What distinguishes political art from propaganda? If we take the current exhibition of works by Aleksandr Zhitomirsky (1907-1993) at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) as our guide, then the line we traverse between the two is thin to the point of invisibility. Humanism & Dynamite: The Soviet Photomontages of Aleksandr Zhitomirsky is as nonpartisan as the “humanism” in its title suggests. Ironically, its subject could not be more partisan. On view are some hundred of the artist’s photomontages made during WWII as leaflets airdropped onto German troops and later as illustrations for Pravda. Zhitomirsky is a master of caricature, substituting animal heads for character traits in his posters of the archenemies of the Soviet state. While Nazis are easy (and fair) targets, the presentation of works slides from this morally black-and-white zone into one that is far grayer, drawing a thread between the two that is hard to follow. It is hard to follow precisely because it asks non-Soviet viewers, many of us American, to digest the USSR’s propaganda in the absence of any curatorial context that clarifies its historical origin and use.

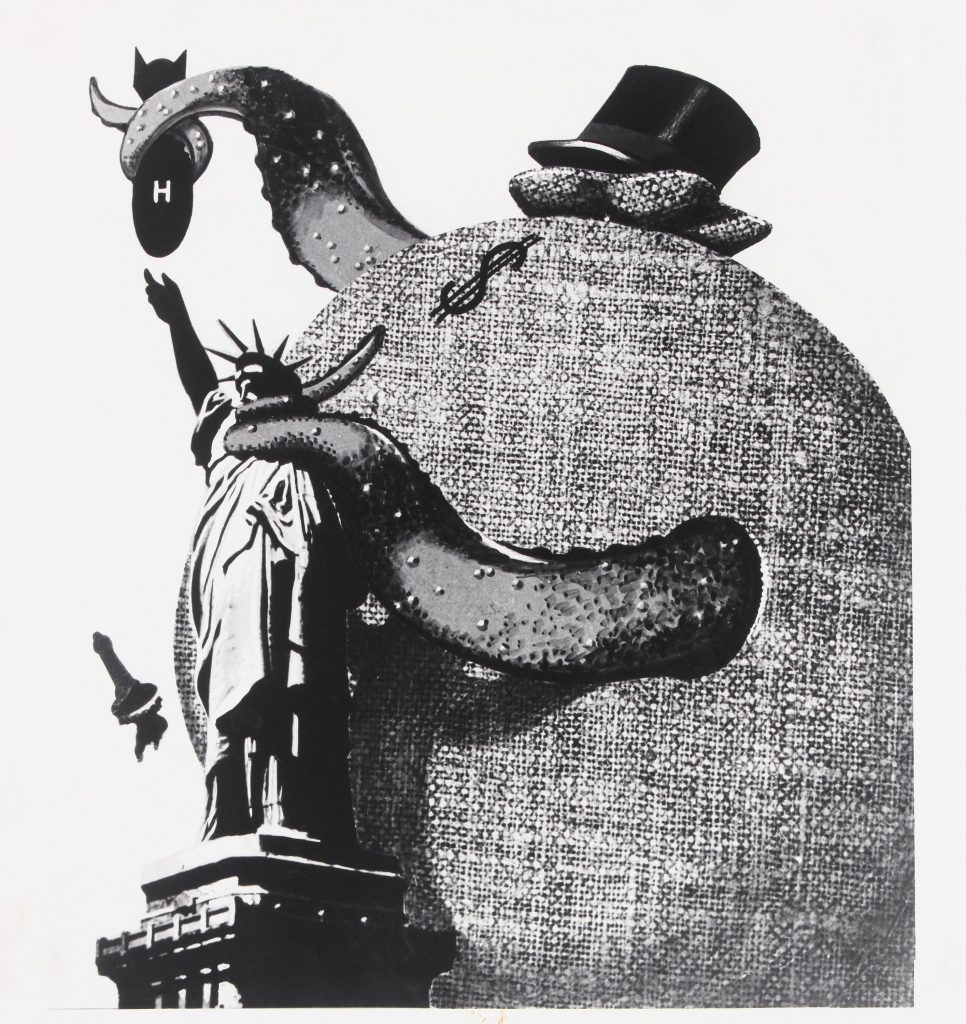

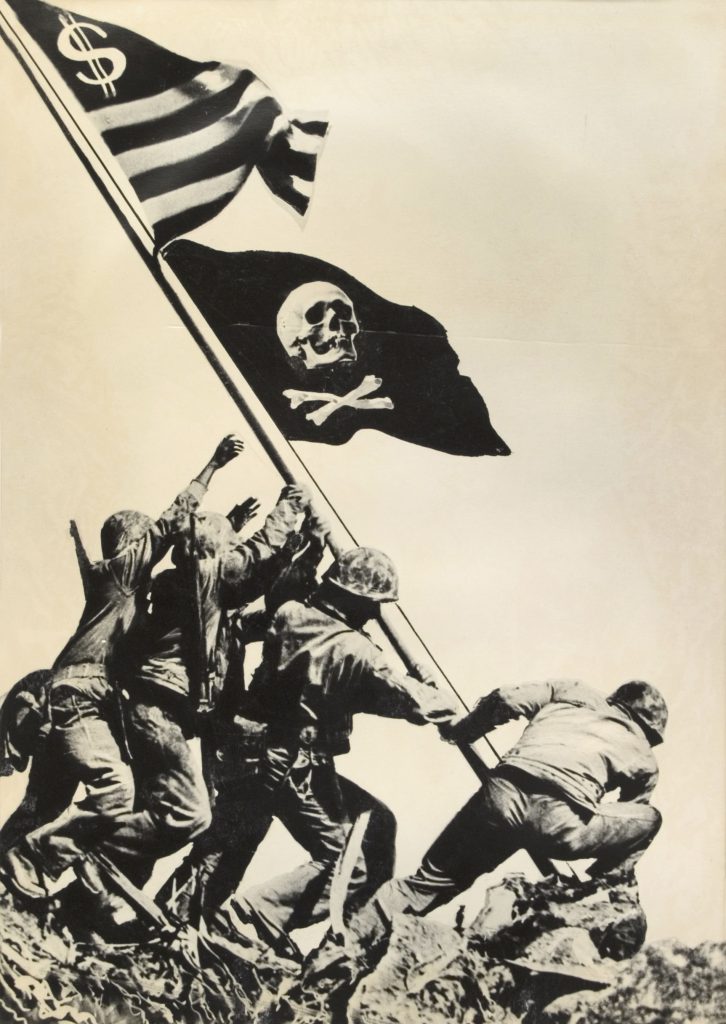

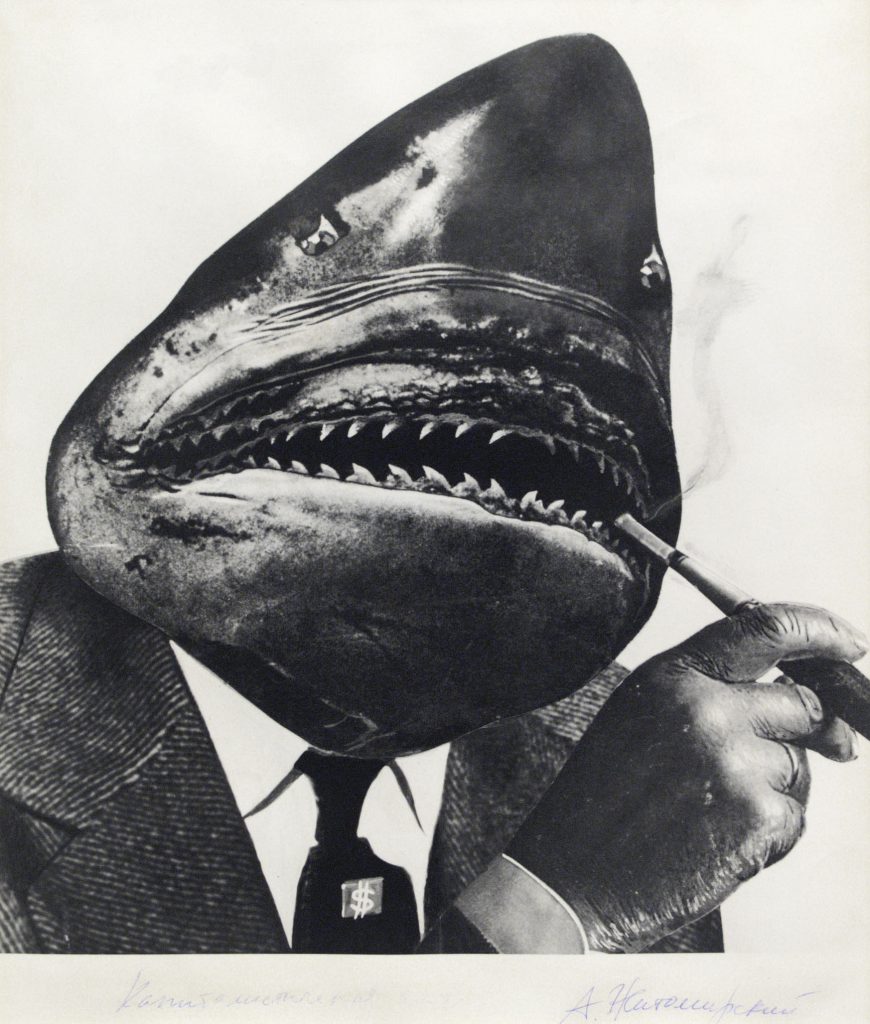

What’s more, it asks of us that we view that propaganda as political art, and not just propaganda. This is in itself a fascinating problem, one that raises uncomfortable questions. Is all political art propaganda, and should we therefore steer clear of it? Or is propaganda, as Martha Stewart would say, a good thing? Is propaganda simply political art when its craftsmanship is elevated to a certain standard? Humanism & Dynamite, in failing to address these questions, appeared to assume the answers. This is perhaps troubling for those of us who make political art, and yet do not think of ourselves as propagandists. But while I found myself in the company of other museum-goers who audibly praised Zhitomirsky’s “powerful message,” I felt certain that there must be others viewing the artist’s beasts of the Western world–sharks, chimps, scorpions, vultures, wolves, bats, tigers, and lions, an entire monstrous circus of the Cold War adversaries of the Soviet state–with my same skepticism.

While it’s true that Zhitomirsky’s photomontages are aesthetically clever (although, for my money, he’s no Hannah Höch), they are also somewhat hammer-(and sickle)-to-the-head obvious, like lines lifted directly from a Great Communist Handbook. This is the case despite the curators’ hands-off approach to historical contextualization. I can only see so many snakes in the shape of the dollar sign or fat cats of Wall Street smoking cigar bombs before I get the joke, so to speak. Subtlety is not the propagandist’s strength. So while the wall text dutifully notes that Zhitomirsky worked as an illustrator for Pravda, it need not mention that Pravda was the official newspaper of the Communist Party from 1912 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The visuals make that fact apparent. But perhaps it ought to do just that anyway.

Instead, the introduction to Humanism & Dynamite declares that Zhitomirsky “made current events clear and memorable for millions of Soviet readers…” Yes, his message is certainly crystal clear, but then I am not sure if it is his message at all. Propaganda is most effective when it is not perceived as being such, but rather confirms an individual’s preexisting axioms on an emotional level below the radar of awareness. Perhaps that is why Zhitomirsky’s works are so powerful or explosive to some. They are more like sucker-punches than reasoned argument. But because his photomontages are in fact examples of propaganda made under and for the watchful eye of the Soviet Union, a fact left unmentioned by the curators, they are not exactly paragons of artistic freedom. The views in Zhitomirsky’s photomontages belong to the Communist leaders. Whether their message is also his own cannot be determined.

Perhaps it is this fact that separates Zhitomirsky’s propaganda from the political art of ACT UP, Barbara Kruger, and Martha Rosler, among others, whose work was made in direct defiance of the State’s official policies? I would hope so. And yet something in me does not sit easy with that conclusion, as I am keenly aware of my own bias in favor of the political messaging of all three. Perhaps in propaganda, as in art, we see what we want to see after all?

Of course, while some propaganda may be accurate, that is not its aim. As a viewer with deep sympathies with Black Lives Matter (BLM), I stopped at Zhitomirsky’s photomontage of a black man hanged from the Statute of Liberty. That message, like its reference to lynching, might be obvious, and it might be inflammatory, but it nevertheless seems necessary to point to such deep and violent hypocrisy in the land of the free, no matter the artist’s motivations.

I know full well that propaganda is not after truth, facts, or even snippets of something we might call reality. Whether that is the ambition of political art in this our postmodern age, I cannot say. But my hope is that political art, like Zhitomirsky’s version of the Statue of Liberty, speaks truth to power, and does not merely amplify the voices of the powerful. In the context of the civil rights movement of the 1960s or BLM today, Zhitomirsky’s work does the former. In the context in which he in fact lived and labored– despite its notable absence from analysis in the exhibition at the AIC–he was the mouthpiece of a totalitarian state. And I cannot let this lens slide from view, despite my own susceptibility to some of Zhitomirsky’s works. I suspect the curators were not so assiduous.

Featured Image: Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. The Voice of America, 1950. Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Robyn Day is a graduate student in the photography MFA program at Columbia College Chicago and former arts critic at Art New England, Big Red & Shiny, and WBUR’s The ARTery, Boston’s NPR news station.