Ryn Osbourne is a visual artist and arts administrator originally from Ohio and based in the Midwest. Osbourne has worked in direct service as an educator and mentor, facilitating arts-based activities with youth of all ages. As co-manager of MINT Collective (2015–present) in Columbus, OH, Osbourne has helped carry out multiple community programs including “Junk Dada Super Sunday” for the Wexner Center for the Arts. She has worked with VISIBLE:INVISIBLE, a program which hosts studio art workshops for homeless youth in Columbus, OH, and AXIOM: A Judgment Call for the Arts helping to organize artists to participate in art making workshops with inmates of Merion Correctional Institution in Ohio and providing project direction aligned with ethical community practice.

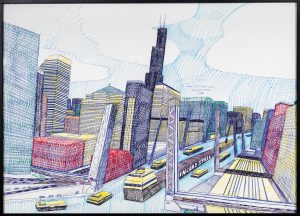

After relocating to Chicago, IL in 2016 to pursue her M.A. in Arts Administration and Policy from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Osbourne has worked with the Hyde Park Art Center as an education and programming intern assisting with community focus group research, has provided administrative support for Gary Lights Open Works, a social practice project based in Gary, IN, and has worked with SAIC at Homan Square in the North Lawndale neighborhood of Chicago administering youth art programming and contributing to SAIC at Homan’s community relationship building efforts.

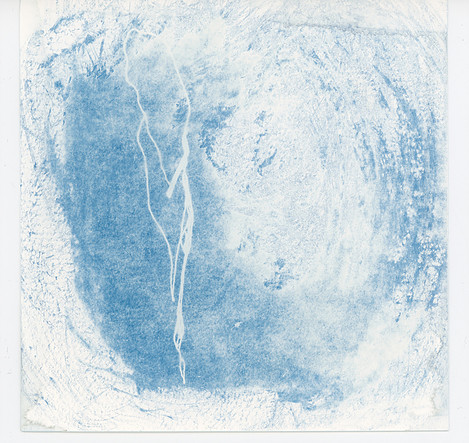

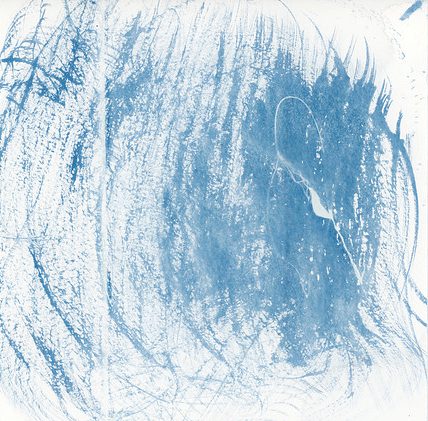

Osbourne’s visual art practice utilizes the process of cyanotype printing both for its experimental, unpredictable nature as a medium and for its phenomenological qualities in relation to arts-based research.

Emily Breidenbach: What are you currently working on?

Ryn Osbourne: After school, my professional goals are to work in development and philanthropic policy. My thesis is on collective impact, the idea of complexity, and problem solving social impact. So, instead of looking at problems and solutions as cause and effect relationships or isolated situations, I’m looking at how in the nonprofit sector arts and culture organizations as well as funders are looking at problems as things that happen in more of an ecosystem, where there’s multiple factors and multiple solutions and the outcome is not necessarily predictable. So, rather than being like, “okay, this is the problem, this is how we’re going to solve it, and this is how we’re going to measure that we solved it,” it’s adapting your mindset to think more like we’re going to learn as we go: this might happen and we can’t predict it. So, my thesis broadly is looking at that way of thinking and if it’s working, if it’s making any “impact.” Who’s doing this work and why are they doing this work? Is it becoming popular? Why is that? I’m looking at this network to see what’s working and what could be useful, but also because it’s a project for myself and my career.

EB: How did you get interested in this?

RO: My background is in direct service and social engagement in terms of programming. I’ve done a lot of workshops with vulnerable populations—I’ve worked with a homeless “tent city” community, homeless youth, people subject to the criminal justice system—and I thought community engagement was going to be my niche. At one of my previous jobs, I realized that my work as an administrator was very much influenced by the expectations of our funder, which is not uncommon but it was different for me to experience that firsthand and it made me think, “well, this is affecting the way I do my work and, more importantly, this is affecting the way I can build relationships with people,” and it caused me to rethink my career goals and to think more about where or how programming decisions are made.

EB: How did this affect the way you built relationships with people?

RO: My goals in that job were more about recruitment than maintaining genuine relationships. So, if I were to go to a community event for instance, I would be at a table with marketing materials—even the physical table felt like a strange barrier. I was at a food drive and everyone was participating, picking out what they wanted, talking with each other. There was a real community feeling and I was over here with my table kind of like I was observing it and it felt out of place or disingenuous…especially because I strongly believe that shared work is how you build community, so shared work would be shared volunteering. If I was there volunteering, I could have been sharing the work and meeting people and building community that way, but because there was so much pressure to make sure the marketing part got done, the priority was to be at this table representing my institution instead. It makes me question what gets funded and why, and what are the distribution models for this work. I wondered, if I need to get to the bottom of this, where do I need to go? That’s how I arrived at my current thesis work but, in doing so, I realized it’s a much bigger question. It’s a whole system that needs to be looked at.

EB: So what are you looking at now to get started on this project?

RO: Right now, I’m looking at the mission statements of different foundations. A great example is the Field Foundation and how they’ve changed their funding priorities to support programs happening in specific geographic areas based on racial demographics. I had a really cool experience. I’m currently a development intern at Gallery 400 and I went through the process of submitting an LOI to the Field, and it was interesting to read through and respond to their funding initiatives. The whole time I was wondering how they decided on the questions they asked and the language they used. Their website has a lot of great resources that support the work they are doing. The changes they are making are an important move towards equity. I’m interested in knowing how changes in their funding priorities happened. Who did it, how did they do it, and how did Angelique Power become president in order to make those decisions?Where does the Field fit into this whole funding ecosystem? If the Field’s doing it, are other people going to do it now? Those are the types of questions I’m looking at.

EB: What type of form will this project take? Will it be a written piece?

RO: I met with Kate Dumbleton (Assistant Professor of Arts Administration and Policy at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Executive Director of the Hyde Park Jazz Festival), one, because I wasn’t sure how to explain this type of systems-thinking without making it too complicated, and I also wasn’t sure what the end product was going to be. Kate actually suggested I explore doing a visual project out of this, which is awesome because I’m also an artist and some of my work has been arts-based research projects. So now I’m feeling extremely energized, motivated, and ready to go!

EB: Speaking of your arts practice, when did you first start creating art?

RO: Oh, yeah. That’s a complicated question. I started doing art because I majored in sociology in undergrad and I felt like writing a paper wasn’t useful for the things I was trying to communicate. A lot of my undergrad research was dealing with place-based symbolism, so I was thinking about what visual indicators are there in your neighborhood that make you feel like you belong there. For example, I was going through my neighborhood and I saw X and that makes me feel this way and it’s home. So to do that research I did a lot of photography. I got into the arts through research in that way.

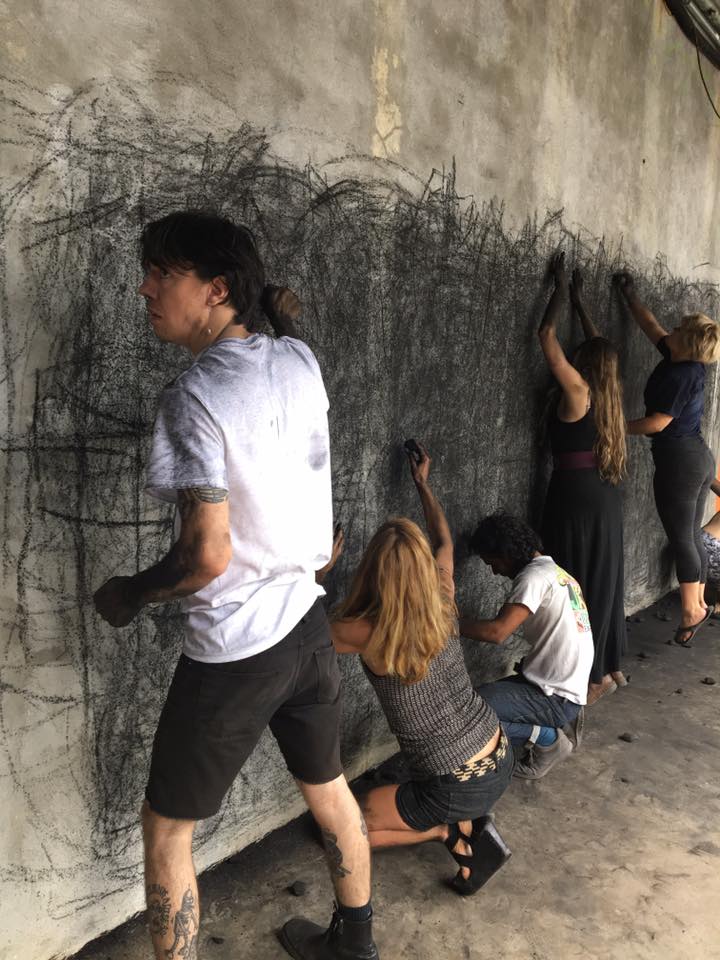

EB: Can you speak about the residency you did at PORT Gallery in New Orleans?

RO: This was a residency I did in New Orleans last November for three days organized by Pamela Bishop, Valentina Vella, and Heather Hanson. It was three days of art and intensive art making. The residency was called Dark Matter and that was the general theme. Artist Heather Hanson, who facilitated the residency, does really beautiful kinetic drawings and has a background in Butoh dance. A lot of what we did during the residency was exploring ideas of self and self-understanding through workshops of acting-out things. For example, we did a workshop where Hanson said, “Okay, here’s the space, act out your life from birth to death.”

EB: Wow, that’s intense. So what did you do?

RO: Well, I was born. I thought about my mom a lot. There was a moment I remember, walking across the entire gallery with swan arms—just like, “get out of my way!”—because I did have that moment in life. By the end of the life cycle workshop, I laid down on the floor and I let myself die alone, which was really important for me because I was having a lot of difficulties through my art—my art that’s not based on research—in confronting what it means to have a perception of self and how it changes. For me to feel grounded and successful and able to do my work, having a solid home, and sense of who I am is very important.

This artwork I do that’s not research based, a lot of intuitive drawing and cyanotype printing, is very much an act of self-reflection, which does relate to my administrative practice because it grounds me. Without that work and without that space to work through and express those things about myself, there’s no way I would be able to maintain this professional performance or public self. I still consider my art making a practice because if I had more time, I would be taking it even more seriously. It’s not a hobby, it’s something I need.

EB: So, you’re talking about your artwork in two main areas: research-based photography and artwork that’s not research-based. Can you explain a little bit further? Does research-based artwork mean community engagement to you? Is it not that?

RO: My first research-based artwork—or if you want, you can use the term “social practice,” though I’m not sure how I feel about that term—was a participatory photography project with a group of homeless people in Wooster, Ohio, where I went to undergrad. I went down to this homeless community, which was a very contested space. There were a lot of people in Wooster trying to get these people removed from the area but the leader was claiming Native American tribal rights to the space. There was a lot going on, a lot of different narratives. I did a project where I gave the homeless folks disposable cameras and asked them to document their perspectives, and then I had the images developed and gave the physical pictures back to them. But even just asking those questions, I became friendly with them and would go visit them and ask, “Oh hey, how are you doing?” That’s research in the sense that I learned information and was able to have a dialogue. The material I had included images and quotes I would write down while talking with folks. The images and some of the quotes were exhibited at City Center Gallery in Columbus, OH in 2015. I organized a campus-wide goods donation and I was able to tell my peers what I learned about the “tent city” community when picking up their donations and explaining the project. I’m still thinking about how I could get this material out into the world in a way that would be the most useful. The camp was recently disbanded. The strangest part of that project is that I did it before I knew that “social practice” was a thing.

EB: You just had an instinct that this was something you wanted to work on.

RO: Yeah, the problem was that these people’s stories weren’t being communicated and they were negatively stereotyped in the press. It’s interesting, it wasn’t like I set out to do a social practice project.

EB: Right, it wasn’t like you said, “I want to work in the genre.”

RO: Exactly, it just seemed like the best way to answer the question.

EB: Did you know that social practice was a thing when you started working in this way? Did you know there was this network out there and that funding existed for it?

RO: Not at all, this was in 2013.

EB: What did you think when you heard about other people working in this way?

RO: At first I was really excited but I’m also still trying to fully understand it. I heard someone refer to another social practice artist as a superstar. They said, “So and so’s a superstar, they’re blowing up right now,” and that caused me to think more critically about social practice. There’s a lot of harm that can come to communities if you’re an artist and you’re doing a project for your own ego. There’s a lot of funding in this area. I talked to another artist who has done a lot of social practice work and she was honest and said, “That’s where the funding was so I adjusted my practice to incorporate social practice.” Her work is great, and she’s awesome, but I don’t know how I feel about that.

EB: This related back to what we were talking about earlier. The funding priorities not only dictate the way you were navigating that particular institution, but in this case what the artist is working on.

RO: I think the mentality of thinking of communities as people who need something is a problem. Everyone has something they can offer—whether it’s time, ideas, opinions, a house—everyone has something they can offer the world. I’m more interested in leveraging what everyone has to offer instead of creating a solution to a problem and filling a need, or at least co-creating the solution within the community rather than bringing something in.

I’m definitely learning this more as I keep researching. And when I think about the people and communities I’ve worked with, they don’t ask for things, they’re not needy, they’re super appreciative of what they have access to in the arts. This mentality of coming in and being open to community needs and feedback has become a sign of success. When an organization wants to do a community project, the first question is always if they hosted that meeting. Did they host that meeting where they asked the community what they needed? But even if you host that meeting, what questions are you asking? What are you taking away from it? Whose voices at that meeting are the most present? It comes down to thinking about what your relationship as an administrator is to your constituents and why. There’s a really beautiful quote in Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldúa that makes me think critically about my intentions when doing community work.* If you think of the community as something you serve, you might other them, even if you’re trying to help. So, to get to that impact that you really want, I feel like you need to be in it all together.

So I’m over here trying to sew that all together. This also goes back to place-keeping as opposed to creative place-making, where you’re preserving what’s already there instead of coming in to make something new. Why do we need to make something new? What’s wrong with what’s already there? Anyways, I feel like I have this soup of thoughts and I’m trying to figure it all out.

EB: Thinking about past projects or future endeavors, what qualities or values in institutions and organizations do you prioritize when approaching new work or a new position?

RO: Transparency is very important to me. Even being transparent about your values is really important. Everyone knows I love the Hyde Park Art Center because I feel like the people that work there embody the values of the organization. I see it in the way that they treat each other and in everyone who walks through the door. That’s important to me. I also seek out challenges. I’m thinking back to my first year of graduate school and thinking about how I chose the projects I worked on.

EB: Right, so what attracted you to working on the Gary Lights Open Work project?

RO: Gary Lights Open Work is a social practice project and I was convinced that that’s what my career was going to be. So, a lot of that decision was that I thought it’d be good experience to have or that I could bring a lot to the project. But now I’m obviously thinking differently about it. Moving forward, I would prioritize trying to work on something that offers up alternative models or that tries to do things differently.

A lot of what I’ve been doing this semester is reading the mission statement of many arts organizations and foundations that do community-based works. Sometimes I feel that these places just copy and paste their mission statements from each other—it’s generic, it’s like, “Now we are engaging the community, this is impactful civic practice.” Buzzwords. And that’s not surprising. For me, the question is still, “But what are you specifically really doing that’s unique to you? Why did you decide to do it? Not to be a skeptic, but what is your story? Where did this project originate, where did it come from? Who asked for it?” I think that’s really important.

I heard Amanda Williams talk at the Museum of Contemporary Art this week and I think her work is amazing because she grew up in Englewood. She grew up where she’s working and you can’t replace that experience. Even if you’re a social practice artist who moves to a neighborhood and lives there for a long time and makes an effort to integrate themselves, I don’t think you can ever replace a willful knowledge of home and the feeling that a place is your neighborhood. I saw her project and I thought it was awesome. It’s not complicated, it’s really beautiful, and she’s making art out of what she knows. I think the story behind the work is really interesting and important.

EB: What is a challenge you personally face as an emerging arts administrator?

RO: My background in arts administration has been in arts education and community practice projects. It’s less of a focus on the hard administration skills and more emphasis on mentoring, relationship building, empathy, and people management. I grew up in a small town in Ohio and empathy was something I was raised on. Not even because I’m from Ohio, my mom is the most empathetic person I know. So, it’s challenging to be in a field where empathy is part of your job but it’s also part of who you are. While working for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago at Homan Square in North Lawndale, I had to learn very quickly how to draw boundaries with people because I realized I showed up to work everyday as myself, I didn’t show up as an administrator. I showed up as Ryn. It’s difficult to figure out boundaries around how much emotional labor you can give to your job. It’s hard, learning how to be an administrator and learning the difference between a job and who you are. Because for me, administration is such a people-focused career.

One of the reasons I was interested in studying in Chicago was because I knew there’s a history here of social practice and community organizing. There was a moment after being here where I had to differentiate my work from the world that is “social practice” in Chicago in some ways. I needed to carve myself out instead of going with the method of work that can be a social practice project. I had to think about who I am, what my work is, and what I value within this big city and history of social practice. That became very apparent to me in the series of books that Mary Jane Jacob and Kate Zeller edited, called the “Chicago Social Practice History” series.

It’s interesting to me to read through and start to recognize names and realize how tight the social practice community seems to be in Chicago. Mary Jane Jacob put them into a book; it’s a nice anthology. I learned a lot from reading it, but it made me think really critically about how my work fits within Chicago social practice, especially knowing that this way of thinking and this community is here and available.

EB: You’re from Columbus, Ohio and are part of the MINT Collective there. How involved are you with that still? Is most of your attention here in Chicago now?

RO: MINT is in transition right now because we recently moved out of our building. We had been renting a huge warehouse where the front half was used for gallery space and performances and the back was used for studio space. We’re not a 501c3. The City of Columbus gives grants towards creative place-making—anything focused on arts economies, vibrancy, revitalization, that whole narrative. It was interesting being an artist in Columbus and knowing that my art wasn’t in the vein of the city’s funding priority, at least in my opinion and the opinion of my friends.

Since MINT moved out of the building, they’ve organized some off-site exhibitions. One was at Frieze New York and the other one was at another artist-run space in Columbus called Skylab. That installation was called Will Play for Space. I was in Chicago, so I wasn’t part of the conceptualization of it, but the collective put together an installation of a basketball court. The idea was that in Columbus, you’re playing for your space. Not just physical space but being visual as an artist and being recognized by your city. I participated by writing a large portion of a statement related to the show. It was about what it means as an artist to fight for space in your city, especially after just losing our building. For me, that really related back to some of my research about creative place-making.

MINT was an awesome first experience as an administrator because it really was genuine. It wasn’t like I had to learn my role within an already existing organization, but more about what skills I had and how I could contribute to MINT. This was a great experience in doing something without worrying about the expectations of funders. We never had major funding, we did crowdfunding. It was a great experience in learning about a new audience, working with artists, managing everyone’s expectations, and learning how important it is for emerging artists—visual, performance, and musicians—to have a space to show their work and form a community. My role in the collective came to thinking through what everyone wants. We didn’t have a board, we didn’t have a hierarchical decision-making process. We did it collectively. It was interesting to see how self-organization works. If people wanted to do something, they just did it. They figured out how to make it possible and did it. Through MINT, I was also able to do work in the community because people in Columbus would reach out to us as a collective and certain members could choose to respond. We did a few workshops with homeless youth with another organization called VISIBLE:INVISIBLE, we did an installation and a workshop with the Wexner Center for the Arts to go along with their exhibit at the time: “Junk Dada: Super Sunday,” and we did an art workshop with the elementary school I was working for at the time. As opportunities came up we took them.

EB: It sounds like that experience could be related to what we first talked about, your thesis research. No one was dictating your priorities because there was such minimal funding.

RO: Right.

EB: Whose work or what projects are you super interested in right now?

RO: There’s an artist named Dana Bishop-Root working in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Braddock is a post industrial city, built originally for the steel industry. The project is operating out of the Braddock Carnegie Library. I think it’s a great project for a couple different reasons. One, Dana moved there and lived there for two years before she initiated this type of programming. She went and talked to people about what they wanted in terms of art programming and also had a lot of discussions around race. She’s a white artist working with a primarily black audience. Now she runs a ceramics and printmaking studio in the library, which I think is great because the library is already a recognized cultural space in the community. They have a puppet collection, not small puppets but the type of puppets that you wear like a costume. They have a whole collection of them and do a parade. Her project is low-scale, it’s specific to her neighborhood, and it felt very genuine when I visited the space.

* “In trying to become ‘objective,’ Western culture made ‘objects’ of things and people when it distanced itself from them, thereby losing ‘touch’ with them. This dichotomy is the root of all violence.” From Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, by Gloria Anzaldúa.

Featured image: Photo of Ryn Osbourne by Juan Carlos Herrera.

Emily Breidenbach is an arts administrator with experience working at museums, education centers, and non-profits. She is currently the Assistant Director of Marketing and Enrollment for Continuing Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and has previously managed strategic communications for the Krannert Art Museum, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, and the Museum Education department at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Emily Breidenbach is an arts administrator with experience working at museums, education centers, and non-profits. She is currently the Assistant Director of Marketing and Enrollment for Continuing Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and has previously managed strategic communications for the Krannert Art Museum, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, and the Museum Education department at the Art Institute of Chicago.

She has a B.F.A. in Art History from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is currently pursuing a M.A. in Arts Administration and Policy at SAIC.