This article was developed and written as part of Muña, an art writing program providing a cohort of six writers the opportunity to critically and creatively engage with art writing strategies, readings, exercises, and conversations. The program is structured for writers to develop and refine their practices through guided workshops and peer-review feedback. Its task is to stir, incubate, and pollinate shared consciousness on holistic, equitable, and attentive art writing and language practices. Muña is a program collaboration by Chuquimarca and Sixty Inches From Center.

Before 18 months of age, infants are generally unable to recognize themselves in a mirror; their reflection has spatial depth and visual presence, but isn’t connected to an inherent “me”-ness. In Western psychology, the arrival of self-awareness is measured by the “mark test,” in which a baby is plopped down in front of a mirror with a colorful post-it affixed to her forehead. If the baby, seeing her own reflection, reaches up and grabs the post-it, that piece of paper transforms into a one-way ticket from the world of the infant to the world of the child, a budding self-consciousness that latches onto predictable routines: school, play, family.

But when do we begin to recognize ourselves in all of our other reflections, the non-irl ones? A good question for Liz Vitlin.

Vitlin’s exhibition at Prairie, Liz’s Childhood Computer: 2003 – 2005 (September 24 – November 6, 2022) is composed of photographs, school assignments, videos, and digital collages made by the artist as an 8-year-old, recovered from the hard drive of her childhood computer. Selected by Vitlin as a grown-up artist, these artworks represent an “engagement with the digital archive of her younger self,” according to the exhibition’s accompanying essay, giving the impression of a collaboration across time. Vitlin, curating and interpreting her childhood artwork, presents a selective portrait of her younger self exploring the virtual “mirror stage,” trying on different costumes, poses, expressions, and mannerisms in the reflection of the personal-computer seeing eye. The images retain just enough peculiarity — the traces of child Liz’s personality, likes, dislikes, and humor — to prevent dissolution into a sociological study of white, middle-class girlhood, and return always back to the uncanny sensation of watching the artist converse with herself.

Think about it for a while and the exhibition begins to recall Being John Malkevich: adult Liz watching little Liz watching… computer Liz. At the heart of this rabbit hole is not the distilled essence of Vitlin’s adult or childhood self, but a third person, as the exhibition essay notes, located in “a computer somewhere in-between.”

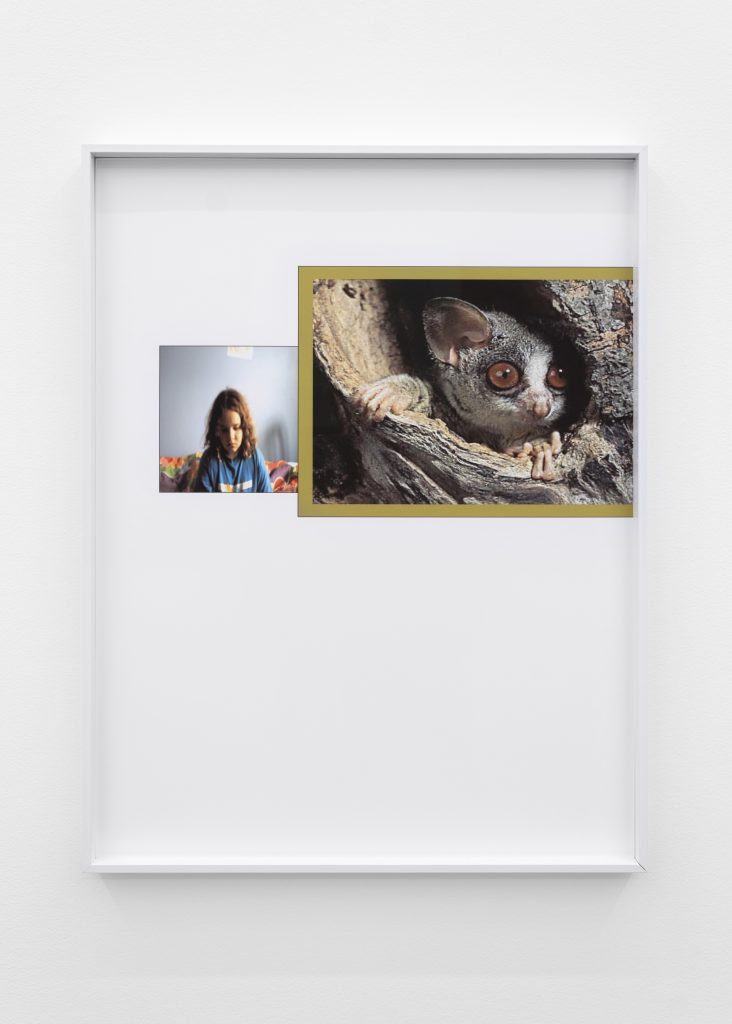

Case in point: Doc5.doc [March 22, 2003], 2002, a Word composition that pairs a self-portrait of a downcast child Liz in a blue and white shirt sitting on a floral bedspread with a large swamp-green rectangle framing a pixelated, wide-eyed bushbaby. The bushbaby furtively peers out of a tree cavity, its amphibian hands grasping the outer edge of the den and supporting an ear so alert that the anticipated next moment, the light speed flee of a small mammal seen or startled, feels already imminent.

The tense bug-like attention of the bushbaby is, at first, contrasted by the gentle Sad Portrait. Child Liz casts her gaze downwards, a perfect introspective pout. Vitlin’s expression, however, has the amateurish, staged quality that all classic, irresistible pouts do — the same way I, in my girlhood, could only hope to look before being scolded and left in time-out, teeing-up the imagined, euphoric moment in which a parent, suddenly overwhelmed by my essential sadness and smallness, would renounce a punishment entirely and forget the terms of my wrongdoing. Vitlin’s gentle frown, relaxed arms, and dejected gaze all seem calibrated to cue this parental response. Her computerized reflection becomes an experiment in seeing and being seen, her self-portrait containing both the bushbaby’s furtive bravery and instinctual fear. Vitlin reflects herself peering out into the world from deep inside her shell, on high alert, sincere and watchful.

The sincerity that Vitlin draws out of her personal archive feels both endearing and painful– leftover from an era of girlhood now gone. We are now all too aware of the harsh effect of computer-life on the images children make of themselves, visible in leaked dossiers detailing upticks in anxiety and depression for girls online as well as the popular perception that young girls look older than they used to (an online tabloid article, for example, titled “Do pre-teens still exist, or did social media wipe them out?”), and the curious biological observation that puberty starts earlier now than it did in the early 2000s. Child Liz’s disarming gaze and adult Liz’s presentation dredge up a well of affect mired in the fleeting privilege of childhood, preserved by durable hard drive memory.

Not all of Vitlin’s images feel so distant. One of the more enduring and elemental childhood experiences stored in Vitlin’s hardmdrive is a fascination with animals. Along with the bushbaby, three of the seven inkjet prints hung around the gallery feature pets or stuffed animals, a live chinchilla and well-loved silver teddy bear posed in a pale yellow scarf and gloves. Though small animals are a recognizable childhood fixation, Vitlin’s photographs appear slightly off-kilter; the teddy bear, for example, is awkwardly propped in a standing position in one photo and about to keel over in the other, silhouetted against a white background by an uncomfortably bright flash. DSC01195.JPG [August 19, 2004], 2022 evokes the 2010s fascination with ‘cursed images’, a gray chinchilla standing on its hind legs reaching up towards a bouquet of red-tinged roses perched on a wood ledge next to a pink bubblegum roll. The bright red timestamp marking the left side of the photograph (could it really have been taken after midnight?) recalls the deep psychic twilight of the childhood pet, a formative platonic attachment and a cruel lesson in the brevity of life.

The exhibition essay diagnoses the strange atmosphere of Vitlin’s images as a symptom of the “uneasy suspicion that they were never intended for our eyes,” productions of a developing mind offloading a mechanical creative impulse. Another uneasy suspicion, perhaps, is that the images did serve some function for the child Liz — the talismanic photograph of a pet, for example, becomes a functional memento mori.

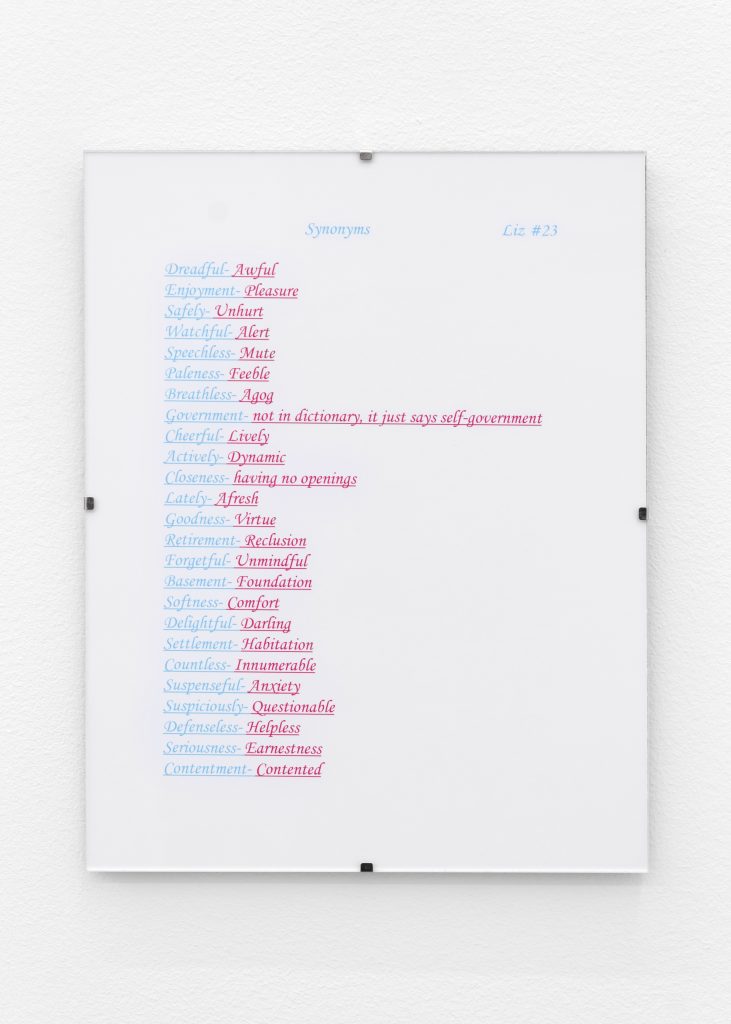

Less morbid, on the other hand, are the works that were meant for some eyes, if not ours. The exhibition includes the school assignment Synonyms #1.doc [February 24, 2005], 2022, a two-columned list of 25 pairs of synonyms in light blue and cherry-red. The contrasting colors make the word pairs seem more antonyms than synonyms, disrupting a basic cognitive association between color and language — similar to the Stroop Color and Word Test (familiar to any player of Nintendo’s Brain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day! video game, released in May 2005). Some word pairs are philosophically intriguing (is “goodness” the same as “virtue”?), others evidence of knowledge but not comprehension (“paleness” and “feeble”), evoking yet another assessment: the Turing test, meted out to AI programs at a feverish pace to catch the moment of passage between computer and human comprehension. Descriptions of programs claimed to have passed the Turing Test often turn to anthropomorphic comparisons between advanced AI and human children. Blake Lemoine, a Google Engineer who went viral for claiming that a chatbot had achieved human-like consciousness, noted, “If I didn’t know exactly what it was… I’d think it was a 7-year-old, 8-year-old, kid…” Vitlin’s synonyms gesture towards the function of childhood as a threshold between human and computer, a proxy for technological optimism and anxiety. These big feelings seem empty next to the inimitable inventiveness of young Vitlin’s child mind, her charming curly-cue Lucida Calligraphy font and precocious protest that a synonym for “government” is “not in the dictionary.”

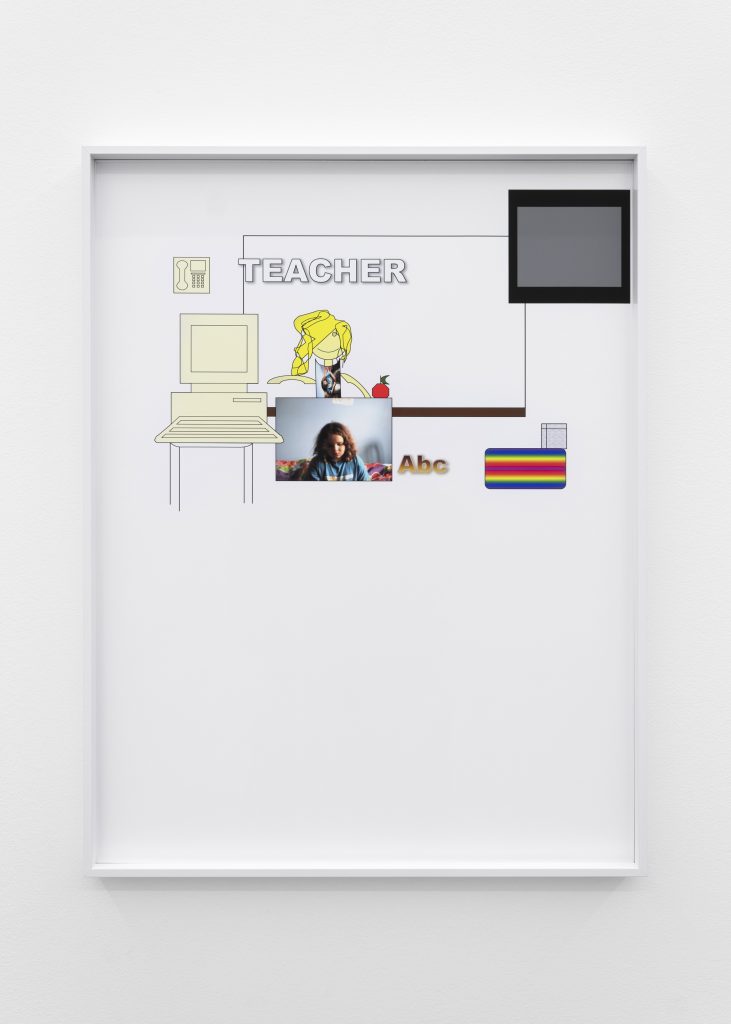

Doc2.doc [March 16, 2003], 2022, a Word picture of an elementary school classroom led by a stick-figure teacher with a messy yellow ponytail and crescent arms. The teacher seems subordinate to a large yellow computer and gray TV screen bracketing her chalkboard, capturing a transitional phase in public education towards screen-based learning such as the advent of typing class and computer lab time (often dominated by early drawing software, like Kid Pix or MS Paint). The Sad Portrait appears again on the teacher’s body and lectern, suggesting a strong attachment to or identification with the teacher and her lectern, crowned with a cartoon apple, absent in the blank computer and TV. Further, it seems, the Sad Portrait has been transformed into a surface, an image fill for Vitlin’s computer world — the externalization of the reflection projected onto the environment, itself a screen to be manipulated.

In the center of the gallery, three Sony CRT monitors play GIF-like videos on loop of Vitlin and friends or family members playing, all filmed with a shaky child’s hand. The videos recall familiar domestic scenes and girlhood activities: sleepovers, dress-up sessions, dance practice. Here, more than anywhere else, the girls seem trapped by the screen, their movement limited, suspended in mid-action. In one of the videos, a girl in a pink crop-top and jeans performs stiff pliés until the recorder drops to the ground, sending the dancer into a washing-machine spiral before she appears again on screen, beginning the routine over. The endless repeating of the scene feels claustrophobic, and the girl’s body is pinned to a screen too small to show her head and feet.

Metaphorically, I see the dancing body’s instability on loop as a harbinger of our age of computer adolescence, in which the computer is no longer a space of childlike play and possibility, but a space of constriction to social norms and regulations— especially in the mass allegiance to ways of presenting ourselves that carry online currency: think the contained, rhythmic choreography of a TikTok dance routine or gen Z and the 0.5 selfie. Vitlin is not the only one to graft onto this phenomenon, and some of the objects on display called to mind certain virtuosos of girlhood and adolescent online despair, Bunny Rogers or Petra Cortright. Vitlin’s childhood images cut close to the quick of image-making online, the irrational mind of the child perfectly suited to reveal the deep unsettled nature of the self through the screen.

More than any of the other works on view, Vitlin’s shivering gifs made me want to log off, touch grass, delete my account; to sit in front of a mirror, put the yellow post-it back on my forehead, and leave it there, forever.

About the Author: Emeline Boehringer is an emerging curator, writer, and art historian. She is currently the Education Coordinator at Wrightwood 659, a non-commercial gallery in Chicago. She has previously held roles at DOCUMENT Gallery, the Smart Museum of Art, and Gallery Sabine in Chicago; CreativeTime in New York City; and the Art Museum at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She studied Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Chicago, and her work has been published in the Bowdoin College Journal of Art. She is interested in slow looking, art and labor, and images as a form of world-making. You can mostly find her cooking, reading, or walking by the lake.