Born out of frustration at the country’s current political state and feeling unsafe to protest, fiber and social practice artist Aram Han Sifuentes began making fabric protest banners the day after the 2016 Presidential election. During her residency at the Chicago Cultural Center, she presented the Protest Banner Lending Library where the public could make, donate and check-out protest banners at no charge. The ongoing library invites people to support movements of dissent through making something with care: dynamic banners on novelty fabric that proudly wear slogans such as “Multi Culti Cuties Unite,” “Too Cute To Be Binary,” and “The Future is Female and Brown.” Hundreds of banners later, it is still a practical resource for organizers and activists who need the assistance and encouragement. Since then, the library has been presented and activated at Alphawood Gallery in Chicago and is currently at the Pulitzer Foundation in St. Louis, where Sifuentes is an artist in residence this summer.

Some of the most prominent banners read: “CHAPTER ONE: LOVE YOURSELF,” “ALIENS WELCOME,” “NO WALL,” and “LOVE RESISTS.” Photo by eedahahm.

The Protest Banner Lending Library was an act of catharsis and solidarity for the artist, bringing people together during a time of confusion and unrest, but it also opens up an important question: is it the responsibility of people of color and other marginalized folks to put themselves and their bodies at risk during this fraught political time? And, what are other ways to participate in protest or demonstrate resistance? Sifuentes prods us to reconsider our positionality within entrenched systems of power.

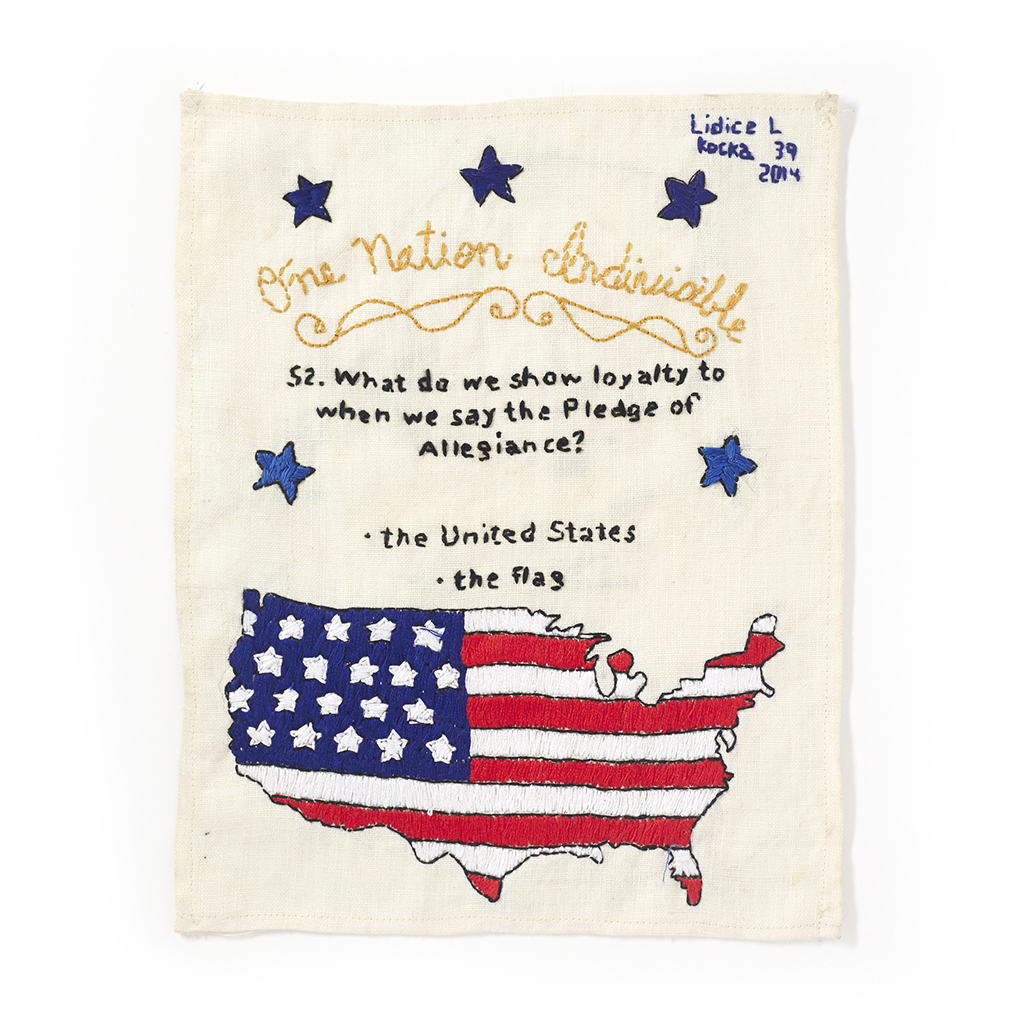

Another of Sifuentes’ ongoing work taps into samplers, which is a piece of embroidered fabric that is intended to demonstrate or test skills in needlework, typically made by women or children during the colonial period. The US Citizenship Test Sampler is a long-term embroidery project where the artist works with different communities of people to stitch the study questions and answers to the civic U.S. Naturalization Test in the form of samplers. Each question and answer is sewn on a piece of fabric that is slightly smaller than a sheet of paper, usually by one individual (although some are made collaboratively) who adds decorative stitches as well as their name and age and the year they made it. Sifuentes, who also stitches many of the samplers, then sells each one for the current the cost of taking the exam, currently $725, and works with non-citizens to fund their test.

In producing these works, Sifuentes’ chooses to work with groups of people in recurring workshops over several weeks to help them technically learn how to stitch, which is already a time-consuming process. She works with a range of communities, including individuals who are preparing for the test themselves, and for whom these workshops become a study session. US Citizenship Test Sampler as a work exists on various levels – in its teaching, collective-making, displaying and selling – each articulating important conceptual inquiries around the role of art, artists, and art institutions within our sociopolitical systems. I first encountered part of this work in the exhibition A Matter of Conscience (2017) curated by Assistant Curator Mia Lopez at the DePaul Art Museum, which acquired the nine samplers exhibited for their collection. Here, a museum purchased works that directly assisted nine non-citizens in their pursuit to become citizens.

The efficacy of Sifuentes’ work is layered, yet tangible. She commits to deconstructing power structures through incremental change using education and craft, two practices that are often marginalized in the contemporary art world. Through redistributing resources and knowledge, Sifuentes builds platforms for exchange and learning without glorifying participation for participation’s sake, the potential pitfall of socially engaged art and/or social practice since its the rise and formalization over the last two decades. She prioritizes empowering the Other and the disenfranchised by centering their voices and claiming space with them. And, while optimism is part of the work, it is the criticality of her practice that makes the work purposeful.

Dissenting through craft and within craft is central to Sifuentes’ work. Craft is not only a formal, material, and historical vehicle for her projects but it is a lens through which she encounters the world. She challenges colonialist approaches to craft, such as relegating non-western craftspeople to the fringes of the art world and labeling them artisans and not artists, and pushes back on conceptual investigations of labor in contemporary craft from a privileged, white perspective. She asserts that just because one spends a lot of time making by hand it does not automatically make it labor. Labor necessitates a critical understanding of the market conditions in which one is afforded the time and space to hand-make in a society where everything is manufactured.

Sifuentes’ practice extends into writing and criticism within this trajectory of disrupting the white, colonial spaces and systems of craft. In her essay “Steps Towards Decolonizing Craft” for the Textile Society of America website, she writes, “the deeply rooted colonialist frameworks of craft have just begun to fracture. It is our job to break open the cracks and continue to question, reveal, and abandon the colonialist spine upon which the craft discourse is built.” The essay takes the approach of working together to deconstruct the craft field, resulting in a number of steps to rupture, become accountable, amend our language, question the lineage of power and so forth. The text is radical because it is of practical use, and it moves us toward an equitable sensibility and methodology. Sifuentes’ experience as an immigrant Woman of Color informs the way she contextualizes labor and collectivity in craft, rejecting poetic, abstract gestures of resistance. Instead, she produces systems and spaces that help us fight the white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy one step at a time, but with care and agency, which is imperative during times of social and political unrest.

Featured Image: “Protest Banner Lending Library,” 2018. Aram Han Sifuentes holding a banner that reads “TRUST BLACK WOMXN” on a rooftop. Photo by Virginia Harold. Courtesy of the Pulitzer Arts Foundation.

Lynnette Miranda is a curator and writer who focuses on the social and political role of contemporary art, critically examining social practice, contemporary craft, performance, and new media work. She is passionate about centering artists and practitioners of color, not only through representation but through building support systems and the redistribution of resources. Lynnette is the Program Manager at United States Artists and has held positions as Creative Time, ART21, and the Art Institute of Chicago. She was also the 2016-2017 Curator in Residence at Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City.

Her writing has been published in Hyperallergic, Pelican Bomb, American Craft Magazine, Chicago Artist Writers, KC Studio, Informality, and This is Tomorrow, Contemporary Art Magazine. She has contributed writing to the exhibition catalogs Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp for Prospect New Orleans and Wanderlust: Actions, Traces, Journeys 1967–2017 published by MIT Press for the University of Buffalo Art Galleries.