prompted me to inquire into what Didaar Art Collective is and how it defines its place in the contemporary art scene of Iran. The following is my correspondence via email with the co-founders of Didaar Art Collective: Leili Adibfar, Azadeh Hussaini, and Yasaman Moussavi. I am especially thankful to Leili who worked on the final draft of answers to my questions.

Kaveh Rafie: Let’s begin with an overview of the Didaar Art Collective, its formation and its activities. What propelled your decision to found the collective?

Didaar Art Collective: The idea of Didaar Art Collective came out of friendly group discussions around visual arts and individual art practices of Iranian artists practicing in Chicago. It then gradually turned into a platform with specific pursuits of communication, interaction, and exchange of ideas in art practice and theory with a focus on both the Iranian art scene and Iranian artists in diaspora.

Didaar has been shaped and formed by Iranian artists and art scholars who share enthusiasm for and interest in art practice, history, and theory, and it is currently run by Leili Adibfar, Azadeh Hussaini, and Yasaman Moussavi. From the beginning, then, it has been important for Didaar to create a more cohesive relationship and cooperation between artists and art scholars, between art practice and theory. To foster an art platform that connects Iranian artists and art scholars in and outside of the country, Didaar aims to build a vibrant art community in which participants are able to freely and critically share their ideas and thoughts on different dominant art issues and approaches in the contemporary art world based on their professional and cultural backgrounds.

KR: The name of the collective, Didaar, is particularly interesting. Derived from didan (which means to see in Persian), it means (a face to face) meeting. In a sense, this suggests a bond between the artist communities inside Iran and Iranian art in the diaspora. What kind of reciprocity does the collective seek to establish between the two communities on a visual register?

DAC: That is an interesting observation, and yes, “bond” and “reciprocity” are relatable terms to define Didaar and what it seeks to pursue. In Didaar, this bond is imagined and made by an attempt to put both sides in conversation with each other as they each share common and different local and global experiences and concerns. In this sense, Didaar aims to help Iranian artists in and outside of Iran to know about each others’ practices, worldviews, and approaches and also to exchange ideas and experiences when needed. For Didaar, this task of course is not envisioned as a casual occasion to regularly meet, know, discuss, and debate, but is seen as a possibility to seriously cooperate and practice critical dialogue and thinking and making beyond the borders of the countries.

KR: Let’s talk about the range of your activities then. To my knowledge, you hold artist talks and round table series with Iranian artists and artists in the diaspora. The most recent one, for example, introduced the New Media communities and artists active in Iran.

DAC: In Didaar, we started our activities with studio visits, followed by group conversations about the works visited, and monthly discussions on designated topics in theory vis-à-vis art practice (e.g. Art and Market Discussion Series). According to these initial experiences and experiments, we then gradually directed our activities toward projects that address current practices, approaches, debates, questions, and concerns in the contexts we are focused on and working with. Through a process of thinking and planning, we now organize and curate a range of activities. To plan each project (e.g. Environmental Art, New Media in Contemporary Art, etc.), we design a specific approach to our ideas that can be executed in one or a couple of possible forms, such as monthly discussions of specific readings around the chosen topic, round tables, interviews, artwork reviews, on-site collective art practice, and curated projects like exhibitions. All these different forms of activities are united around the specific topic we choose for a project, and all our projects are planned and executed in collaboration with guest speakers, including artists, educators, researchers, and guest curators.

KR: Your recent exhibition Space: Chapter One at Oliva Gallery in Chicago amassed a considerable number of artworks from emerging Iranian artists. Why focus on the concept of space? How did this exhibition come about?

DAC: Yes, Space: Chapter One exhibits the drawing and printmaking practices of a group of emerging Iranian artists who, with the exception of a few, live across Iran. The idea of space came out of conversations among the three of us when we were holding on-site group drawing sessions two summers ago. During our sessions, we would discuss the personal and social implications of space at the present moment and the possibilities and challenges of its depiction in current practices of visual arts. At the time, we also were thinking about a common engagement in the works of many artists either living inside Iran or in diaspora, including ourselves, that seeks to investigate the ways through which we belong to [a] space or it belongs to us. The thing is, space as a containing framework is a ubiquitous concept. Yet, the variety of ways through which a relation could be made with exterior or interior spaces in their multiple dimensions and extensions make space a volatile notion in each instance of experience and experiment. This observation initiated the formation of Space: Chapter One, which is the first episode of an ongoing inquiry into the theme of space in visual arts. As the statement of the exhibition explains, “From interior landscapes to exterior environments, from the engagement with the dematerialized virtual space to the struggles for finding an actual place to live in exile or at home, space [in the works of this exhibition] is visualized in various ways through which artists contemplate and form their interior self in relation to the influences and effects of the external space. This could be an engagement with the sense of belonging or not belonging to a space, yearning for a (utopian) space, and/or striving to realize ambiguous relations with a space.”

To make this exploration open to artists in Iran and diaspora, we chose not to approach it in the form of a curatorial work and instead decided to announce an open call to ask for participation. We then made a committee of jurors that included the three of us and guest jurors with related but different backgrounds in art practice, theory, and history. The selection of the works by the jury members allowed for a collective process of choosing a range of artworks that visualize the perception or an idea of space in its personal and social connotations in addition to its usual physical and phenomenological attributes.

Our interest in the theme of space was also inseparable from the question of medium. The show brings together selected drawings and non-photographic print media such as etching, lithography, drypoint, and monotype. As the statement of the exhibition indicates, “Beyond the theme of space […] the show focuses on the specific media of drawing and printmaking as long-established media of the past in order to examine and showcase their two-dimensional capacities and other potentialities such as choices of framing the picture plane and plays with its material body in visualizing the multi-layered space(s) of today, whether perceived as entities, relations, or intuitions. The focus on the medium in this show also follows another intention, which is to seek to go beyond the cultural discourses that would reduce the work of these Iranian artists to the content of their practices in relation to the ‘marginalized’ geography they are associated with. Rather than asking how space is perceived and visualized in the work of artists from or associated with a specific geography, a look into their engagement with specific media allows us to ask questions about the role these media could play in the emerging practices of art (in Iran) and to reflect on the aesthetic dimensions of the works of these artists as the citizens of the world.”

When the pandemic started, our planning for the exhibition was enormously disrupted. Based on the individual and collective experiences we had gained over the years from the political relations between the two countries, we knew that waiting and postponing the exhibition does not necessarily make things smoother nor lead to better results. Now, in addition to the difficulties caused by sanctions, we had to overcome other problems caused by restrictions due to the pandemic. Despite all the problems and limitations, this project was successfully fulfilled with the dedication and cooperation of the members and friends of Didaar.

KF: The title of the exhibition implies a continuation, or on another level refers to an entanglement between time and space by anticipating a future. Was the idea behind this exhibition a one-time happening or do you imagine any future plans in relation to the idea of space?

DAC: Space is a broad concept and can be dealt with in multiple ways and through different lenses. Therefore, it has been important for us to not leave it as a vague topic and to explore it through as many specific approaches and viewpoints as possible instead. That is why we have been thinking about the concept of space as an ongoing investigation, and we currently are working on and planning different “chapters” as distinct frameworks to approach this theme in our future exhibitions.

Space: Chapter One was on view at Oliva Gallery from April 9 through May 8, 2021. You can view the exhibition catalogue here.

Kaveh Rafie is a PhD candidate specializing in modern and contemporary art at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His dissertation charts the course of modern art in the late Pahlavi Iran (1941-1979) and explores the extent to which the 1953 coup marks the recuperation of modern art as a viable blueprint for cultural globalization in Iran.