I met Angelique Power while I was interning in the development department at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2010. Although she wasn’t in that department, I can clearly remember the times I shared a room with her. The first time was during a meeting that she masterfully managed, keeping things clear and on-point, with everyone there leaving with their marching orders on how to move things forward. I never thought I could have such a transformative experience in something as basic as a staff meeting, but I was in complete awe. The determined spirit that led me to the office and classroom doorways of my Columbia College teachers and professors was the same spirit that helped me gather the confidence to step into hers.

Since then she has been a steady voice of reason and sound advice–which over the years has manifested as a consistent and piercing blend of love, logic, and honest but compassionate interrogation of self and others. And it is because of her guidance that I have stepped into easily the most challenging yet rewarding position I’ve held, now as the Arts Program Officer at the Field Foundation. I learn from her and her leadership daily and, once again, stand in awe of her as she dismantles, disrupts, and helps to seed a new vision for the world of philanthropy.

Here she shares one of her most influential teachers who she met early in life. This response has been edited for clarity and length.

Angelique Power

My most influential teacher was my Rabbi Arnold Jacob Wolf. I met him at KAM Isaiah Israel, my temple. He was an older man, short, bent forward, with the voice and heart of a lion – or I suppose a wolf.

When I was in seventh grade, thirteen years old, I was in a confirmation class at temple with Rabbi Wolf. Rabbi Wolf was one of the first grownups to talk to me and others in the class as if we were grown ups ourselves. He questioned our thinking, made us defend our ideas, and didn’t expect us to answer in the way we thought he wanted us to–he expected us to think first and answer with our own ideas.

I remember timidly asking him what it meant to be Jewish. As the only brown girl in that class I wondered if Jewishness had to do with how you looked, how you talked, what you ate, how you sounded. At thirteen I wasn’t sure I even believed in G-d. I told him that too.

He told me being a Jew meant asking tough questions and taking care of your neighbor. “Are you doing this?” he questioned. “Yes,” I answered. “Well, then you are a good Jew,” he concluded.

That same year, Rabbi Wolf wrote a memo in the Temple Bulletin where he made a list of the top ten reasons that Russia was a problematic country. At the end he said we should replace the word Russia with Israel. You better believe the volume was loud on those calling for his removal. But he wasn’t removed. He kept writing and speaking and asking tough questions and taking care of his neighbors. (And the temple was full each week, with perhaps as many naysayers as believers – but whether people hated him or loved him, they came to be in community to hear what he had to say.)

Lessons Learned:

Be honest and bold with your honesty. Ask good questions. Take care of your neighbors. Understand your worth by your actions, not your appearance. Others believe in you, even in times you may not. Trust them.

_

This article is part of a larger article called Who Are Your Teachers?: After Richard Hunt at the Koehnline Museum of Art, which features several Chicago artists and workers who have been influential in the life and work of Sixty co-founder Tempestt Hazel.

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org.

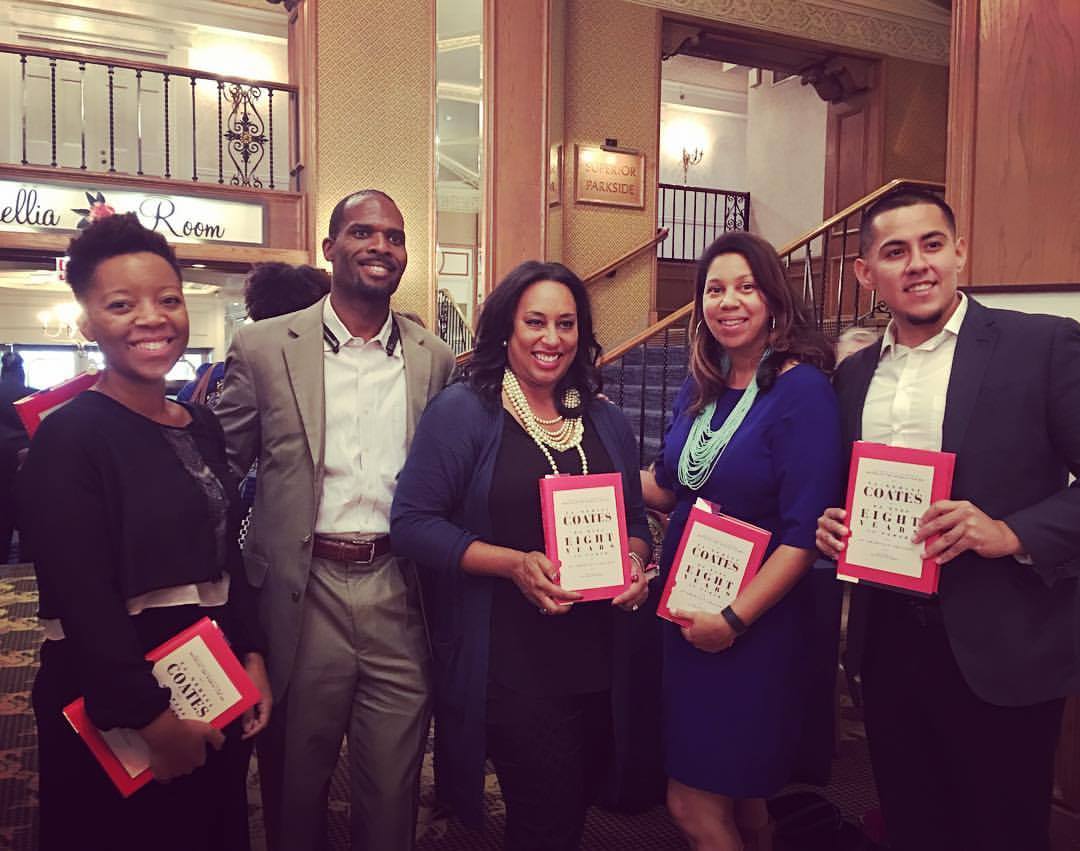

Featured Image: My first week at the Field Foundation, attending a luncheon where Ta-Nehisi Coates was in conversation with Alex Kotlowitz. Angelique Power is the second person from the right, surrounded by Jawanza Malone (left), Senator Toi Hutchinson, and Berto Aguayo (right).

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. You can also read her writing in the upcoming Art AIDS America catalogue for Chicago and the online journal Exhibitions on the Cusp by Tremaine Foundation. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Darryl DeAngelo Terrell.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Her writing has been published by Hyde Park Art Center the Broad Museum (Lansing), in Support Networks: Chicago Social Practice History Series, Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual, Unfurling: Explorations In Art, Activism and Archiving, on Artslant, as well as various monographs of artists, including Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s In the Company of Black published by Candor Arts. You can also read her writing in the upcoming Art AIDS America catalogue for Chicago and the online journal Exhibitions on the Cusp by Tremaine Foundation. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Darryl DeAngelo Terrell.