Allison Lacher and Jeff Robinson work collaboratively as artist-curators and organizers in Springfield, Illinois. For over seven years, they have developed contemporary arts programming at the University of Illinois Springfield Visual Arts Gallery, DEMO Project, and the Terrain Biennial at Enos Park. Lacher and Robinson reached out to seven creative and cultural purveyors whom they have worked with over their tenure in the capital city to reflect on their experience there — that is to say, “here.” The resulting texts together form “You are Here,” a new venture from the collaborative duo in partnership with Sixty Regional and made possible with support from Illinois Humanities. As is typical of their curatorial approach, Lacher and Robinson have extended freedom and latitude to each contributor, resulting in texts that take a variety of forms and offer wide-ranging glimpses into what it is like to work here in the flyover region of the United States, in the perceived rural Midwest, in Central Illinois, and, at the heart, here in Springfield.

Summer Love in Springfield

by Nick Wylie / Elmer Ellsworth

I left Chicago last summer to live in Springfield, where I would set down a path that would end in a lonely, touring coffin. Having worked for years making space for folks to hone their skills, this was the first time I was invited to be the recipient of such luxurious time to train. I had been invited to come study the big heart that pumped blood into one of the country’s most peculiar big brains.

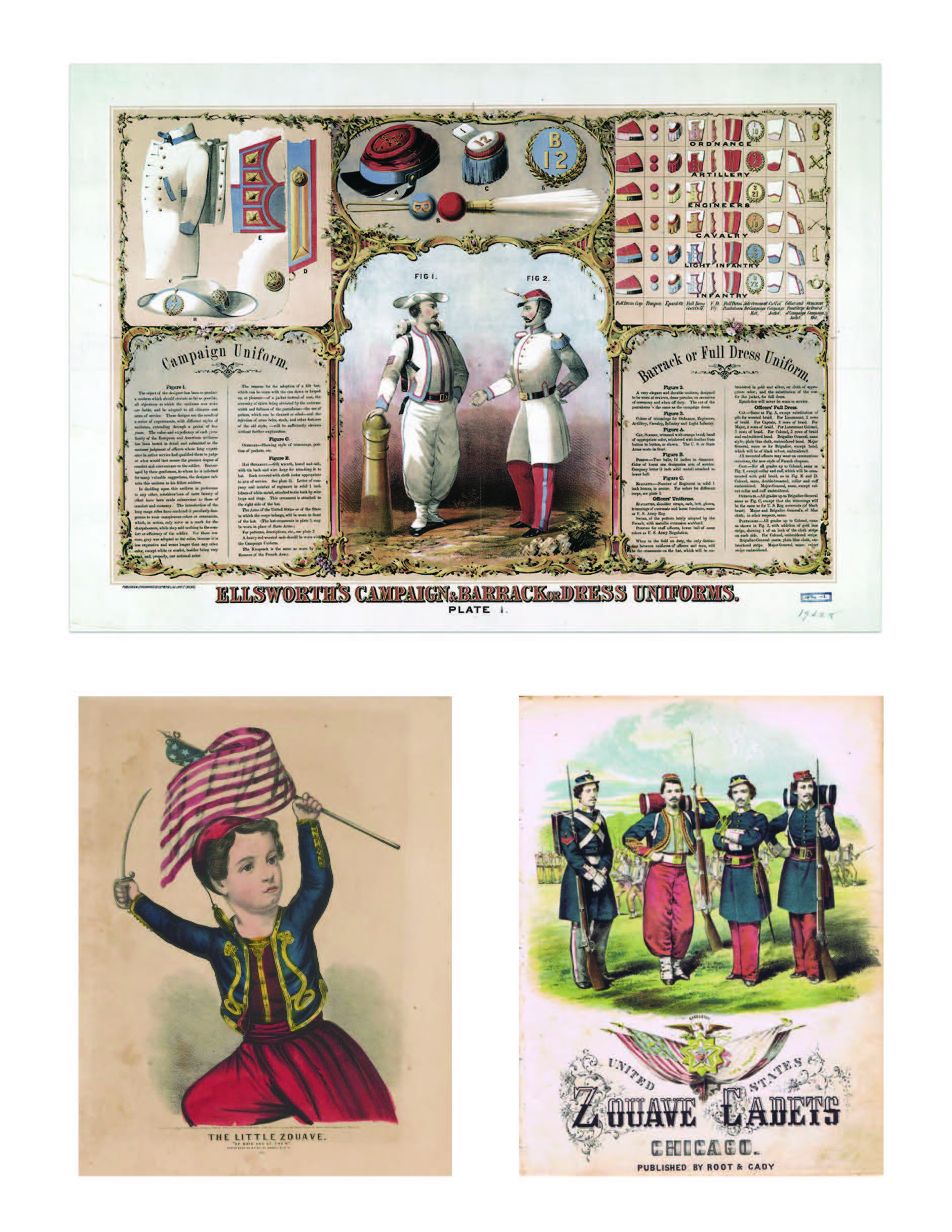

I’d only been to Springfield once before, having stopped there briefly the previous year; it was our last stop before home on a cross-country tour. My young comrades and I had travelled through the night, and gave a punchy performance for the Springfieldians we had the pleasure of finding solidarity with. Our visit was mostly about the celebration of the elaborately-festooned Chicago Zouaves–the young, athletic, teetotaling militiamen trained to fight in the acrobatic style and colorful uniforms of the Algerian soldiers of the same name. Their triumphal drill routines had drawn massive crowds at cities all across the North.

Abe was there, in the distance of the shady downtown park, watching us. I caught his eye, I think, and my return became inevitable. Springfield institutions beckoned me back, but I could feel his machinations behind the gears of their outreach, and was intrigued, wondering if his motivations lay in the special kind of friendship men like him had few words for in 1858. My longer, sweaty, summertime stay in Little Egypt would confirm my (hopeful?) suspicions about Abe’s camaraderie.

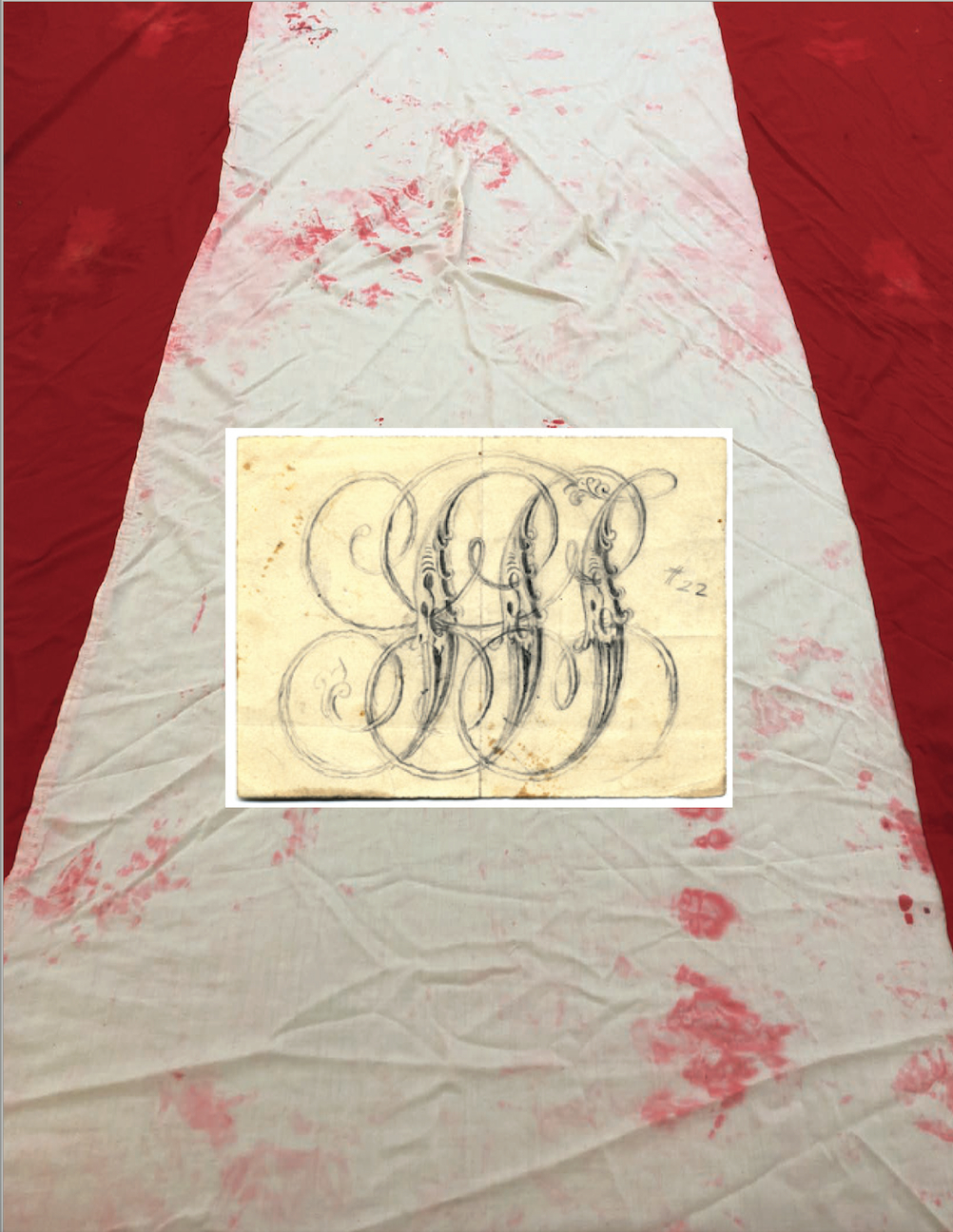

When I arrived in the capitol, I was put up in a lavish house, and fell asleep listening to his words, receiving the gifts of his favorite poetry. I spent time poring over the tomes that he had read, and sketching his portrait in pink. I was enamored of his Janus face, which as I studied it constantly vibrated idealistic good humor and stoic melancholy, never even alighting on one or the other.

I was immediately and repeatedly welcomed as a guest into the palatial (four bedrooms!) Edwards House. There, Abe and Mary’s engagement had been brokered, then broken, then eventually repaired. Unhappy marriages and their attendant trysts echoed through the house’s halls. “Gay” didn’t exist as a big clunky term for my love’s tendency yet, but upstairs there’s a painting of a Springfield woman holding a monkey in Paris, marking the time that Gertrude would coin the usage while describing her.

My very first day in town I joined a street festival as one of the featured guests. I scanned the scruffy, nondescript faces of local residents and found a much more discreet etiquette than I had become accustomed to in the big cities where I’d shared the company of men. My attendance to the fair drew reporters’ and historians’ attention, and I participated in interviews with each. The reporters put words in my mouth a bit, but their interest was flattering. The older historians looked angrily away from the lavender and utopian streaks their heroes once displayed. The younger ones were proud of their ambivalence in the matter. Fence sitters are worse than our enemies, someone once said.

I learned of an organizing dynamo and his plans to conduct a huge parade through the streets of Springfield with those secretive, nocturnal abolitionists The Wide Awakes. Appraising this as the spectacular and urgent project that it was, I readily jumped in to support with my Zouave comrades. We introduced some of the more queer pageantry to the solemn procession of citizens ready to march into the poisoned lands of our nation and stop their hateful behavior and false heroes. After the parade, walking late at night in the Springfield streets, I saw a large flag for their corrupt cause and almost took it down; I’ll be braver next time.

I grew closer to Abe as I discovered our common cause: tearing down the pig system. I was compelled by his affiliation with the ideas of his correspondent Karl, regular contributor to The New York Tribune. That paper became our joint education, and would go on to publish a call to gather the imperial city’s most handsome firefighters to train for war as the Fire Zouaves. Abe’s friends in St Louis, Hegelians 48er, expanded my mind about what a second American revolution could look like, and reinforced in my chest the inevitability of that approaching violent justice. Thinking through how the world might radically be transformed by the will of the oppressed made visions of liberation dance before our eyes; occasionally our eyes would meet and share a glazed flash of that fire.

Our masculinities through time have shifted, I keep being told, but it’s hard to know how much, and whether we’ve seen progress or regression in the ways that men can know each other. Language is still not available to describe positively what swells in our chests as camaraderie and fraternity expand into something more. Maybe Walt’s words contain a clue or two–“special friends?”

I continue to wonder what to call the feelings like what I shared with men like Abe; are they the same as the love that Abe had for his lost companion Joshua? The discretion of these Springfield men is exasperating, but intimate in its privacy. I keep puzzling over Abe’s favorite poem, which dreams of being buried together. He never tired of reciting to me these morbid verses from Knox, so seemingly chiding the prospects of progress we held sacred:

For we are the same our fathers have been;

We see the same sights our fathers have seen;

We drink the same stream, we view the same sun,

And run the same course our fathers have run.

Could there be no way that he and I, or he and Joshua, would ever be buried together? His burial with Mary Todd feels like almost a profanely exposed, pathetic gesture. Wouldn’t be bad to lay for a long time in the dirt with a man like that though, when our work is done.

Conceiving of a way that a man could publicly share the White House’s presidential bedroom with his groom strains my imagination. It has never happened, and most people likely haven’t had a glancing thought about the naturalness of it. I daydream: Would we be a power couple, enacting Mary’s unmet desire for co-leadership? Or would we be like the Revolution’s noble Baron von Steuben and one of his loyal soldiers? Are we all really the same as our fathers have been? This mayor from Indiana, distasteful as he is to me, makes me wonder if it would really be all that different. Michel misses the very outlaw-ness of our discretion, and the public cheek-pecking that we saw on that South Bend stage did nothing to stir my heart.

Culture’s conditions frame or ignore what might be the same feelings before the going semiotics twist them into shame or mundanity. Having language to describe how an ancestor felt when he shared intimacies with another man, during the lead up to some other war, is a task that comes with built-in vertigo, that effect you get by simultaneously dollying in and zooming out. Putting oneself squarely in those old, uncomfortable shoes is a precarious endeavor, but there are maybe useful things we dropped back there, and we should return to look for them, wobbly footing or sure.

Featured Image: A portrait of Elmer Ellsworth that the artist painted in the street in Springfield, July 2018. The mainly black-and-white portrait depicts Ellsworth in formal attire, with text that says “Elmer Ellsworth 1837-1861”. The image is surrounded by a yellow border and rainbow-colored text that says “discreet”, which refers to the “category” that the majority of queer Springfield men select on dating apps. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Nicholas Wylie is an administrator and educator based in Chicago, where he is currently Managing Director of Public Media Institute. In 2006 he co-founded Harold Arts, a Chicago-based non-profit art and music organization with a residency in Ohio, and was its co-director until early 2010. He then co-founded ACRE (Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions), a 501(c)3 with residency in rural Wisconsin and an extensive exhibitions program in Chicago. Wylie served as co-director of ACRE until joining its Board of Directors in 2015, after moving to San Francisco to serve as Associate Director of Southern Exposure, an established visual art and education institution in The Mission. Wylie was also Founding Artistic Director at Mana Contemporary Chicago from 2012-2015. He has taught artmaking and arts administration courses at Chicago High School for the Arts, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, and University of St. Francis.