This interview took place as part of an initiative occasioned by the first Chicago Archives + Artists Festival, held at the Chicago Cultural Center in May 2017. The festival kicked off a series of in-depth artist interviews, including this one with D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem, which will be contributed to the Chicago Artist Files at Harold Washington Library. This series of interviews was conducted with a group of artists, curators, instigators, and organizers who we believe are essential to the history of Chicago art. The interview with Denenge was conducted by Sabrina Greig and is excerpted below.

In addition to this smaller group of Sixty-interviewed artists, a call was put out to ALL the city’s artists: #GetArchived! The core of the free festival was a pop-up archive processing center staffed by Sixty Inches From Center and volunteers. Many partners lent their time, resources, and high-res scanners(!) to this endeavor, including LATITUDE, the Visualist, and Read/Write Library.

Sixty Inches From Center is excited to be continuing the Chicago Archives + Artists Project with support from the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, which will allow CA+AP to commission three new projects pairing archives with artists over 2018. As this year’s events unfold, we will be sharing last year’s interviews and continuing to reflect on the value of artist’s stories.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project serves as a laboratory for artists’ engagement with special collections, as well as a pipeline for the community preservation of artists’ archives. We want to find creative ways to care for an ever more accessible, playful, and diverse city-wide compendium of artists’ work, process, and ephemera. We believe in the power of artists telling their stories in many voices, on many platforms, past, present and future.

Read the full interview with Denenge here.

Sabrina Greig: Your home studio is a really magical space with lots of details. There’s something to delight the eye everywhere you look and what feels like a mixture of cultural references.

D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem: Ever since I can remember I’ve been reading Dr. Seuss and mystical, magical stories that my parents collected for us, and now as an artist and educator in Afro-Futurism, I bring that engagement with science fiction and other worlds to my practice. We’re in a beautiful moment of Black joy right now with the release of Black Panther which is beyond monumental on every level. It represents Black space, Black light, Black worlds, Black futures, new visions beyond our imagining of what is possible. I’m beyond thrilled that the publication of this interview coincides with the release of the film! This film, this mythology, all of the elements of this are connected and rooted to generations of foundation laid. I’m proud to have been part of that, to have nurtured scholarship and artistic production within the world of Black speculative creativity. One year ago, I offered a new course Superhero Self [at SAIC] in large part to create a space where students could identify their superpowers and build new bodies of work in formerly uncharted territory and media, and to offset the horror of what had just occurred politically some months before. The work students developed was brilliant and moving, deeply considered and presented. It’s amazing to be looking back a year later and to see where we are now, as individuals, communities and as Black people especially within the United States.

My parents were also really invested in seeking out and supporting African authors and I have many of those books today, now being passed on to the next generation. I loved reading about witches, especially, which was a little incongruous with the religious space we were in, but now as an adult and teacher, I’m excited by the fact that I envisioned then exactly what I’ve become and can bring this knowledge—largely indigenous holistic, earth-focused traditions—into the space of academia, a kind of decolonizing.

Growing up rurally in early childhood, I’d build things from stuff that I found, little environments and designed objects. And I’ve always been very fastidious in arranging spaces and feeling like my personal success or well-being was very tied to the physical environments that I was in in terms of how they were arranged and how I was moving through them especially given how much we moved from city to city or cross-continentally. So that has translated into engagement with design, installation and construction, and design solutions for the most part.

SG: As I look around your space, I see a lot of handwork and painted and patterned surface. Do you consider yourself a painter?

DA: Not so much painting, though I do enjoy it and really want to spend more time at that especially drawing. When I design for clients, they often will frame the sketches I create and the drawings have even melted the hearts of fairly stoic dads who might just be present to wield the checkbook in client meetings. For me, painting was always a means to decorate something, for adornment, surface detailing, or as part of a sketch or drawing. I’ve mainly always liked building things. One year–this is way back when and this is in the time when kids’ toys were real toys not just made of plastic–I think it was for Christmas or a birthday, my sister who’s younger than me, she must have been maybe five or four, was gifted (by our very handy renovator mom) this little wooden toolbox with all real tools, miniature size. For real. It had a lathe, it had a saw, it had one of those old-school hand-crank drills, but all functioning, like an actual blade in the lathe so you could plane teeny-tiny little pieces of wood. [Laughs] She never really used it but I remember being so envious of this and trying to get her to trade for it (which she refused). Life was wild in those days…

I love working with my hands; I can’t talk without gesturing or building words in the air. I dream in these strange synesthetic sculptural forms that are more sensation than anything else. I’m very much a sculptor, very much attuned to space; objects carry a lot of weight for me and I’m super-sensitive to the energies that objects carry. It’s one reason I really appreciate Marie Kondo’s Konmari space cleansing movement based in the notion of whether objects “spark joy” or not. I find this quite different from a lot of decluttering and design methods based in the U.S. that seem to be infused consciously or not with a very Puritan idea of the object being bad or negative—rooted in the belief of humans as good or bad, really—as if one is letting go of objects because of shame of ownership or acquisition which I guess is all part of the capitalist system: it makes you want it but also feel guilty for wanting it or buying it. What I find so refreshing is that her practice seems to be rooted in an aesthetic that honors the object as having a life or energy of its own with its own path in the world. Instead of shaming ourselves for having things, we can learn to see things are entities independent from ourselves that have their own rituals, gestures, and lives, as entities that enhance and bring new dimension to our lives in every form. It feels to me quite connected to a lot of my experience and studies in African ritual performance traditions–which I also teach and include in methodology–in terms of the object’s function within and beyond its role as object. I’m writing on this more extensively, too, for In The Luscious Garden.

As far as my artistic career with teaching, creating ritual performance, design for clients, and site-specific projects, it’s very much about how can I use my hands as a healing tool. It starts first with my own healing because I want first to be a grounded and whole being in a state of peace and balance within myself, and facilitate not just my own ideas but serve as a kind of conduit for the client’s vision, for their hopes and dreams to flow through into the crafting of the piece itself. The piece is kind of activated by that and then becomes a kind of a totem or mnemonic device which is really magical.

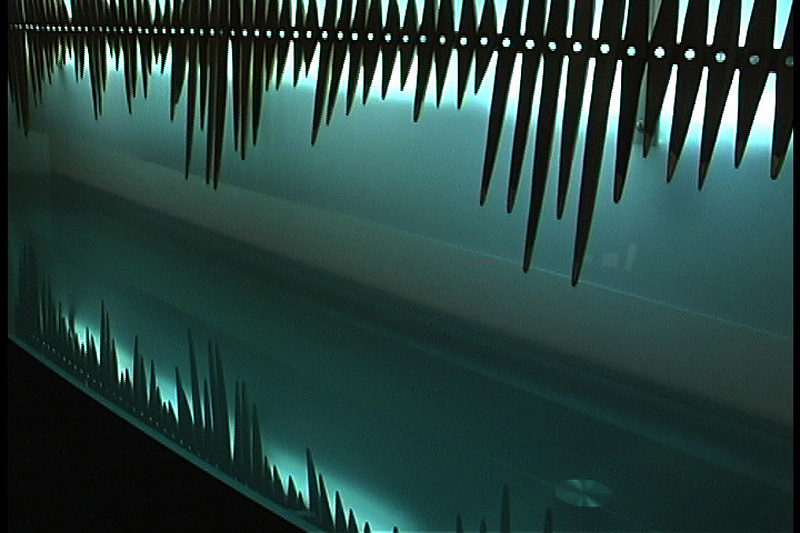

One of my earliest and first site-specific residential commissions was for a penthouse overlooking Navy Pier, with southeast Lake Michigan, south and west views. The work was highly personal with a central sound wave pattern of 65 individually carved 200-year old pine strands—for the year of the client’s birth—each tipped in gold leaf to represent his incredible business achievements. I remember carving those and sanding them–with the initial cuts on the band saw, I had to scrape the blade after each cut because the wood was so thick with resin. The fragrance was out of this world! It was beautiful old wood baked and cooled over centuries as part of a warehouse roof that my friend reclaimed before it was discarded. As a lighted piece, the color was decided based on gels representing his favorite color of Lake Michigan’s changing hues, and the piece was based on a soundwave of his voice speaking the lyrics: “don’t let your life pass you by.” It is one of my favorite works, one of which I’m extremely proud, and represents the joy I find in working directly with clients on site-specific pieces where “site” is not only a physical location but also the site of their history, memories, and desires for the future.

I hope to engage more projects like that in the near future. In fact, I will be creating a new configuration—or “constellation” of the Gold Nuggets For Us All! installation at Washington, DC’s Duke Ellington School of the Arts for founder Peggy Cooper Cafritz, joining a list of some pretty amazing and top-tier artists whose work will be installed all over campus as inspiration for the youth studying there. She purchased a Wan Chuku “mini” sculpture last year created for the Washington Project for the Arts—similar pieces which will be on view at my Arts Club installation on February 28—and it’s an honor to be included in a new book recently published about her collection!

For some years now I’ve been playing with how sound can shape a space. I experimented with sound force and space for Alter-Destiny 888 at The Lab for Installation+Performance in New York, inspired by Sun Ra. In fact, I’m realizing a dream on February 28, 2018 when I’ll be part of a panel on sound and space and debuting a one-night-only site-specific interactive sound installation Corpus Meum at the Arts Club of Chicago as part of the Architecture+Sound panel with Leigh Breslau and Ryan Dohoney. Super excited about that!

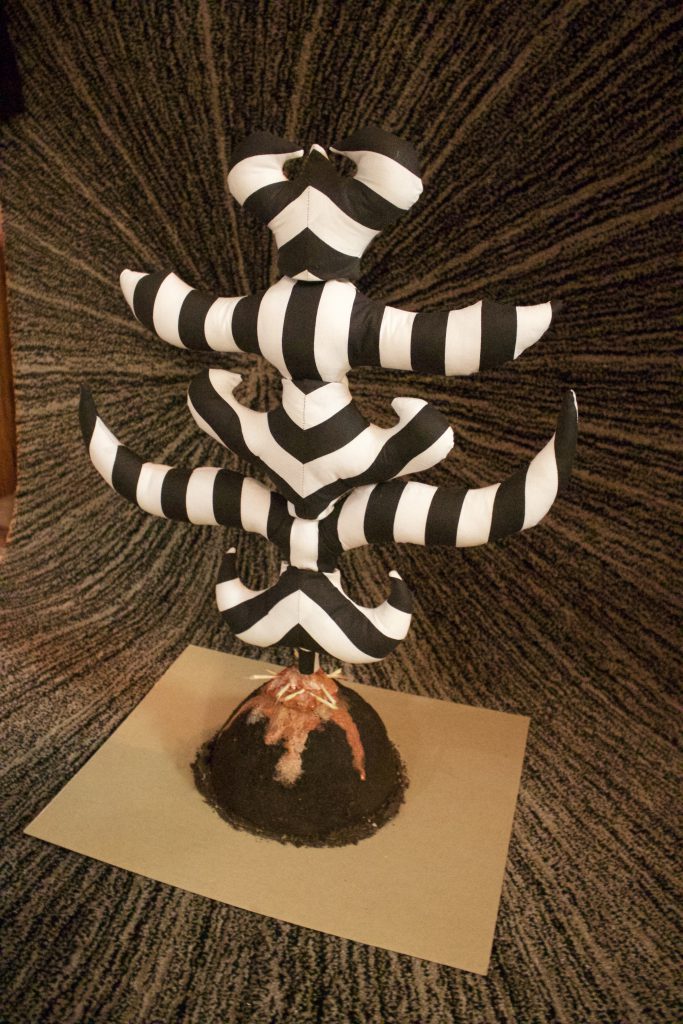

SG: Back to this idea of magic: I’m looking at these tall black-and-white striped soft sculptures you have on the wall over here by the leaf wall hanging. Can you tell me more about these and how you conceived of them?

DA: These sculptures were part of an installation at Oklahoma State University Museum of Art for a show curated by Moyo Okediji, PhD, an artist and African art historian who teaches at UT-Austin. The exhibition Wákàtí: Time Shapes African Art was all about performance, motion, and time-based work. Olaniyi R. Akindiya (AKIRASH) and I were the two artists commissioned to create large-scale room installations, and these were “trees”—or rather, the stems of yams growing up from the mounds—situated at four points to reference the idea of the four elements or four corners of the world. They’re quite tall–over ten feet when installed–and each one had a yam mound as its base so the tree seemed to be growing out of it. Tiv people are known as the yam farmers of Nigeria–African yams, not sweet potatoes–and where we live is a very verdant, rich farmland. Yams are life and Tiv people say if you haven’t eaten yams, you haven’t eaten, so my dad when we lived in the States if he hadn’t had yams in a long time would say, “I haven’t eaten at all!” Nothing counts as food unless it’s a yam!

So there’s this sense that the mound is growing from a kind of abstraction, very influenced by the book Where the Wild Things Are and my attempt to create a mystical wonderland playing with scale so that the visitor feels enveloped, overwhelmed, and also freed from the standard constraints. The black-and-white stripe is an homage to Tiv anger cloth (written like the English word “anger” but spoken as “ahn-gair” with emphasis on the “g”) which is a loom-woven cloth that’s given to you, the head-tie and the wrapper for women, when you achieve greatness. (My parents gifted me a set when I graduated from high school and moved to the U.S.) Tiv are known for beautiful design in woven textiles, basketry and furniture so I feel like that legacy continues in the work I do. Interestingly, given my cultural background, there is a real economy of form and embellishment, pared down and almost minimalist that is quite aligned with Dutch design traditions. I am really interested in exploring these intersections further in design and that’s another area I’ll be writing about more in the near future.

A dear student Hannah Green introduced me to dazzle camouflage some years ago. I love everything camo. I wear it all the time in every possible combination, I can’t get enough! It’s part of my new textile and wallcoverings design based on drawings inspired by Osanyin the Yoruba orisa of leaves and healing and my investigations into protection on spiritual and aesthetic levels in relation to my performance work. I was just floored by the way that dazzle camouflage resembled anger and the way that it allows you to shape-shift so I wanted to played with that in the museum space, to help the visitor shift from the outside world to another space and dimension with the disorienting nature of the dazzle and the scale. This environment, for me, it’s very warm, like being at home under these trees, and those who visit feel very comfortable here. It’s a whimsical space and I’m interested in how to bridge the idea of home-space and artistic-space–and I don’t necessarily mean home-studio–so that the space itself can contain those mystical, artistic elements in a way, not a sculpture that you just sit and look at but something that’s integrated.

As an NEH Fellow in 2014, I started working with references to the Yoruba orisa Osanyin, drawing leaves and creating a photo portrait series of all of the institute participants that to this day is one of the most blessed experiences I’ve had and the smoothest in terms of media–I didn’t expected it go smoothly since photography has never been an area that I really explored in great depth, and certainly not portraiture. I was investigating the idea of commemoration and the images of Osanyin, the god of leaves and healing, as he appears half human, half tree, hidden and often disfigured. Just like with the Sculpting Sound piece here in Chicago, the portraiture process was very organic and collaborative. The leaf drawings I turned into textile and prints which you see here in my home studio, and then for the Wan Chuku and the Mystical Yam Farm installation for Wakati at OSUMA, all flowing to the center clay pot with yam and fruits representing my Californian and Nigerian tree farming heritage with crystals dangling above to make the fruit seem like gifts from above which they are.

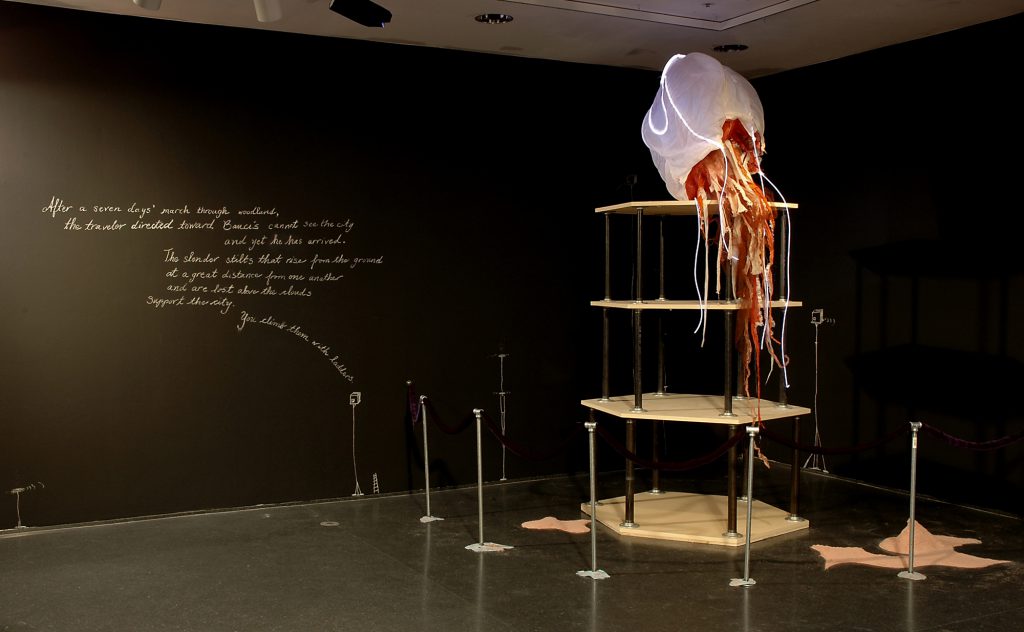

I’m also interested in the way that our perception of space can be altered by scale. And in terms of my ritual and mystical underpinnings, my work has been deeply influenced by reading and divination with Malidoma Patrice Somé, a Dagara shaman and scholar from Burkino Faso. I would say his autobiography Of Water and the Spirit has been one of the most influential texts for my work and life in general. I am interested in ancestral connection and in the Dagara understanding that minerals, rocks, rivers are all ancestors. This connection is something I’m cultivating much more in daily life and in the new courses I’m teaching such as the Knowledge Lab: Art+Ecology course for the SAIC Sculpture Department which I’ve shaped with a focus on healing, eco-feminism and indigenous practice. I do tend to sway toward culturally-specific tales of real-life mystical experience, stories that share inter-dimensional experiences or set the stage for experiencing what we may have thought was familiar in a new way. Rapunzel Revisited: An Afri-sci-fi Space Sea Siren Tale at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2006—my first solo museum show in the former 12×12 New Artists/New Work gallery—was based on the story of Baucis from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. So throughout, I take cues from writing whether it be stories or lyrics.

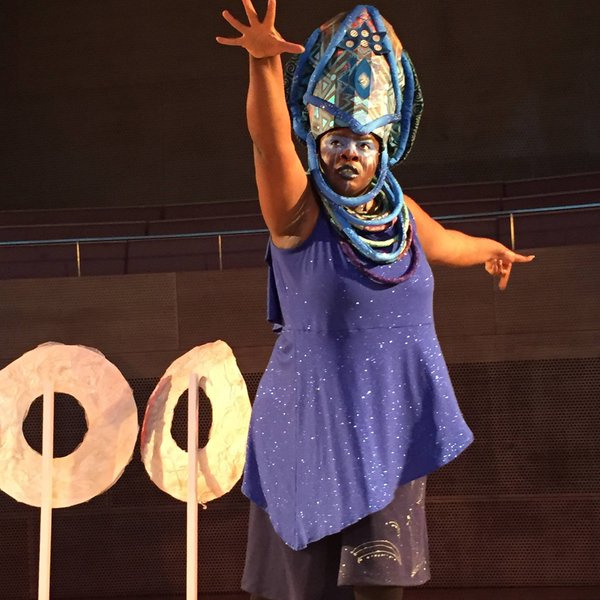

SG: I’m seeing a lot of headdresses. Where does that come from and what does that mean to you?

DA: Well, I teach a course on ritual performance and the survey of African art, and there’s a lot of focus on Yoruba art. One of the things that I really love about Yoruba aesthetics is the aesthetic of the cool–which is where everything we know about cool comes from–but basically, the head is the seat of all information, the seat of ashé: catalytic life force, to use Professor Rowland Abiodun’s definition which I really love (and he is very dear, being my first African ritual art teacher way back when at Amherst College). In Benin bronzes and works of art from Ife the head is very large in proportion, and you have the ori inu and the ori ode which is the inner and outer head. So definitely part of my interest in the headdress is connected to that. My work has always dealt with expressions of the mystical, ceremony and ritual whether in physical or virtual space or both, and the way that the garment and headdress prepare you and also prepare other people for what is to be done and set the stage for transformation.

In light of that, I designed headdresses, some costuming, and props for Honey Pot Performance’s 2016 Ma(s)king Her premiere at Pritzker Pavilion and it was truly magical to witness them in action. At one point, Felicia Holman looked as if she is floating above the stage. The costume is silk printed with a map of the Underground Railroad that I laid out into a pattern and turned into a cape with matching pageboy cap as part of her time-travel identity. And then they published it all in their first book with Candor Arts, and it’s just incredible to see the work in print after the experience of it in the theatre! One current project I’ll be releasing soon is a digital augmented reality interactive project and book with my brother Senongo Akpem of Pixel Fable. He’s an amazing New York-based designer who creates contemporary stories rooted in indigenous tales and aesthetics, and he speaks around the world about ways to ethically and successfully work with indigenous content in new media. We’ll be releasing Shipwrecked Sailor via a Kickstarter campaign within the year, and the costumes and design for this are really next level.

The more I started working with science fiction and Afro-Futurism, the more I felt like each of the costumes was a kind of investigation, not only of aspects of myself so much as these characters who revealed themselves to me, in a way, and of ancestral impulses and messages. And they revealed themselves not so much through philosophy but through the materiality of creating them…

Read more of Denenge’s interview here.

Featured Image: D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem photographed in the Garfield Conservatory Fern Room, 2017. Image credit: RJ Eldridge.