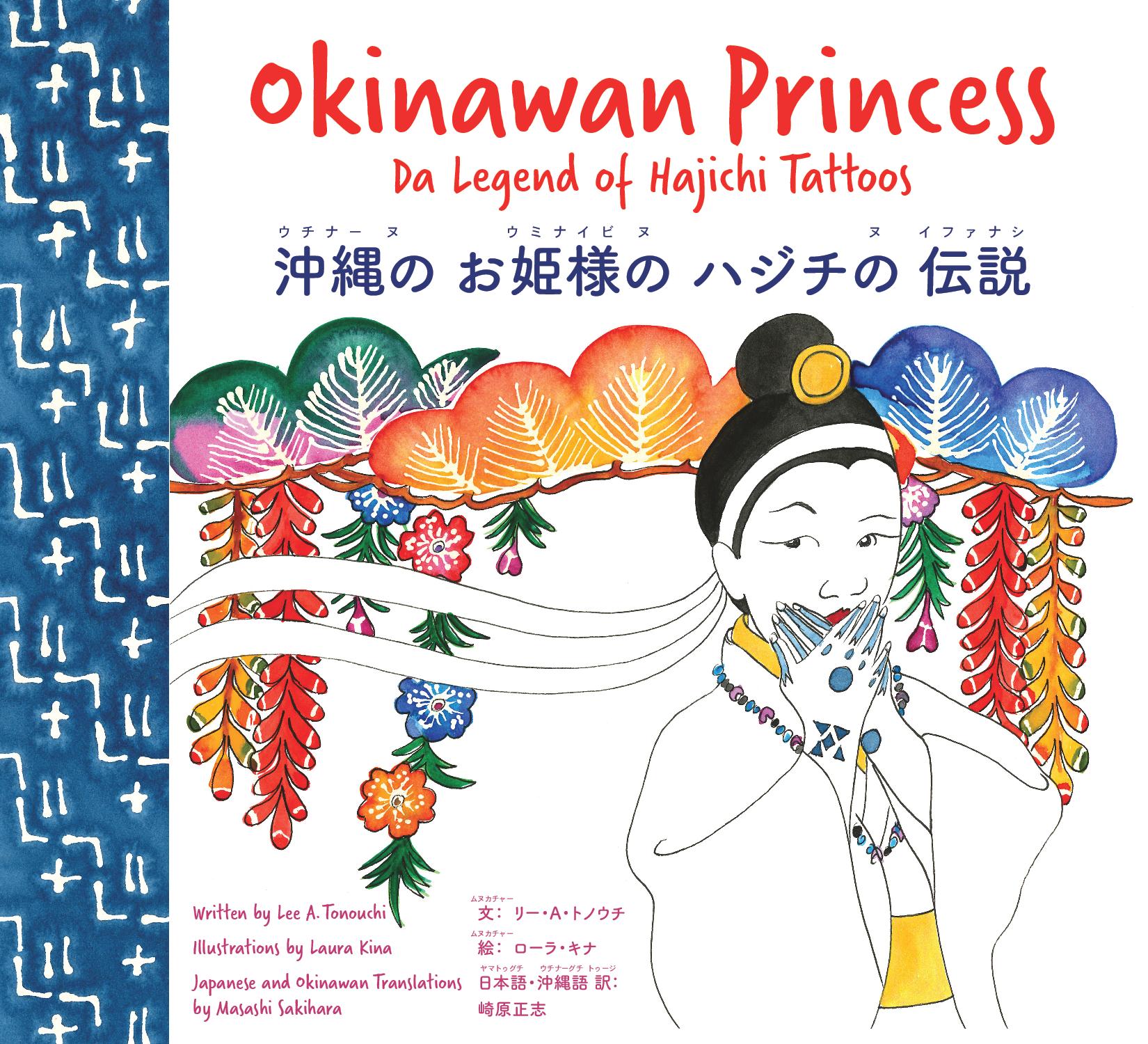

Laura Kina is an artist and professor of Art, Media & Design at DePaul. She founded the school’s Asian American Studies program, which has since become a Global Asian Studies program. She runs the Asian American Art Oral History project, which collects oral histories of Asian American artists, organizers, and participants of Asian American arts and cultural organizations in the Midwest. She co-founded the Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies and has edited two anthologies, Queering Contemporary Asian American Art and War Baby/ Love Child: Mixed Race Asian American Art. She is also the illustrator of the upcoming children’s book, which will be published in March 2019, called “Okinawan Princess: Da Legend of Hajichi Tattoos,” which is a trilingual feminist fairy tale set in set in Hawai‘i and Okinawa, written in Hawai‘i Creole by Lee A. Tonouchi and translated by Dr. Masashi Sakihara into Uchinaaguchi. Kina is the lead curator of the Midwest module for the Virtual Asian American Art Museum, which is a large-scale digital humanities project developed by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University that aims to be a resource for scholarship on Asian American Art. Complete with interviews, geospatial tools, high quality images, and scholarly essays, the VAAAM is on the cutting edge of making both art history and the digital humanities more accessible and comprehensive. As part of Art Design Chicago, the Midwestern module will be focusing on the transnational lives and work of Japanese American Chicago artists Ray Yoshida, Michiko, Itatani, James Numata, and Yasuhiro Ishimoto. In her own work as an artist, Kina collects stories and images and transmutes them, highlighting what might otherwise be forgotten. I got a chance to talk to Kina about her work documenting Asian American Art History, the Virtual Asian American Art Museum, and her artistic practice.

On October 3, 2018, Kina will be at the DePaul Art Museum for a launch party and conversation for the Virtual Asian American Art Museum, which is being held in conjunction with the exhibition Yasuhiro Ishimoto: Someday, Chicago. She will be discussing her work along with Jasmine Alinder, Associate Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, John Tain, Head of Research at the Art Asia Archive in Hong Kong, and Karen Patterson, Curator of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

UPDATE: The Virtual Asian American Art Museum is now live and can be seen here and Kina’s module on Michiko Itatani can be found here.

There can be a lot of information on the art taking place on either coast, while information on art history of the Midwest can be harder to find, especially if you are from a community whose history has been traditionally excluded from mainstream institutions. Kina said that the geospatial elements of digital humanities projects like the VAAAM lend themselves to exploring space and movement, and when it comes to Asian American Art in particular, this lends itself to exploring transnational aspects.

“I’m not sure if this is too confusing to think about this but, I’m originally from the West Coast, my family’s originally from Japan, and then we went to Hawai’i, and then the West Coast, and then Chicago and I think a lot of Asian American lives are very transnational because of that matriculation. So space or how we think about geography informs our communities. And it’s not like Asian Americans just arrived in the Midwest, but there are larger populations whose histories have been written on either coast, but in particular in the arts. So that’s where my focus has been. And on a very granular level I was thinking about who were some of the first artists and teachers that I knew when I moved to Chicago, who had an impact on me. They were my teachers Ray Yoshida and Michiko Itatani. So in one way this is just an act of love and a gesture to the people I really admire, you know? Wanting to write them into history in its own way.”

Kina said that the Midwest-Chicago module for VAAAM grew out of the Asian American Summer Institute at New York University’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute in 2012 that also helped launch many other projects. (To see a complete project history click here.) Since 2009, she’s been working with her students to do interviews on Chicago’s Asian American artists and through the Asian American Art Oral History Project and “this idea came up to create a larger project … So through NYU, we started meeting with the Smithsonian and the Getty Research Institute,” who already have modules that they’re building on New York art as well as on art of the West Coast. Kina said that she got scholars, curators, and collectors together to being a discussion and that since she is a part of the Japanese community, that’s why their first modules focus on Japanese American art. “It’s the community that I have the most access to. But this is a scalable project … so there are other curators and projects coming up.”

I asked Kina why they decided it should be a virtual museum. She said that, of course, funding for a physical space can be an issue. She also said that the Smithsonian has already been doing a lot of things with virtual exhibitions and programming. “There is already this history and strength of taking something that could at first be perceived as a weakness, not being able to have actual institutions, that in your curatorial practice can really lead to a wider audience, can be very accessible, and can move around. It can be for kids writing a school paper all the way to researchers who are specialists. We were aware of scholars and artists across the country that you really have to be an expert to know and we’re trying to find a way to make these collections and materials accessible to the public.”

Video: “Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values,” 1 minute 52 seconds. In this short promo by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, curator Karen Patterson explains how Yoshida’s art functioned to shape art history in Chicago. Courtesy of the museum.

The launch and panel discussion at DePaul on October 3rd, which is happening in conjunction with the Ishimoto exhibition, is a rare opportunity to see some of the work on this digital humanities project happening in a physical space. Kina said that Alinder and Tain would be presenting on the exhibition. “This whole catalog and the show grew out of what was originally first just going to be a digital humanities project. So it’s kind of fun that a real life brick and mortar thing happened along with a digital one.” She said that Jasmine had also been writing on James Numata for the module. Kina described Numata as a “vernacular everyday photographer” and said that they had found his archives in the Japanese American Services Committee. “ He documented post-war WWII Japanese Americans in Chicago. It’s just really fascinating to hear what people’s everyday lives were like in those years after Japanese Americans were forcibly incarcerated and then resettled in the Midwest. And it really tells a Chicago history but then also the particular Japanese American histories.” She said that Patterson will be presenting on her research for an exhibition of Ray Yoshida and his collections that she is now turning into a visual humanities project while she will be presenting on Michiko Itatani, who is currently a painter and teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago.

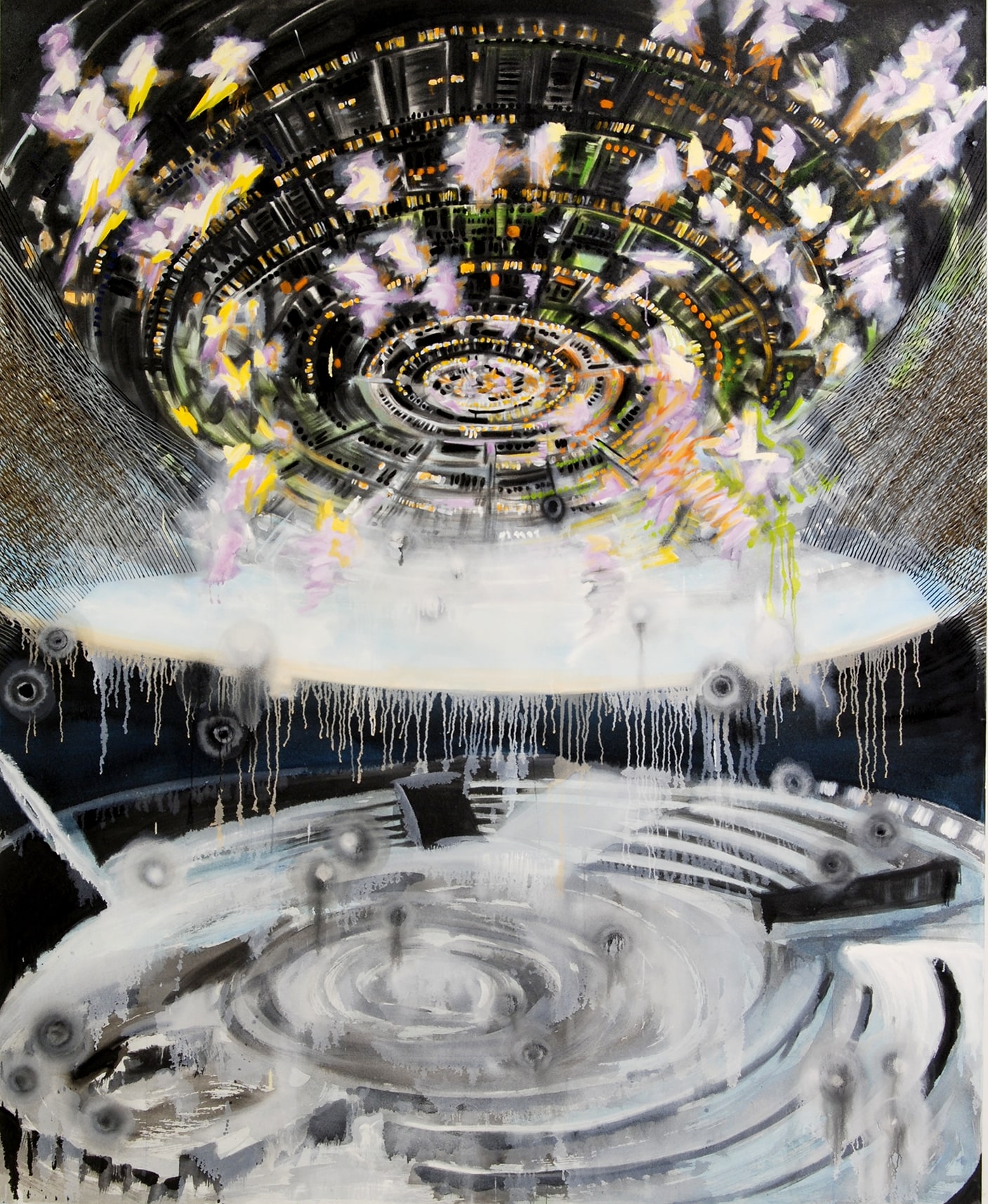

Itatani’s work is stunning in breadth and scale and for the ways it explores space, both physically and conceptually. I was really curious about how Kina’s work on Itatani’s module would be able to translate her work into the digital realm. Kina gave me a sneak preview of the module and I clicked around with Kina as a guide. She talked about the need to migrate platforms to Tome because of programming issues and the burgeoning digital humanities nerd in me resisted derailing the tour with my curiosity about functionality. The header for the module was a large image of one of Itatani’s works, whose size and intricacy really felt like it set the tone for the section. “If you scroll down and you see where there are sections that are red, like ‘Michiko Itatani – read more.’ And that can open up in there. So we’ll talk about her biography. This one is a timeline about acquisitions and publications. We cataloged all of her things, scanned them in and put them into a timeline.” Ultimately, Kina says that keywords will link different modules together. “Eventually we hope that people, teachers, users, can create curated pathways. So they may be wanting to learn about Japanese incarceration for example, they can put those keywords in and then different modules that are about that or paths might come together. So that you can look at information dimensionally.”

Kina said that the essay she wrote on Itatatani had grown out of years of email exchanges, visiting her exhibitions, studio visits, and recording her during an interview. In particular, the essay looks at two exhibitions that Itatani had in 2015, Highpoint Contact at the Zhou B Art Center that looked back on her work from the ’80s to the present and one that was a new body of work that she exhibited at her commercial gallery. The article is accompanied by audio clips from her interview and an image gallery. Kina said that she had originally envisioned herself in an organizing role, rather than a writing one, but that Itatani requested that she do the module on her. “I was really honored that she asked me to do that,” Kina said. “So this is just you know one artist and then I was also writing about her in this larger context of — she’s part of the post-1965 wave of immigrants. You know our very restrictive immigration laws changed. She’s part of that wave, Kina said. “And the artists that we’re looking at are coming from a different point in terms of Asian American or Japanese Americans history. So she is representative of women artists who came after 1965 to the US. And we know a lot about artists like Yoko Ono, who you know, came to New York, but not about people who decided to come to the Midwest. I feel like her biography is really useful in that way.”

But part of working on a digital humanities project like this can involve needing to resist flattening art history or leaving out context. “I think for me, particularly, writing about Michiko, one of the challenges is she’s an artist who literally wants to disappear. She doesn’t want her work to be read as a biography and she’s really resisted that, both being read as a woman and being read as an immigrant from Japan. And she would give me information and then take it back and say I couldn’t publish it. She doesn’t want the narrative of her life to be the way that we view her work. And everyone who’s written about it usually has a kind of orientalist description of her work. And so my challenge was to fend for it, seeing what her influences are, and then trying to do a close reading of her work in terms of her formal approach, where she’s traveled, what work she’s looking at, what literature she’s reading. You know, the context and philosophy and how is that entering her work so that it’s not some sort of flat, racialized reading of her work.”

When asked about the impact that Yoshida and Itatani had on her own artistic work, Kina said that it was really empowering to see Ray Yoshida’s work as an Asian American painter. She said that it was one of the only instances where she saw herself reflected in the curriculum, outside of an Asian American literature course. On a practical level, she said that they were both fantastic teachers when it came to learning how to paint and that she continues to be influenced by their interest in patterns, decoration, colors, and their approaches to experimentation and rigorous studio practices. She also remembers that Itatani once said something that stayed with her about not waiting around for someone to discover you, but to build your own network, your own places to show. “That influenced me to think about. Well, I could just with my friends start curating shows and making things, not waiting to get discovered. That small thing that she said as my teacher really propelled me to do a lot of what I do … We’ve stayed in touch over the years and she’s always been a source of encouragement.”

Taking Itatani’s words to heart, Kina has done a monumental amount of institution building. She has founded programs, an academic journal, led projects to collect oral histories, and edited two anthologies. When I bring this up during our interview, she laughs and says she needs to stop all that and get back in the studio. I ask her about whether she views any similarities between creating institutional space for the collection of marginalized histories and her own practice as an artist. Kina takes more note of the differences. As a curator, she describes her practice as “taking photographs, doing oral histories, looking at archives and using a lot of those materials to create bodies of work.” But when she is in the studio, she says, “A lot of times I’m working more intuitively, thinking about feelings and affect and the things that you can’t verbalize. So that’s my own practice. So then when I would go to an artist talk or try to get an exhibition opportunities to put it out in the world, it felt like I’m always having to start first with identity based descriptions and long explanations before I could even have a space to show the work and that was really exhausting and not that interesting. So I think that being an academic, why not create the world you want to be in? So I don’t know that there’s been a master plan but a lot of the things have been kind of organic.”

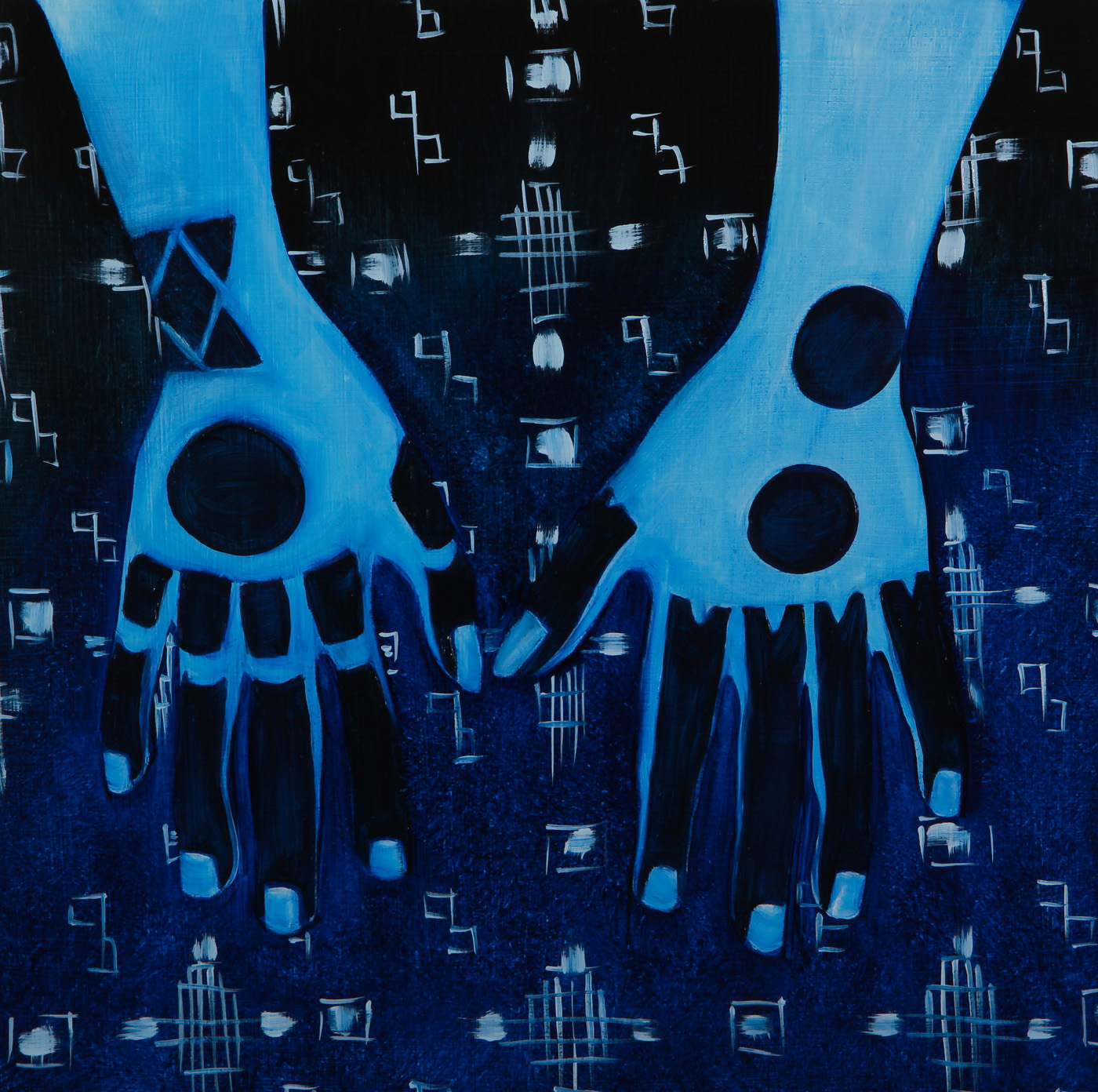

Her work illustrating the children’s book Okinawan Princess: Da Legend of Hajichi Tattoos also came about in an organic, serendipitous way. She said that in 2013, she was at an Association for Asian American Studies conference in Seattle where Lee A. Tonouchi’s book Significant Moments in da Life of Oriental Faddah and Son: One Hawai’i Okinawan Journal won an award for best Poetry/Prose. Kina said that Tonuchi is an Okinawan American author from Hawai’i who writes in Hawai’i Creole and sets a lot of his work against the backdrop of sugarcane plantation history. She was really interested in his work “since this is the same background and community as my father’s side of the family. So I decided I would have to contact him. A few days later, Lee was googling ‘hajichi tattoos’ and my artwork popped up and he emailed me to ask if I would illustrate a book he was going to write on Okinawan hajichi tattoos. The timing seemed to be more than a coincidence so I said yes!” In her show Sugar at Woman Made Gallery in 2010, Kina exhibited the “Hajichi #1 (Okinawan Tattoo)” and “Hajichi #2 (Okinawan Tattoo)” as part of a series where otherworldly blue figures recalled obake ghost stories and evoked Japanese and Okinawan picture brides turned sugar cane laborers. When asked about the process of visualizing stories that have been left out, she said that sometimes it was a matter of “working intuitively and not knowing why you’re going in a certain direction.”

Asked whether her work on the VAAAM has made her reflect on preserving her own legacy as an artist, Kina laughed and said that she is sometimes better at thinking of archival work for others than for herself. She said she doesn’t know about for her own work personally, but considers it more for community efforts. She said she was once part of the Asian American Artists Collective Chicago, which was founded by Anida Yoeu Ali and her then-husband Marlon Esguerra shortly after 9/11 and was very active until 2005. Kina said she was involved in the visual arts part of the group called Project A. “We worked with other parts of the collective to put on showcases and art shows for several years in conjunction with the annual Asian American Showcase that is part of the Foundation for Asian American Independent Media. At one point the collective had over 100 members and we had a theater group called Mango Tribe, a young authors group called YAWP! (Young Asians with Power), and Kitchen Poems was a writing circle. I also helped the group put on a spoken word and poetry summit back in 2003.”

Kina said that through her work on the VAAAM, she hopes to change the way that the main story is told in the Midwest. “It’s hard to be part of the scene here because … the focus isn’t international. Right now I’m working on a symposium along with a professor at Kyoto University that’s going to happen in Tokyo in December and it’s thinking about minor transnationalism and Japanese diasporic art. So I’m having these really fascinating discussions with scholars in Japan and Brazil and the US who are working on these issues. But I am not always able to have those here. It’s a wonderful place to live and work. And I have to believe there’s a lot of other artists here that maybe have that same experience of the Midwest.” It can be difficult to really feel like you belong in a place if you don’t see your community’s history reflected in it. Asked about the insularity of the Midwest, Kina wonders what it really takes to be of a place. “I think in some ways this project and even the oral history project in the Midwest is a way for me to feel rooted, like yeah, I live here! And even if someday I go back to the West Coast, I did my time. I moved here to study under the Chicago Imagists. I’m really informed by that practice of collecting and collage and pattern, an outsider mentality. So that, even if it doesn’t look like Chicago art, it’s definitely a Chicago practice. And then what Chicago has given me, that I wouldn’t have if I lived somewhere else is the ability to explore what I want to and that’s so important, about my ideas or what I’m doing in the studio. A lot of freedom.”

Shifting the Chicago canon was something that Kina was thinking of in particular with regards to Ishimoto, she said. “He’s a very transnational Chicago artist. Yet you always think of it as something more recent but going back in the history, you can find it. … Ishimoto was born in the US in 1921 and was an American citizen, but his parents were both from Japan and they returned to Japan shortly after his birth. He was raised in Japan for the first 15 years of his life but, according to scholar Jasmine Alinder, he considered Chicago his artistic home … Shortly after he returned to the US in 1939, he was forcibly incarcerated during WWII at Amache. This is where he learned photography. After camp, he was trained at the Institute of Design and studied under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. His post-war career was predominantly in Japan and he ended up moving back to Japan and revoking his US citizenship.” Kina said that Tain and Alinder’s exhibition and catalog explore Ishimoto’s liminal identity and his transnational career.

This was Kina’s her first digital humanities project and she said that thinking about how to work in this new format that would be added to later was different for her. “Thinking about keywords and how you’re just one person making a contribution and it’s scalable, so over time, the most important thing is really that structure. So things that will be dealt with in the future, I hope will help carry that logic, right?… And so you’re not just converting an existing essay, into an online format, but writing it in short, accessible, small paragraphs and that are interspersed with interactive media, so from the very beginning, thinking about writing and producing work in that way was new for me. And remember that I am an artist, trying to do this sort of editorial art history work so that also was new for me. And also Michiko’s work doesn’t have an identity-based focus, so for me it was a challenge to also seriously think about the practice, the instruction, or something else bigger than the biography. For me, it was really good to have those conversations.” Leaving that structure behind for others to add on to is part of what Kina said she ultimately hopes to do with her work. “I hope that my artwork and scholarship will be inspirational for the next generation and that I’ve been able to help record a history of Asian American art that will be useful in the future. I also hope that the structures I’ve helped build will continue to cultivate spaces for the next generation to build on or bounce off of.”

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org.

Captions for Michiko Itatani’s work were done as the artists requested. Images courtesy of the artist.

Featured Image: Laura Kina sits in front of a brightly colored painting of floral motifs. Photo by Kiam Marcelo Junio.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.