With its being consistently called the “crossroads of America” and its capitol lying at the convergence of a series of interstate highways, it might be easy for one to believe that Indiana encapsulates the essence of the nation. Yet, in a recent exhibition at the Harrison Center, a community-oriented arts organization that operates out of a 65,000-square-foot, three-story building in the Old Northside Historic District of Indianapolis, Ethiopian artist Yeabsera Tabb has shown that American interconnection is much more elusive than people let on.

Born in Addis Ababa, Tabb immigrated to America as a teenager, witnessing directly the clashing of very distinct cultures and core beliefs. By growing up in the midst of this experience, she has realized the complexity of what she has termed the “twofold nature of place.” Noting that the concept can be both the environment one inhabits, as well as the mental disposition one has, she has found that “when you experience immigration or migration that sense of place is destroyed to some degree.” That, in leaving one’s home one shall be leaving a part of one’s mind as well.

Such has certainly been Tabb’s experience. Carried away from the crowded and communal markets where children played soccer in the streets, she has found herself in what she describes as a “very individualistic culture” here within American society. In a culmination of her recent years work, her solo show Tizita reflected upon this loss of socialization and community.

Tizita, which is often translated as “longing,” “nostalgia,” or even the all-encompassing word, “memory” is of immense importance in Ethiopian culture. Along with being a popular form of music in the country, one that has been enjoyed for generations, conceptually, the word refers to a very personal, almost psychological, concept or experience. It is one wherein the mind views present moments through a sentimental and saddened haze due to the nostalgic nature of them, as one might when going back to their favorite childhood park as an adult on an otherwise warm and comforting day; the thrills of joyful screams and the sounds of running, pattering feet on pavement separated not just by distance but by time, and the place thus fundamentally changed.

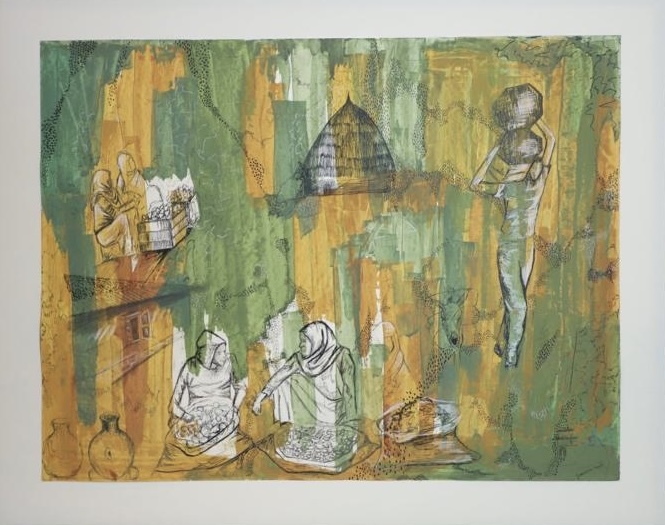

With the notion of tizita at the forefront of her creative process, Tabb explains that her show is “a way of tending to that space in between remembering and forgetting”. That, through her rhythmic watercolors, drawings, and woodcut prints, she has sought to create “pockets of memory”.

Featuring mostly muted and modest colors with stark world’s hidden within them, this personal exhibition is immensely esoteric. The work is intellectually and emotionally approachable, yet—by definition—never fully immersive. Faces, patterns, and places make up its contents, and its histories are comprised of both public and private, highlighting a specific culture but also one person’s particular place within it by detailing Tabb’s engagement with Ethiopian and American life. It is such that it encapsulates personhood as well as place, making quite clear the intricacy and intertwined nature of both. Though, in this sense emotional and metaphoric, Tabb’s exhibition does not ignore the technical.

For where contemporary black art is primarily involved in matters of identity, Tabb elaborates upon a more subtle design using obstructed effigies and the outright non-figurative to further focus formalism. Made most evident in the abstracted and dense surfaces of her woodblock prints, such as the ones featured here, Tabb shows that expression need not be tied to an individual. As she makes evident, art itself can be expressive of both emotions and concepts devoid of direct attribution by an artist or their background.

Nevertheless, with her subject ever intangible, her intentionality is made all the more important. This is something she clearly knows quite well. Her blues are sunken mirrors, her dashes, glances—configurations and compositions all used to capture culture—while cyclically producing it by manner of their own existence and autonomy.

The emphasis she places upon visual expansiveness is itself an important usage of form, alluding to physical area and what can be done with it by manner of a meticulous selection of aesthetic elements and personal choices. For her art does not lie in simply creating the works upon the walls, but in containing them. Her guiding of space in her pieces, both internally in the instances of intentional form and color, and externally, in the boundaries of said works, further elucidates meaning by manner of material. With certain pieces crumbled up at random there arises not only the feeling of the destruction of place and corruption of an otherwise calm continuity—the feeling that a sort of sacrilegious act has occurred—but also the positioning of the viewer as complicit in such abhorrent actions. Through giving her works this vitality, Tabb turns gallery visitors into voiceless witnesses, as so many are, never fully knowing of the destruction of the things around them yet being ever affected all the same. Devoid of frames, these works imply injury, being visibly changed and at odds with her more distinct, enclosed evocations. They convey the concept of tizita in a minute manner by elaborating upon the subtle sorrows and pains brought about by change, all the while showing the fluidity of all of Tabb’s work—specific points and protrusions within the wider duration of time.

Though figurative work is certainly important, Tabb’s creations make evident the specific abilities one can utilize to cultivate understanding when engaged in abstraction. For though there is a great deal separating Americans and Ethiopians, Tabb manages to inform her audiences in the most intuitive and efficient way possible. She does this, not by simply telling them and letting them understand by manner of approximation, or—worse yet—have their ignorance or biases blind them from comprehending, but by immersing them in the very experiences she is recounting. For, at least in part, even the most ignorant and insensitive of onlookers is positioned in such a way as to be readily sidestepping a great degree of prejudice as they find themselves engaged with the indisputable nature of materials as opposed the more intangible realm of meaning. Principally, Tabb accomplishes this feat through focusing upon formalist qualities, by intricately arranging the elements that her creations are composed of. By engaging with her art and audience in this manner she not only pushes against people’s prejudices, but also against conventional modes of utilization pertinent to her mediums, and indeed, contemporary presumptions about what it means to be a black artist.

This complexity, however, does not stop her work from elaborating upon a larger narrative. Indeed, Tabb states that, “Art for me is a political language too. Art is a form of advocacy, of self awareness. It has given me a language to communicate my worldview.” In this sentiment she is not alone. For, though primarily known in public society for his ideas surrounding double consciousness and the like, in an oft underrated art lecture, African-American sociologist and activist, W. E. B Du Bois said the same, proclaiming, “all art is propaganda”.

Though this idea surrounding art was expanded upon under the confines of Du Bois’ overarching notion of the “Talented Tenth,” a controversial term viewed as elitist by many that supposed that a group of exceptional and well-to-do black people ought to take it upon themselves to lift up the rest—even at their own detriment—Tabb implements its message with much more respect for multiplicity. Even still, it is clear that she seeks not to shield her pieces from Du Bois’ succinct statement, with political implications being abundant within the exhibition.

For though her exhibition embodies the historical and emotional essence of Ethiopia; its turmoil, tensions, and truths, are present in the entire African diaspora. Visions of the vibrancy and destruction of place can be found within every land where a beautiful and black heart beats, and Tabb makes this authenticity unquestionable.

In describing the prominence of patterns within her work, she states that “there isn’t immediacy about it, it kind of allows the viewer to take a closer look through the layers.” Thus, although some of the patterns can be seen in traditional Ethiopian tattoos, textiles, and the like, others were made far more intuitively, allowing for an individual exploration. Tabb’s opening up of meaning has it such that she depicts not only what she calls an “iconography of cultural significance” surrounding her own experiences, but the cyclical nature of remembering and forgetting, and the perpetuation of hardship across generational lines.

A threatening set of themes, such cycles lie heavy upon all those darkened and daring heads of which the term “Black history” is comprised, indeed the persistence of pain need not be fleshed out in full here when its endurance is exhibited daily. For it is evident that there exists many similarities between Tabb’s displacement and those of other members of the diaspora.

As Forbes-featured Hoosier history lover and tour guide, Sampson Levingston, has explained, it was the emergence of interstates 65 and 70 that saw the destruction of one of the most refined and radiant Black neighborhoods within the state, one which ran along the historic Indiana Avenue in downtown Indianapolis and once saw a third of African-Americans within Indiana call it home.

“You can look on either side and see the neighborhood that was there, it’s not a secret,” says Sampson, who has given hundreds of walking tours of the area. Previously filled with flourishing businesses, restaurants, and homes, Indiana Avenue was a bastion of Black culture. Over 30 jazz clubs once lined its streets attracting the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and Nat King Cole, while allowing for the development and discovery of the musical skills of jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery and other promising players. Yet the avenue did not serve as just a core of cultural events, with business moguls like the first Black female millionaire, Madam C.J. Walker, selecting the site when it came time to set up shop. Ultimately, the presence of herself and other Black business leaders solidified both the commerce and creativity of Indiana Avenue, allowing it to thrive even amidst the harsh intolerance of the times.

Yet now, such success has largely stalled, with the vast majority of the avenue’s jazz clubs and businesses having both been shut down. “It happened in major midwestern cities all across the country” remarks Levingston, describing the areas decline into desolation. For though the Madam Walker Theater and a sprinkling of murals try to tell the tale of such prosperity, the effects of the expansion of the interstate highway system at the expense of the public are glaring. The avenue and its surrounding neighborhood were slashed in two under the guise of such city planning, causing the displacement of over 17,000 people, the destruction of over 8,000 homes, businesses, and buildings, and the condemning of a total of 320 acres.

When walking down Indiana Avenue one can feel the remnants of time—nostalgia tinged by sadness. Even when one is alone there is a consistent accompaniment, an atmosphere of loss, a suspicion of something greater. It is as if one is walking through an old movie set where the cameras have long since stopped rolling.

Separated by interstate 65, Tabb’s work lies but a moment away from this forgotten world, yet even still gives an intimate overview of its origins.

Noting numerous factors as being causes of America’s lack of organic community, what she calls “serendipitous moments of interaction,” she views that, in part, divisive city planning is to blame. Specifically, she finds that, “There’s not a lot of opportunities for people to connect with each other, it’s a very car-centric world that we live in”. In a country facing what has been described as an epidemic of loneliness by the surgeon general, such certainly must be kept in mind. Indeed, for community to mean anything at all it must be accessible to those of which it is comprised.

By no means a new issue, the 19th-century sociologist, diplomat, and philosopher, Alexis de Tocqueville appears to agree, having stated in the second volume of his widely known treatise, “Democracy in America,” that—devoid of community—“civilization itself would be endangered.” As expanded upon by numerous neo-Tocquevillians, most famously that of the political scientist Robert Putnam, such a dire statement is not without importance. Americans are untethered from each other more than ever before, and the growth of harsh suburbanization tactics that diminish the presence of third spaces in rural areas and cities only seem to be making matters worse.

Though primarily elaborating upon Ethiopia’s vibrant and engaging sense of organic community, Tabb believes that “genuine community can happen anywhere in the world,” she simply finds that “the hindrance is infrastructure, the hindrance is the culture of the place”. By engaging in fundamental shifts of how we think about and treat the places that we live in—the environment that influences us—we can create better communities. As succinctly stated by Levingston, “the land is valued, the property is valued, therefore the people are”.

Though Tabb’s work no longer lines the walls of the Harrison Center, its ideas and implications are ever present amidst the intense divisions of our time. She has made it all the more clear that community is at the core of our being and, though art advocacy is by no means new, has begun to speak up about some of our greatest challenges. These surely shall not cease soon, so the question remains: will we have enough solidarity to face them? In her examination of the intersection of tizita, memory, personhood, and place, Tabb shows us we can. For creativity—ever invigorating of the imagination—yields an understanding like no other, connecting people and places beyond the bounds of time itself.

About the author: Caiden Cawthorn is a legally blind writer who seeks to shed a light upon that not readily seen. Born in Indiana, he has consistently contributed ideas and articles surrounding art and culture to the Indianapolis Recorder, the country’s 4th-oldest African American newspaper currently in existence. In addition to this, his interviews, essays, and other works, can be found amidst a host of other media outlets at the local and national levels.