Starting in mid-March of 2020, the workplace, especially the corporate workplace, underwent a dramatic transformation.

For some, their workplace disappeared entirely as businesses had to go into lockdown as COVID-19 surged in communities across the world. For essential personnel, work hours and days expanded with the immediate and emergent demand for their services. For others, their work traveled from an office to their home, and they experienced the blending of work and leisure time that turned “working from home” to “living at work.”

A 2014 book by Jonathan Cray called “24/7 Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep,” which explores how the modern work environment intersects with digital technology to blur the clear distinctions between work life and home life.

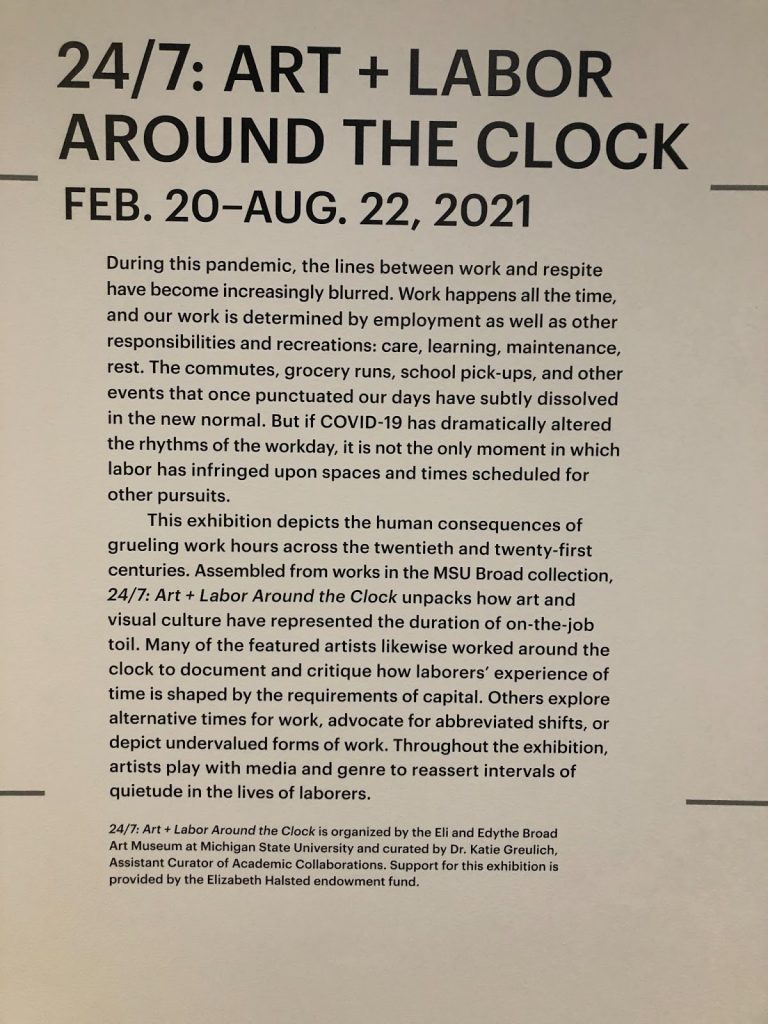

The ideas set forth in this book, drawn into sharp focus by the rapidly changing structure of workplaces during the COVID-19 pandemic, inspired curator Dr. Katie Gruelich of the Michigan State University Broad Museum to create the exhibition “24/7: Art + Labor Around the Clock,” on display at the museum until August 22, 2021.

Gruelich mined the collections of the MSU Broad and pulled together an exhibition of photos, paintings, drawings and video that explores labor in diverse industries and the way it takes over a person’s day, often eliminating any hope of participating in individual, family or community activities.

The basement room of the exhibition is small and out of the way — tucked out of view in the very way that society often hides uncomfortable issues of labor, such as masking the continuous expansion of labor by conflating a desire to carve out space for leisure and non-work activities with “laziness.” The room was originally designed to be a meeting room or board room, something Gruelich said contributed to the irony of the exhibition.

“We were talking about work life in a space specifically designed to be about the workings of a museum,” Gruelich said. “There are a lot of outlets on the wall and storage facilities that aren’t in other galleries.”

The walls are framed with two parallel lines marking three horizontal divisions of the room, with one line labeled 9AM and the other 5PM. The artworks themselves itself, images of laborers in their workplaces, breaks those lines, never constrained by the myth of those hours being the workday limits.

The works span more than a century with three pieces from 1910 to one from May 2020. There are many works focusing on the American Midwest and Michigan in particular, with others coming from as far away as Hungary. The laborers are a variety of ages, genders and races.

The exhibition explores labor time in two main ways, the first being the hours that the laborers depicted in the artwork put into their jobs, the second being the time that artists put in to create the pieces. The Hungarian series by Imre Benko, for example, was shot over a period of ten years and depicts workers in cots who are clearly living in their workplace.

“A lot of the artworks are very laborious to create,” Gruelich said. “Some of them are depicting work that happens around the clock and are also crafted throughout the day.”

Another example of this is a collection of four photos from the 1990s taken by British photographer Michael Kenna. Three of the sepia-toned silver prints are taken at the Ford River Rouge plant in Dearborn, Michigan. The plant was then in operation 24 hours a day, with three shifts keeping the activity in the building high all around the clock. Kenna’s images of the buildings take on an ethereal pall as he photographed them with extremely long exposure times—from early dawn to dusk. They challenge the idea that a photograph captures a single instant in time even while it draws the viewer’s attention to the expanded and constant pace of work happening within the building being photographed.

Gruelich dug deep into the MSU Broad’s collection to find works that focused on industries important to the Midwest region. These included such industries as automotive, steel and shipping.

One piece, a watercolor by Edith Butler, is almost deceptive in its peaceful depiction of the shores of Lake Michigan. It would seem to be a piece inspired by leisure and rest, a blissful day out in the embrace of nature. But the title of the piece indicates something the painting is trying to tell us—that work is never far away. Titled “Great Lakes Ore Boat: One,” the 1951 piece tucks in a shipping vessel on the horizon, nearly obscured by water and sky.

While most pieces are pulled from the collection, there are two open-source pieces that they are displaying for the first time.

The first is exhibited in a glass case abutting the entrance to the exhibition room. Gruelich calls it her “little dream space” as all the works suggest a relationship between work, sleep and leisure. There is a piece in it called “Goodnight, Zoom” that originally ran in the New Yorker on May 27, 2020. The digital print was created by Krithika Varagur and Eric Macomber and it is a reimagining of Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd’s children’s story, “Goodnight Moon.”

Ten panels immediately evoke the classic children’s book, using the same colors and drawing style. Each panel has the rabbit saying goodnight to things that rhyme—from screens to beans, and rants (with a toupeed and suited rabbit on television that looks suspiciously like a former president) and pants. The final panel shows the window of a bedroom at night with a moon that has taken on the appearance of the COVID-19 virus and is labeled, “Goodnight stars, goodnight air. Goodnight viruses everywhere.”

“That comic is so lulling and peaceful,” Gruelich said. “I read that story to my daughter every day. It has such a tempo and a rhythm for your day when you are at home. I liked that it recalled that little punctuation moment from childhood.”

The other open-source work was one of the most powerful and directly political of the pieces in the exhibition. It is an animation that loops on a television screen at the back of the room, intersecting the circle of artwork. The 6:25 minute digital video is titled “El Empleo (The Employee),” and is a 2008 creation by Argentinean artists Santiago Grasso and Patricio Plaza.

Available on Vimeo, it is a somewhat surreal narrative in which a worker wakes and moves through a world where humans are relegated to the status of common objects and are used without regard to any sort of self-worth or self-actualization. Everyone in it is gloomy, though for the viewer there are moments of guilty humor, escaped laughter at how ludicrous the objectification of humans are, whether it is the trenchcoat-wearing people in red, yellow and green shirts acting as a traffic light or the rickshaw-style taxi cabs the protagonist rides piggy back style. Without the use of language, the artists argue against the degradation of the human spirit that takes place in soulless work environments. Only at the very end, after the credits run, is there a slight hint at rebellion with the human lamp ditching the lamp shade in frustrated anger.

In the room next to “24/7” is a separate but related exhibit, a large media one featuring a transatlantic film that was produced on a shipping vessel. The floor also contains images of a car designer who worked for the Big Three automotive companies, General Motors, Ford and Chrysler. While they are not part of the “24/7” exhibition, they engage patrons with the idea of work, inviting them to talk about different forms of labor and industries.

“I wanted to bring something different to those conversations,” Gruelich said, then explaining what sort of breadth she sought in “24/7.” “I wanted to make sure I was pulling works that showed the diversity of work life in America in the 20th and 21st centuries. There is a wide range of demographics including child labor, people working at older ages, and a diversity of race, ethnicity and gender.”

While the exhibition is a small one, Gruelich manages to give patrons a lot to think about in a world where work continues to evolve and not always for the better.

Featured image: An installation view of the exhibition “24/7: Art + Labor Around the Clock” at the Michigan State University Broad Museum. Seven images and a block of text describing the exhibition can be seen hung on a white wall. Two parallel lines run horizontally across the wall: the top line is marked “9AM” and the bottom is marked “5PM.” Image courtesy of MSU Broad Museum.

Bridgette M. Redman is a Michigan-based journalist who writes about the arts for publications in Lansing, Detroit, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, Santa Monica and Houston. A member of the National Theatre Critics Association, her theater writing appears in several national publications. She is a second-generation journalist who believes in the power of art and writing to change our communities for the better.