It is rare that a show’s theme so closely mirrors the circumstances of the gallery where it is being exhibited as well as The Strange Fields of This City, curated by Greg Ruffing and features the work of HATCH Projects Residents Alejandro Waskavich, Haerim Lee, and William Camargo, on view until June 14th. Along with Brent Fogt’s Do Something Else, it is the last show at Chicago Artists Coalition’s space at 217 N. Carpenter before they move to their new location 2130 W. Fulton. Facing the same pressures of space and development that the show tackles, along with expanding needs, CAC is finding itself having to relocate, like many other arts organizations in Chicago. Peering into the gallery’s windows to see William Camargo’s oversized, rasquache-style advertising signs of Cultura a la Renta critiquing displacement, it is difficult to ignore the construction noises of the high rise going up across the street. Gentrification is in part a war of aesthetics. A war of the undifferentiated, the sameness of developers using profit maximizing, corner-cutting tricks to convince people living piled on top of one another in identical shoe boxes that they are living in luxury because of what is now absent – the Other.

The aesthetics of the Other vary in their specificity, but are the aesthetics of our everyday. They are the empty Jarritos bottle and bag of tostadas of Camargo’s Domestically Chicano #2, a photograph taken of his mother’s kitchen table. Camargo captures these aesthetics beautifully with a kind of loving attention rarely given to these items, but which instantly evokes a sense of home and affection for viewers like me, whose mothers also keep the supermercado’s calendar up on the wall long after the dates have passed. It is this detail of the supermarket calendar that makes me think of the outside force of gentrification as it might act on this scene, the fragility of our kitchen tables full of the food we love. As people get pushed out, the businesses we frequent suffer and it gets harder and harder to find the things that are ours. We go from having a few stores that carry all our favorite tastes of home to perhaps an ethnic food aisle in an overpriced grocery chain we can’t afford.

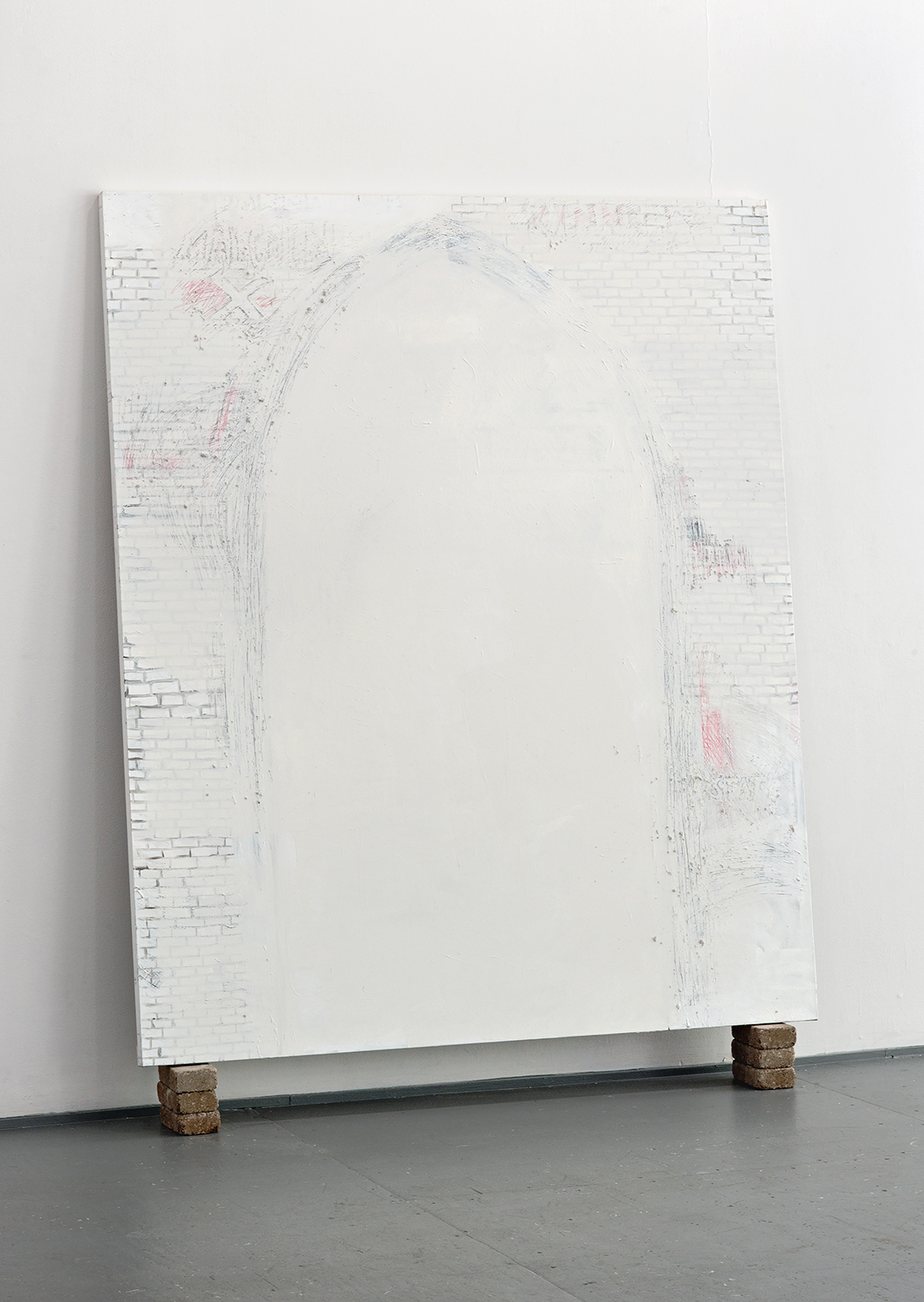

Haerim Lee’s pieces Whitewashed: All of Mankind and Whitewashed #1 – #5 chronicle both the destruction of Bill Walker’s mural “All of Mankind,” which was whitewashed in 2015 in an attempt to sell the church it was painted on, and the ongoing anonymous resistance to the whitewashing, as people have chipped away at the white paint. Lee’s two large panels evoke the physical space of the arch that Walker’s mural is painted in with surrounding brick detail and the rough thick layering of paint. One panel shows the arch completely filled in with white paint, the outline gesturing at what once was. The other panel shows the mural partially revealed, the outline of a group of four figures of different ethnicities embracing each other, reminding us, along with the framed photos of the spots where the paint has been removed, that the mural is still there. Her other paintings in the show, The Chicago 21 #1, The Chicago 21 #2, and New City, which form a triptych, show Mayor Richard J. Daley and city planners/architects looming over a model of Chicago. The paintings, based on actual photographs of meetings about the Chicago 21 Plan, are meant to lampoon the city’s powerbrokers, but I find them more disconcerting than anything. Men whom I have no real control over stretch out their hands and command neighborhoods to be wiped out. The way none of their faces are fully visible emphasizes that these actions are not limited to the historical time and place of their source photographs. This is how things are done in Chicago. The image of the hands of politicians assuming godlike power over the model of the city feels all too connected to Lee’s other paintings in the show, the destruction of an expression of man’s highest potential on a house of God. Gentrification is at heart a project of resegregation, an attempt to reverse white flight. It is no wonder that it claimed such a powerful mural, an image of people of different backgrounds sharing space together in unity. Lee’s pieces remind us that despite the efforts of the powers that be, at least for now, that mural, that symbol of unity, is still beneath if we scratch the surface.

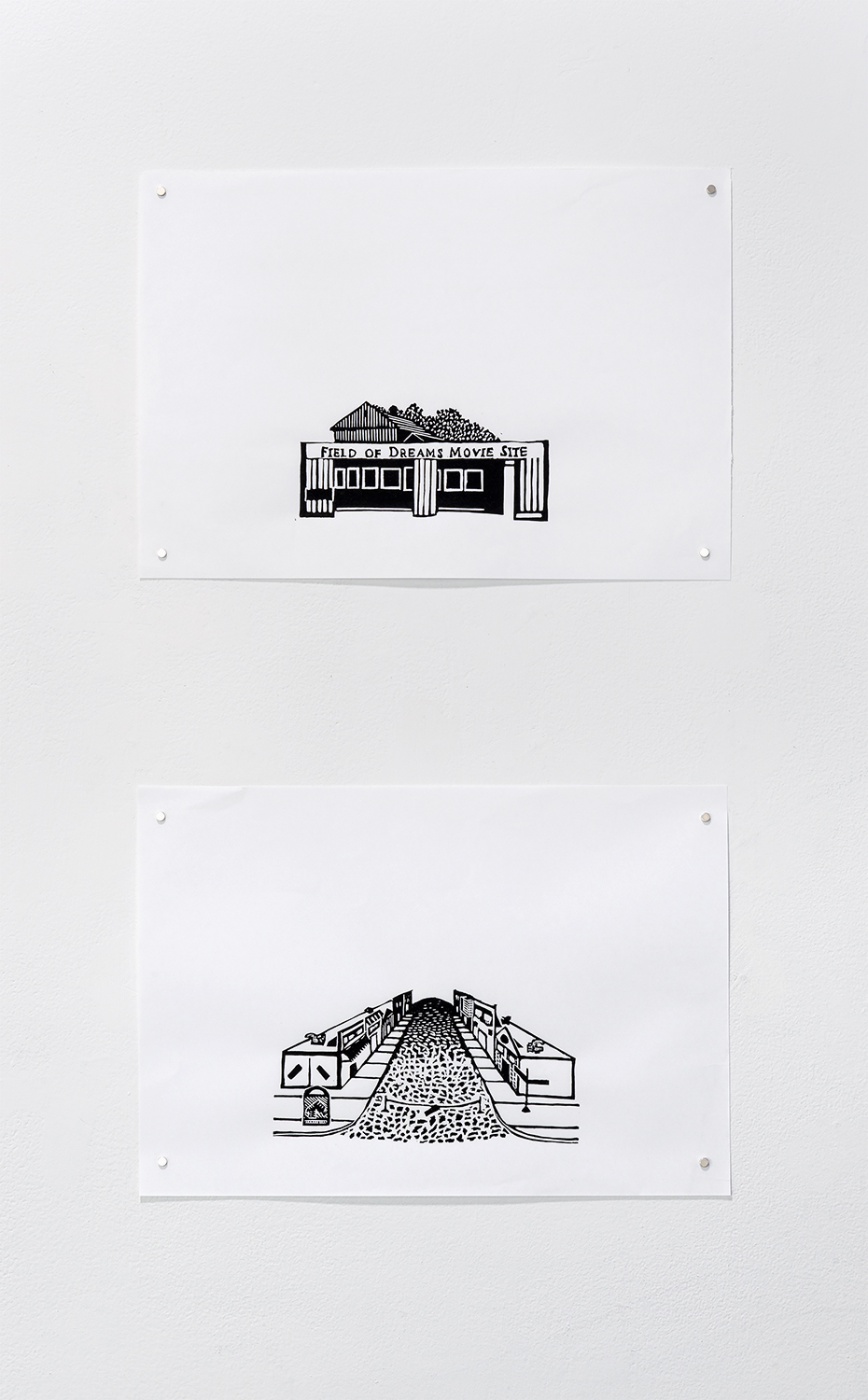

The show moves between interior and exterior spaces, between city and rural small town life, exploring the tensions that mediate our political lives and archetypes. Alejandro Waskavich’s Untitled (Midwest Panorama) stretches all along one of the walls of the exhibition, an endless field all too familiar to those who have driven through Illinois’ cornfields. The density of Chicago’s skyscrapers contrasts with the endless flatness, the sparse population of the rest of the state. The cornfields, the small town business district we can glimpse in Waskavich’s Main Street USA, they inhabit something we are told is “the real America,” something we are told those of us far from the fields can’t understand. This place of endless nostalgia that celebrates colonial aesthetics as something it will never let go of, endlessly dotted by antique stores selling relics to passersby. Waskavich’s prints outline this imaginary place of white identity politics, giving few features and letting you imagine a 1950s-esque row of white-owned businesses. Maybe all the business owners alternate between looking like the dad from Happy Days or Ron Howard as he appears now. Linoleum cuts and their line work lend themselves so perfectly to archetypes. But the Main Streets I’ve seen in Illinois have more than their fair share of immigrant-owned businesses and I can remember their outlines clearly as I look at this print. There’s something about those afflicted with white nostalgia that maintains our erasure even as we stand in front of them. If my business is next to theirs on Main Street, are they in the “real” Main Street while I am not? Or does my presence mean that the “real” Main Street must be somewhere else?

Camargo’s pieces Rasquache Intervention #1 -#7 shows tear-away fliers advertising businesses and apartments in the Southwest Side of Chicago. The signs are sometimes scrawled in handwriting, all cheaply made. Gentrification pushes out these sign makers, their businesses, the not-yet-too high rent on some of the fliers, the Spanish language. Camargo’s Cultura a la Renta echoes these signs, complete with the scrawled writing, and highlights the politics of their aesthetics with his own political messages. “Sell out Your Hood” one sign says. “1-800-FUCK-ICE” spells out the number of another. And Alderman Danny Solis’ office number is given out on the one that says “We Buy Homes for $$$$ Where People of Color Will Be Displaced.” The signs are big, bold, and loud, and there’s something heartening about the idea that as both the powerbrokers of the city and the dwellers of imaginary Main Streets are imagining a whitewashed, cornfield monotonous place with no sign of us, we’ll just keep making bigger signs.

Featured image: Detail of Cultura a la Renta by William Camargo as photographed through the gallery window. Three large scale tear-away fliers with hand scrawled messages, two in English and one in Spanish, hang in the foreground with two more visible behind them. Image courtesy of Greg Ruffing.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.