This is part four of a five-part short story series. Read part three here.

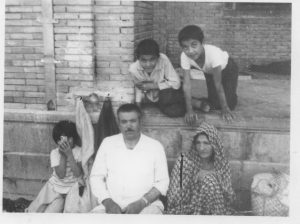

Monavar was born from a Turkic mother and a Persian father. She had never seen her father. She borrowed mother’s last name, which is/was frowned upon; such a thing never happened in Persia. Her mother was a rebel with a gun, walking on the roof as long as Monavar remembered. Monavar was a rebel in a different way; a gun-less rebel. She was married to her cousin at the age of ten. I had never seen grandpa. She hated him.

Monavar’s hair was white. Once, it turned blue when a black color fought her whiteness. She was full of love for her kids, and my father was the one who she relied on the most. Monavar was the light of our home. She kept secrets in the chest of her heart. In a chest that was part of her dowry, she stored many scarves, and uncut fabrics. She smelled like rose water and she never learned that a polite way of calling a bra is not “boobies’ support” but it is corset.

Monavar was a white light in a blue house. Short grandma had more light than the moon in the sky. She was married to her cousin, a rural man that was a Wiseman of a village. Monavar, the city girl, did not like the outskirts; she visited the city constantly. Once she went home and found a woman in her bed. Her bed was still fresh from her own scent when another took over. A fresh widow was taken to Monavar’s husband’s bed to get revenge on the dead husband. The widow became grandpa’s second permanent wife. Monavar had servants. One of the servants had a daughter who was tall, young, and beautiful. She became the third wife of grandpa soon after. Monavar left; never looked back. She lived in the city with her kids without a divorce.

Monavar joked in shameful ways. Mom never liked the “un-ladylike” jokes, but Monavar was a fierce woman. She saw no shame in sexuality. She never allowed a man in her bed after grandpa, she thought they smelled. Monavar told us girls to get boyfriends, to enjoy life to the fullest. She told me to wear fresh clothing every morning, to wear makeup everyday.

A big backyard was a platform for many parties after the war. Warm summer nights were tolerable with a slice of a watermelon that Monavar picked out and her son bought. Saturated water with sugar with a dash of melted saffron poured over cold water was in glasses. Freshly washed lettuce was served in the backyard to be dipped in sekanjebin*. Summer sunsets were time to water flowers.

Monavar’s favorite habit was to wash the mosaics with cold water in hot summer afternoons right after she watered the flowers. She then put a long wicker down on the floor next to the wall. Her hands were as rough as her favorite wicker; both brown, and unpleasant to touch, but full of love in their every inch of weave.

My most favorite days of my childhood were when Monavar took me to mosques with her. She often had me sit to the end of the row so that I would not mess up the entire row’s prayer. As she was praying I was looking at her and was observing the mosque: all women, all covered. These women were covered with their veils that were long pieces of fabric. These covered women were separated from the rest of the world, by a white big fabric that was held with poles in the middle of the mosque. A division, a separation, a liberation, a segregation, an oppression was ruling the space. I closed my eyes days after days in the mosque, and imagined who is behind the Curtain. I imagined naked men; I imagined a harem full of men. I imagined a party full of men drinking Shiraz wine; I imagined it all.

I watched her bumpy hands pray to Allah for many hours of every day to give health to her sons. I held those uneven hands on the way to mosque, I kissed them when I said goodbye to her when I fled the country. I remember her face when she told me: “This will be the last time you see me darling; I will die the next time you visit home.” I never saw her again.

*Sekanjebin is a traditional Persian syrup made of sugar, water, mint, saffron.

Read Division – Part Five: Esmat here.

Soheila Azadi is an interdisciplinary visual artist based in Chicago and Iran. Born in the capital of Islamic cities, Esfahan, Azadi absorbed story-telling skills through Persian miniature drawings since she was nine. Azadi’s inspirations come from her experiences of being a woman while living under Theocracy. Now residing in the U.S. Azadi is dedicated to transnational feminism with a passionate devotion to the ways in which race, religion, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity intersect. Azadi currently teaches at Oakton Community College while she is an artist resident at Hatch Projects.

Soheila Azadi is an interdisciplinary visual artist based in Chicago and Iran. Born in the capital of Islamic cities, Esfahan, Azadi absorbed story-telling skills through Persian miniature drawings since she was nine. Azadi’s inspirations come from her experiences of being a woman while living under Theocracy. Now residing in the U.S. Azadi is dedicated to transnational feminism with a passionate devotion to the ways in which race, religion, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity intersect. Azadi currently teaches at Oakton Community College while she is an artist resident at Hatch Projects.