As many contemporary artists, arts organizations, and other cultural laborers continue a decades-long trajectory of reorienting their practices more deliberately towards and within the social world, forms and approaches have morphed through a collective re-imagining of the production, dissemination, and sociopolitical potential of art. These modes have sought to broaden access and participation in the arts, transform relationships between people, forge practices rooted in ethics as much as in aesthetics, and other similar gestures toward aligning art with notions of social justice and reform. Yet amidst this grappling, a number of unresolved riddles remain regarding art’s place in daily life: who is art’s “community,” and what exactly do we mean by “community”? What is art’s relationship to democracy? Can increased access to the arts also advance civic participation more broadly? What is the role of the artist in society? Can art and artists be catalysts for social change — and should they?

Such issues and questions reverberate through the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum’s current exhibition Participatory Arts: Crafting Social Change, which explores the influence that Addams and other social reformers have had on visual and performing arts in Chicago through historical and contemporary practices of bookbinding, ceramics, theater and performance, and art therapy. The show is structured by pairing current practitioners alongside objects and artifacts from the Hull-House Museum archives and UIC Special Collections relating to important figures and moments in the settlement’s history. In addition to the exhibition, programming has featured a series of workshops led by the featured artists, as well as a symposium that explored the historical legacies, and current potentials, of art to incite social change.

Founded by Addams and Ellen Gates Starr in 1889, the Hull-House symbolized reformist ideals of the Progressive era (1890s–1920s), and was part of a nationwide movement of settlement houses which, in many ways, sprung up in response to the exploitation and social stratification of the Gilded Age. Operating under the notion that art and education are vital components of democracy and community life, these sites offered resources and creative outlets for new immigrants and poor and working-class neighbors in their local area.

At Hull-House, Addams and Starr specifically integrated arts and crafts as ways to reunite “work of the mind” with “work of the hand” and combat the increased mechanization of factories, which further distanced workers from the fruits of their labor. A bookbinding studio was among a number of initiatives established at Hull-House to aid in this reconciliation. The resulting books as handheld mobile forms, in tandem with teaching binding skills as more dignified and unalienated modes of labor, became a means of disseminating information and furthered the founders’ important goal of making the arts more accessible to immigrants, women, and children.

This conception of the book medium finds contemporary parallel in the work of Regin Igloria, a multidisciplinary artist working across sculpture, installation, bookmaking, performance, drawing and collage. His practice often focuses on movement and the human struggle within particular places and landscapes. In 2010, Igloria founded North Branch Projects as a community space to teach bookbinding in Albany Park, first as a dedicated storefront and now as a roaming series.

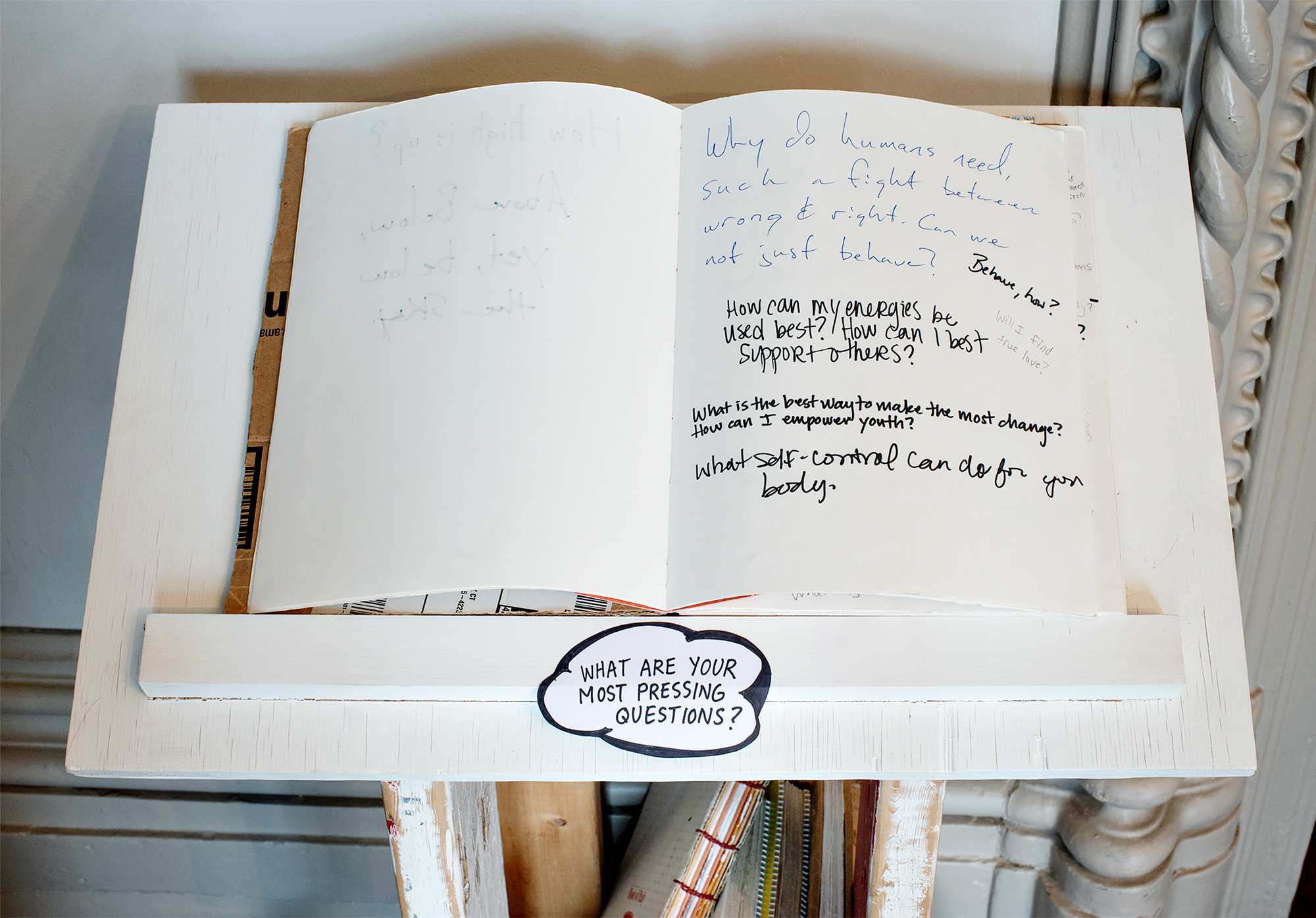

Their ongoing project Everything on Wheels, which is included in the Participatory Arts exhibition, uses handmade books on mobile pedestals as platforms for audiences to scribble their thoughts to different questions and prompts, ultimately assembling a collection of community voices.

I recently met with Igloria in his studio at Read/Write Library to talk more about that endeavor, neighborhood archiving, the origins of North Branch Projects, and more. This interview is part two in a three-part series (see part one here and part three here) of dialogue with artists featured in Participatory Arts, on view at Hull-House until May 2019. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Greg Ruffing: Are you originally from Chicago, or if not, how did you end up in Chicago?

Regin Igloria: I was actually born in the Philippines but moved to Chicago with my family when I was three. So I’ve been raised here in the United States, and mostly until I was in my 20s I was living in Chicago. And then I left Chicago to work at Anderson Ranch, and that was the first time I formally resided in another state. I spent a few summers there, and then went to school out east in Providence [at RISD] and then came back [to Chicago].

GR: And with that upbringing, and more or less spending the majority of your life here, has Chicago influenced you or influenced your practice in certain ways?

RI: Yeah definitely, especially the neighborhood of Albany Park, which I pretty much base all of the major philosophy behind North Branch Projects on. It’s all sort of devoted to that upbringing and what Albany Park represents in terms of the diversity, the working-class families, the real mix of identities that people have. Right now I think it’s mostly a Latino population in the area where I grew up, but Lawrence Avenue was dubbed “Seoul Drive” at a certain point because of all the Korean businesses that were lined up and down that street. And my classmates in grade school were from everywhere. It was pretty fantastic. I didn’t really realize the beautiful scope of that until I was an adult. I’ve always had a very interesting relationship with the contemporary art world, I think because of my upbringing in Albany Park. So I think about all of those issues and ideas constantly to this day, and my upbringing is definitely part of that.

GR: You’ve worked in a lot of different forms: 2D forms, obviously three-dimensional, and bookmaking and performance work. So I guess, taking stock of all that, are there certain threads that have kinda stuck with you over time?

RI: Oh yeah, sure. The most common thread would probably be the relationship to nature. I think having grown up as a city kid, and because of the financial and economic situation of my family, we never really traveled much outside of the city — in fact I don’t recall going anywhere except maybe Wisconsin Dells [laughter]. We just couldn’t afford it with the five kids. And so any sort of excursion to anything that represented what “nature” was to society — how it was depicted in magazines and TV and movies I had seen — was really exciting to me. And the North Branch of the Chicago River was sort of my first foray into “the wilderness” [laughter]. So of course I had a profound experience going to Colorado because that was the first time I’d really encountered mountains on my own. And just the beauty of it — I mean I literally had to pull over to the side of the road to wipe my eyes because it was so emotional and amazing and beautiful to me as a Midwesterner who constantly thought about that.

GR: Did Colorado change your practice in some way?

RI: Colorado sorta made everything very real for me. It hit me really hard because as blown away and mesmerized as I was by nature and seeing mountains, I was completely thrown for a loop by the lifestyle out there. I mean, they all had money, that was the biggest thing. You know, they had all this gear and equipment, and all this stuff to enjoy nature with, and I couldn’t afford any of that stuff so I was kinda torn. I was thrown into this world [in Colorado] because of art, but yet I couldn’t really participate in the lifestyle that people were living out there. And it all happened through Anderson Ranch because we’re right behind the ski slopes — and everybody is white there, and has a lot of money, and they’re grocery shopping in ski boots.

GR: And part of it too, like, there’s this relationship between leisure and consumption, and this wealthy white culture around the ski slopes, right? And I was thinking about that installation you did at The Franklin–

RI: –the hanging basket–

GR: –right, the hanging basket, and it was a bunch of, like, outdoor gear — and that’s a part of how this “experience” of “nature”–

RI: –yep–

GR: –that its mediated through consumerism in a way, right?

RI: Totally. And I think at that point when that show happened, I was living and working at the Ragdale Foundation, overseeing admissions and the residency program. But this is Lake Forest and it’s the suburbs. It’s not the mountains, but there’s this whole other level of the regard for nature and the manicuring of nature through wealth, basically. So again, art allowed me to live in that sort of environment. There’s no other reason why I’d be there. But the hanging basket, for me, symbolized the whole idea of kinda bringing nature to your property, and all these people having hanging baskets. I felt like I needed to be grooming nature in a kind of weird way. I needed to be planting things and be surrounded by foliage.

Although still all about money — I guess I could never get away from the idea that all these things I somehow wanted, I didn’t really need. So it was kinda this push and pull of needs and wants, being influenced by people around me — white people, and white culture, basically — I mean, let’s face it. And I think I didn’t admit that until after graduate school, which is a long ways to go about denying the fact that I had this brown skin and I’m just not gonna ever fit in that world, because of the way I look. So now I’m just thinking about it a lot more because of where we’re at socially and culturally, so you can’t help but just let that come out more in the work. I was just thinking about this again recently because of this teacher retreat I was facilitating. I was looking at some other potential sources to share with the teachers, and I was looking at a lot of the books on my bookshelf — and all these artists I had been looking at, they were all these white artists, you know, who were thrown in my face, and I didn’t think much about it back then [in graduate school]. And that stuff just wouldn’t fly today, you know?

GR: Yeah there’s been a lot more challenges to that canon.

RI: Completely. So now I’m going back and there’s a bunch of things kinda filed away that I haven’t revealed from 10–12 years ago that I had been thinking about and was evident in a lot of the research I’d been doing in graduate school, and these drawings I had been doing of these backpacks and gear and focused on outdoorsy culture. But none of that was blatantly about this frustration with how white culture had sorta permeated into my psyche and how much it had affected things I had been doing — not just as an artist, but as an arts administrator, as a teacher, as a human being, you know? And now it just seems like it’s starting to hurt a lot more. I’m starting to feel all of those things because I’m starting to see other people feeling it as well. So I think that’s part of the reason why I’ve gone to this format [books and zines] more to disseminate. And its definitely why North Branch exists, and it’s why my work has moved away from creating these hanging pieces that can be exhibited in a gallery to something that people who I grew up with in Albany Park would actually take the time to see.

GR: I wanted to ask you about that because I’m curious more about the origins of North Branch. It seems like North Branch was a kind of pivot for you, right?

RI: It was a huge pivot, yeah. And all that stuff we just talked about was a slow buildup to where I’d gotten to the point where I was completely frustrated with my relationship to the contemporary art world, because here I am in Lake Forest working at an international residency program where all these fantastic artists are coming in, and all these other artists and colleagues of mine are in the city — there was this divide between those two places. So I was kinda struggling with that, trying to get people to come visit me and see what’s going on and experience this residency, and at the same time trying to get people from Ragdale that I’m working with every day to come to the city to see the work I was doing. That was just the beginning, and then I’m starting to realize, I’ve been thinking about this my entire life because with my family, it would take a whole lot of energy and convincing to get them to come to art shows and visit galleries or museums regularly. Why is that?

My entire life I’ve been trying to convince myself that I’m part of this other world, or this art world, but I’m never gonna be completely part of that because my upbringing was completely different. You know, being from this working class family in Albany Park, and their priorities are not about going to see museum shows or galleries. Their priorities are about raising kids and getting them a proper education so they can get a job. They’re just trying to put food on the table and make sure their kids grow up healthy and happy. And that’s one thing I got from my parents is that I can’t deny how steadfast and true they were to that. They have me beat, completely! The way they approach life, the level of humility and grace on a day-to-day basis. And I’m so far removed from that because I’m always trying to, you know, experience this thing or grow in this way and make a particular type of work that’s going to have an impact.

GR: Did North Branch start as a storefront at the very beginning, or did that come later?

RI: Yes. So I was working at Ragdale and like I was saying I was frustrated with the polarization between these two worlds and I was trying to create some crossover. And I look back at the times when people actually did cross over — what did it? And I’ll talk about my mom again because this was a very significant moment: I had shown her an artist book I had done of these ink drawings of text pieces. She had looked closely at the drawing marks in these letter forms and noticed that it resembled the patterns of one of her houseplants. And I think that was probably the very first time we’d ever had a conversation about my work. It was a very short conversation–

GR: –it’s a start!

RI: Yeah! And she was willing to talk about something that obviously had resonated with her, so this idea of the book form, maybe because it wasn’t in the gallery or museum, it was in her dining room and she was able to touch it and flip through the pages. There was a strong connection. That book form itself becomes a solution to engage in conversation on a deeper level with somebody. So I felt, you know, there’s something to be said about this format that allows people to feel comfortable, that opens people up, that allows people to ask more questions, allows people to slow down. So I try to take my love of book arts, and my interest and experience in teaching, and just spending quality time with people, and that’s where this whole idea of “community binding” took place, like I’d like to be able to create a place where I can invite people in the neighborhood to make books with me and let’s see what happens. And, you know, for the most part it worked, but it came about in an oddly convoluted way. Nothing was instant, there was no “aha” moment when I had the storefront.

GR: Yeah, and it sounds like part of what you’re saying — even using the book as an example, and that story with your mother — is like, taking these things out of the sequestered zone of the gallery or the “art world” and trying to just bring it directly to people, right? So in that way the storefront makes a lot of sense as a kind of middle zone?

RI: Yeah, the middle zone was really important, and I don’t think it was actually very original. A bunch of people I knew were just trying a bunch of things, like home galleries. So creating this space that I purposefully did not turn into a white cube space was really important. In fact, the questionable state, the perplexing state I had presented to the passersby who walked up and down Lawrence Avenue every day from the train station, turned out to be one of the more important aspects of the space because people couldn’t figure out if it was a café or a copy shop. like, “what do you guys do?” And so making it obvious that there’s no clear answer to what it is, allowed people to safely or comfortable knock on the door or poke their head in, and then if I could show them a couple of books, then maybe we’d have a conversation or they’d stick around to see what I’m really talking about. And that was really the way I was able to pull people in off the street to engage in this process of making books. And it was as simple as showing people how to fold paper, and then if you stack together these folded pieces of paper to make signatures, and this is what makes up all the pages of this particular type of book. So people connected pretty quickly with that.

GR: How long did the storefront go for?

RI: It was a little over four years. It was exciting, but the finances kept being the thing that was draining, so eventually I had to close it and think about what it would evolve into. Because I knew I didn’t want to give it up completely. So it turned into a lot of pop-up situations, which was happening when we had the space too, and people were inviting me to teach different workshops at other arts organizations, schools, and museums. And it was nice, it really allowed me to work with such a varied group of individuals, from six-year-olds to retired people, and everything in between. And the nice thing too is that they weren’t artists or people in the contemporary art world. So I was learning a lot about how to talk about this kind of humble craft and this approach to making something like a sketchbook. That’s the one thing that remains the same to this day: people walk away from a session completely thrilled that they made something, and you can’t deny that that impact will carry through in their lives on some level. The best thing is, there’s always a person who makes a book, and then tells me they’re gonna give it to somebody — and its like “wow, an act of selflessness in the world!” People spent all this time and effort, they have this really lovely object, but they want to make sure somebody else has it. That’s a beautiful revelation that comes forth in every workshop.

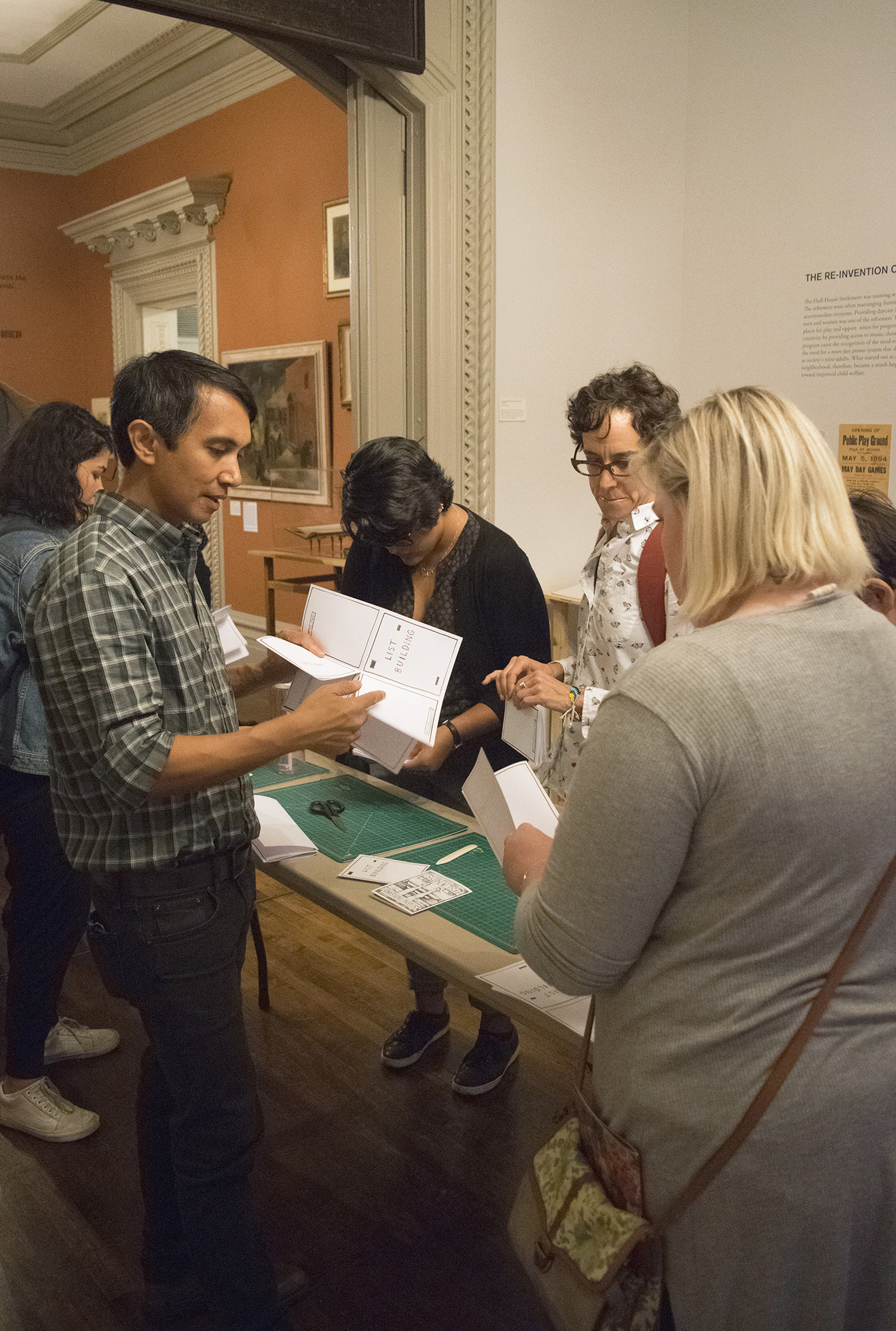

GR: And you did a workshop at Hull-House as well, as part of the Participatory Arts show. Can you walk me through how you structure the workshops, and what you want people to leave with other than having made a book?

RI: Usually I share that story about why I make books. I basically explain it as a three-step process. Making signatures is one step, so you’re making the text block of the pages. And then a second step would be making covers. And the third step would be putting those two together with a particular type of stitch. The majority of the workshops we’re doing, it’s just simple pamphlet stitches: a folio stitched down the middle, or sewn down the middle. One of the things I stress in the workshops is that materials don’t have to cost a lot of money. I’m a big advocate for recycled and repurposed materials, and I highly encourage non-archival material [laughter], which bookbinders would of course probably scream at me for! But you know, regular cardboard, cereal boxes, other things you’d find in the recycling bin. I reuse things that people are probably familiar with on a day-to-day basis. So presenting it in a way where they can go home and think “oh, I can still make a book.”

GR: Talking specifically about what you have right now at Hull-House, and I’m thinking about when you were talking before about when you had shut down the storefront and you were moving into this phase where North Branch was starting to become more project-based and mobile — so did your use of these pedestals and cart forms kinda grow out of that?

RI: When we had the storefront space, we had a very unique bench that was donated to us, and I refurbished it with my dad so it had a very important meaning to me because we had worked on it together. It became this three-seated bench that has these little odd writing tablets connected to it, kinda like a school desk except it was one long bench with three sections. So I decided we were gonna put some books on these and put them outside, because there was a bus stop there right out front. So while people were waiting for the bus, maybe at least they could respond to these questions and interact with this. So it evolved out of that, because we were actually getting some good responses to it. People would come across them and interact with it on some level, and then we would come back and replenish the books or make sure the books were getting switched out. And each book would have a different question. It was great to see the range and the willingness of people to interact, not only to the question, but also to each other.

GR: You’ve also used carts in other projects, right? Is there some kind of common thread about the cart as this mobile form that goes through each of these projects?

RI: Yeah, its everything about mobility, basically. This idea that, through travel you’ll be able to experience something new, and you’ll encounter new people, and you’re gonna put yourself in a place that will prompt more questions, maybe internally, maybe externally. And it’s definitely this idea of mindfulness. I’ve been thinking a lot about that. I’ve always been an advocate for travel because like I said before, I never got to travel. And the pedestal is also maybe a stand-in for where I could be, or someone could be who isn’t physically there. So there’s constantly a space for conversation with other people.

GR: Yeah, I think that’s really interesting in the form, especially thinking about the ones at Hull-House that are very much like a podium, or when they’re right next to each other maybe it’s like a debate, or do they speak to each other in a way, right?

RI: Yes, or there’s the short ones that are more accommodating for people who couldn’t reach the podium for whatever reason. Another one has the elevated wheel base that has the speaker in it, and that’s really intended to be a podium. That was an evolution of the pedestal project because now it’s an actual podium that engages readings and conversation in a different contextual space where people are able to share their thoughts through their own writings or other people’s writings. So this idea that all sorts of things can happen through travel is really exciting to me, and I think in this day and age, where you’re talking about immigration and people moving from one place to another, and the trials and tribulations of what they go through — and what it means to have to move, as opposed to being able to move. It’s all relevant to me, it’s all stuff that I think about, as an immigrant myself, sure, but also as someone who is privileged enough to see it, you know, and to see how other people deal with it. It’s an interesting privilege that artists have to be able to speak on that level, and it’s something I definitely don’t take lightly. But hopefully it’ll allow people to think about what other people go through.

GR: Yeah, and kinda using that privilege that the artist has, pointing it towards an inquiry or these questions that lead into these larger issues. Returning to the questions really quick, I’m curious about how you generate the prompts [for the books].

RI: Each book basically has one question assigned to it, so on the cover it’ll say “who are you?” or “where are you going?” — those were the first few questions that I tried when we had the storefront space. And that was related to trying to talk to people in the neighborhood at the bus stop. I try to avoid questions that are a little too directly about something, so it’s fairly open-ended. I leave it up to the responses that we’ve accumulated from other books.

GR: Once one of those books is filled out, then you swap it out with a fresh one. What happens with the full books, or what is your aspiration for them?

RI: We keep what’s called a “neighborhood archive,” as an archive of these hand-built community collaborations that took place over the years. Some of them did turn into questions and prompts for the pedestals, and others are just sitting there as references or sources or teaching tools for other people. I kinda see it as, like a vault, or photo albums, or, you know, everybody has a place where they store these collected thoughts, collected experiences, collected moments. For me, again, that connection with people through the tangible flipping of pages makes a difference. The neighborhood archive is constantly evolving.

GR: And so the pedestal carts, you put them out in public spaces too. How do you make decisions about where they go, and how do you see them functioning differently in that setting as opposed to in the gallery or whatever?

RI: I think my only criteria was that it’s a high-traffic area. It’s gonna be in a place where people come across it on a regular basis.

GR: Where have you tended to put them?

RI: Its been at libraries, schools, we brought it to some festivals, that’s another high-traffic area. Its temporary but also semi-permanent, like at libraries and schools and such, they fill up pretty quickly. And right now with the ones at Hull-House, it’ll be interesting to see how that goes.

GR: With the show there’s this linking or connecting with some of these archives and histories of the Hull-House itself, to contemporary practices of someone like yourself. So with your pieces, they’re set alongside this context of Ellen Gates Starr and the creation of the Hull-House book bindery. And I wonder if there’s any direct connection to that history for you, or does it resonate in some way?

RI: Her bookbinding, as I’ve come to learn, was very traditional. She wasn’t doing blank books, she was actually binding printed texts — very ornate, leather-bound, using these very meticulous, patterned working tools. And interesting enough, she ran into that same kind of issue about limited capacity to reach [further]. She wanted to continue this, but it became too expensive. The same issues I was dealing with, but in a different context — it affected her work with the community. What I love the most is that a lot of the books, I didn’t even make myself. Other people had their hands in it, and that’s the thing that resonates the most. There was a true community aspect to it: some people may have folded those signatures, other people may have stitched that one particular book, and its remained relatively anonymous — it’s a true collective, a true collaboration. And I don’t know if Ellen Gates Starr envisioned that when she was doing her work, but I would like to think that the kind of work that’s being done at the Hull-House always had those sort of intentions. This idea of community was not specific to how only one person defined it — it kinda evolved, and continues to evolve.

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org

Featured Image: Installation view of the Participatory Arts: Crafting Social Change exhibition at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, showing multiple pedestals from Regin Igloria and North Branch Projects’ series Everything on Wheels, set amongst historical information about Ellen Gates Starr and the Hull-House bookbindery. Photo by Greg Ruffing.

Greg Ruffing is an artist, writer, organizer, and curator working on topics around the production of space at different scales — from the macro level of sociopolitical structures and architecture in the built environment, down to an emphasis on community, collaboration, and exchange on the interpersonal level. He is the Photography Editor at Sixty Inches From Center.