This essay is published as part of Sixty’s Midwest Arts Writers Fellowship, a 6-month opportunity for writers to develop, refine, and publish writings on topics that are relevant to Indigenous, trans, queer, diasporic, and/or disabled artists and arts workers in our region. Each Fellow will publish two essays that reflect on the complexities of Midwest life and the artists who help define and articulate its culture. Read more writing by the Fellows here.

“I aspire to be a teller of universal truths,” my grandmother once said. Yet her story—a true story—was one I could never quite believe. When my grandfather met my grandma, he was already engaged to another woman; his mom even approved. When his fiancée went home for the summer, my grandpa fell in love with—and in awe of—my grandma. She was beautiful, cultured, and a year older than him. When he came clean about being engaged, my grandmother dumped him. He then confessed to his fiancée, called off their marriage, and somehow, won my grandmother back.

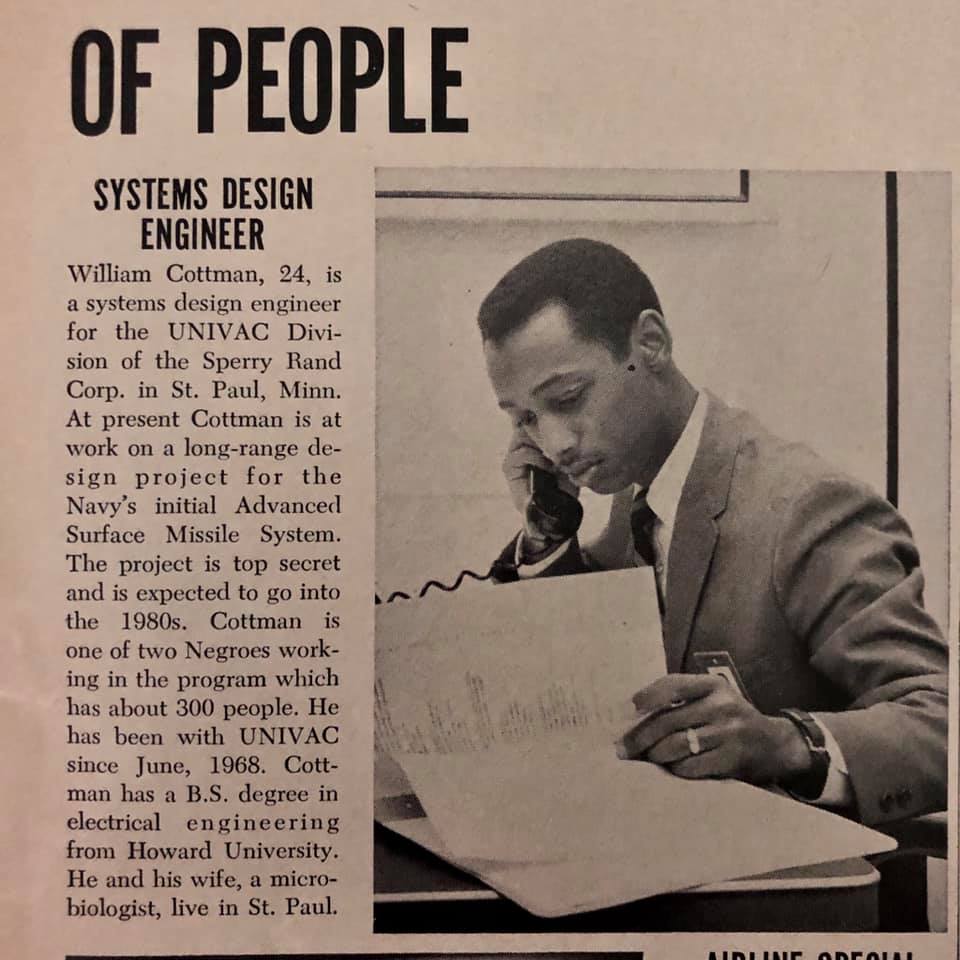

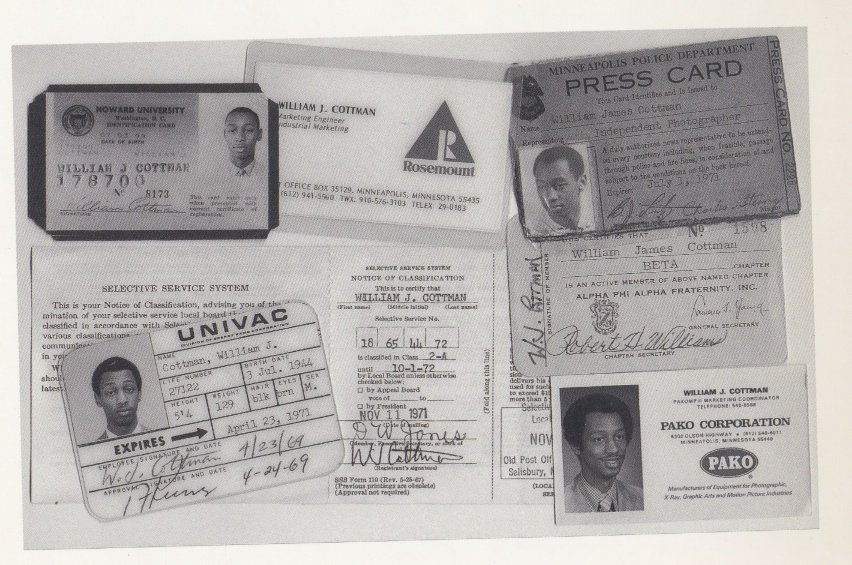

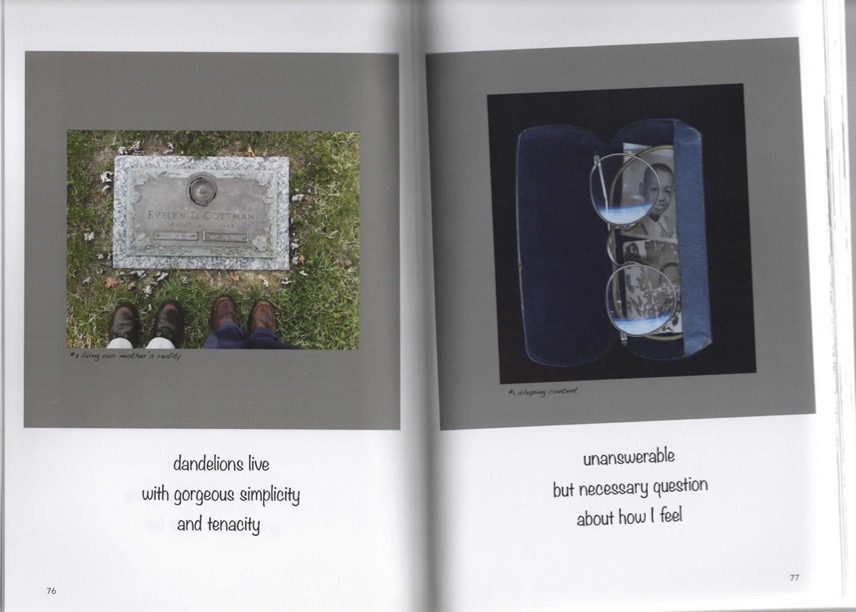

They married on June 10th, 1967, and the day before that, graduated from Howard University in Washington D.C. My grandfather William “Bill” Cottman, son of Evelyn Cottman, enrolled at the school of Engineering and Architecture, and my grandmother Beverly Delores Walton studied postgraduate Microbiology. They arrived in Minnesota on June 11th, 1967. Their move, as I had liked to imagine it, was not done on a romantic whim. My grandpa had secured a job with Univac Federal Systems as an engineer immediately upon graduation. The apartment they moved to on Davern St. on the outskirts of St. Paul, off West 7th, was within walking distance to the job.

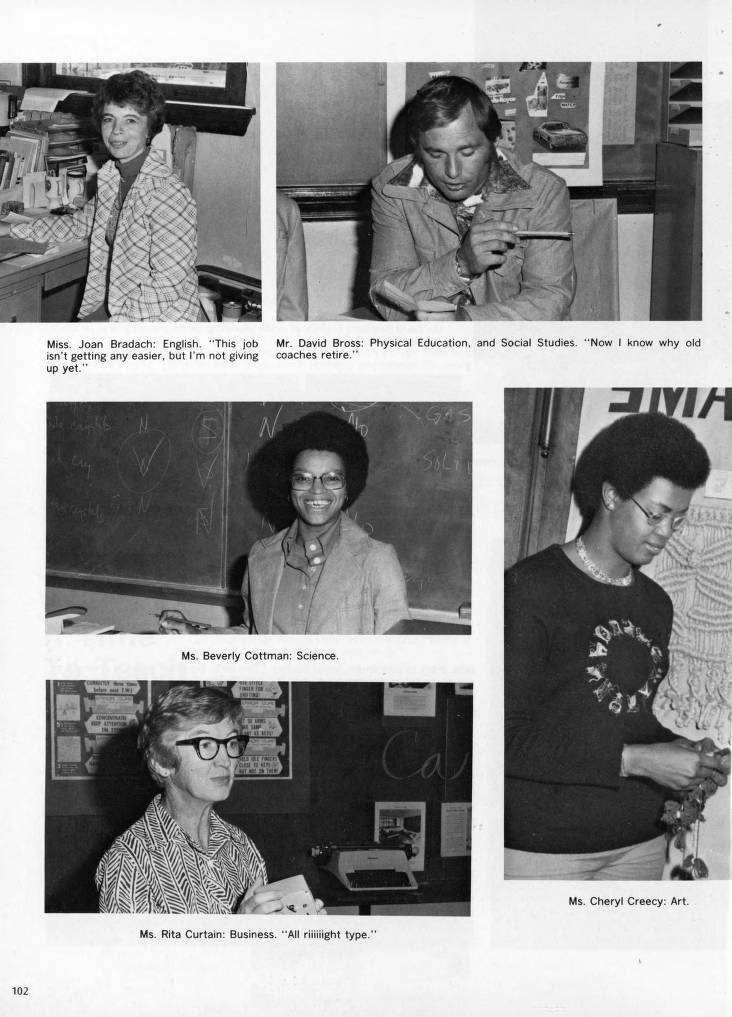

My grandmother adjusted her plans, as she’d left in the middle of her studies at Howard for the wedding. She obtained a Masters in Secondary Education and Teaching at the College of St. Thomas. She made quick work of her degrees and became employed as a teacher at and Marshall U High School in Northeast Minneapolis.

Prior to meeting each other, my grandparents had both toyed with the idea of being artists. Those ideas took a backseat as they stabilized themselves in traditional careers. However, creativity would soon become a part of their life together, rather than a making of it. My grandma joined a community theater group. She landed roles in Hair, Cabaret, and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. She dipped her fingers into pottery and painting, and her toes into ballet, African, and modern dance.

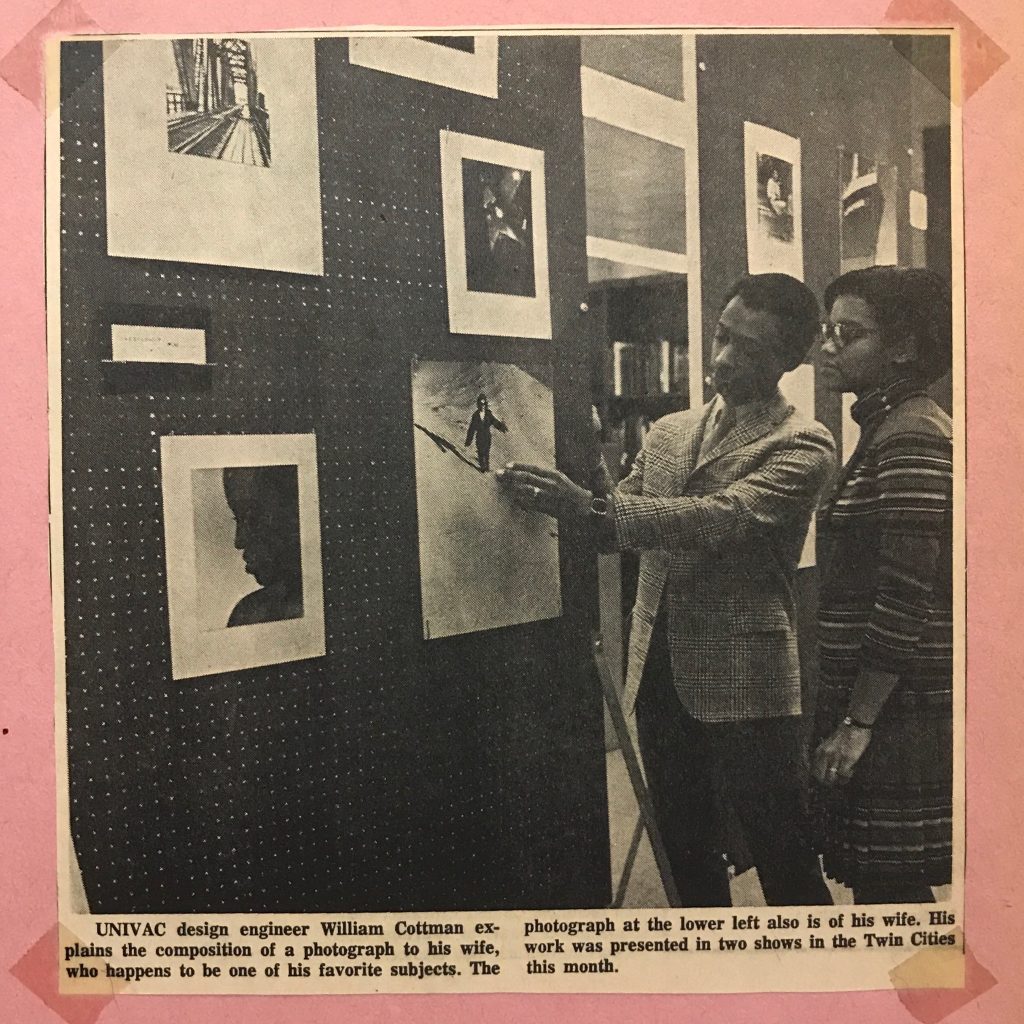

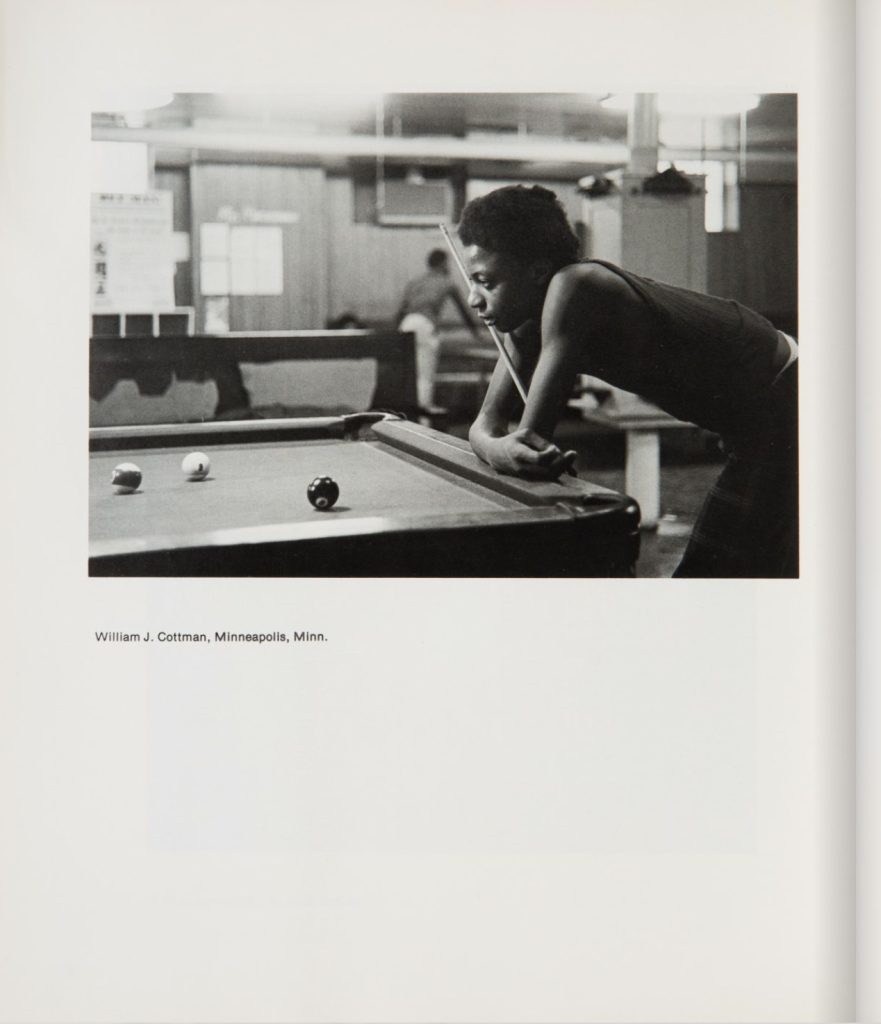

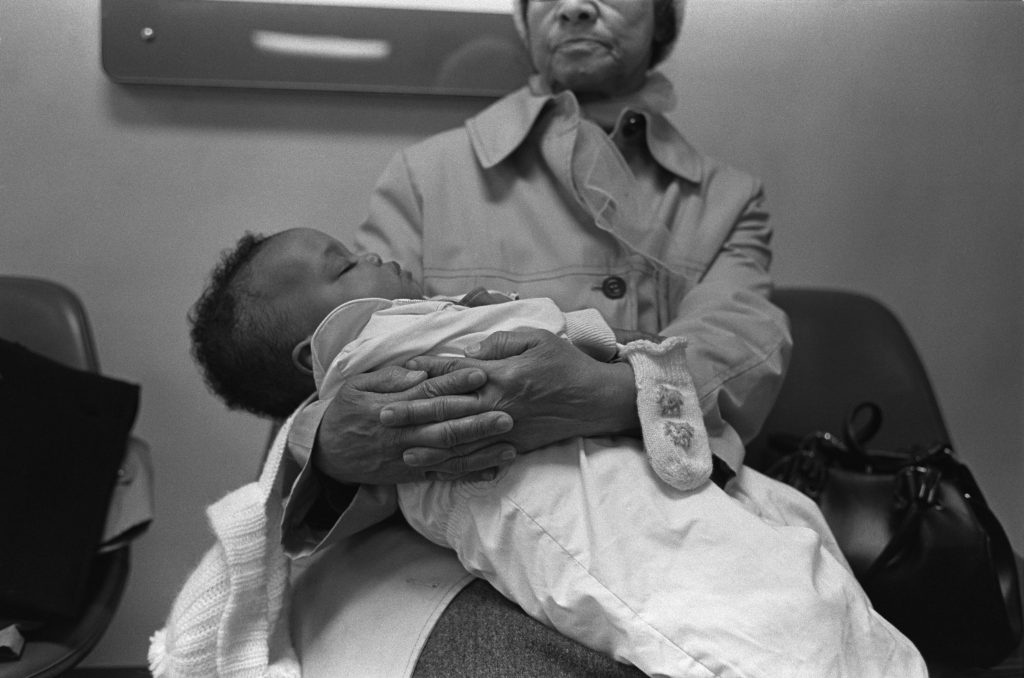

My grandpa ruminated on commercial photography. The technical aspect of developing photos interested his engineer mind, and it was “quicker than painting.” His interest was realized when his downstairs neighbor looped him in with the camera club at the Hallie Q. Brown community center on Aurora and Mackubin. At the club he was introduced to ideas about the “right” way to do things from black and white traditionalists, and sold photos at the library and Uptown Art Fair. During this time, he experimented with developing his own color photos at home, in a walk-in closet he converted to a darkroom.

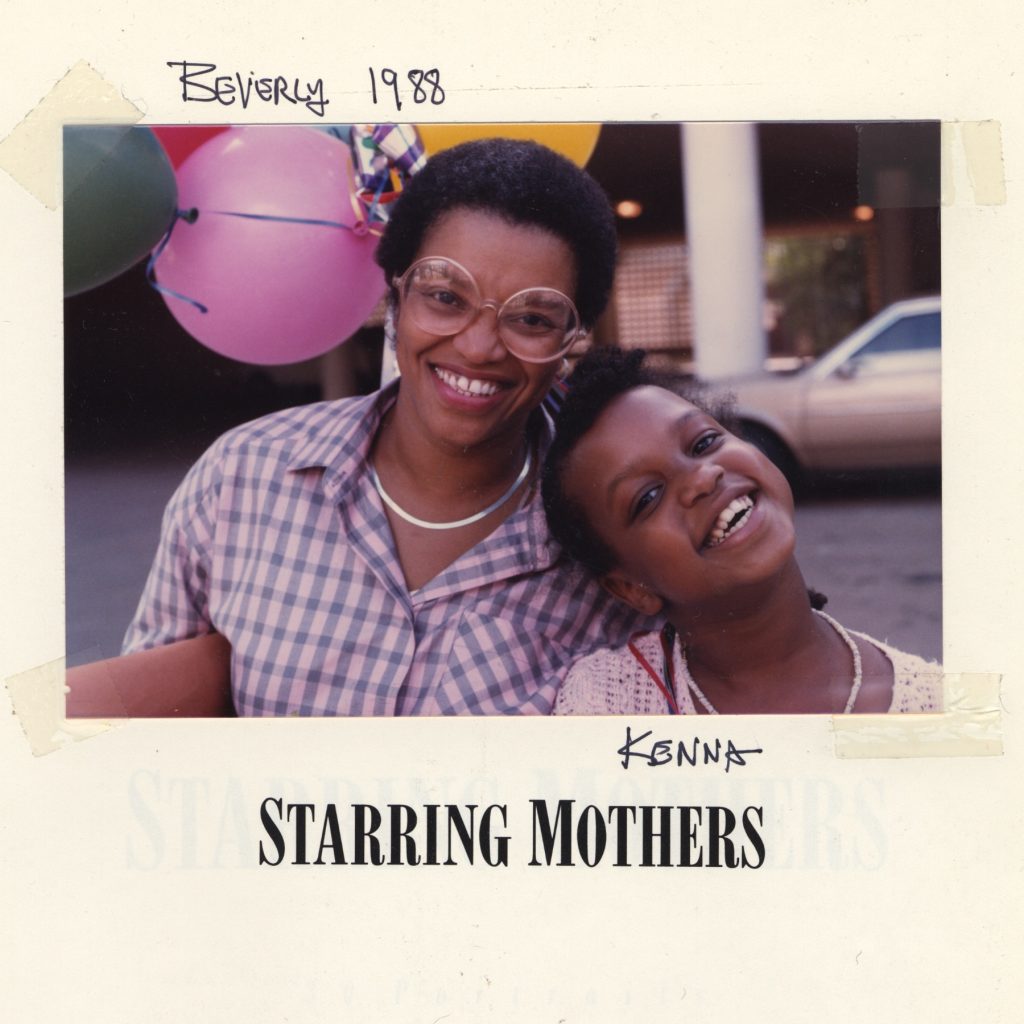

When my mother was born in 1973, the Cottmans became what we Minneapolitans know as Southsiders. My mom Kenna—named after my grandparent’s good friend Kenneth—grew up in a house on Blaisdell Avenue off 42nd St. She attended Park Ave Church on 34th St, and frequently enjoyed breakfast at Currans diner on Nicollet and 42nd. She was enrolled at Lake Country Montessori on 38th and Pleasant; a private school where she—and later I—would learn French, write in cursive, and receive in-depth instruction in art, music, and theater. We were one of few Black children enrolled in our classes.

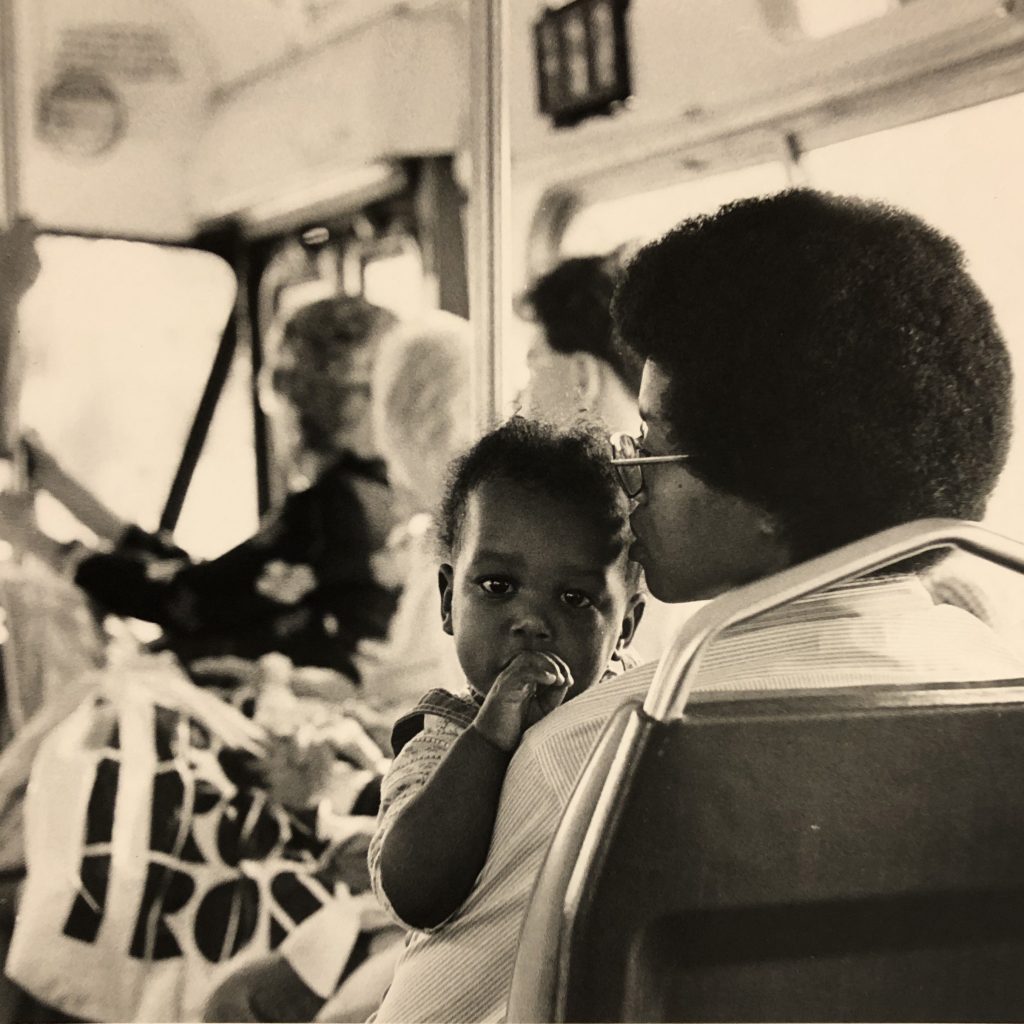

At some point in the early 70s my grandfather encountered The Sweet Flypaper of Life. The Sweet Flypaper of Life is a book of poems published in 1955 by Langston Hughes, interspersed with photographs by Roy DeCarava. “Black people taking photos of Black people…ordinary people in Harlem, going about their daily [lives].” My grandfather’s perspective was forever changed. Photography was no longer just the strict, painterly compositions he had been making, insisted upon by the camera club. His intimate and candid shots of family and everyday-life, stored in boxes in the basement, were works of art.

Their value existed not in their form but in the subject(s) of their frames(s). He sought the work of other Black photographers, like James VanDerZee, and Gordon Parks, who had lived in Minnesota. In 1976, he landed a spot in the short-lived Black Photographers Annual, a publication compiled by Black artists in New York, and which exhibited in Harlem, D.C., and Moscow. In Minneapolis, he began teaching “Intro to Photography” at YMCAs and “Darkroom Techniques” at the Martin Luther King Center in St. Paul.

In 1982, my grandmother was shuffled by the school district and transferred to North High School, mascotted by the Polars. The family also moved to a new house in Bloomington, further south than the Kingfield neighborhood they’d previously inhabited. Again, my grandma knew no one, but she had been teaching for a decade, and was inspired by North High’s dynamic and engaged students and staff. In 1989, my mother enrolled at North, and joined my grandmother on her daily commute to the thriving campus. North High bordered North Commons Park, and an abundant Black community in the surrounding neighborhood. In contrast to the mostly white Southside, North High was a welcomed cultural shock and breath of fresh air for my mom. She jumped headfirst into dance classes, cheerleading, and Polar Pride. My grandmother would teach biology at North High, and for the next twenty years cement her legacy as an educator, creating an irrevocable impact on the lives of thousands.

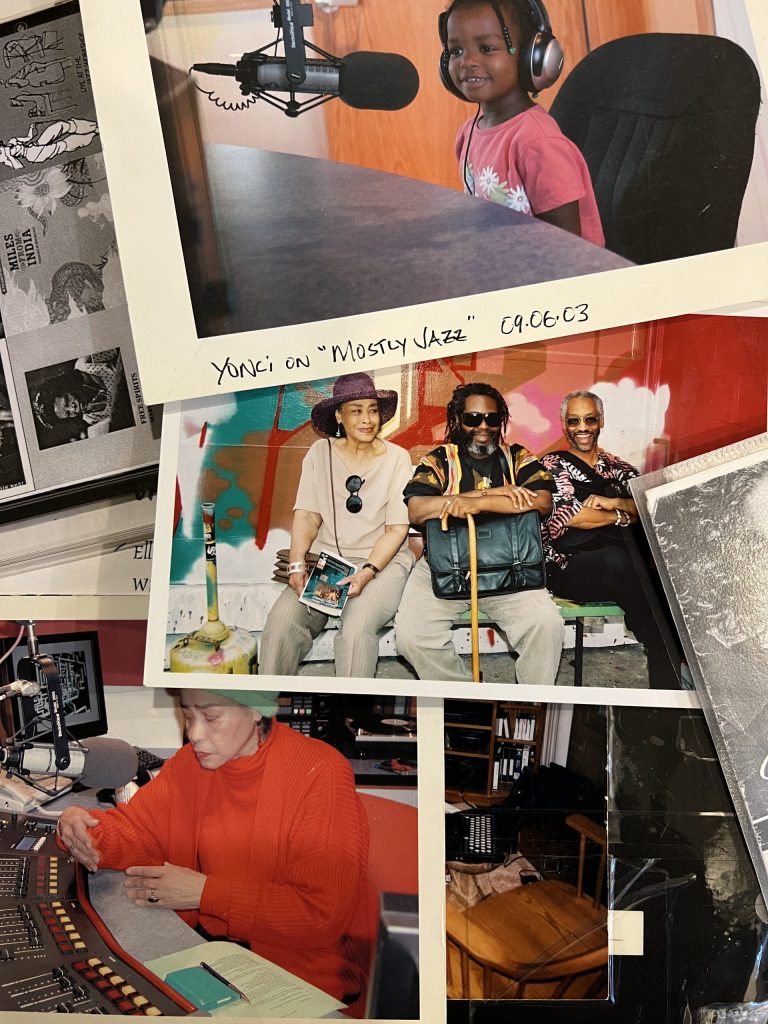

Though their feet were on the ground over North, the Cottmans still had Southside roots. On 36th St. and 4th, my great-grandmother Patricia Walton, lived across the street from Hosmer Library. As the host of “Mostly Jazz” at KFAI Radio on the West Bank, my Nana always had an ear out for new music. Her closet was full of fabulous clothes and library was filled with jazz records. Jazz pianist Cedar Walton was said to be her cousin, so she was always in the know about what was cool and who was coming to town. When musicians pulled up for shows at the Dakota Jazz club in downtown Minneapolis, she would ask Cousin Cedar to put her on with the players, so she could get them to record for her radio program. Branford Marsalis, Ernestine Anderson, McCoy Tyner, and more endorsed her show.

In the mid 90s, my grandfather became curious about his mother-in-law’s technical prowess in running her radio show. After he hung around the studio a few times while my Nana went live, he began researching some of the music being played and gradually picked up running the broadcast board. On Saturday mornings, they’d spin Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, and Sarah Vaughan. At the same time, they’d offer historical facts on the artists, muse about the culture of appropriation in the jazz music scene, and collect station I.Ds, from Ahmad Jamal, Ravi Coltrane, Rene Marie, and more.

In 1997 an opportunity presented itself: a trip to Ghana. During the trip the Cottmans would spend a month with three different families in Accra, Kumasi, and Cape Coast. They immersed themselves in the culture and traditions of West Africa. Within six months of their arrival back in the states, my grandfather accepted an early retirement offer after an extremely successful twenty-one years managing Home Security sales at Honeywell. In 2002, my grandmother would retire from North High biology. Both would fully turn to their artistic vocations.

Their story has been told numerous times, to numerous people. When writing it, there is very little mystery. I never sensed doubt in their retellings, or heard any lingering “what ifs”. Their story was picturesque, it was a story they affirmed time and time again. They endured. Every option was meticulously weighed, every decision methodically made, and every action dutifully fulfilled. My grandmother was as strict and firm an educator as she was a mother, my grandfather as precise and detailed an engineer as he was a father. My mother had a good childhood, yet her independence was often stifled by my grandparents: they determined what clothes she could wear, what media she could consume, and where and when she could spend her free time.

Whatever idea they dreamed up about who they wanted my mom to be was fractured after her expulsion from a notable southern HBCU for smoking weed in the dorm; a testament to her newfound freedom. Her return to Minnesota was unabashed; she had been invigorated by the loud & proud Blackness of the South that North High had prepared her to embrace, but that lacked a signifcant presence in Minnesota. She finished her BA at Normandale community college, and transferred to the University of Minnesota to earn a MA in Elementary Education; following in my grandmother’s footsteps. At the University of Minnesota, she joined the Africana Student Cultural Center; and with her peers, hosted events and curated shows, and savored the ripening scene of 90s hip-hop.

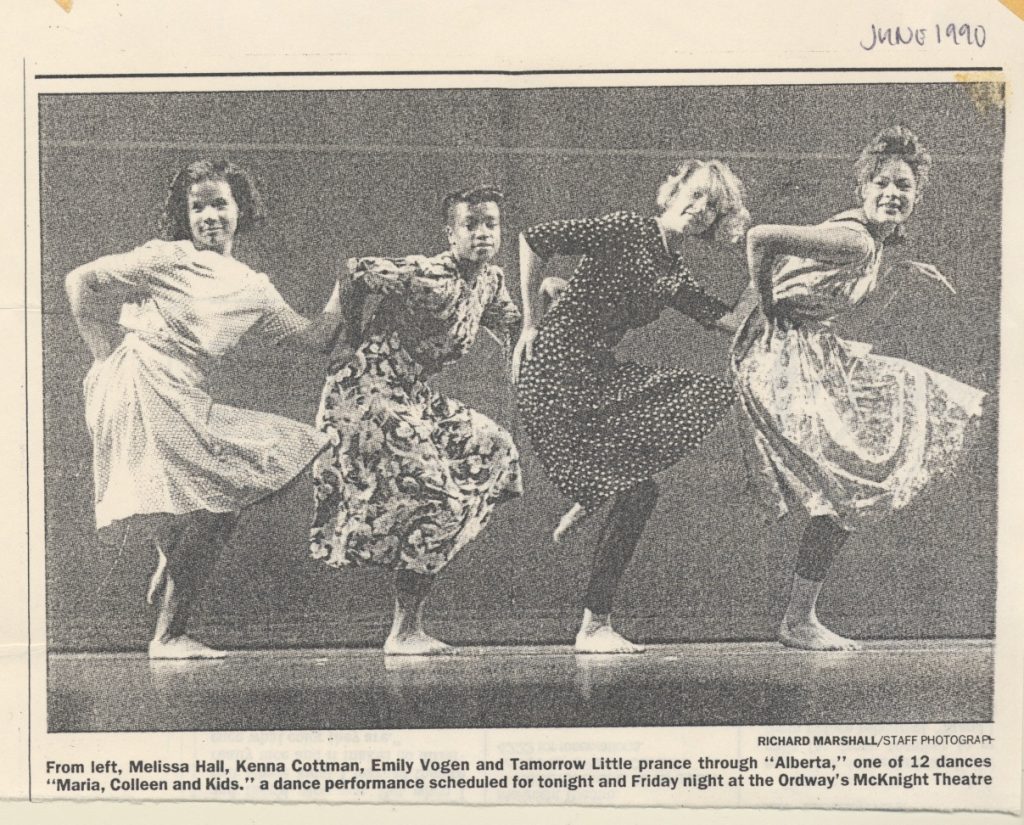

My mother was inspired by the Afrocentricity in the 90s of Black America and through dance, adopted the cultural traditions of the diaspora as her own. It was here, at the intersection of Black American practices and traditional African culture, where my mother’s identity as an artist flourished. She joined a Liberian dance group headed by Nimley Napla, took classes from Patricia Brown at Patrick’s Cabaret and Morris Johnson at Jawahiir’s studio, above the Burch Pharmacy on Hennepin and Franklin. A trip to the National Black Arts festival in Atlanta left my mom in awe of an all-women’s ensemble who performed traditional Senegalese Sabar. She came face to face with a primary source—master Youssouf Koumbassa of Guinea, accompanied by Babacar M’Baye—at a dance conference, where she was floored by his teaching. During my mom’s attempts to phonetically transcribe rhythms and write down dance moves, she came to the realization that what she was learning in Minnesota was not the real thing, but rather the interpretations of Black American choreographers, the synthesis of past knowledge within contemporary form.

Back in Minneapolis, she joined another African dance company, practicing out of the Minnesota International Drum center on Lyndale. She established her own group, Black Pearl, made up of friends from college and high school. They rehearsed in Zenon’s studios at the Hennepin Center for the Arts downtown, and performed a block away at First Ave and 7th Street Entry. At Patrick’s on Minnehaha and Lake, she was one of few Black performers on the bill at the weekly cabaret, and at Intermedia Arts on 28th and Lyndale she was one of many at her self-curated Black Choreographers’ series.

In the early part of her pregnancy with me, my mom worked at the Electric Fetus, a record store on Franklin and 4th; she was behind the counter in the headshop section. Despite finding her footing in Minneapolis, my grandparents were displeased with her predicament as an unmarried, Black mother-to-be. In 1998, my grandparents rehabbed a deteriorating house in the Homewood neighborhood of North Minneapolis. That house is where I would spend the first year of my life before my mom purchased a home with the same house number, visible from my grandparent’s front stoop, one block west of them.

********************************************

My story starts on the fridge, in one of dozens of photos. We are on the Northside of the city, at 12th and Thomas, in what is now known as Lorraine B. Smaller park, on my grandmother’s knee, with cupcake frosting smeared on my face. It is my birthday party, and grandma—affectionately known to the community as Auntie Beverly—has just told the story of Salif the Tailor to the children sitting at her feet. The story itself is simple: Salif is a tailor operating out of the Sandaga market in Dakar, stitching together traditional clothing for his customers, while weaving a tale of West Africa through the colors of his fabrics. “Blue as the African sky, with white puffy clouds, and yellow as the BLAZING African sun!” My grandmother instructs her listeners to punctate each color with a corresponding hand movement, they repeat the colors and their descriptions in unison. Salif the Tailor is one of a thousand stories she tells, and I am just one of thousands of people she will tell it to.

In the basement boiler room-turned-workshop she assembles ribbons, raffia, bells, shells, glitter and paint, cutouts and collages. These are bookmarks, gifted to me at any occasion. Dog-earing the page of the book is in bad taste, but writing in the margins is acceptable. She embosses her books, so that there is no mistake that the ones I’ve borrowed are “From the Library of Beverly Cottman.” In her library I find paperbacks, hard covers, first editions, hand and textbooks, signed copies. Sassafrass/Cypress/Indigo, In Search of Our Mothers Gardens, Song of Solomon, and krik! krak! are the classics here. When I get an embosser for a birthday present, my collection of books also becomes a library.

I bring my school reading lists to her first and see if her catalog contains any of the assigned literature. She is the first to see my middle school diorama presentation on Mary McLeod Bethune, and her red pen edits are first on my essays, before the teacher. She completes the crossword puzzles from both the New York Times paper and the New Yorker Magazine, keeping each one to reference for future answers. When I am young, I test her on Isaac Asimov’s Super Quiz from the Star Tribune. She knows everything, almost every time.

My grandmother never fully retires. She is on the roster of teaching artists at COMPAS Arts; traveling to schools across the state of Minnesota to tell stories, teach poetry, and instruct students in other literary enrichment. She leads libations at events around town—inviting the audience to speak the names of collective ancestors at the opening of events. Each year she teaches families the Nguzo Saba (7 principles) of Kwanzaa at Sumner Library—the one with the Sudduth collection of African American literature on Olson Highway and Van White Memorial Drive. I am her assistant for these workshops, helping attendees make mkeka’s, traditional mats accompanying the kinara (candle holder) and zawadi (gifts) of a DIY Kwanzaa set up.

Grandma is a life member of the National Association of Black Storytellers, an esteemed member of the Brother Blue Circle of Elders, and a pillar of the Minnesota Black Storytellers Alliance. She will gather with Mother Zulu and Baba Vuzi to host Signifyin’ & Testifyin’, the annual 3-day storytelling festival, featuring a Liar’s Contest, and boasting names like Toni Simmons and Gran’Daddy Junebug. I will watch from the wings and/or fall asleep in the audience at the Central Library, to the trickster tales of Anansi The Spider and Bre’r Rabbit.

Audre Lorde writes my grandma a poem. Octavia Butler signs her copy of Parable of the Talents, to me. She has conversed with Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. Her prints from Highpoint Center are mounted in the dining room, and colorful silk-button-thread sculptures hang in the basement. Her shelves are lined with labeled shoeboxes, and her closet is filled with fabulous clothes. She emails me NYT articles, interviews and essays, and multiple DM’s containing unsolicited advice on using curse words in my erratic tween Facebook posts. “You never know who could be watching,” she presciently says, years before digital receipts and cancel culture discourse become things.

My mom has fully emerged as a dancer, a teacher, and choreographer. I have emerged as a curious nuisance, running through legs during dance classes at Pillsbury House on Chicago Ave, and Jawahiir above the Burch Pharmacy on Hennepin and Franklin.

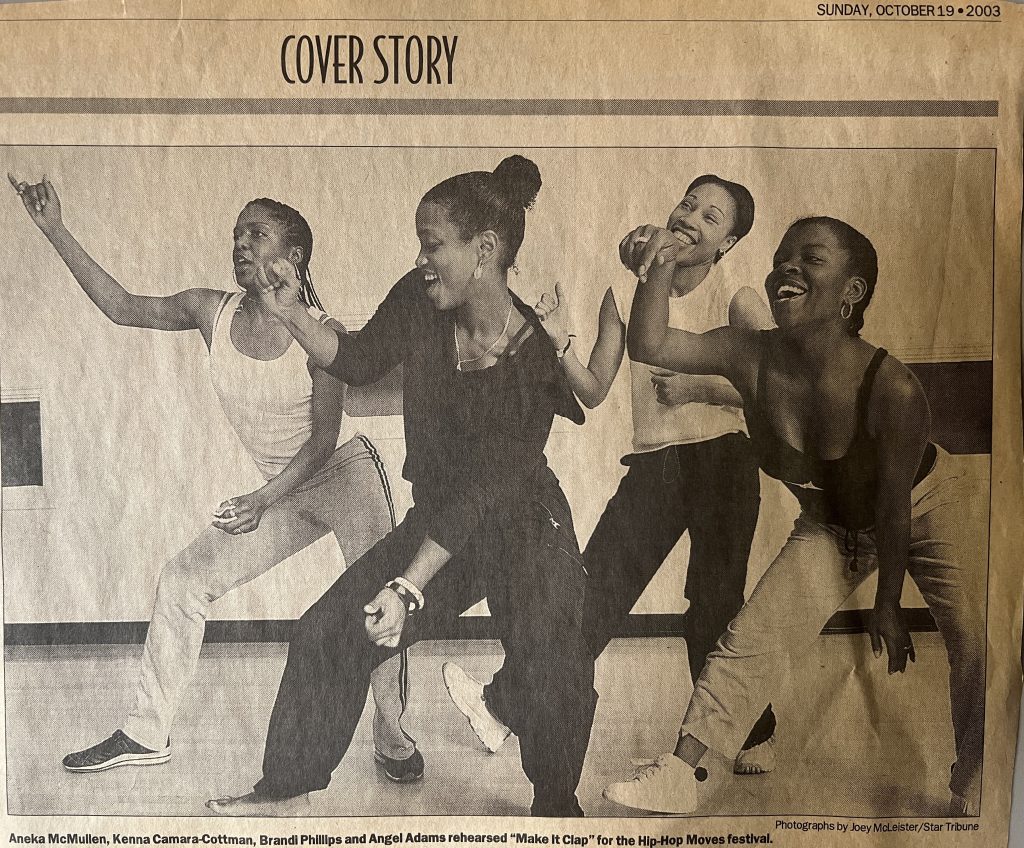

I mess around in the dressing room and try to open locked doors at the Barker Center while she teaches Hip Hop and African to UMN students getting their BFAs in dance. I read YA fiction from the library in the wings of the Southern on Washington while she rehearses with Ananya Dance Theater. In 2008, my mom establishes Voice of Culture: “West African drum and dance with a Black American twist,” made up of a rotating community of former students, peers, and any Black folk looking to deepen their knowledge and practice of diasporic arts. My first time picking up the drumsticks is at the People’s Center, before it is a clinic, on Riverside Ave. Now I can no longer play in the shadows, now I must perform.

We get our drums and attire directly from Guinea, orchestrated via connections my mom has made in the African dance community around the country. VOC practices in the basement of Homewood Studios art gallery on Plymouth Ave, in a visual arts studio on the 2nd floor of 1108 W. Broadway at Juxtaposition Arts, and on the 3rd floor of Robert’s Shoes on Chicago and Lake at Yoji Senna’s Afro-Brazilian Capoeira Studio, later known as Liquorice Beach. We perform at Midtown Global Market’s annual Kwanzaa celebration at the Minnesota History Museum for Black History Month, and at Theodore Wirth Park’s Juneteenth festival. I am deft enough at the douns to join the “grown folks” gigs, playing night shows at First Avenue, the Varsity Theater, and Icehouse. Yet I am a begrudging participant in many of these performances. Where I’ve been afforded self-determination in my hobbies elsewhere, I am forced to sing, dance, and drum my culture with no choice. My mom and I argue often about my attitude. My grandma tells me to smile on stage more. I’d rather be reading.

Later, on a trip to Banjul, in the Gambia, my mom meets Pajack. A year later she returns to be engaged with his family’s blessing. Pajack migrates to the United States, landing in Minneapolis’ January winter, where he gets into bed wearing boots and a winter jacket on his first night in town. After eight years as an only child, my brother Ebrima is born in 2007. Alongside a love of Legos, video games, and soccer, he too excels at drumming djembe, and will also become another unwilling participant in my mother’s endeavors.

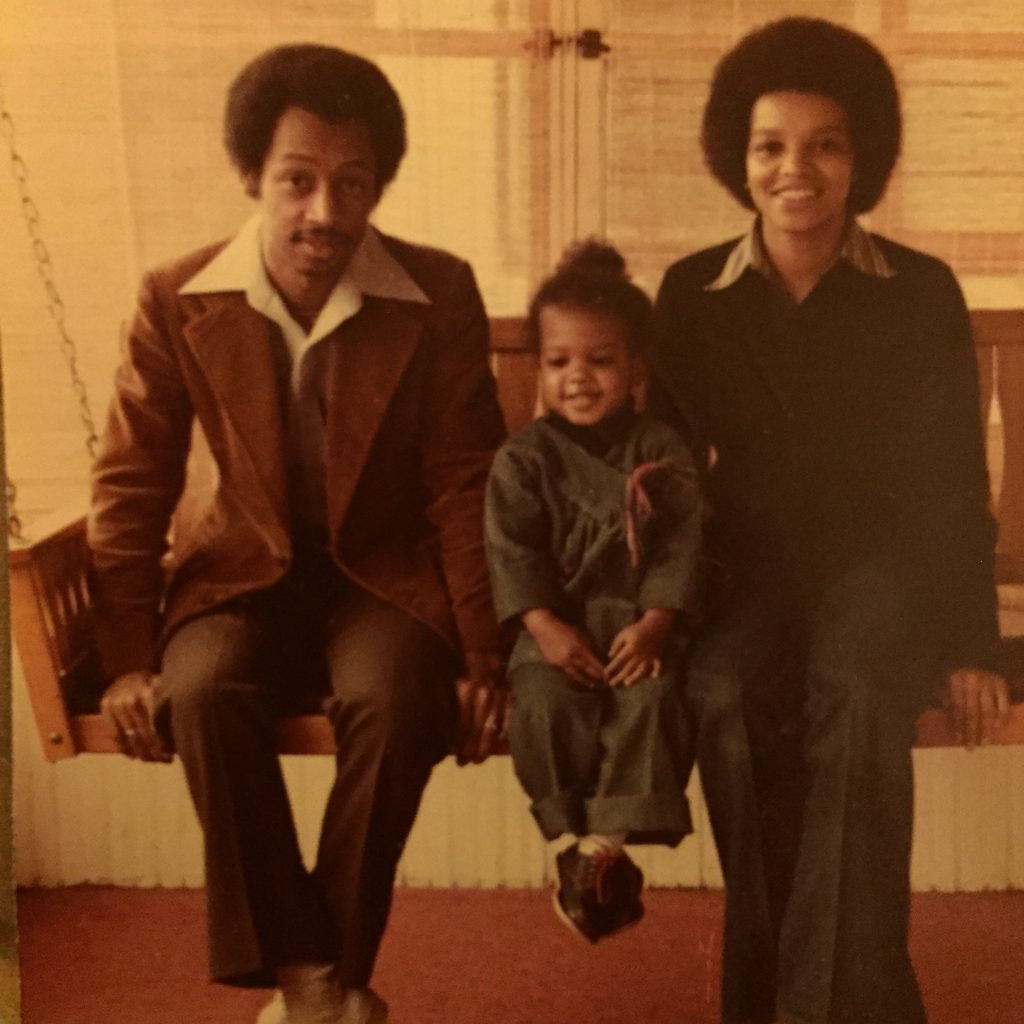

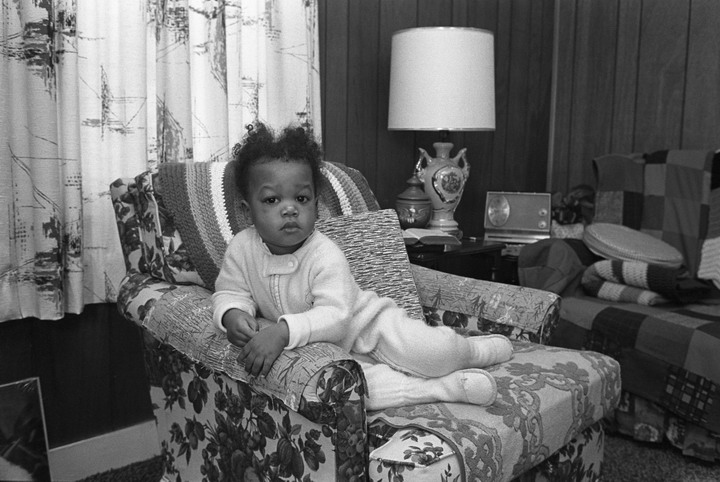

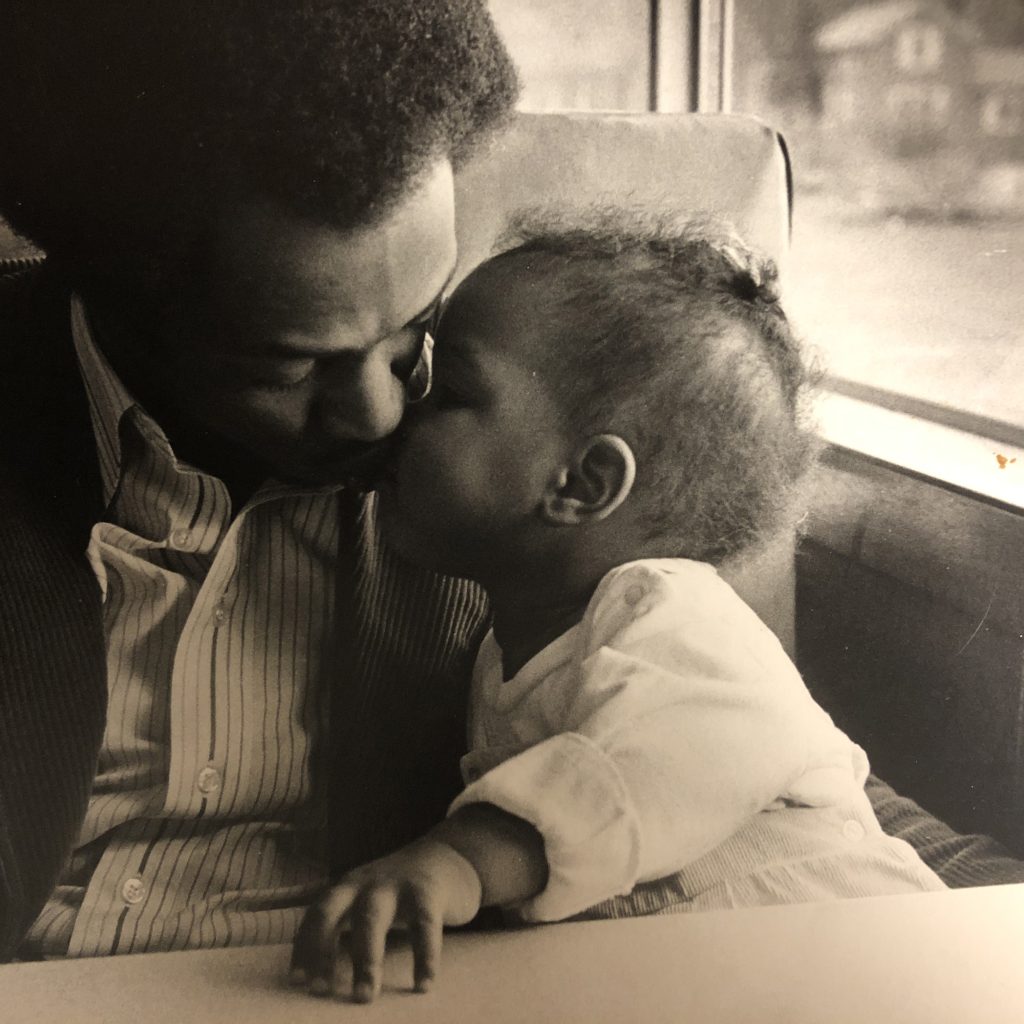

After dinners at Grandma and Grandpa’s house, I ask to be excused so I can retrieve a photo album, picked randomly from the five to seven unmarked, three-ringed binders on the bookshelf behind grandpa’s desk. Sometimes the photos are of me, a smiling baby, reading with grandma as a toddler, or on an excursion with grandpa as a little kid. Sometimes the photos are of my mom: posed with my grandparents who sport matching afros and vintage denim, or in her North High cheerleading outfit. Sometimes my grandparents cannot decipher who’s who in the photos; whether it’s me or my mom. My grandfather has documented us all from birth, my mother, my brother, and I.

As our lives have developed, we have always been his landscape to capture.

In the basement darkroom, there are boxes upon boxes of film negatives. Here, he has stored the physical negatives, before the technology that allowed him to digitize his archive was developed. His older photos are more formal, family portraits and profiles in black and white. His more recent work focuses on the candid and casual. These “social landscapes” nicely pair with the advent of social media. He is impressed with Steve Jobs and amazed at the capabilities of smartphone cameras. Facebook becomes his digital diary. He posts photos of his coffee from Mayday cafe on 35th and Bloomington, and blueberry muffin from Hard Times on Cedar/Riverside; book and film recommendations, and his musings. When he gets his short Wally Blues (famous and homegrown blueberry walnut pancakes) from Al’s Breakfast on 14th in Dinkytown, he shows the staff the photos he has of our family with the Al. The most harrowing of my fashion choices as a closeted queer youth are documented in the photos he’s taken of me: I’m with his foster father, Mr. Hawkins after church at Park Ave in one, playing my clarinet recitals at Walker West Music Academy on Selby in St. Paul in others, and sharing meals in others still. I think I am supposed to ignore him when he takes photos of me, but as an increasingly self-aware teenager, it becomes impossible. The subject takes on a life of its own.

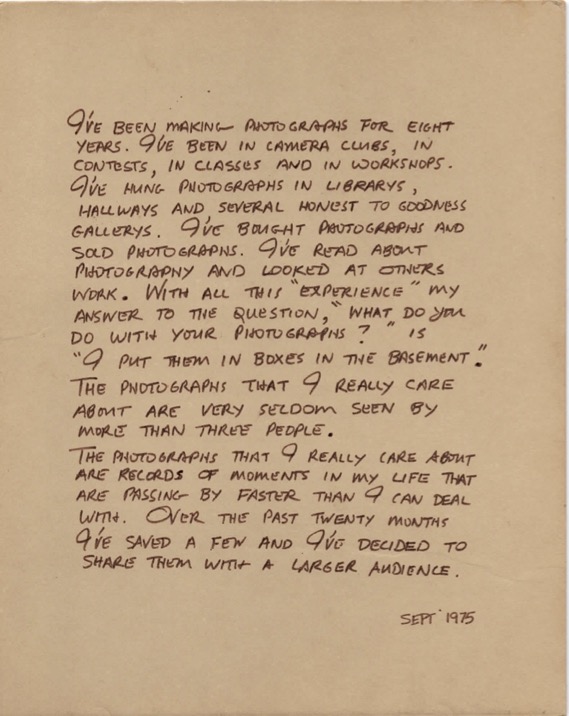

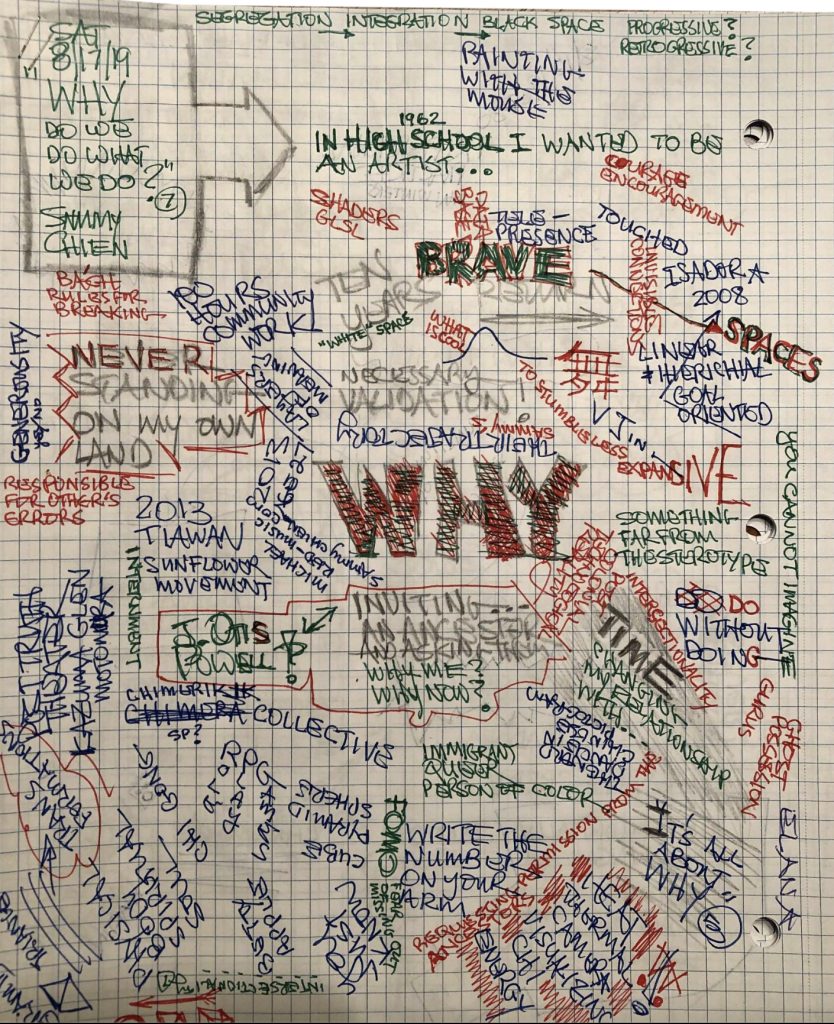

My grandfather is also a journalist: he has written in a journal almost every day for 18 years. His journals are lined up in a row at the head of the work desk. Always Moleskine, 3.5 x 5.5 inches, black, sometimes red, numbered and dated on the spine. #1 starts in September 2006, “Carry this with me always.” is written on the first page. “Always” is underlined. His penmanship is bold, full of capitals. Each page is etched with his words, tactile, like braille. We are the only lefties in the family. My writing smears, his somehow, does not. His entries range from mundane—musings on events of the day, first-world complaints, recaps of conversations, ledgers of health updates—to profound—grievances and critiques, elegiac self-reflections—to the cryptic and artistic—chaotically organized charts and lists, outlines of tech specs and projection dimensions, all indecipherable to anyone but him. The family is referred to by their initials. He is BC1, my grandma BC2. I am YPJ, my mother KJC, and my brother EBS.

My grandfather writes poetry too, in his journals. He has been influenced by:

“Romare Bearden’s collage technique, Dean Kessmann’s plastics on paper, Roy DeCarava’s photographs, Duane Michals’ photo-sequences with text, Ben Shahn’s text-image social realism, Richard Wright’s Haiku, Langston Hughes’ poetry, Frederick Sommer’s cameraless abstractions, and the life and music of John Coltrane.”

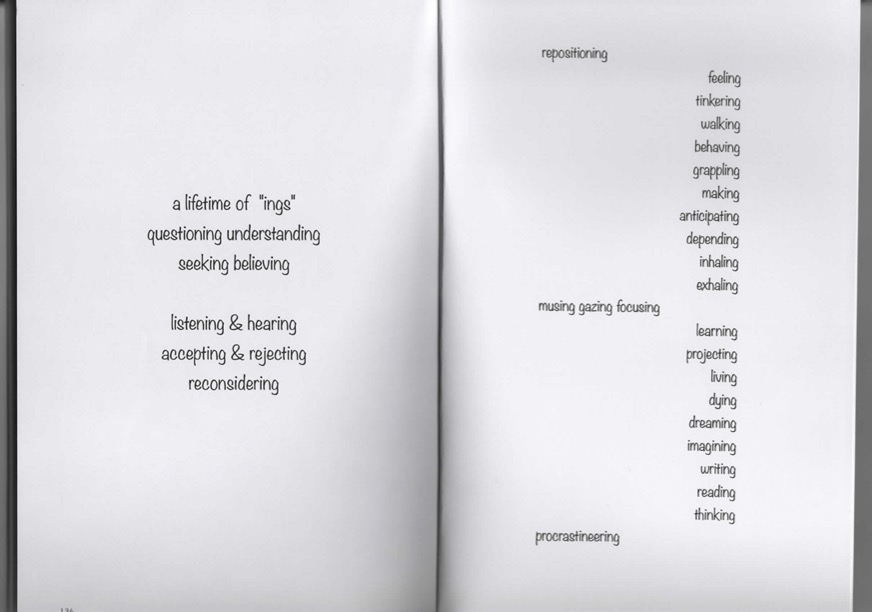

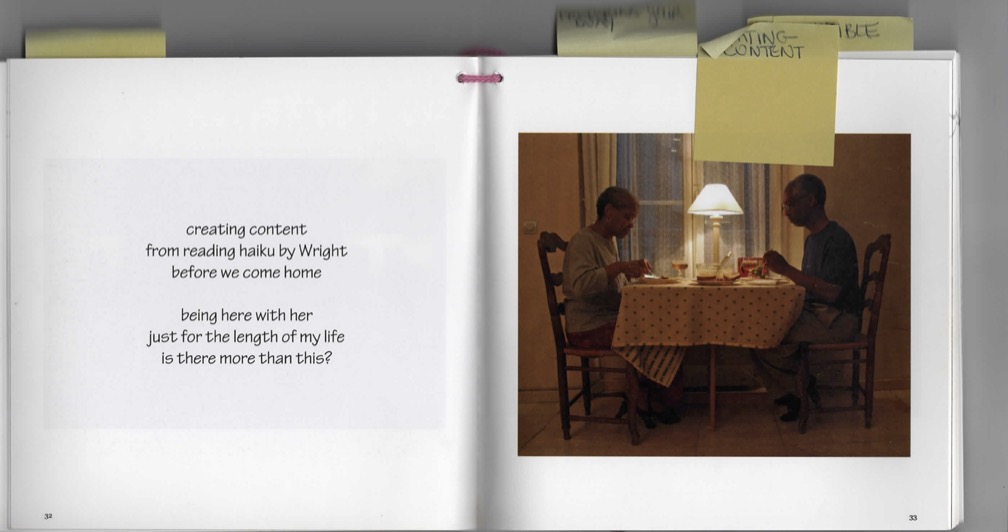

He writes Senryu, calling the form by the sum of its syllables. His “seventeens” address the “simultaneous nature of living and dying.” He shares his 5-7-5’s with friends and family via email, texts, and Facebook posts, eventually publishing Surface Tensions, Disturbances, and Presence, books of Senryu accompanied by photographs.

He forms The Ways Ensemble, with my grandmother, my mom and his good friend, backgammon opponent and collaborator, J. Otis Powell‽. Their performances embody a theatrical jazz aesthetic and range from “stories from the past, allusions to the present, and disturbances to the future,” in a synthesis of projected images, choreography, spoken word poetry and soundtrack(s). At the Old Arizona and Pangaea World Theaters, I am in the audience. Sometimes my image is projected, or my name is spoken, and as an adolescent, I balk. I am distinctly aware of my presence within these performances, but only later will I be fully realized.

From January to March, my grandparents leave Minneapolis for a yearly “sabbatical”. In Puerto Morelos, Paris, Barcelona, Singapore, Thailand and Brazil, my grandpa shares images of food, scenery, street art, and people, mostly my grandmother. Often, he shares images of his immediate surroundings: a tableau of coffee, pastry, and his journal, at a table somewhere, in view of passersby.

I get my own sabbaticals, in the form of spring break trips orchestrated by grandma. Before AirBnB, we stay at real bed and breakfasts, where the rooms are themed, and breakfast is prepared and shared with the other guests in the mornings. My first time on the Amtrak train is to Chicago, where we visit the Bean, eat at Italian Village, and I learn who Jean Baptiste Point duSable is in the city’s history. In D.C., we tour the National Mall and visit the Smithsonian. In New York, we stay in Brooklyn, eat in Harlem, and see Fela the musical on Broadway. My grandfather books us sleeping cars on the two-day trips to New Orleans, and to Seattle on the Empire Builder. My grandma takes us aboard the Holland America cruise line, sailing between the Caribbean islands. In high school she flies us to San Francisco, where we see Wayne Shorter in concert, and my grandfather’s photo amongst thousands in an exhibit at the Museum of the African Diaspora.

Each spring break trip has an itinerary, handwritten on a yellow legal pad, curated by my grandma. Besides recognizable landmarks and tourist attractions, everything we do is decided by her. I am still expected to do my homework. Before Uber and Lyft, we use physical maps, and get to our destinations by bus, train, or on foot. A taxi is called only in the most extenuating of circumstances. Our last trip is my junior year in high school, to Paris, where my grandparents have been numerous times to revel in the history and hedonism of Black American artists in Europe. We stay in Marais, visit the Picasso museum, the Musee de Quai-Branly, while my grandpa attempts to get us to see a David Murray show at a nearby jazz club. We eat Senegalese food, frog legs, and a cafe au lait that changes me irrevocably. We take the Metro, visit the flea market at Porte De Clignancourt, and walk along the Seine. One night, I sneak out to buy cigarettes, to impress my friends at home. We do not ascend the Eiffel Tower, but view it from underneath, and around. Just the two of us together, witnessing, is enough.

********************************************

When my grandfather takes his last breath, it is with us, in the sunroom at home on Dec 5th, 2021. He has written out a death directive, which details everything down to the position of the hospital bed in his journal. When my grandmother takes her last breath, it is in a hotel room in Cairo, Egypt, on March 11th, 2023. The 13-day cruise down the Nile was their next planned sabbatical, after two years of not traveling due to the COVID-19 pandemic. My grandfather’s funeral is at Estes, on Plymouth and Penn over North, broadcasted virtually and sparsely attended. My grandmother’s funeral is at the Northside Healing Space, formerly Kwanzaa Church, on Emerson Ave, and attended by hundreds. I sit next to someone who asks me if I am related to Beverly Cottman. In July 2022, when we celebrate my grandfather’s 80th heavenly birthday at Bethune Park—like how he used to do every year—someone asks me how I knew Bill Cottman.

I do not share my grandparents’ last name. I share their features on my face, their chortles, their grimaces and their gazes. I share their pasts and presences.

Now, I share their story. I am still writing mine.

* * *

This fellowship is made possible with support from Arts Midwest. Arts Midwest supports, informs, and celebrates Midwestern creativity. They build community and opportunity across Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin, the Native Nations that share this geography, and beyond. As one of six nonprofit United States Regional Arts Organizations, Arts Midwest works to strengthen local arts and culture efforts in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts, state agencies, private funders, and many others. Learn more at artsmidwest.org.

About the author: Yonci Jameson is a Cultural Curator, DJ, Musician, and Writer born/raised/based in Minneapolis. Yonci’s practice is an intricate exploration, experimentation, and expansion into the past, present and future of Black Queer traditions. With over a decade of experience in traditional West African percussion & jazz instrumentation, radio programming, arts education & community organizing, Yonci employs performance, the pen & page, bread breaking and a love ethic in solidarity with marginalized communities, in efforts to create a future free of anti-Blackness and queerphobia. Yonci first piece melds memoir, first-person narrative, and an expansive sense of history to tell the story of the Cottman family; whose legacy as artists and educators spans over fifty years in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and whose impact is profoundly present to this day.