You’re invited to fill in the following sentences:

_______ holds ______.

_______ is really good at holding _______.

You asked _____ to hold ______ for you.

I feel ______ when I am held ______.

We could put a lot of things in the blank spaces of these sentences.

A mother holds their child.

My hand is really good at holding your hand.

You asked me to hold this for you.

I feel safe when I am held.

Holding, to hold, to be held involves two nouns: the thing holding and the thing being held.

Holding, to hold, to be held also involves a verb: it is an action, it exists in the doing and the receiving.

Sometimes this noun and verb also involve an abstraction:

My body holds pain.

This place holds a lot of memories.

These walls hold a home.

The ground held our hope that something would grow.

The ground held the grief of our loss.

On September 14, 2024, I attended a performance by Maria Plotnikova at the John David Mooney Foundation in Chicago, IL, titled Territory and People, which was described as, “a practical and metaphorical fight with the weight of trauma, the weight of violence, and the weight of survivor’s guilt.” Plotnikova goes on to state, “…This piece is my attempt to understand the war for the territory with one’s body, the physical reality of death of the other body, and the struggle of letting go.”

Ukrainian artist Maria Plotnikova was born in Zhytomyr, raised in Mariupol, and when the full-scale Russia-Ukraine war started in February 2022 Plotnikova was in Kyiv, but had to leave the country soon after. Plotnikova works primarily in painting and performance, is an MFA graduate of SAIC, and currently resides in Chicago.

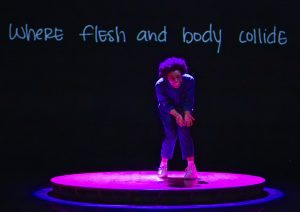

This iteration of Territory and People began as an installation of three sculptures. Each sculpture consisted of a pair of grey pants and a grey shirt, sewn together, then stuffed, with seams taut finally laid on the wooden floor of the gallery. When I entered the room the sculptures, while immobile and inanimate, had a presence about them—one that commanded attention and unease. They were body-sized. While they were three-dimensional; they spoke of death because they were void of hands, feet, or a face. While they were filled; rather than being hollow, they seemed to be holding absence. They spoke of the loss of a body, a body that wasn’t here anymore.

The performance began with Plotnikova crossing the floor, stopping to kneel beside, touch and then hold one of the sculptures. As Plotnikova’s body interacted with the sculptural body I sensed a shift in my own body. In their stagnant state, I found the sculptures to be almost gimmicky, like a scarecrow or a halloween decoration, but the minute Plotnikova held the sculpture’s arm and sand began to fall from its orifice everything changed for me: holding became an action.

I felt a weight pull down inside myself, the way a deep sigh drops your shoulders and pulls your chest down into gravity. Simultaneously, I felt a weight lift off of me, the way relief feels like wings and air. This push and pull of weight, held in my own body, was coming from the feeling of knowing, being seen by, and being invited into the work of Territory and People. This was a work about pain, struggle, and loss. This was a work about love, longing, and togetherness. The second the sand began to fall out of the cloth that had been holding it, I encountered a connection to the humanity embedded in the work. The push and pull of sinking weight and lifting weight held in my own body reminded me that bodies are capable of holding both care and destruction. Bodies are capable of holding both love and pain.

Territory and People began in the late Fall of 2021 and was first presented in Berlin at a time when anticipation of war was in the air in Ukraine. It had been building since the invasion of Crimea in February-March 2014 and now in Fall of 2021 the news was beginning to report increased tensions. Territory and People was first presented as a solo work with the intention of creating a visual image of the performer lifting a sculpture from the floor, the performer rising to their feet, and then the sand falling out of the sculpture to the ground in front of them. However, Plotnikova immediately realized that the weight of the sculptural body, the realities of physics, and the limitations of their own physicality meant that the desired direct action would be impossible. The sculptural body held too much weight, in fact it held too much dead weight. Yet, the reaction to the piece in Berlin was still incredibly charged—the audience froze, completely silent after the piece concluded, viewers stating that it felt as if someone had died.

In the Spring of 2022 in Spain, Territory and People was performed a second time. Plotnikova began rethinking the work in several ways. First, they introduced collaborators, performing the work as three people rather than as an individual solo. Second, due to the physical injury that had resulted from the first iteration, Plotnikova began rethinking their own body’s approach to and relationship with the body of the sculpture. A declarative action of lifting shifted to a dialogue-based action of crawling-under, and moving-with the body of the sculpture. Plotnikova began working with Ukrainian dancer and choreographer Alina Sokulska. In the same way that we need community to model healthier ways for us to grapple with and support us in our loss, watching Sokulska’s interactions with the heavy, sculptural-body as a dancer continue to inform Plotnikova’s movements in new iterations of Territory and People.

In the 2024 iteration of Territory and People performed in Chicago, Plotnikova was joined by former SAIC classmates Sofía Gabriel and Chia Chun Huang. Gabriel and Chun Huang each enter the space and, like Plotnikova, approach a sculpture, kneel beside, touch and then hold the sand body in front of them. All three of the performers continued to improvisationally move with, beside, and under the sand bodies: each making different choices about holding, pulling, turning, and touching the sculptures. I was immediately struck with the way tone and affect differed between each performer’s movements and the complexity that that brought to the emotional landscape and intensity of the work. The way Gabriel moved appeared to be influenced by dance: their slow movements, soft body and soft gaze brought a familial presence of care to their interactions with the sand body.

This was juxtaposed by Chun Huang’s attempts to pull the body across the floor or from the floor on top of their own body. Chun Huang’s arms and neck burst with tension, there was a shake in their jaw and cheek of their face, gasps for breath, sighs, and struggling groans. Each of the performers had moments of build-up to a point of release; and with all three duets happening simultaneously seemed to speak of differing, but parallelling journeys we have with grief and the varying realities we each know of war. There were moments when the sand body balanced perfectly atop Plotnikova. In a sort of “holding harmony”: the sand remained contained, its weight being held by the fabric and Plotnikova’s chest or leg or arm. Then there would be a tipping point: the weight of the sand would shift just slightly and be released, like a held breath, pouring onto the ground. Plotnikova noted that because there is little to no interaction between the performers, breath came up as “a possible way to unite us”.

When an artist creates, they bring parts of themselves to the work: pieces of their history, intention, narrative, and emotion become replicated, now held within the thing they’re creating. In performance-art repetition becomes a history of knowledge that a maker brings to the work and often changes the work for both maker and viewer. Likewise the Chicago iteration of Territory and People, Plotnikova’s body brought the memory of having done the piece multiple times before. On the other end of the spectrum, for Chun Huang and Gabriel, every movement, every shift of their body with the sculptural body was the first time. For Plotnikova, the history of having hurt their back during the first iteration (Berlin 2021) brought a reservation and apprehension that caused them to regulate their breathing, not letting their body hold too much tension, taking moments to pause, and pacing themselves as they held and moved with the sculptural body. While Plotnikova was critical of this, stating “I was too good. I knew too much. I was afraid to hurt myself,” I see these paralleled realities of engagement as an echo to variation in our own histories with grief and cultural contexts of war. The ways we hold loss within ourselves will always exist differently for different people. The way one body understands and experiences loss will exist differently over the course of their lifetime. There was an authenticity to the variation of each duet that allowed different points of access and challenge. There were times I felt personally connected to movements from one of the performers. Then in other times their movements seemed to be showing and telling me a reality that was outside of my own lived experience, and yet that they were equally as crucial to engage with.

Plotnikova talks about war and the differences of imagining war, vs. living with the possibility of war, vs. the reality of being inside of it and all the ways that we hold these different realities inside of ourselves. Discussing their calm approach to the performance Plotnikova goes on to state, “maybe this reality of having war in my country for three years made me less emotional”. When war begins suddenly everything is different: including you.

An artist and writer I deeply admire: Cecilia Vicuña, often speaks about precarity: as it relates to material, to humanity and to our present state. Vicuña describes a material’s connection to holding life but also holding death as a useful tool in engaging action and “as a connection and continued engagement with that action as a connection to a field of knowledge, a field of love and understanding.” Things still linger: in ourselves, in the soil, in the water, in migrating butterflies, in plastic, in our generational traumas, but also in our generational joys.

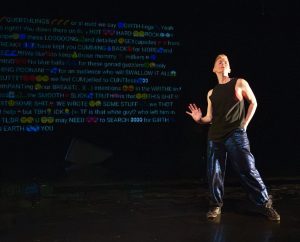

When I asked about the ways place and space affect the work of Territory and People, Plotnikova cited some of the differences between performing the work in Europe, where war still lingers in the air, vs. the United States where there is so much physical and emotional distance from war: war is always over there as we continue to go about our carefree daily lives. In the United States, any fear associated with war is contained within an imagined abstract possibility of some sudden apocalyptic and instantaneous action. Whereas, in a place like Spain after Franciso Franco’s dictatorship, there are the ways The Pact of Forgetting (forgive and forget) meant that neighbors continued to live in proximity to mass graves, and next to people that may have tortured and betrayed their family forty years ago. To perform the work of Territory and People in Spain meant the work interacted with the history held in that place and meant performing it for an audience that brought this history and lived reality inside of them.

Plotnikova talked about the lack of awareness and feigned innocence in the United States and how that changes how symbols are received, going on to mention zombies, horror movies, and people putting skeletons in their yards for Halloween. I was immediately pulled back to my initial reaction to seeing Plotnikova’s sculptures on the floor when I entered the gallery. In considering the logic of Plotnikova’s work, I had reduced the emotional weight of the presence of the sculptures in that first encounter because in my cultural context their symbolism had been desensitized. I didn’t come to Territory and People with a lived experience of the effects of war. Instead, an isolation from the effects of war (even though I live in a country that is deeply connected to war) meant an abstraction of and reduction of symbols of violence.

I first learned of the John David Mooney Foundation in Fall 2023 through performance artist Yaryna Shumskal who had traveled to Chicago from Lviv, Ukraine to teach a workshop I attended through the performance collective Out of Site Chicago. During a lecture at JDMF Shumskal spoke “about their artistic and life experiences after February 24, 2022 and the effects of the Russian aggression on the lives of their artistic friends in Ukraine.” During the Out of Site workshop Shumskal spoke of the ways war changes things you wouldn’t expect: like the sky. The field used to be a place you could relax in; you could look up at the sky and it would bring peace or reflection. However, now the sky was transformed into a place that brought fear, pain, and death. This brings to mind the similarity of the words hold and hole; they are linguistically similar and they differ by only one letter of the English alphabet; similarly, a whole can not exist without a hole. In many ways a hole becomes whole when it is held.

A year later, when I attended Territory and People, Plotnikova also highlighted the way in which war changes everything. Plotnikova encouraged the two other performers, Chun Huang and Gabriel, to bring themselves and the things they hold inside of them to the work: their own personal experiences with loss and pain. Yet, Plotnikova knows that the work will be read through a lens of it being about the war in Ukraine. For Plotnikova, their journey as an artist since the full-scale invasion from Russia in 2022, has gone from “what is art for”, to realizing that art can bring awareness, to exhaustion from the difficulties of engaging this topic while being so directly impacted by and inside of it. Now, Plotnikova accepts and even sees the importance of anything they make being read as political even if the origin of a piece begins from a more personal place. Considering the motif of horizontal-ness in Plotnikova’s work, it is not lost on me that hold and fold rhyme: a fold is when one thing is reshaped to be able to wrap around something else, allowing it to be a container that holds.

Many of Plotnikova’s pieces engage the tension that exists between both connection and separation. In discussing their work Sofa[r] (performed through SAIC in 2021) they state, “Can we ever actually really be together, even when there is no COVID, because of this border. We might want to be with someone but we still have this skin, and we can’t pass through that skin.” There is always this thing that connects us but also separates us, whether it is skin or war, or a pandemic, or someone dying.

In the piece Territory and People, the relationship of the performer to the sculptural body engages this tension of connection and separation. There are moments when the performer and the sculptural body seem to become one with each other, or as echoed by the writer Anne Carson “where do you stop and I begin”. There are moments of deep sensuality and care between the performer and the sculptural body. Then suddenly, the sand falls out, and we are immediately brought back to the ephemerality of being alive. It isn’t something we can actually grasp. As it slips through our fingers it becomes something that we hold and also always escapes being held. Considering this passage that Judith Butler states in Frames of War, complicates this dichotomy further.

“We can think about demarcating the human body through identifying its boundary, or in what form it is bound, but that is to miss the crucial fact that the body is, in certain ways and even inevitably, unbound— in its acting, its receptivity, in its speech, desire, and mobility. It is outside itself, in the world of others, in a space and time it does not control, and it not only exists in the vector of these relations, but as this very vector. In this sense, the body does not belong [solely] to itself.”

This boundlessness of the body and a constant grappling with connection and separation, come through finally in a prompt given by Plonikova to their fellow performers: “you have to believe that the sculptural body can be vertical”. As the forty minutes of Territory and People enfolded, I found myself, subconsciously, rooting for the performers to successfully be able to lift the entire sculptural body and it became more and more apparent that that was only going to happen when all of the sand had been removed. Everytime the sand would come out I experienced relief.

Plotnikova speaks of the knowledge our body contains of holding another person. Our lived experience of touch is primarily or exclusively with bodies that are alive and our memories and history have little context for interacting with bodies that are dead—this reality was important for the performers to maintain. This fight with horizontality and verticality is a tension we experience as an ephemeral species through love and loss. Therefore, this tension comes out as the performers attempt to make the sculptural body vertical and the impossibility of that.

As more and more sand was released, it began creating dust clouds in the air. Coupled with the rain-like-sound from the dust as it fell to the ground, this brought a connection to water and evaporation, as well as breath. As the dust exhaled from the sculptural body, held by the performer’s body, I inhaled deeply with my own body, held it for a moment, and sighed slowly to let it slip out again.

About the author: Rachel Lindsay-Snow is a Chicago-based artist and writer working in performance, installation, drawing, poetry, memoir, and essay. They received an MFA from UIUC in Visual Arts, with a graduate minor in Dance in 2020. They are a Luminarts Fellow with select solo shows at Krannert Art Museum, Swedish Covenant Hospital, North Park University, and The Front Gallery New Orleans. They are a member of Conscious Writers Collective and Out of Site Artist Collective.