What would the world be like if we eliminated prisons, surveillance, and policing? What types of alternative methods can we seek to pursue justice? What systems can we set in place to encourage people to come clean about their wrongdoings? These questions are at the center of the prison industrial complex (PIC) abolition movement, which aims to dismantle violent systems founded on oppression and inequality, including imprisonment, surveillance, and policing. These questions are also ever-relevant in Chicago, a city with a long history of racist police violence.

Do Not Resist? 100 Years of Chicago Police Violence, a recent community-based, artist-led multi-site exhibition that took place across Chicago at the Hairpin Arts Center, Roman Susan Gallery, Uri-Eichen Gallery, and Art In These Times, presented artworks that dealt with Chicago’s history of police violence. The artworks focused on specific victims and incidents of police violence, shifting the dialogue to question the PIC more universally. The final event of the exhibition-related programming, “The Aesthetics of Abolition in the 21st Century,” brought together Mariame Kaba and Sarah Ross to discuss the narratives presented in the exhibition in context of abolitionist movement building. Mariame Kaba is a curator, educator, and community organizer who works to end violence, examine and dismantle systems of imprisonment and policing, and promote transformative justice. Sarah Ross is an artist who, on her website, describes her multimedia work as exploring “ issues of access, class, anxiety, and activism,” highlighting her collaborative work on projects such as Compass (part of the Midwest Radical Cultural Corridor), Regional Relationships, Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, and the Prison and Neighborhood Arts Project.

Throughout the “The Aesthetics of Abolition in the 21st Century” discussion, Ross and Kaba strung together personal accounts of their experience as organizers, explanations of their own visions for how the arts play into the abolitionist movement, and thoughts on more universal questions about art, aesthetics, and visual communication. Kaba noted that oftentimes when she’s explaining the PIC abolitionist movement to people, they quickly fire back, “Well, what is your solution?”– as if to say, if she doesn’t have another system in mind to replace prisons, there is no point in critiquing them. Kaba explained that finding a solution to these systems of violence is a collective process — it takes more than one person to find the alternative — and that the arts are crucial to this process, as they allow us to build empathy and reimagine a world without prisons.

In the discussion, Ross dove deeply into the characteristics of abolitionist artwork: it is experiential, it is felt deeply by viewers, and it uses effective tools to challenge us. She noted that abolitionist artwork is often made collaboratively with people inside prisons and with other organizations working with a similar mission. Ross also pointed out that abolitionist artwork uses a range of visual vocabulary and depth; that these artists don’t just create an image that fits a certain campaign or activist moment, they really expand it and push boundaries from their own creative point of view.

Interesting questions came up during the dialogue concerning an artist’s intention or connection to abolitionism when thinking about a piece through an abolitionist lens. Kaba explained that although she is doing abolitionist work, she is inspired by artwork and artists that have no connection to the movement. The example Kaba highlighted was Claude Monet’s paintings of waterlilies. She finds that she is personally inspired by Monet’s work in her own practice as an organizer, but recognizes that the artist probably never intended these pieces to inspire abolitionist work. She proposed that artists who never intended for their work to be viewed in relationship to the prison industrial complex can be just as relevant or meaningful as artists who explicitly deal with those themes.

Another crucial aspect of the discussion was Kaba’s take on Black Lives Matter protest chants, some of which advocate for locking up violent police officers. Kaba stated that these chants are song-like and should be considered artworks in their own right. However, she added, the chants calling for the imprisonment of police are not in the spirit of the PIC abolitionist movement, as they are looking to prisons as a means of justice, while the PIC abolitionist movement sees prisons as a tool of oppression — one of the very things the Black Lives Matter movement aims to dismantle. Similar questions were brought up during the Q+A portion when an audience member asked about the intersection of the #MeToo movement and abolitionism. Kaba again reiterated that looking towards policing, prisons, and surveillance tactics to bring justice forward against sexual assaulters was not in line with the PIC abolitionist movement, as those systems reinforce violence and oppression. Instead, she offered up ideas of restorative justice systems, which create incentives for wrongdoers to come clean and be accountable, as a feminist approach to justice.

Do Not Resist? 100 Years of Chicago Police Violence was curated by the For the People Artists Collective, a radical group of Chicago-based artists of color. They see their duty as creating work that uplifts and highlights struggle, resistance, liberation, and survival within and for marginalized communities and movements locally and internationally. This group of abolitionists, cultural workers, artists, and organizers actively envision a world without prisons or police.

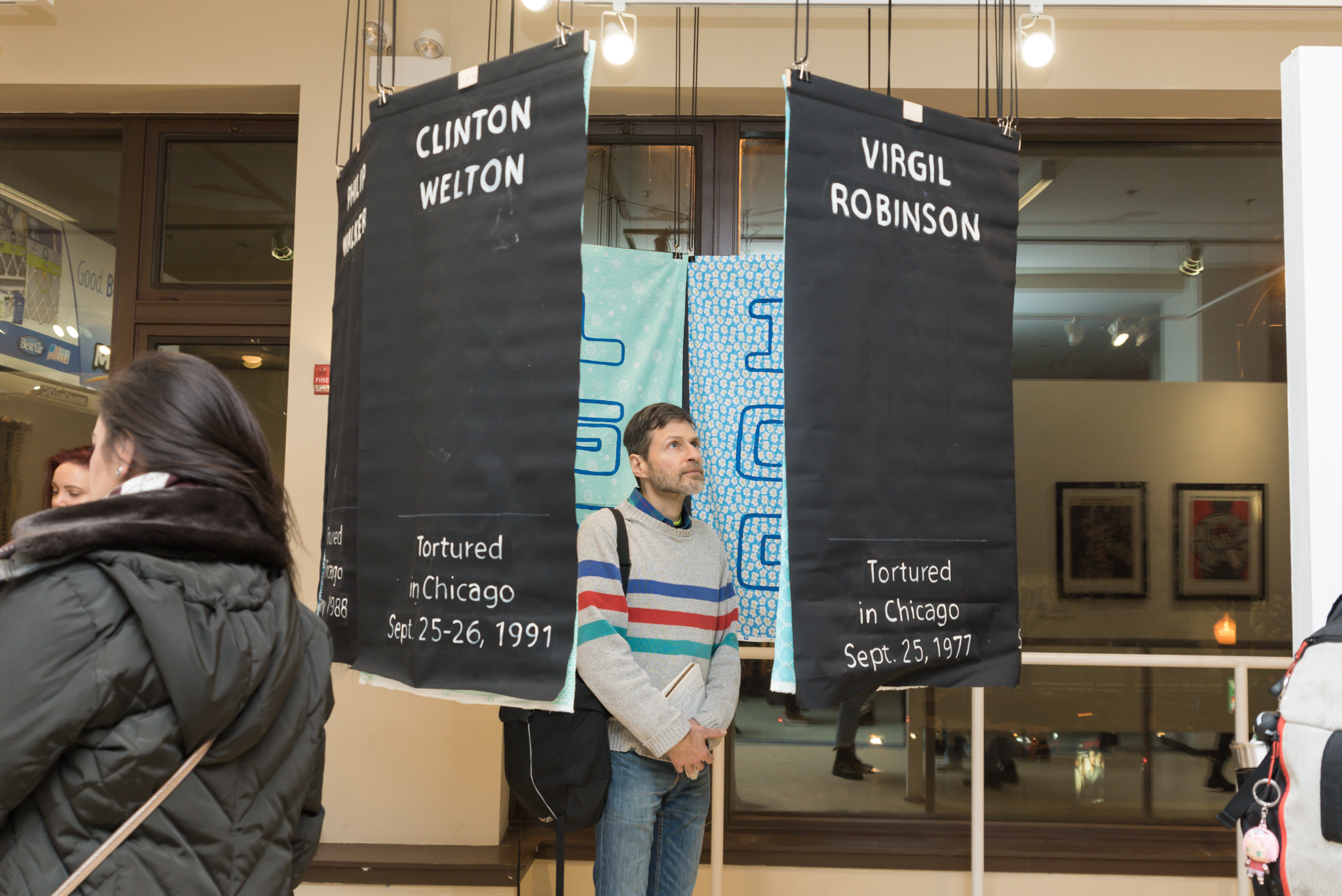

Featured Image: “Pillars of Resistance,” an installation by Chicago Torture Justice Memorials. Between 1972 and 1991, Chicago Police Department commander Jon Burge tortured over 125 African-American men. Victims, families, and communities came together to seek justice through an unprecedented reparations legislation in 2015. This piece commemorates both the decades of torture, but also the deep friendships created by the collaborative action of seeking justice in this instance and into the future. Photo courtesy of Sarah-Ji (#DoNotResist Curation Team Member).

Emily Breidenbach is an arts administrator with experience working at museums, education centers, and non-profits. She is currently the Assistant Director of Marketing and Enrollment for Continuing Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and has previously managed strategic communications for the Krannert Art Museum, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, and the Museum Education department at the Art Institute of Chicago. She has a B.F.A. in Art History from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is currently pursuing an M.A. in Arts Administration and Policy at SAIC.

Emily Breidenbach is an arts administrator with experience working at museums, education centers, and non-profits. She is currently the Assistant Director of Marketing and Enrollment for Continuing Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and has previously managed strategic communications for the Krannert Art Museum, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, and the Museum Education department at the Art Institute of Chicago. She has a B.F.A. in Art History from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is currently pursuing an M.A. in Arts Administration and Policy at SAIC.