A Midwestern spring at its best brings the slow thaw of snowbanks, the reintroduction of mornings full of bird chatter, and the quiet transition of blank branches to full blooms igniting a symphony of smells. Having lived in the Midwest my whole life, I have become familiar with the cyclical nature of the changing seasons. I have expectations for how the spring will look, feel, smell. Yet each spring comes with a surprise. As we succumb to the effects of global warming, I consider the realities of spring at its worst: snow melting rapidly enough to cause house gutters to crash to the ground; flora and fauna believing these 36-hour summers to be true, making their reappearance too soon to sustain.

I visited Suzanna Zak’s exhibition Flesh of Earth at Prairie gallery during the same week as Earth Day, and I have found a substantial and interesting relationship between these two events. Earth Day serves as a moment for us to reflect on our relationship with the planet, appreciate its beauty, and consider how we can do our part to promote sustainable practices–like minimizing our own generated waste, supporting local, changing our diets to be more environmentally friendly–rather than destructive practices such as choosing to ignore the amount of plastic bags we use or buying from big corporations with bad environmental practices out of convenience. Our relationship to the environment is complex beyond reducing, reusing, and recycling. Conversations of predators versus prey are where these complexities come to light. Certain invasive species and predatory animals don’t always receive the same protection and care from us as their victims do. Rather than spending all of our energy protecting and running from predators, what happens when we, metaphorically of course, run towards them? Flesh of Earth creates a world in which the predators and the prey coexist, and sparks a conversation surrounding ecology through sculpture, photography, and text. Zak’s interesting use of imagery, dedication to her concept, and prevalent experience on the subject come together to form a truly exceptional exhibition.

The exhibition text by Tamara Becerra Valdez provides successful insight into the complexity of our relationship to earth in a way I have not encountered before. Powerful, poetic, and realistic, Valdez captures a unique perspective on land and human’s impact on it. This is perfectly articulated in the line, “I do not know the best way to use this land, nor do I believe that anyone else does. I no longer expect to live to see it, or come to its best use.” It sets a precedent to the viewer that no right answers on how to change the trajectory of our Earth’s fate will be easily given to them. Not because Zak doesn’t want to show her cards, but because no one holds the cards to begin with.

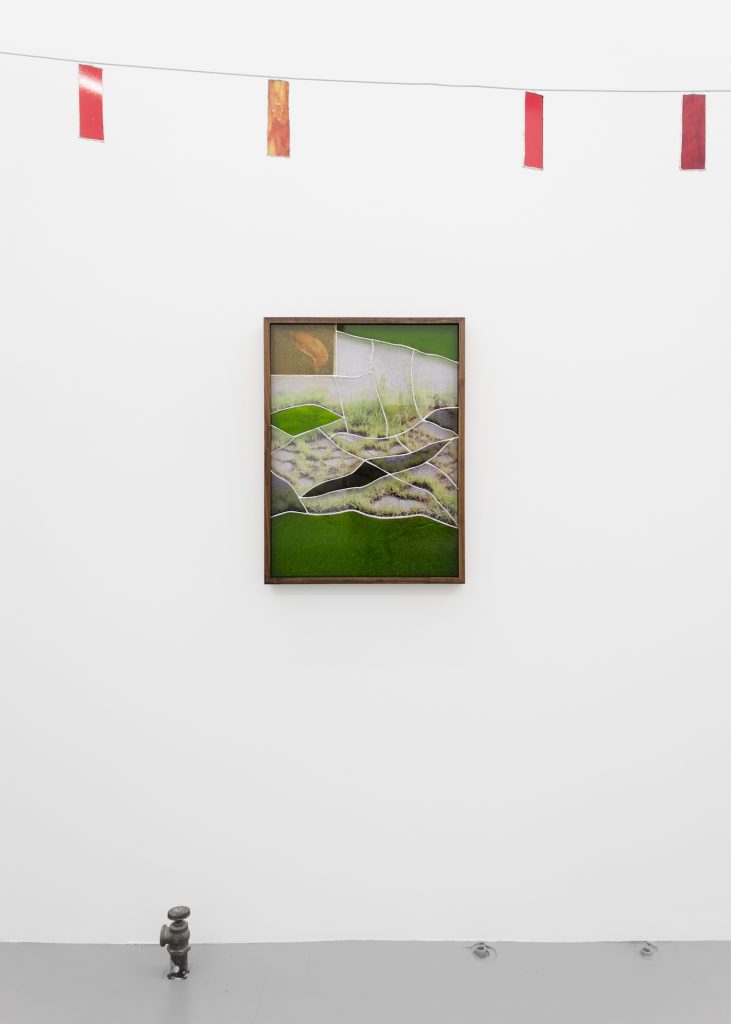

In Flesh of Earth, there are two predominantly green pieces that capture my attention: The snail (Helix pomatia) is probably the most common of the gastropods, though in fact is the most specialized and one of the most recently developed, being a terrestrial animal and breathing by a kind of lung. The majority of gastropods are marine animals and breathe by gills, as well as The slugs belong to the purely terrestrial order Stylommatophora, an order that has shown wide adaptive radiation and has exploited a large number of habitats on land. The mollusc shell is here reduced to a few calcareous hanules as in Arion empiricorum. Both pieces are made from C-prints, found print, lead-free solder, and glass. The printed images appear to be roughly two inches behind the glass, creating a distinct foreground and background. The gap between the prints and glass causes a strange illusion of movement depending on the vantage point you are viewing from. If looking straight at them, the gap appears non-existent, as if the glass is placed on top of the prints. As I inch closer, I find the images and glass separate more and more. With these pieces, the height and distance of the viewer play colossal roles in the resulting perceived image. This effectively creates a pulsing sense of movement that reverberates throughout the rest of the exhibition. Though made from static images, the movement Zak captures is reminiscent of wind running through grass, shifting tiny blades just enough to notice, but only if you are paying attention.

There is a visually dominating piece, Long Weekend Interfacing (Working Title), made from a sleeping bag, digital prints on fabric, and a t-shirt. The prints depict various striking natural scenes including lush, grassy grounds and wolves trotting across a frozen pond. The photos were taken by Zak over the past several years. Zak’s ability to capture photographs of these wolves introduces the relationship between the artist and predators that continues throughout the rest of the exhibition.

Perhaps the most powerful element in this piece is the use of the sleeping bag. Sleeping bags by design are tender vessels that allow humans to experience an intimate, restful moment with the earth. In this piece, the sleeping bag serves as an olive branch, extending from the artist to these predators.

Long Weekend Interfacing (Working Title) also contains a t-shirt that has the portrait of a wolf printed on it, with a phrase reading “predators keep the balance.” This text reiterates Zak’s perspective on our relationship to predators even further. When I see the t-shirt, I am immediately reminded of the cheap, decades old, thrifted t-shirts with wolves printed on them that a beloved friend of mine would give me to sleep in. Zak informed me that the t-shirt was a treasured gift from a friend. The t-shirt brings a level of sentimentality to the viewer that again reinforces a warm and inviting approach to predators.

Gently tucked away in a corner of the gallery is a piece, Bones Raw to the Air, the Source and Shape of the Sound, created by a steel stand and coyote skull. Instantly, a sense of mystery enters the conversation. Where was something of this nature acquired? Had I not seen the rest of the show, I would have assumed it was sourced online, or through a friend of a friend. But, sitting next to Long Weekend Interfacing (Working Title), reminding me that Zak captured those striking images of wolves herself, and she could very well have sourced this skull in a similar natural, self-sufficient way. The size and stature of this sculpture feels purposely underwhelming, and works to show the viewer the fragility of all life, predator or not. In no way does this piece serve as a trophy or victory over the coyote, but rather a sympathetic homage to the life the coyote lived.

Fladry Line (Thirst for Life), is a sculpture that shapes a perimeter of a square in the center of the gallery, made from glass, lead-free solder, poles, and wire. The glass is a range of burning oranges and reds, igniting an illusion of fire. Against the complementary greens in the previously mentioned pieces and the stark white of the gallery walls, the sculpture takes on a commanding presence. Though utterly beautiful as it captures peppering flecks of light, there is an additional sense of alarm. I admire this work the same way I would admire a wildfire: equal parts marvel and panic.

The sculpture, obvious in its title, exemplifies fladry lines which are used to keep predators out of designated areas, usually wolves and coyotes specifically. The most powerful element of this piece is its positioning: the square shape creates the “safe zone” (i.e. inside the fladry line) to coincide with where the viewer typically would stand to view the rest of the work. All of the other pieces reside in the unprotected area outside of the fladry line. The predators depicted in Long Weekend Interfacing (Working Title) and Bones Raw to the Air, the Source and Shape of the Sound, are kept outside of the protection of the fladry line. Zak could have made the choice to protect the entire gallery space, positioning the line to run the perimeter of the gallery instead. However, she offers the viewers the choice to step outside of the “safe zone” and get a closer look at these alluring animals. This reinforces the importance and fascination these predators provide to Zak, and as a viewer, we know exactly where she stands when given this choice. As if the collected coyote skull and the impressive closeups of wolves don’t already prove this, Fladry Line (Thirst for Life) solidifies this.

The most compelling aspect of this exhibition is the positioning of the pieces. I imagine the installation process was reminiscent of setting up camp: the sleeping bag offering a place of rest, the fladry line adding a cloak of protection, an old T-shirt to sleep in, the lush printed images serving scenic surroundings. All of these are elements of the perfect campsite. However, this perfect campsite is challenged by the positioning of each element. The “safe” area inside of the fladry line is only ever occupied by the viewer. Zak positioned the piece Fladry Line (Thirst for Life) with tremendous thoughtfulness. The viewer was forced to step into the “unprotected” portion of the gallery in order to fully view, experience, and grasp each of the other pieces in the show. Leaving the known, safe, protected area, and venturing into the “unprotected” is entirely necessary and worthwhile, and Flesh of Earth is no exception.

Flesh of Earth is on view at Prairie through May 22nd. More information about the exhibition and open hours can be found on the gallery website or @prairie.chicago

Featured image: Installation view of Suzannah Zak’s exhibition Flesh of Earth, at Prairie. The left wall includes two predominantly green pieces with prints behind lead-free soldered glass. Towards the center is a photograph of footprints in the snow, titled Many Animals Including Human Beings Traverse Through Snow. On the right side is Long Weekend Interfacing (Working Title), a red sleeping bag with digital photos and a wolf print t-shirt attached to it. Towards the ceiling, running a square around the room, is the piece Fladry Line (Thirst For Life), containing various shades of red glass, lead-free solder, poles, and wire. Photo courtesy of Prairie.

Ally Fouts is an artist, designer, and writer living in Chicago. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Art, Media, and Design from DePaul University. More information surrounding her artistic practice can be found on her website.