You’ll be hard-pressed to find a lover of libraries, archives, and printed matter more devoted than Marc Fischer. He’s known for a long practice of discovering, creating, and distributing books and ephemera, making him a regular at libraries and post offices throughout the city. It’s practices like Fischer’s, which pays close attention to how, why, and what libraries, museums and archives collect, that have served as inspiration for the work that we at Sixty do, as well as our focus and approach. In 2007, he founded Public Collectors, a project that uses publishing and exhibitions to give glimpses into people’s personal collections–ones that usually go unseen. Prior to that, he and Brett Bloom founded Temporary Services, a project started in 1998 which also holds under its umbrella Half Letter Press, whose publications I’ve come across in Los Angeles, New York, London, and many bookstores in between.

But his commitment to printed matter in a time of digital dominance isn’t exactly what makes these projects get the notice that they have over the years. It’s the strength of the content and Fischer’s ability to shine a light on things we often don’t pay much attention to, never knew existed, or often take for granted.

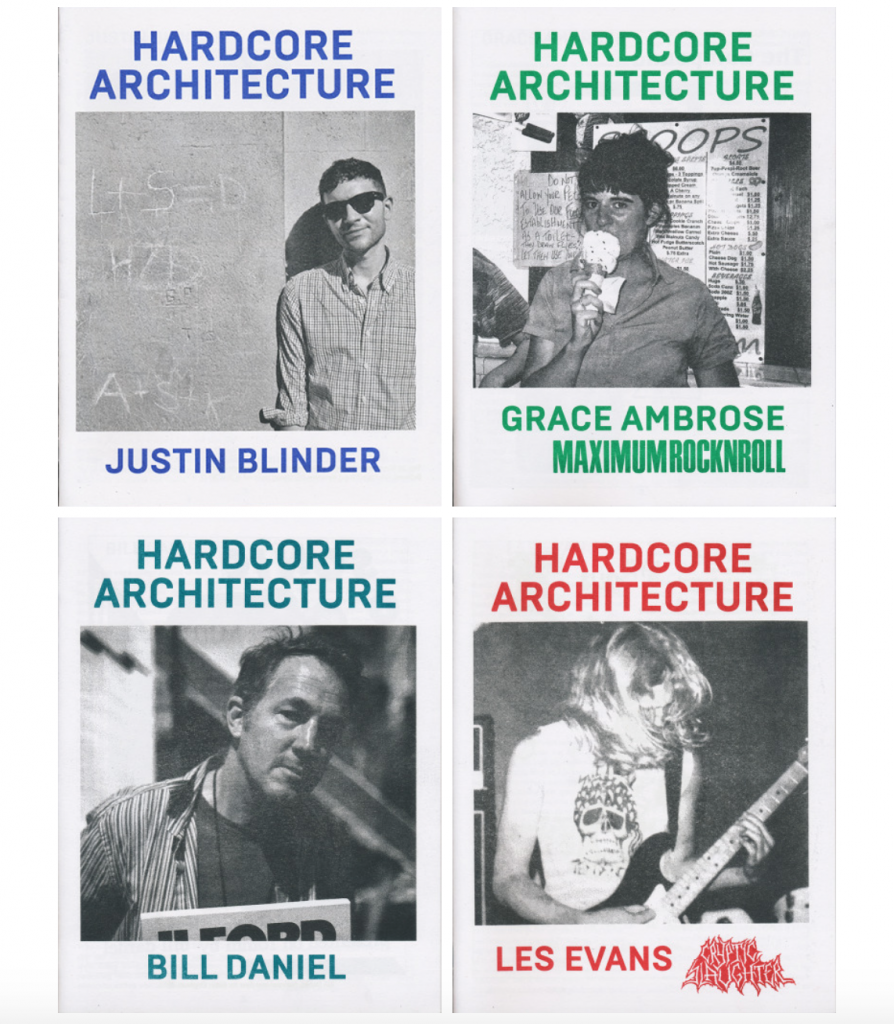

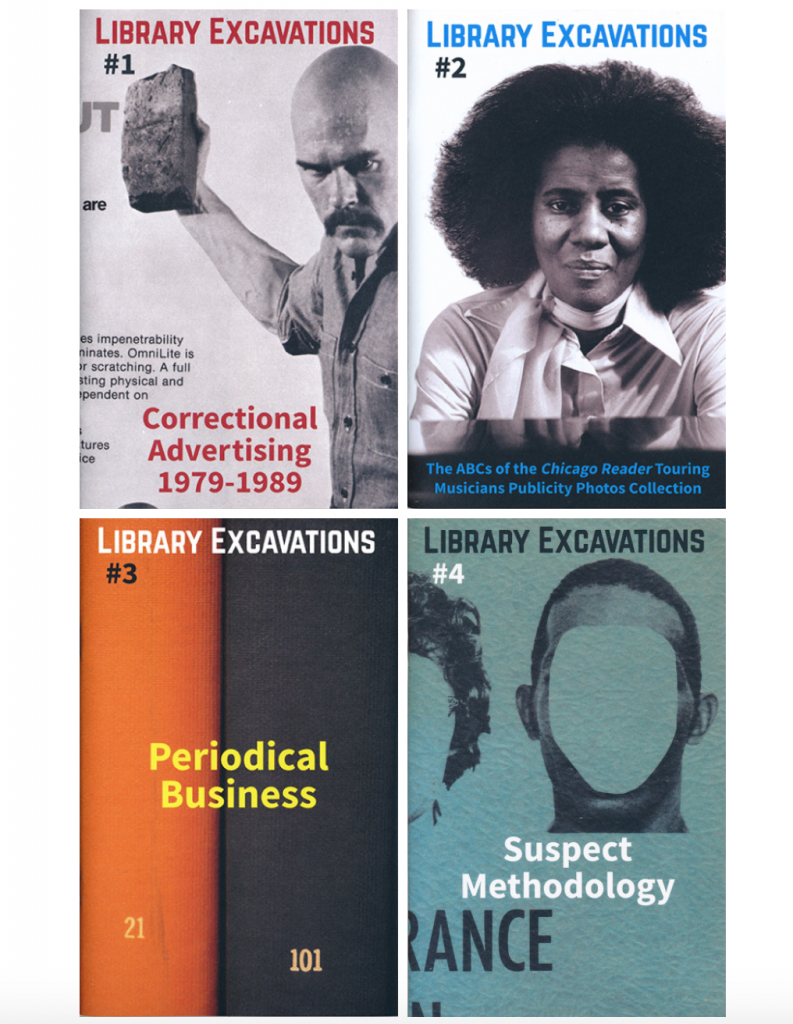

This is certainly the case with Public Collectors’ latest publications, Library Excavations, which is an ongoing series of booklets created from content found on the shelves, in the stacks, or in the archives of the Chicago Public Libraries. The first four forefront topics that lie just below the surface of things that confront and concern us everyday–incarceration, the music industry, racial biases and profiling–but presented in a way that minimizes a heavy-handed or swayed contextualization, allowing for the content to speak, pretty loudly, for itself. Even with these four publications that alone have so much to say, Fischer took some time to explain his process for selecting the content of each book and why he finds such value in libraries and repositories.

Tempestt Hazel: I’m going to start with a quote that I think is really important to call out–especially for those who might not be familiar with what you do: “Public Collectors prefers direct experiences of physical media over the digital.” Can you talk about where that leaning stems from? Since Public Collectors is only about a decade old (started in 2007?), I suspect it might come from a personal relationship that you have had with printed matter for a long while. Is that the case?

Marc Fischer: I’ve been publishing since I was a teenager, starting in about 1987. I’m 46, so I’ve spent almost two-thirds of my life making and lugging around printed matter. From my high school and college ‘zine-publishing days, to my current book and booklet-publishing days, I’ve always connected with other writers, publishers, and artists that publish. Additionally, I collect this stuff. It chases me down. I save all kinds of posters, flyers, books, booklets, tracts, magazines, journals and whatever else. It’s inspiration for the things I make and research material. Pieces of paper illuminate a million moments from my life.

A lot of information about an object gets flattened when you can only understand it in digital form. If you buy a magazine from 1970, you are holding the same thing that someone else held when they bought it 46 years ago. You are holding all of the decisions and processes that went into the production of that thing. If you buy a Library Excavations booklet, you are holding something with a cover that was printed by a commercial printer, interior pages that I printed in my basement on a RISOGRAPH duplicator owned by the group I’m part of, Temporary Services, and that was then collated, stapled, scored, folded, and trimmed by Union Book Bindery on 16th and Western in Chicago. A PDF of a booklet reduces those textures and processes to a bunch of pixels on a screen.

Don’t get me wrong; being able to experience something in an inferior way is better than nothing. The Harold Washington Library Center has a collection of over 400 reels of Microfilm collecting underground newspapers from around the world from the 1960s until the 1980s. It includes thousands of extremely hard to find newspapers. It’s an outstanding resource, but it’s also very hard to look at anything on Microfilm for long before your eyes get fried. Still, at least there’s a way to see this stuff. Tons of it is not on the internet. I’ll take what I can get, but if I want to experience the full weight and meaning of a thing, I want to experience the physical object. That’s how I prefer to engage with history and with ideas. It’s so much more pleasurable and memorable than always being dependent on a computer for everything.

TH: Libraries could be considered, for some, overlooked and underutilized gems. What is it about libraries that keep you working in and advocating for them?

MF: I visit libraries for reasons that might be similar to why some people go to museums: to be inspired, to be surprised, to see something I haven’t seen before, to visit favorite sections of the building or collection, and to hopefully find something that I was unaware of that might expand my understanding of the world or human creativity.

Libraries are a lot more democratic than museums, however. They are free, they attract a more diverse range of people, and like democracy, they can be a bit messy–particularly as these buildings become a refuge for teenagers that lack other safe spaces in their neighborhoods after school, or people living on the streets or otherwise existing on the margins and looking for access to basic services like bathrooms, water, and electricity. Libraries are also on the frontlines of protecting free speech, and while library holdings could always be more diverse and radical, a good library like the Harold Washington Library Center contains a broad range of published perspectives.

My original hope with Public Collectors was to persuade private individuals, starting with myself, to inventory their collections and make them available publicly to people that want to come over and see them, and for individual collectors and archivists to avail themselves of their knowledge. That mostly hasn’t been very successful. People feel weird opening their home to strangers; people feel weird asking strangers to come over and see their stuff. I’ve gradually shifted to doing more things like exhibits or events, or creating research projects that make sense as digital collections, like Hardcore Architecture on Tumblr.

Part of why I want to encourage people to visit public libraries is because they are already these amazing public repositories of hard to see things—particularly libraries with Special Collections—and they are set up to accommodate visitors. What they don’t often provide is someone who has expertise in the particular histories of the objects that they are retrieving for you. People that collect things usually know something about the things they collect, or they have some personal experience that resulted in them having that stuff. I have many publications by artists because I’m friends with those artists. That’s not necessarily the case in a library, but at least libraries have these great things, and the social interactions with librarians can be very friendly and supportive.

TH: What is it that people are missing out on by not using them more–particularly the Harold Washington Library?

MF: We pay for libraries with our tax dollars. We have built these works of architecture for books and information and we should make more of a point to use them.

I have plenty of books and papers and publications at home. I could stay home for years and have enough to look at and revisit, but libraries create all kinds of chance encounters and surprises. Even when a library has a book that I already own, the books next to it on the shelf will be different, and that might be a catalyst for some entirely new exploration.

It is unbelievable how much material many libraries have that no one is looking at. I constantly discover things I did not know existed by browsing in libraries or asking to see something in reference that I have never heard of. The world of books and magazines and printed ephemera is endless and there’s always something new to see.

Harold Washington Library has a lot of skinny booklets that have been re-bound by the library in these generic covers so you really have to narrow your focus and go digging on the shelves to even notice some of this stuff. The other day I was reading some Rand Report from the 1980s about kidnapping threats for international businessmen by terrorist groups, and it detailed all sorts of awful things that have happened to poor Exxon employees, or whatever, at the hands of militant groups in Central America. What a fascinating subject for a little publication! You never know what you’ll find in the library. Book stores can’t compete with the range of any halfway decent library.

TH: Public Collectors has produced an impressive collection of publications over the years, with one of the most recent being the Library Excavations series. How did this series get started? Did you go into the library knowing the specific paper and print resources you wanted to create publications from?

MF: I proposed a similar project and publication series for a residency at a university in another city. When I wasn’t awarded the residency, I decided that I could just work on the same idea in Chicago using Harold Washington Library, which might be a much better way to approach these issues since I live here and because the library is open to the public and there aren’t any of the hurdles to gaining access that one sometimes finds in university libraries. I was able to get a little funding from Columbia College’s Part-Time Faculty Development Grant and that paid for the production of the first three booklets.

There are projects where the thing that I present is the summation of a period of work and the project is more or less complete. Then there are projects where I figure out what the thing is, in stages, and don’t really know what it is until I’ve been working on it for quite a while. Library Excavations is definitely a case of the second way of working. It is great to be able to reflect on this project after only four publications, but I suspect the overall shape of Library Excavations and the issues it calls up could be quite different a year or two from now. I see this as a long-term, episodic project, and some future publications will be curated or edited by other people.

I went to the library with no pre-conceived ideas about what I would make. I could not have anticipated any of the subjects I decided on before I started spending time in the library, and looking over the Chicago Public Library website for Special Collections holdings. I had no idea that Harold Washington Library had the Chicago Reader’s collection of music publicity photos before I found it on their website. I had never seen the magazine Corrections Today before I found it in their open stacks.

TH: How did you come across each collection? Where in the library are they located?

MF: With the exception of the Chicago Reader Touring Musician Publicity Photos Collection, which is on the 8th floor in Visual and Performing Art Special Collections, everything else is in the open stacks and doesn’t need to be requested from a librarian. Corrections Today, the magazine I drew on for the first issue of Library Excavations, is housed with Social Science-related periodicals. Everything in Periodical Business came from the Business Periodicals collection. The publication that was used for Library Excavations #4: Suspect Methodology was found in a reference section devoted to books on policing, law enforcement, crime, and things like that. I’m trying to tap a number of collections within the library and will eventually start making these booklets using collections at other libraries.

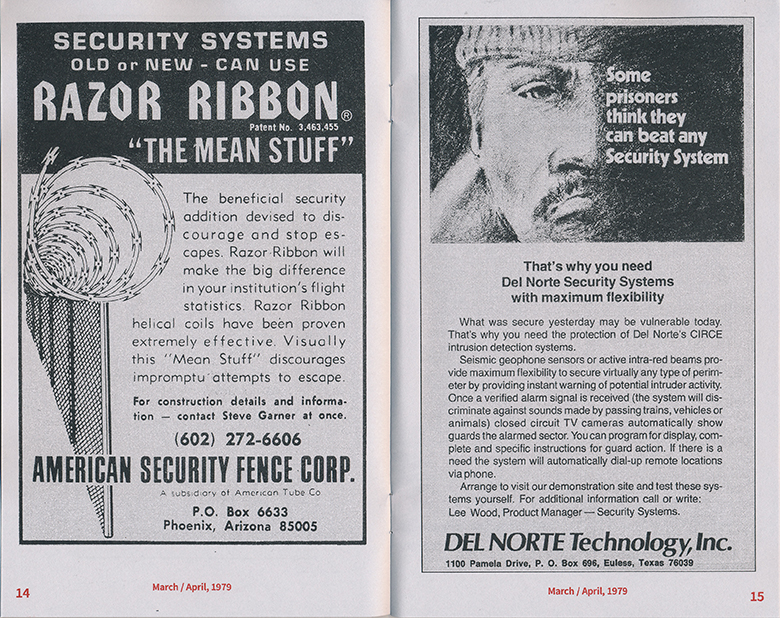

TH: I spent a while reading every word and studying the images in Correctional Advertising 1979-1989, the first in the Library Excavations series. Maybe it was because I wanted to know where these companies were based. Or, it could have been the unsettling feeling that comes with looking back at advertising from right around the time when there was an incredible upswing in the prison population of the US, a history that has recently been agitated even more than usual with films like 13th. Whatever it is, seeing how these businesses appeal to the prison market is really strange. You articulate some of these things in your description of this issue, but could you speak about your response to these ads as you looked through them?

MF: I’ve always felt that it’s valuable to read magazines and publications produced from inside a particular culture, rather than just reading reports about that culture that are not produced by active participants, but rather, by spectators or journalists or other kinds of observers.

My booklet Correctional Advertising only scratches the surface of the business end of prisons, but some themes emerge. Corrections Today, the source of the advertising illustrations in that booklet, is the member magazine of the American Correctional Association. It is still being published. The ads reveal a whole range of issues and problems that wardens and staff must contend with. Some of these realities are not just about prisoners, but also issues involving staff–such as drug testing and other ways of monitoring workers. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of ads about cost-cutting, security, furniture that is indestructible, and various products designed to resist tampering. The visual representation of prisoners and the jokes about incarceration in a lot of the ads are angering. There are absurd caricatures of prisoners and I started wondering who all of these actors and models are that get to play prisoners in ads for the corrections industry.

One of the more weird features in many issues Corrections Today is a multi-page section devoted to annual corrections conferences, which are often held at some kind of resort hotel in a place like Miami Beach or Las Vegas, and these features make a big point to get into all of the amenities. I did not include this in the booklet, but as with all of the publications I’ve made so far, each only begins to uncover a larger phenomena. These conferences seem like they are really big, and they always include notes about the various bands and performers like Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons that will provide entertainment. Or you get these plugs for things like a family visit to the Seaquarium that you can do with your kids in between learning about the transmission of HIV in prison, or how to manage overcrowding.

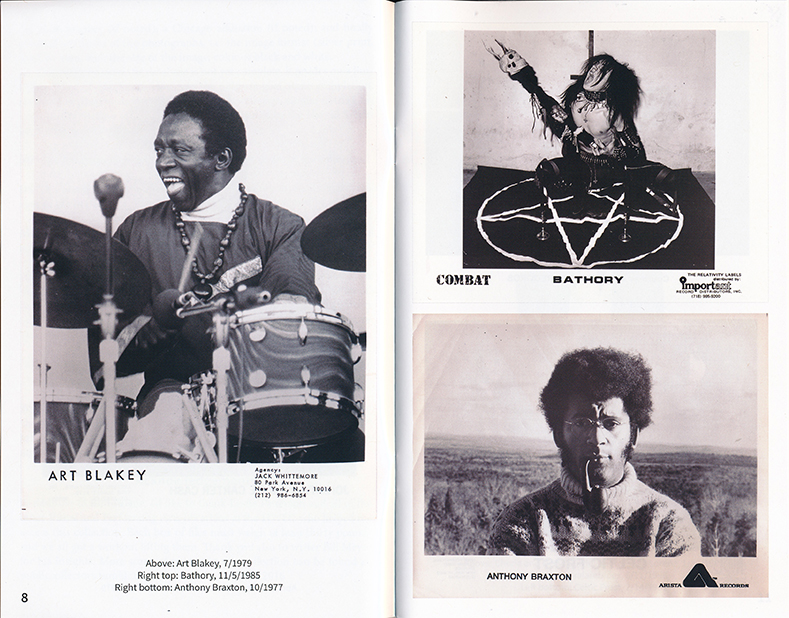

TH: The second Library Excavations, The ABCs of the Chicago Reader Touring Musicians Publicity Photos Collection, seems like it’s just getting started, since you’ve compiled images only from the A, B + C sections. Will it continue?

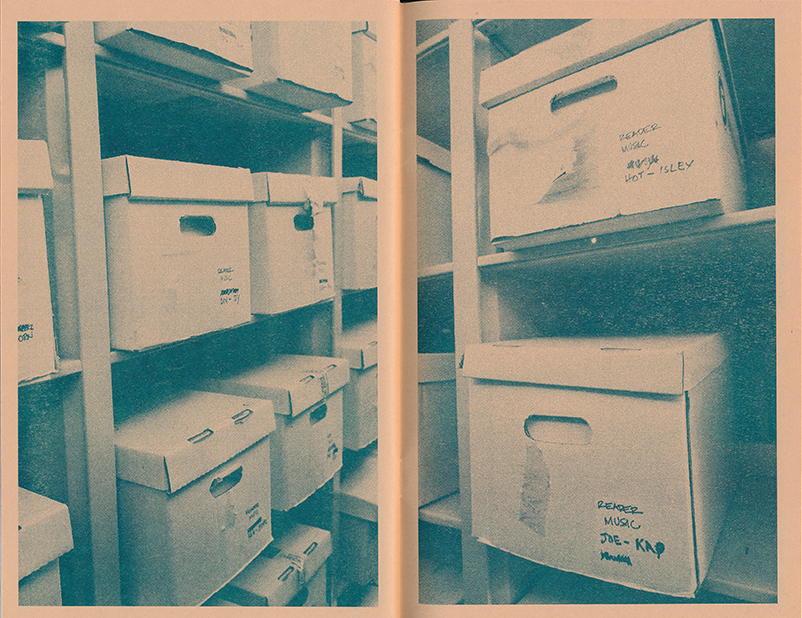

MF: For those who don’t know the back story, all of the Chicago Reader’s touring musician publicity photos are in Special Collections at Harold Washington Library, except for some photos of Chicago musicians (those went to the Newberry Library, which is primarily where the Reader’s archives are housed). The music photos are an enormous collection, spanning from around 1971, when the Reader was founded, until 2005. The librarian Bob Sloane who is cataloging the collection estimates that there might be as many as 70,000 photos.

Each file box weighs about 35 pounds, the poor librarians have to pull them down off of the shelves, and there are over fifty of them. I probably looked at less than 1/5th of the collection over the course of numerous visits. It took about ten hours just skim the surface of that material and scan selected photos.

I made over a hundred scans and have posted some of the extra material on the Public Collectors Tumblr site. My interest with a publication like this is not to chip away at the whole collection, as much as I’d love to see and present more of it, but to consider its existence on a manageable scale, and alert more people to the fact that it is there waiting for them. According to Bob Sloane, I was perhaps the first person to ask to see those photos, even though the collection is clearly listed on the library’s website. It’s a fascinating collection on a number of levels: as a record of incoming material at a weekly culture newspaper, as a survey of music across all genres, as a sweeping study of a particular kind of photography, and as a memorial to the practice of printed black and white promo photos for bands. Those are barely used for music at this point. Almost everything is digital now, downloaded rather than printed and mailed, and much of it is in color.

TH: To go back to your preference of physical media over digital, I think the second Library Excavations issue provides an opportunity to think about the significance of printed matter, like tour photographs, that were once so essential in the music industry and how the internet has completely transformed those common practices. (I’ve had a million conversations about how I miss liner notes and cassette and CD sleeves.) Music is a big love of yours. What’s your take on that shift? Now that there isn’t that space for those details, where does it go?

MF: People who love music will hear it and enjoy it in whatever format they can find, but the physical and social space of books and records creates all kinds of experiences that I just don’t have when I sit at home and listen to an MP3 someone uploaded to Youtube. It’s hard to imagine how many parts of cities I have visited mainly because I was in search of a book or record store. Sources of books and records are a big defining factor in how I explore cities.

I trust that records will continue to exist because they have proven durable since Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877. I can’t easily review something on a floppy disc from 1989, much less a zip disk from 1999, because the technology to use these on newer computers has changed too quickly. My records from the 1960s sound great. They are easy to care for and a decent turntable can easily last for 25 years or more with minimal maintenance.

I love all of the collaborative web-based platforms where users pool their knowledge to add vast amounts of information that you can find in one place. For music, discogs.com is extraordinary. There are, however, so many websites and web-based platforms for music and other information that already no longer exist. Earlier this week I went looking for a website that lovingly documented over 100 mostly self-published books by an artist that I’m interested in, and the site is gone. I have no idea why. A ton of work and scholarship that everyone could see is lost.

Fortunately, however, the books that were documented on that site still exist as physical objects. Take away the making of those books, and you are putting a lot of faith in the internet alone to retain that information. What happens when the person that made the website dies, without having done something to make sure that it stays online?

It’s expensive to turn something into a book or record, and not everything gets to enjoy that luxury. I favor having a balanced approach to creating things that ensures that at least some of what people create will stick around in the physical world for as long as people exist to look at and think about it. As someone who loves music, I’m really happy that platforms like Soundcloud and Bandcamp exist, but I hope everyone is backing up that stuff and circulating hard copies.

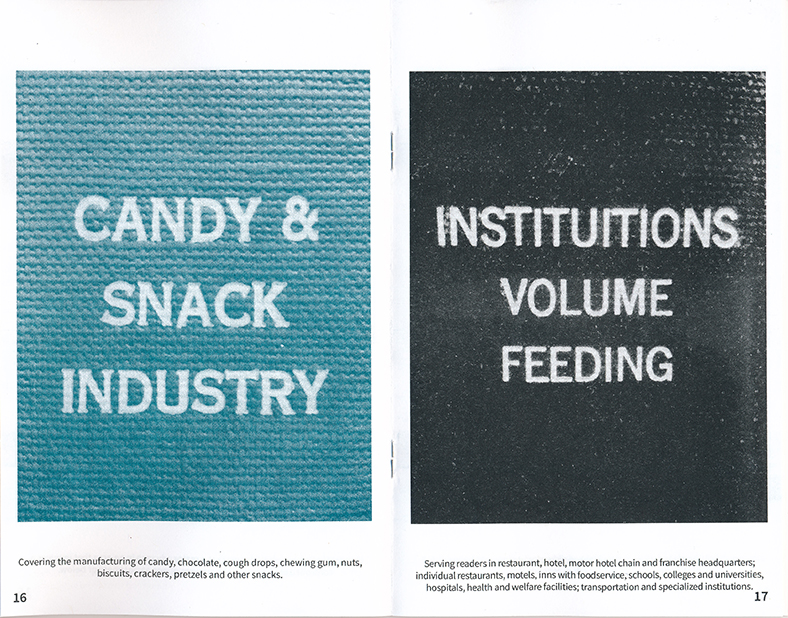

TH: Whether intentional or not, I found a lot of humor in Periodical Business, the third in the series. It was almost like a game where I found myself guessing what the periodical was actually about, especially when the name left it open–like Rubber World, Playthings, or Automatic Merchandiser. How did you choose which titles to include?

MF: I had a lot of fun with that booklet and I’m glad the humor comes through. That booklet came about in a very intuitive way and I tried not to obsess over my choices too much.

I decided to limit myself to periodicals I could readily see. Harold Washington Library has probably thousands of magazines that are not in the open stacks and must be requested from reference desks. Most of the Visual and Performing Arts periodicals would have had to be requested, for example. I stuck to the business periodicals. There are hundreds of sociological journals and other periodicals in other parts of the library, but I try to give myself some basic parameters so that I don’t get overwhelmed.

My initial impulse was to just photograph the names of the periodicals as they are stamped at the binderies. I liked the way the generic stamping on the spines created a kind of equivalent feel to the subjects, no matter how different they are in content. It was toward the end of the booklet’s conception and design that I decided to add little captions that described the periodicals in the publishers’ own words, whenever possible.

I’m always trying to consider the line between the poetic or playful aspects of my selections and juxtapositions, and the informational aspects of the source material. I like the way the title Rudder looks next to Vacuum magazine. Each magazine has a repeated pair of letters, and the same number of letters and they just look right on facing pages. I don’t think knowing that Rudder is a magazine about antique boats, and Vacuum is a magazine about atmospheric pressure diminishes that pleasure.

TH: What are some that didn’t make the cut but came close?

MF: There are some titles that are interesting, but were quite similar to others I decided to use on the same subject. I tried to avoid more common and contemporary magazines that are easily found on newsstands, like Mac World or Real Simple. I tried to choose titles that were a revelation for me, with the hope that they will be unfamiliar to others as well, and possibly worthy of further investigation.

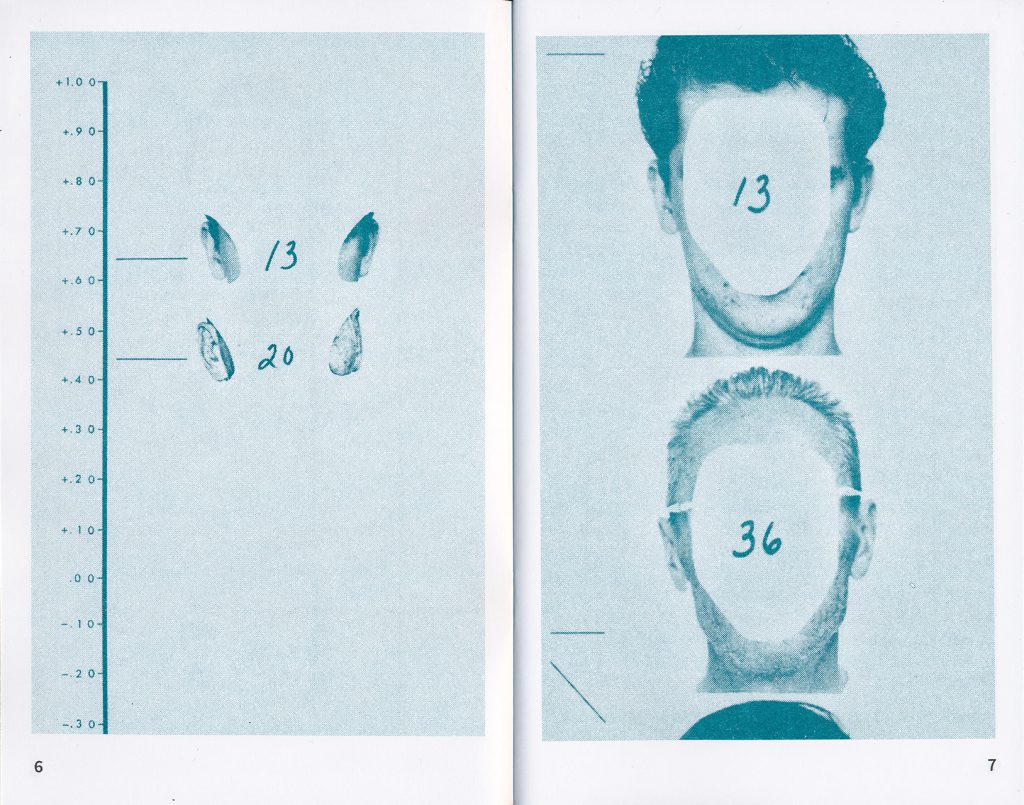

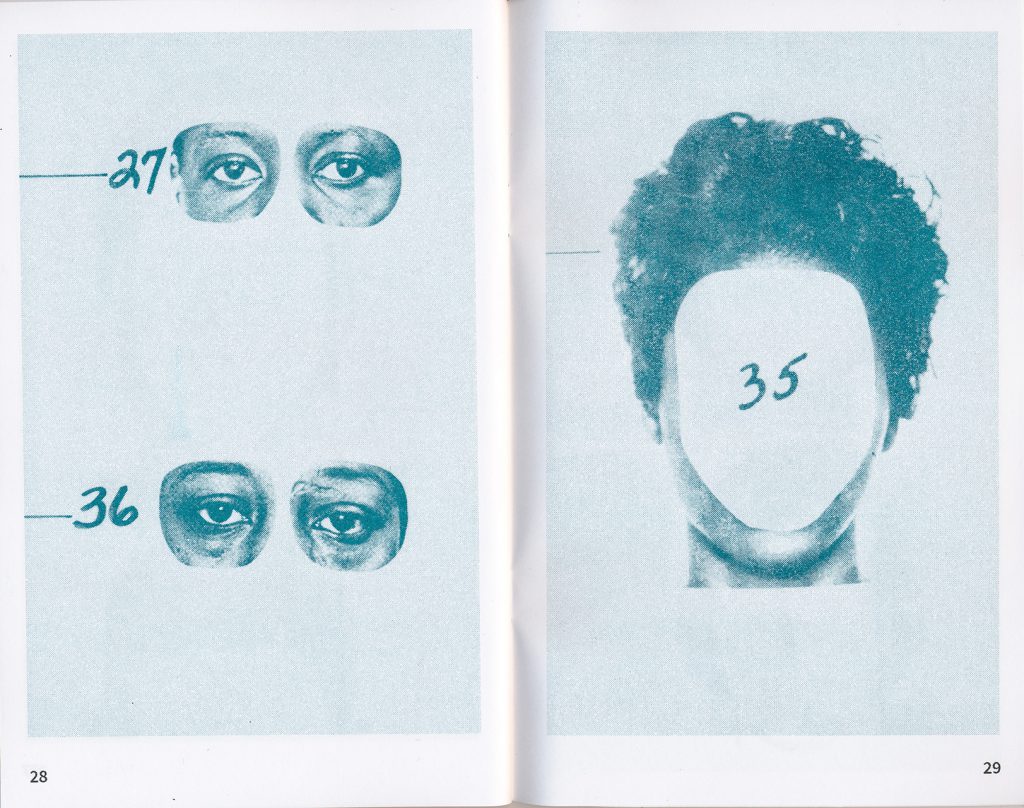

TH: Where do I even begin with Subject Methodology, the fourth in the series? What went through your mind when you found that book and as you flipped through its pages?

MF: In recent months, I’ve been spending a fair amount of time in the reference collection devoted to subjects like crime, policing, and incarceration. I often use the library as a kind of meditative space and like many people, I’ve been thinking a lot about police violence. Vast resources keep getting allocated for a militarized police force, while other areas in need like schools and mental health are being cut. It’s hard to avoid feeling complete despair, even when looking at something like this study that is over four decades old.

TH: The brief text you provide on the back cover poses some important questions about the violent nature of research, using the study that produced the book–a study conducted using mugshots from Erie County Sheriff’s Department in New York with students at Buffalo State College–as the tool to illustrate your point. Can you expand on this? Why was important for you to make this connection between contemporary concerns with our police state in 2016 and a study conducted 44 years ago?

MF: This is an excerpt of what I wrote on the back cover:

This booklet highlights the violence of the researchers’ methodology. The people in these photos were turned into a collection of parts—scalped, fragmented, beheaded, and sorted by race and gender. The study’s aim was to help witnesses identify suspects more accurately, and help law enforcement personnel do a better job eliciting information from witnesses. Over forty years later, fear-based and prejudicial eyewitness accounts have produced thousands of false arrests, wrongful convictions, and deaths at the hands of police. I support activists who are calling for the end of both police violence and law enforcement used for social control. We need community solutions for transformative justice, not more police.

Not a single police officer was convicted of murder charges in 2014 or 2015. Police killed over 1000 people in the U.S. in 2016. Police have all kinds of equipment like body cameras and surveillance tools that they did not have in 1972, but it hasn’t stopped them from shooting suspects in the back and it hasn’t led to increased convictions when cops kill.

The booklet is more of a visceral response and the source material has a vicious quality that feels consistent with how America polices its people. The tone of the study materials feels like Chicago in 2016 to me. As a society, instead of figuring out if we can match the shape of an ear to a hairstyle, or whatever the hell this study was after, we should be more worried about why we rush to call the police every time we see behavior that concerns us, why we don’t know our neighbors, and why so many people feel that punishment is the answer to wrongdoing.

All of the publications in this article are available for purchase nationally and globally. Find the Library Excavations series and more publications by Temporary Services and Public Collectors at halfletterpress.com.

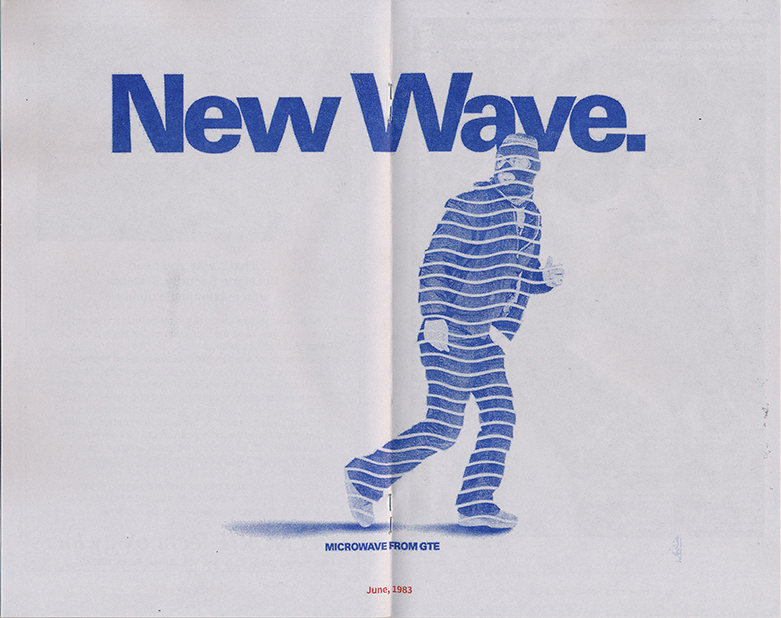

Featured Image: From Library Excavations #1: Correctional Advertising 1979-1989, Public Collectors, 2016. (Image courtesy of Public Collectors.)

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published in the Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists and exhibition catalogues. tempestthazel.com