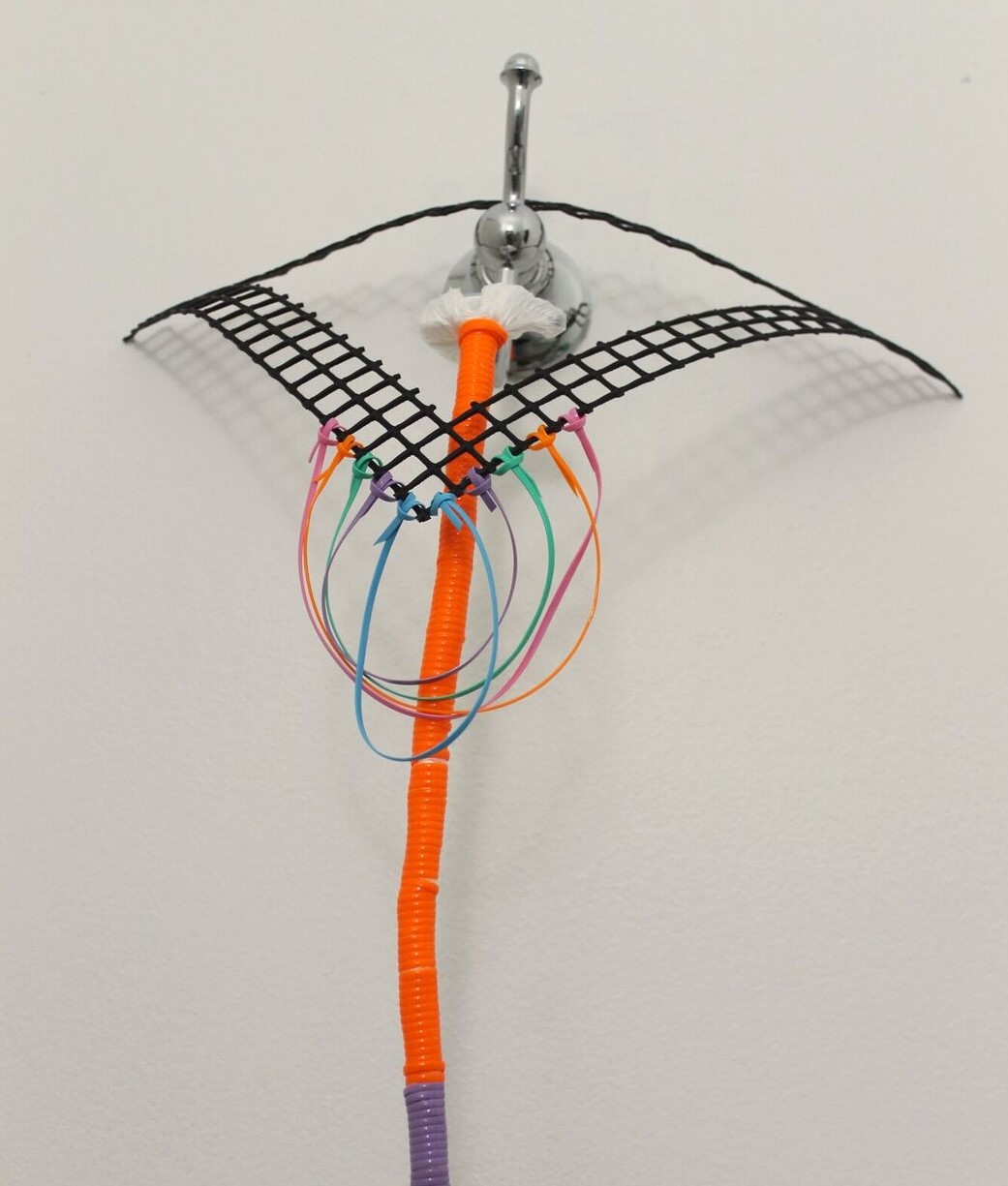

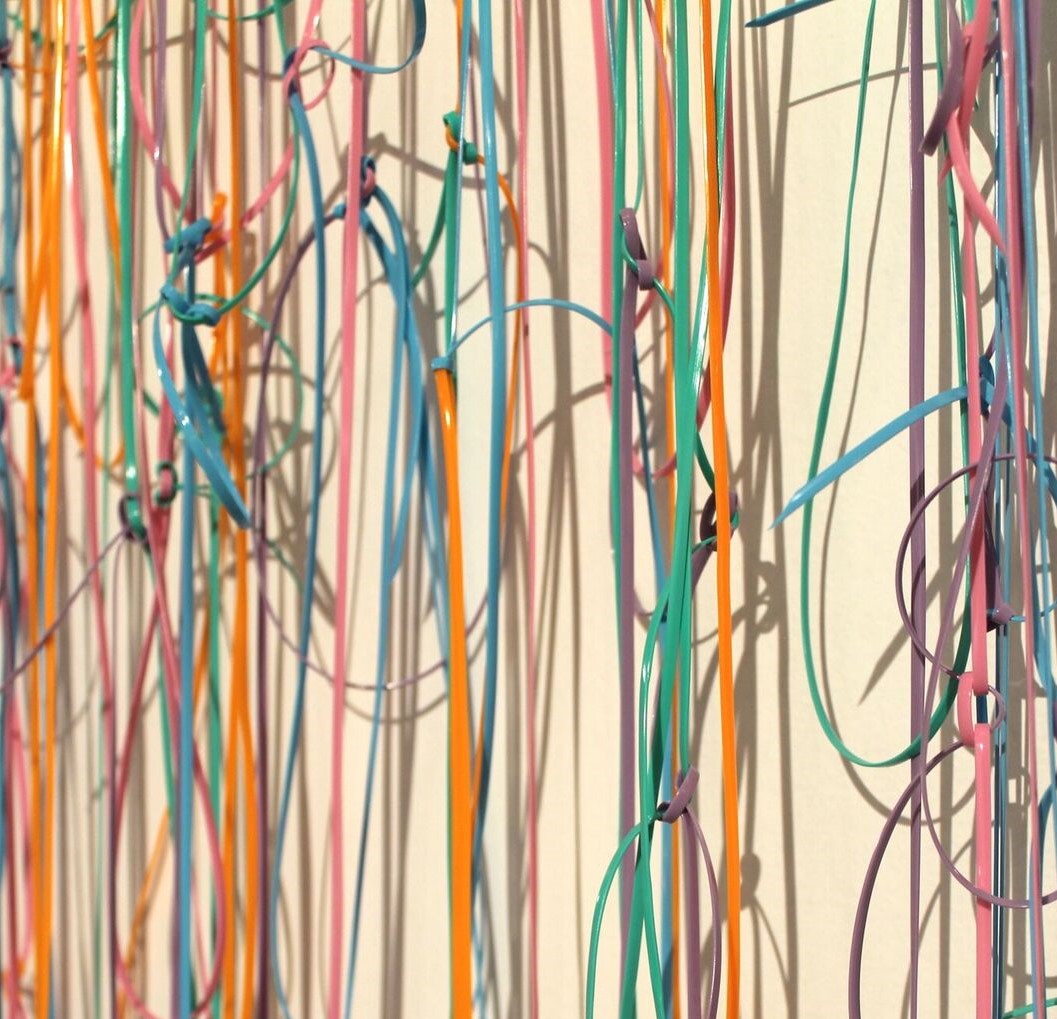

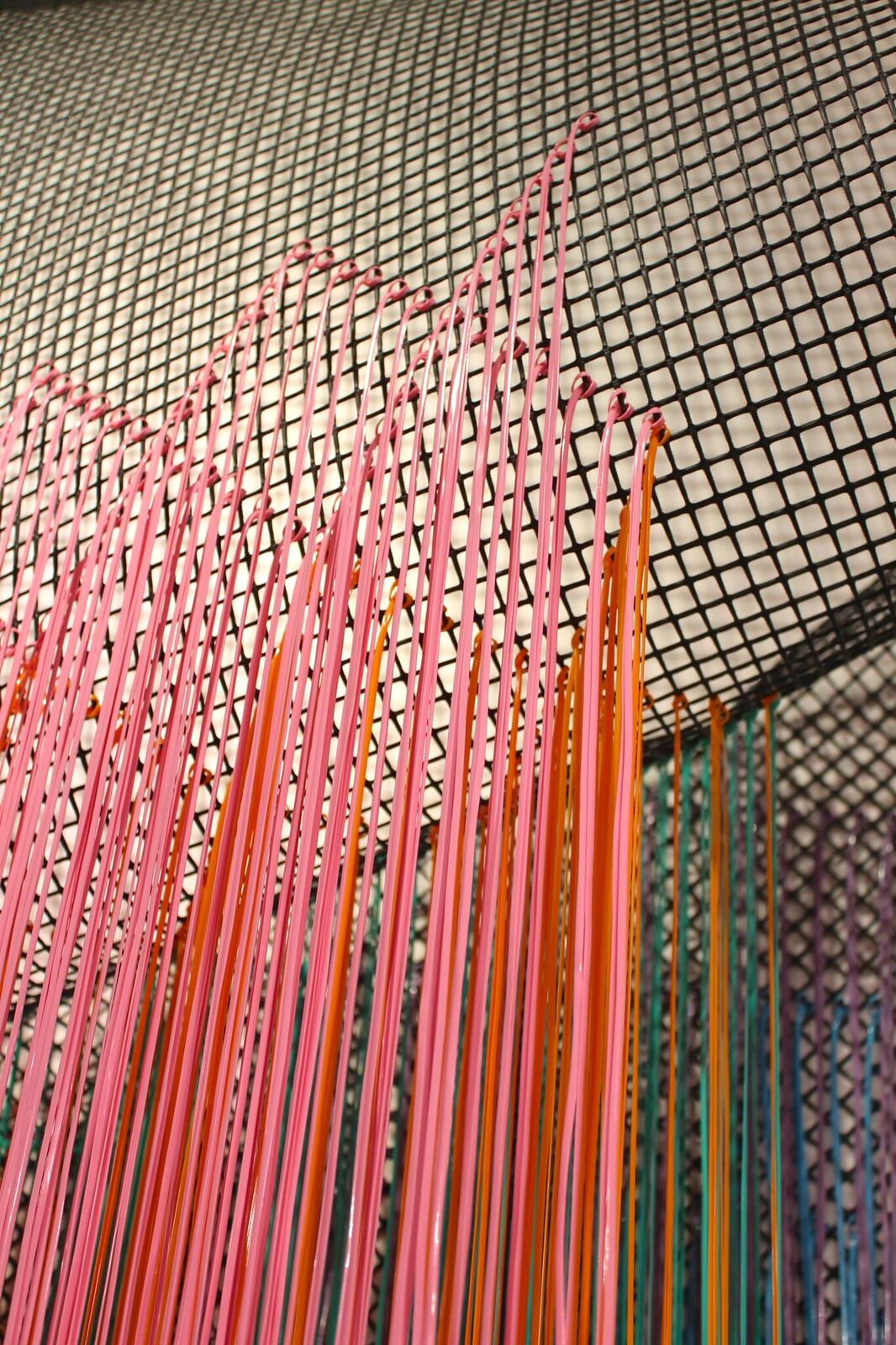

José Santiago Pérez’s show, Flirting with Infinitudes, part of the Doing/Thinking residency at Wedge Projects, will be on view until the closing reception on October 5th. The pieces in his show activate the triangular gallery space with their touches of bright neon colors. In Flirting with Infinitudes, Santiago Pérez uses knots as a way to meditate on time and its the cycles and repetitions, and ultimately on what binds us. Some of the pieces evoke tapestries made with modern materials, the colorful plastic cascading from the knots that affixing the lacing in place against a dark grid. Other pieces contrast colorful materials against the translucent, one material contracting and ballooning against the coiling and releasing of the other. In still others, the translucent white plastic hangs in strips that partially veil the vivid looping and knotting. The show is accompanied by a takeaway booklet that continues the show’s meditations in text form. I got a chance to talk to Santiago Pérez and we discussed the show’s craft-based process, the use of knots, and the transition from performance based work to exploring materials as an aspect of time. Throughout our conversation we easily vibed into and out of Spanglish, connecting over being able to express and explore aesthetics from a shared fluency and understanding the value of the bien hecho.

Santiago Pérez will also be part of a group show at NAPOLEON in Philadelphia and will have a show at Ignition Projects in Humboldt Park in 2019.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes: How would you describe your work as an artist?

José Santiago Pérez: I think it’s a little unruly and it’s meandering. I’m process driven and so things like wandering and meandering are important to me. I always start work through walking … That associative meandering, I would say, is at the core and something that is movement and body based. So that doesn’t always appear in the work. But that’s the background that I always start with. Whether that ends up being materialized as a performance, a durational performance or performance based sculpture or, in this case, object based work, the body is always central. And my training as a performer and further back in theater, that vocabulary as a mover, as an embodied phenomenological sentient being is sort of where everything starts. And then it’s just a matter of finding forms or discovering processes that are either directly or in proximity to things that I’m thinking or sensing or feeling.

JPC: Can you tell me about the show? What was the inspiration for it or what what are you interested in exploring?

JSP: So the show. It’s kind of a transition. I’m in a transitional moment right now. I just turned 40 and I’m in this transitional moment where I have to come to terms with the fact that my body no longer wants to do the things that I was demanding of it. I was doing long durational, heavily physical work. It was causing me a lot of physical harm afterwards that wasn’t something that I was interested in, in the work itself. It wasn’t this endurance thing, the ordeal. That wasn’t interesting to me. It was more about the body encountering a material. And having that dance between body and object being the thing that generates something. All the aftermath of that, the wear and tear on my body just became a huge factor. So I had to think about, well, what happens when the fleshiness and the wear and tear on my body no longer allows me to do the things I wanted to do. Where can that energy go? And so I had to think about, well, if the folds in my back, and the back of my thighs can no longer do that work. If I consolidated that energy maybe into my fingertips, into my wrists, into my elbows what happens when that dance is sort of taken away from the entire body and just isolated in the fingers. That’s the background. I’m in transition, trying to figure out what to do. Trying to conserve energy and do some self care, basically.

And then also thinking about the wear and tear, psychically, of exposing a nude brown body to a primarily white evaluatory art gaze and what that means for me, now, at this point. And then I’ve always been interested in fiber and materials and I wanted to maintain this relationship with plastic that I’ve been working on for about four years. It was just pivoting slightly, turning a corner and thinking about “OK, what about focusing on fingertips?”

JPC: I like that you’re describing it as a dance because you can really see with the knots that you’re using, how the hand would form the knot.

JSP: Thank you for picking up on that. I think that’s another element of the work. Where previously, not because it was, but it was received as a mystery of how this happens. How does this dance happen because it’s not choreographed, it’s improvised. And I was less satisfied with that mystery element because there’s nothing mysterious about it. The body just does whatever. You have to wrestle with what you’re met with. Here in this case with knotting, with coiling, there is a way in which, if you attend to it, you start to see those moments. You start to where a knot was a little too tight. Or you start to see the rhythm of the hand, kind of like annotation, or documentation of a finger dance. To use that sort of inappropriate concept onto this thing.

And it’s really gratifying because the scale is small. This way of making is lining up with my temperament as an introvert where I’m giving myself permission to do that without the imperatives of extroversion and spectacle. I’m asking for a different viewing experience and I’m demystifying process — it’s not hidden. Yeah, it’s not hidden in any of the work. It’s not a mystery being beamed down. … I think craft practices are handed down. Whether you’re apprenticing or whether it’s family traditions. There’s no real ownership. There’s no patent. To coil is something that a 3-year-old can do, a 98-year-old can do, a 40-year-old. They can do it together, they can do it separately. Ad what you’ll get is probably just gradations in rhythm and pace. It’s just kind of lovely.

JPC: There’s something challenging to the idea of the artist in the White Cube space of, like “no one else can do what I’m doing.” Maybe democratizing it. Would you agree?

JSP: Yeah, and I think at first I hadn’t thought about it in those terms. But I think there is something about that. I think I was struggling with and trying to find ways that … I think about my family coming to shows and seeing things. I want my grandma to get something out of it. I want her to come without any background but with her own aesthetics, her own sensibility. And how would my neighbor’s 3-year-old kid, would she have an experience too? And that can be problematic too in the sense that you can’t do all things for all people. But I want to find access points for everybody.

That it doesn’t require a bibliography necessarily. We can talk about about the bibliography, but it’s not required. And I love the ways in which now my practice opens up to conversations with my family. My mom can obsess about how bien hecho something is. Like “Oh, I see that you did this.” And that’s something that for me is super nourishing, especially when I was sharing embroideries with my mom and with the rest of my family. Which just happened in the last couple of years. Whereas prior, any of my creative endeavors sort of locked them out. Not by intention, just because, you know, there was experimental theater this, and performance art that. There was a distance that they had to try to travel.

JPC: Like “¿Qué es eso?”

JSP: Like “¿Qué es eso? ¿qué estás haciendo? Te estas revolcando ahí desnudo.” Like “what are you doing, right?” (laughs)

JPC: (Laughing) Right, right. And it’s something shocking for your family.

JSP: Right, and it’s not that I’m changing for them but it’s more about…I think it has to do with being a little homesick. I haven’t been back to L.A. for a while and so I am wanting to just bridge that gap a little bit. And feel a closeness and re-engage that attachment. It’s more important than I think I wanted to admit. For whatever reason, the academy shames us into thinking a little bit in those terms.

JPC: And there’s there’s lots of issues of access and things like that. One of the first things that I noticed when I came in here was the baskets and that did come into mind for me, like mira que bien hecho.

JSP: Bien hecho, right. (laughs).

JPC: All the little knots are so tight and the baskets themselves reminded me a lot of basketry in my own community. Where is your family from, by the way? .

JSP: We’re Salvadoreños.

JPC: I feel like there is a visual language that maybe people outside of our communities might not necessarily think of right away. The artesanía that we were talking about, the handiwork.

JSP: Handiwork. And it’s interesting because in different publics or for different communities, there’s value in different aspects of that. On the one hand it’s that thing that we notice, “ah, que bien hecho.” And where there’s value to that, in many instances, in many of our families and communities we have those traditions. The well-made, functional object is something that is prized. Value comes from the object that’s integrated into your everyday life. Perhaps in some instances, versus maybe in like the art world, it’s something that’s removed from the everyday life. And I’m not saying that one is more or less. But I think that basketry and the processes of basketry allow for it to speak in multiple languages.

JPC: We were talking earlier about how something like basketry would usually be done with natural material and the lack of access to it here and how you use plastic and how abundant it is. Can you talk about the materials you use?

JSP: Yeah. So I think one of the things I was drawing on was from my positionality. Born and raised in Los Angeles. Child of Salvadoran immigrants and then you have to think, the ’70s, ’80s, not having the ability to just go back and forth between countries because there’s a giant civil war that’s happening. So there’s a way that I experienced life … For me, it was like I didn’t have access or I couldn’t reach for that thing that I really wanted which was, to participate in the embroideries of las tias.

So where does that energy go? It goes to the nearest thing. And so everything is plastic. It’s the cheapest, the most accessible material that one can play. So that’s one way, but then there’s a way in which the sense memory of playing with plastic, manipulating plastic, has been with me for a long time. And I recognize it as being a little bit off. Why not peluche? Why not something soft? But there’s something about the quality of plastic that is a little bit repulsive to me, but it’s also super attractive. So I was trying to figure out what that’s about. And I started thinking more deeply about plastic. It’s everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It’s visible and invisible at the same time, which I think I’ve lived that way too in the world, being invisible, being erased but being continuously present. But what does that mean in terms of some communities… It’s the office workers that come to clean our offices in the middle of the night. My mom was a domestic worker. So, you know, when they’re away, the maid comes to clean. That concentration of labor on unvalued bodies, that’s one other little knot that I’m interested in undoing and redoing too … So these are the things that we come to understand plastic as cheap, as readily available, as unvalued, as counterfeits, as fake. But entire industries, the geopolitical apparatus that makes the oil industry possible is wrapped up in all kinds of value, all kinds of money. Redrawing national boundaries. All kinds of geopolitical aspects that have been cleared away so that we can buy our Tupperware or buy our plasticos and can only charge seven cents for a bag at the store. You just no longer think about it. And that’s the other thing too.

It’s disposable but these these objects, the baskets in particular, aren’t going to show any kind of wear or minute cracking for at least 25 years. I mean they’re going to outlive me. They’re going outlive many of us. And that contradiction is something I don’t want to resolve, but it’s a contradiction or a problem that I want to take on and stick with and be nearby primarily in an art sense because it’s about time. Something that I mentioned to you earlier was thinking about plastic, and how not only will it outlive us, but it actually predates us. Or the raw material that goes into it — petroleum, fossil fuel, black gold, right? That’s the Neolithic period. We’re touching dead seas when we touch plastic. It’s an exhumation of what’s beneath our feet deep down. It’s under the ocean. And that’s time. That’s the accretion and accumulation of time. And it’s interesting how wasteful we are with time. We totally throw it away so fast. Se me hace super curioso. And it’s also problematic. Then again, I don’t have the answers, but I think that’s where my obsession with thermoplastics comes from. It’s like oh shit, they’re our ancestors. This is accessing antiquity.

And then thinking about the — more of the specific articulations of what is plastic. I use a lot of black mesh, the grid, and it just so happens that the grid and basketry developed in the Neolithic period almost simultaneously. My mind just wants to go back, not just in my lifetime, but think about time in really long stretches. And so, not only has the raw material for plastic always been with us, but the grid has always been with us. Basketry has always been with us too. And there’s a way that they persist. And I think that persistence, the insistence on being here that’s where my story, or the communities that I’m always nearby or in, that I feel like in this age there is a sense of needing to insist on persisting, on going on. Whether that’s through repetition of being or repetition of getting up everyday. So there’s something that dovetails with that, that is knotted into that.

JPC: Is there an element of moving from a time based performative practice to moving to using a material that represents time for you?

JSP: Yeah, absolutely! It’s funny, right, and it’s almost metaphorically plastic as a surrogate, right? So if there is a way that a surrogate for time for the experience of time, I think you’re spot on, there’s a way in which I needed to find a way to still touch time, to work with time.

And I think that’s how I ended up really excited about Wedge Projects and their Doing Thinking residency. Because. It’s really about time. It’s about showing up for a duration of time and having the freedom to just be in time with whatever it is that you’re doing. That’s the way that I feel that I really love making, to have that time and space, the luxury of time and space — the luxury of time and space — to be able to just be with a thing, you know? Be with a couple of things for a really long time and just see what happens.

JPC: Can you say a bit more about the knots? You were talking about the double hitch one.

JSP: So the double hitch, it again it’s like the plastic of knots. It’s probably one of the most ubiquitous, so there’s nothing very special about it but one of the things that I love about is that you find it in so many different instances of everyday life. It’s really common right now in macrame, it’s the way you lay down your lines on the bar. That’s the first initial knot, the foundation. It’s a beginning. I think in knitting too, when you cast on to a needle there’s a very similarish knot perhaps. So that’s one instance of macrame so it brings in the craft-based fiber art thing. It’s also used in sexual play too, in bondage. … And I think it’s just a very easy knot to do. I think we find it in a lot of places. It’s not quite the hooking of rugs, but it’s very similar. Also in tapestry, we use that as a rya knot and usually for the rya, I believe you use that to bring two warp threads together. So it’s a vertical thing. And I tend to use it on these grids on the horizontal so that’s a difference. It’s just the orientation. So it’s a really versatile, ubiquitous thing. I am just in love with it because it’s a fundamental. It’s a no-brainer. There’s nothing really special or super intricate. In sailing too it’s used. As part of that nautical tradition. And another thing about the nautical tradition too, depending on who you ask it’s either super problematic or this kind of wonderful thing, discovering the world etc. right? So it’s complicated but in terms of the knot itself, the knot migrated in an interesting way. Knots were exchanged almost like currency among sailors. So a way you could learn and increase your viability as a sailor would be to acquire as many knots as possible.

JPC: Earlier, I brought up just how knots figure into some of the spiritual traditions. For me, they remind me of amarres in brujeria and in those kinds of things and relationships and all of that and I didn’t want to impose that onto the meaning. But I do think it’s interesting, all the possible associations, just seeing so many knots play out in your work.

JSP: I love that that was available for you as an entry point. When I think about my great grandmothers, which is like a forbidden zone for me, she didn’t like anybody to touch, of course but I remember there were crosses and figures wrapped in red cloth, not knowing what that means but I think that there’s there’s something about knots — the knotting of something, the wrapping of something that’s about either reiterating a relationship or undoing and unwinding a relationship. It’s about contact, it’s about being, depending on the tightness or looseness of it. There’s so much in terms of relation that you can extrapolate from those things. For me attachment is really fundamental, thinking about it not just psychologically. Mostly psychologically, the energy of attachment gets materialized this way. You know? What is it that we attach ourselves to? What do we bind ourselves to? Who do we bind ourselves to? For how long? Who decides?

All that context of relation happens. And there’s something magical about physicalizing, materializing knots. To have intention, have emotional content, imbue that thing that you’re doing.It’s understanding I’m not super knowledgeable but there is something it makes sense to me about a line that turns on itself. A line that connects one thing to another can be such a powerful thing. A knot super-connected, there are geometries that are super connected with all kinds of spiritual practices. And I go back to the title of the show — it’s a way, it’s a human-scaled way to think the infinitude, think infinity, think or be in relationship to something that’s almost too big to even capture. To be inside a triangle, to be outside a triangle, to be triangulated. A triad. Padre, hijo, espirito santo, all these things we live in that are really potent. So there’s something about the mystical, being nearby the mystical, because I can’t make a claim to that, I think that would be really disrespectful to do that, but I think there’s a nearby-ness to that, that I think there’s some of that energy, like intention. Yeah, it’s nearby.

JPC: And so yeah I noticed that with the shape of the gallery too, right? [laughs] It’s very triangular shaped.

JSP: It ended up working out really well, because it’s an inhabitable triangle all the time. The way that that comes off the walls and I needed to be here. I need to be here in duration. And there’s something about honoring the space that you’re in — it sounds really silly, but it’s a way to thank the space for helping me think and do in these directions. So there is a way that the pipes are now starting to be integrated into, in really small ways.

JPC: I wouldn’t have noticed that at first, that’s so great!

JSP: There’s that impulse of a gallery to try to neutralize it as much as possible, to fit into that white box thing. This is kind of a white triangle but it has its perks so it has exposed pipes. It has this this window bars grate thing. That I think most of the shows that I’ve come to see here completely try to ignore it. And there’s something about the impulse to ignore a thing that is unvalued, that is you don’t want to see that but I wanted to actually bring it in.

JPC: Yeah, that really draws attention to it, sort of decorates it almost.

JSP: It kind of decorates it and there’s this sort of mariconiado faggotry about the impulse to still decorate the thing. And so for me decorating is not a bad word. It’s about this impulse to sort of change or transform something that’s in your space. But yeah, so the pipes are being integrated. I’m wrapping the pipes so there’s again a sense about wrapping and what that means for me personally as I do it. You know again, it’s time, but it’s also a mark of distance and shifting proximity, shifting distances. Something goes away from you, something comes back and I think that’s where something we’re talking about about the traditions of wrapping and …

JPC: Wrapping away and wrapping towards, yeah.

JSP: Wrapping away, wrapping towards, you know, a relation, an object, a person situation or whatever. It’s going away coming back and continuously cycling through that that I wanted to work in to the pipe. And it’s also the same like coiling, the tradition of the baskets. Except that instead of it being the soft plastic core inside the wrapping, it’s now just, it’s a pipe. So that rigidity. It’s not gonna bend, I’m not going to be able to coil a pipe. But I wanted that to be in there. And also just piping, like that’s a return pipe. So thinking about turning and returning and then also have a return pipe just repeats, it’s a repetition of that same idea.

JPC: How do you choose the colors for your pieces?

JSP: Well funny enough, part of it was random. And then part of it was random because for the plastic lacing it’s mostly really bright colors but then I started to form biographical associations with color. Color in relation to certain relationships … And I started to think about a certain basket in relation to a certain relationship and the basket then becomes a vessel — it’ll contain maybe a memory, a kind of emotional material from that relation. It’ll hold the secrets of that relationship. It’ll hold the memories of that relationship, the hurts of that relationship.

Finally there’s a there’s a way to hold it. Hold it close and set it aside. And I think that I’m kind of a melancholic in the sense that I sometimes want to hold that holding, I want to hold the holding. I want to hold and touch that relation or that memory of that relation. But again those are my own personal associations. But we all have different associations with different colors. That’s another way, an access point. The brightness of colors. I also think about the 99-cent store in LA, growing up going to the swapmeets. Plastic, Xuxa shoes, it’s an era where, you know, the ’80s in LA was neon and bright, and the quality of that light, and at sunset, just the pretty colors, it pops and it’s loud. And I used to distance myself from that, but I’m coming right back to it,

Like I mentioned earlier I’m a little homesick, so when I think about LA, not LA right now, but that home that I get sick for is the LA that I grew up in. There’s so much of that color. And I always grew up and las ninas de la vecindad. So there was always colorful ruffles, and the ruffled tops, in pink, and like revuelos and that kind of thing is a bit cursi but I love it, because it was in those little spaces of childhood and being surrounded by girls, I felt held. And I felt accepted as an effeminate little boy. And also because I was super jealous of all their clothes and Barbies and stuff. I didn’t get to have them, so now I can have them, now I get to have my rosadito. So that’s a little bit about color.

JPC: And so the last question I have is what do you hope that people will be able to take away from the show?

JSP: That’s a great question. Aside from the text piece that is available for the audience to take with them I think that maybe just — nothing grand — but maybe just an invitation to pause and take a look around. An invitation to look and see what’s hidden in things…to stop and see what is hidden in plain sight requires a slowing down, and a kind of attention to being where you are, and being near to approximate objects. I think if anything there’s an invitation to slow down and stop and just look around, and there’s a lot to be mesmerized by.

Featured image: Detail of untitled piece by José Santiago Pérez from Flirting with Infinitudes. Photo by Melissa Patiño Cervantes.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.