A century’s legacy of Black designers working at the nexus of the quotidian, politics, history, and market capitalism is brought into focus through African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce and the Politics of Race, on view at the Chicago Cultural Center until March 3, 2019. The show’s objects and design content show generations of Black designers fusing a shared past and visions of the future within their historical contexts. This chronicle highlights designers and artists producing in many mediums including Charles Dawson, Charles White, Jay Jackson, Zelda “Jackie” Ormes, Charles Harrison, LeRoy Winbush, William McBride, Sylvia (Laini) Abernathy, and Emmett McBain. Particular emphasis is given to how 20th century Black designers and artists in Chicago reframed the conception of the Black consumer within the market economy. By the same token, the concerns, aesthetics, pressures, and values of Chicago’s dynamic Black communities are embedded in each object. Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs expressed this responsiveness when discussing the origins of the South Side Community Arts Center, quoted in the exhibition materials: “As young black artists, we looked around and recorded in our various media what we saw…They were the people around us…We were part of them. They were us.”

The creative imperative to address both the past and the possible has been taken up by many practitioners working in Chicago today, from Amanda Williams and Andres L. Hernandez, to Folayemi Wilson and Norman Teague, to Robert E. Paige (whose work is included in the show), and D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem, who spoke with me about the exhibition’s resonances in her own work and career. Duyst-Akpem is a polymath, engaging in fine arts, performance, design, education with an indefatigable syncretism that is deeply invested in Afro-Futurism, ritual, and ecology. As well as teaching a course centered on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower at SAIC, Duyst-Akpem has recently performed as a participant in the Decolonizing Mars/Becoming Interplanetary symposium at the Library of Congress, and contributed performance-lecture-poetics for “Afro-Futurism and Time Travel” at the University of Chicago’s Gray Center for Art and Inquiry. Her work consistently folds in an appreciation for the past material culture with future visions, conveying these amalgamations to us in our time.

“I come to it very much through an Afro-Futurist portal, it’s a real melding: a shift in space-time, it’s a melding of past/present/future, so when I think about my design practice and my work, it has to do with honoring Ancestors, both living and past, who have gone before, and the traditions that have been established. Just like I do with my poetry and performance lectures, I see it as a kind of a riff, almost a poetic riff within design on what has gone before,” Duyst-Akpem shared. She described the value she finds in grounding her work within historical lineages, an urge evident in the materials on display: “I see [my practice] as a kind of a conceptual collage so that when you look at a piece that I’ve done or you look at a space, every single thing has been considered with references to the past or some kind of implied intention force for a transformation in the future.”

As part of her manifold practice, Duyst-Akpem founded Denenge Design and In The Luscious Garden (launching in spring, 2019), focused on holistic and conceptual modes in human-centered design. Her works in these iterations take on interiors, costumes, site-specific installations, and many other forms, reflecting the fluidity of ambition and application that African American Designers in Chicago underlines. I asked Duyst-Akpem about how she navigates the assumed fissures between fine art and client-facing design production – similar pressures to those that the mid-century design practitioners showcased in the exhibition (operating in a society shaped by the Civil Rights and Black Power movements) faced in wanting to be responsive to the concerns of their clients and communities. In response, she told me about one of her earliest projects: “I really love responding to the client – that’s something that brings me a lot of joy. One of the earliest sculptures that I did, pre-grad school, was for Steve Miller of Origin Ventures and it was an eight-foot light sculpture which was based on a sound wave. He had spoken a line from a song, a lyric that was very meaningful to him, and it was one of the most beautiful experiences I have ever had working on a project; it was very affirming for me as an emerging artist…I like the parameters that a client-specific focus brings because I can do or build anything – do you need a cabin, do you need a spaceship, do you need a ballgown, what do you need? I have a lot of skills, so my thing is I’ve got my work [and] I’ve got my performances… and I’m building a huge body of work with that. But when it comes to the client, I love to be able to manifest. I almost feel like I know they’re sort of renting my eyes, and my vision, and my hands, but at the same time it feels like they’re working through me.”

Duyst-Akpem and I lingered over a vitrine that showcases the advent of mass marketing of Black beauty products alongside other visitors to the exhibition, peering at the magazine advertisements, promotional materials, and product tins that entered the marketplace at the beginning of the 20th century. Each of us was taken by the alluring images of smiling women and Egyptian motifs, markers of the way that Black commercial artists used consumerism to address historical notions of beauty and the personal intimate space. The objects resonated with Duyst-Akpem: “They are little works of art that become part of you…You think about starting your day with Slick Black, and Lucky Brown and what that means, Sweet Georgia Brown, African Hairdressers, Her Majesty, the Poro Graduate High Priestess of Beauty – those kinds of references are affirmations and they’re works of art that become part of your daily life. The role of design in [these products] is so important in thinking about whether those are spaces of affirmation of Black women’s beauty.” These ideas are also germs for Duyst-Akpem’s future projects with a particular environmental focus, as with an upcoming book in the Art After Nature series edited by Giovanni Aloi and Caroline Picard: “[I’m] thinking about these ideas of health, and how do we design and think about ourselves, the client, the materiality of the products that we’re creating – how do we put it out into the world in a way that will give credit to those who we’re influenced by, as well as credit to those who are creating this work? You know I’m very big on giving credit where credit is due. This is where I’m moving – it’s really about health and beauty and affirmation.”

In an essay that accompanies the exhibition, its co-curator, Chris Dingwall, makes note of Jae Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suit and articulates the role of Black women artists and designers working in Chicago in the late 1960s and early 1970s: “In important ways, the design practices of AfriCOBRA and the Black Arts Movement were directed by the talents and politics of black women…In Chicago’s Black Arts Movement, Jarrell, [Barbara] Jones-Hogu and [Sylvia (Laini)] Abernathy put the social and cultural needs of black women – long the domain of largely invisible milliners, hairdressers and seamstresses – on the agenda of African American art and design.” The concerns that guided AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) animate Duyst-Akpem’s current work, The Camo Coat, part of the Osanyin Commemorative Project, an extension of an endeavor that she began as a participant in a 2014 NEH Institute for Black Aesthetics and Sacred Systems.

Duyst-Akpem recounted the genesis of The Camo Coat to me: “The design of my Camo Coat is not only utilitarian but I was deeply inspired by the fact that this was a garment referencing [Jae Jarrell’s] design history here in Chicago, Jae of Hyde Park, and the fact that Revolutionary Suit…was a tweed garment, a little mini skirt with top, that had the bandolier with the reference to the bullets so that you could go to the office and also be prepared for revolution. I was really inspired with that, and in thinking about the Yoruba god Osanyin who is the Orisha of leaves and healing and forest, who’s often depicted as half-figure, half-tree, as if merging with nature and emerging from it. I was thinking about what it means to be protected, especially in Chicago, and that’s where The Camo Coat also came from…[it’s] about spiritual and physical protection. And it’s in development to include bullet-proof and Chicago-specific elements so that I could actually be both protected and camouflaged into Chicago. Thinking about the bullet-proof elements that would be included, I live just down the street from Mercy Hospital, so there are facets like that that for me really reference the work that Jae was doing…[as] the conceptual and the practical aspects all merge.”

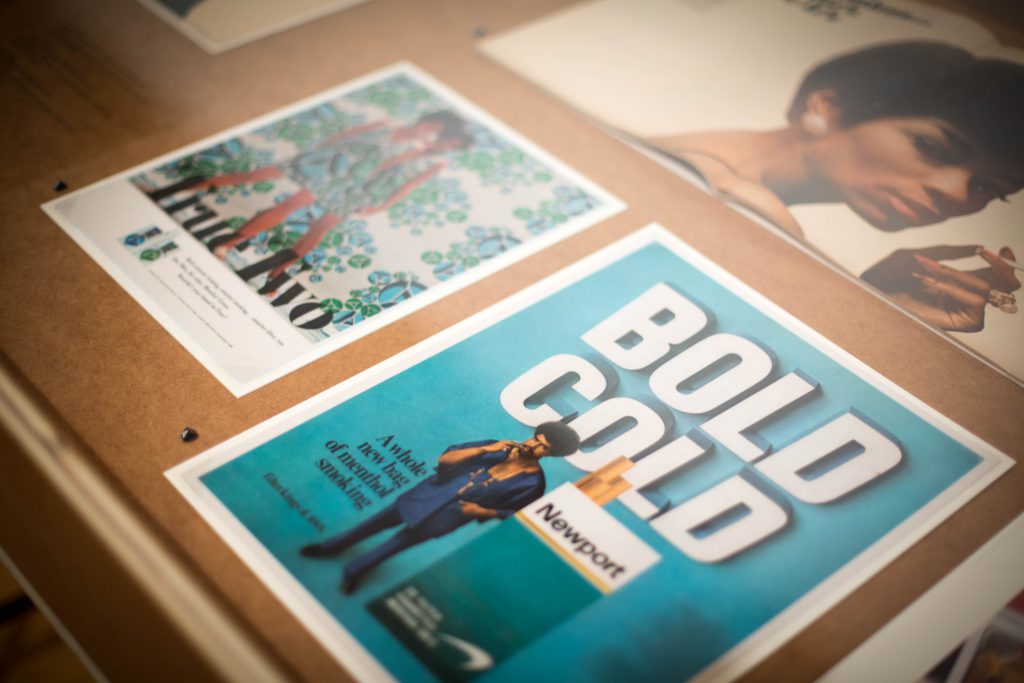

Works like Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suit confront the consumptive/acquisitive nature of market capitalist systems in the art world and beyond. AfriCOBRA, the Organization of Black American Culture, and the Black Arts Movement were wary of engaging in consumer society because they saw it is as inextricably linked to structural American racism. At the same time, post-war designers like Tom Miller and Emmett McBain, who worked on corporate accounts for 7-Up and McDonald’s, respectively, engaged the mainstream culture more directly in seeking to support Black communities’ concerns. Duyst-Akpem, who is in contact with Jarrell, is compelled to continue her practice in Chicago in a manner that privileges interactivity across various mediums and between different communities and sectors of the creative profession, all while sustaining herself: “The point is, how do we understand function? And for me it is [about] completing the functions thus far that I have set for myself which are largely to do with an energetic, emotional, and spiritual need.”

Duyst-Akpem and her contemporaries move forward in “the search for joy and permanence in beautiful things,” the definition of design offered by Chris Dingwall in his essay. This need for sustenance – of self, communities, institutions, political frameworks, and histories – remains central to the creative endeavor in Chicago as elsewhere.

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org.

Featured Image: D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem standing in front of “When Styling” (1973), a screenprint by Barbara Jones-Hogu at the exhibition African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce and the Politics of Race at the Chicago Cultural Center. Photo by Ireashia Bennett.

Noor Shawaf is a freelance editor, most recently on Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the Twenty-First Century by Barbara Ransby (University of California Press, 2018), and an editor for Sixty Inches From Center. Noor is a staff member of the National Women’s Studies Association.

Noor Shawaf is a freelance editor, most recently on Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the Twenty-First Century by Barbara Ransby (University of California Press, 2018), and an editor for Sixty Inches From Center. Noor is a staff member of the National Women’s Studies Association.