Ever since I spent a winter afternoon in Farah Salem’s studio, the two of us falling deep into conversation, the words of poet Nayyirah Waheed have been whispering in my mind: “Complexity is just simplicity which refuses to be anything else.”

Farah is the kind of transdisciplinary artist whose practice folds in and unfolds out of itself, endlessly and inevitably, as she uses her art and art therapy practices to honor, challenge, and reimagine rituals and psychologies across generations and geographies. If you don’t take the time to fall in, then you’re missing out on a chance to join her in a voyage between worlds. You’re missing an opportunity to expand your understanding of how art moves through our bodies and art’s ability to be a vehicle for ancestral knowledge and the human psyche.

What began as a practice rooted in design and photography has now become something intuitive and precisely untamed. Farah follows her instincts, which has led to her ability to take the tools she’s been given or acquired and use them to create expansive and provoking works through seemingly simple gestures. This can be seen in works like Erode Re-Compose, a series of Polaroid assemblages that, at a glance, look like colorful, collaged landscapes but are, in fact, photographic visualizations of the psychological impacts and distorting effects of trauma on memory. As someone who spends time thinking about memory (re)composition and its relationship to truth and speculative nonfiction, I find form for these ideas within Farah’s work.

The following is a glimpse into parts of hours we spent together discussing her artist origin story, the basis of her artistic ethos, and how the recurring theme of time as material has shown up in her work over the years.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tempestt Hazel (she/her): We’re talking at a transitional time at the edge of a new year. How are you feeling when looking back at the past year and now into the new one?

Farah Salem (she/her): My stomach just flipped — in a bittersweet way. It was such a beautiful year and opportunity to have a studio-focused year at Hyde Park Art Center. I’ve never had a studio space for this long of a time. I grew up making art in my bedroom and never had a designated space. I also never got to do an MFA, I was doing an MA in Art Therapy. You have to apply and be awarded a studio, which is interesting because [students] pay the same. Just because I’m more research-oriented doesn’t mean I don’t have a studio practice. That’s one critique of how institutions work.

I would have a studio for a semester then have to pack up my stuff and go back to working from my apartment. Having this space over the past year really allowed me to unpack and remain unpacked. And to take a look at my work, which has been evolving over the past couple years — even since before moving to Chicago five years ago. My work has always been on the move, folded and unfolded. Now, I’m starting to see the links and am developing better mental bridges for them.

In the coming year, I’m excited about what’s to come [in] one of the projects I’ve been putting off, but finally got to dive into during my residency. I’m getting to a point where [I’m realizing that] this project is going to take me a few years to complete because it’s such a huge research undertaking. I keep finding so much content in it. So, I’m looking forward to multiple years, not just one. I’ll be starting to preview a new project at [Chicago Artists Coalition].

Although I have upcoming cool stuff next year. I’ll be part of a show at [the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP)]. This past year, I really took the time to focus on my studio practice and reduce distractions outside of my studio space. I’ve never gotten to do that, and it’s really special. In the fast-paced capitalistic world we live in, we don’t always get to do that.

TH: I feel like we all are dealing with balancing the immediate with the long-term. We’re trying to give ourselves something more sustainable than the work ethic of capitalism, which often stifles creativity. For you, what has it been like for you to balance the short-term interests and the long-term vision? And sometimes we don’t have answers for that!

FS: To be honest, I think that’s always going to be a work in progress. I’ll go into periods where I think I’ve got the groove of things and know how it works, and at other moments I’m a complete mess. And that’s okay — to be compassionate with ourselves. More than anything, I think it’s about holding myself accountable for these internal boundaries. Like when I book time to go to the studio, then I need to go to the studio. Or if I book time for myself to do [therapy] work — I’m an art therapist and work in private practice doing therapeutic work. Sometimes they blend into each other — as in, ‘I am working too many hours on both per day and I need to better balance them out.’ It’s like a muscle that you need to keep working out.

TH: You mentioned earlier that you used to make art in your room, which sounds like you were talking about the room you grew up in. So, I’m curious about when you first started understanding yourself as an artist or artistic person.

FS: As far [back] as I can remember. I remember when I was 5 or 6, seeing a cartoon of mouse characters having a conversation about what they wanted to be when they grow up. Someone said, “I want to be a doctor.” And I [rolled my eyes] because that’s what my family wanted me to do — to be a doctor or engineer — and I understand where they’re coming from. But then, one of them responds by saying they wanted to be an artist. There was a picture of them painting under a tree or something. I didn’t know that was an option!

TH: It’s always a painter!

FS: I have all these memories of traveling with my coloring pads and craft materials. My mom would always do sewing and fiber projects. Her father was a tailor. She was always working on her sewing machine and would give me knitting and embroidery projects. My hands were always engaged. My dad is a sound engineer. So I was always in his studio, listening to the music and learning about history and dance. I was always exposed to it in a non-traditional way.

I took myself more seriously as an artist during my last year of high school. I was considering doing an art program for undergrad. I didn’t find one that fit my needs in Kuwait so I did visual communications — more like graphic design. I was very conceptual about things, and I remember I had a professor who [reminded me that] I was in a commercial design program and what I was trying to do should be done in a fine arts program — it wasn’t what they were doing in [the visual communications] program. There was always a clash between the world telling me that my interests weren’t really a thing that existed or they weren’t a thing for me to be doing. But I was always like, “Why not?”

TH: How did you get from there to art therapy?

FS: I was working as a graphic designer in Kuwait, doing a lot of branding and advertising. It was very much market work. It was fund for a while–doing the creative aspect is fun and I respect designers who invest their time in that work because it’s so valuable. Especially in a world with a lot of visual pollution. I was lucky enough to work with some pretty great studios and one was focused on resolving visual pollution–especially in Arabic graphic design. I learned a lot but I also realized that in order to succeed and grow in that career I would need to open my own design studio and I really didn’t want to do that. It was so fast-paced and if you wanted to stay afloat, you may have to design for companies whose values don’t align with mine.

I also felt isolated being on the computer all day. Sometimes it feels like if you don’t have a personal relationship with the client and your values don’t align, you’re left to wonder if they’re taking advantage of you because they’re giving low pay but making money off of the designs you did. It felt like it wasn’t for me.

I considered doing an MFA at that time and started looking at schools, but that investment didn’t make sense to me. I had one chance to invest financially in something that would sustain me as an artist and give me a career I could live off of. Not everyone thinks this way, but I do my financial planning. I don’t have a trust fund–I have total respect for people who do, but that wasn’t an option for me!

I came across art therapy because as a designer, especially doing graphics, I was always on the side of psychology and art. But I was doing the icky part where I was manipulating the masses to buy shit that maybe wasn’t helpful for them or their lives. There was a conference I would volunteer for called [Nuqat] in Kuwait. It was a platform highlighting creative education, culture, and the arts in the Middle East and North African region. I was always assigned to work with the speakers who came in. I would build the most amazing relationships with people across the country. More and more I started coming across art therapy and seeing the links in terms of research and how it could give me the content that I needed to develop as an artist. So, I just went into it and here we are.

With the theories I learned about, I took from them what I needed. I’m continuing to enjoy working with people and supporting them.

TH: It’s interesting, too, to think that when you were studying visual communications the response to your ideas was that you were putting too much into it, conceptually. Then, you go to art therapy before landing into a studio practice. Did art therapy get you closer to being able to feel free to dive into the conceptual musings you had?

FS: To be quite honest, when I first arrived, I had an idea about what this could provide me. I was shocked to realize that it didn’t give me what I was looking for. I learned that, again, I had to do the work to extract what works for me and make it work for me. That seems to be a theme for me. I thought being at SAIC, it would mean I would get access to both the art therapy piece and the artist piece coming together. I was shocked that it wasn’t going in the direction I’d hoped. But I made it work for me. I advocated for myself, built connections, applied for the studio space — I feel like I did two degrees at the same time. I actively built the bridges for myself. It’s really hard work, but worth it. I didn’t come here to not fulfill what I was looking for. And, like you said, it did get me closer, but in it’s own way. Not in the way I expected or envisioned. And sometimes it’s okay to accept that.

TH: I completely relate to that experience. My studies were in art history and also visual arts management, but I realized, in that program, it was geared toward a certain type of work in the arts that I wasn’t necessarily most interested in. So, I also went into and through a program realizing that I needed to work to get what I needed from that. You mentioned that there were theories and things you needed to choose to take and also to leave — what were some of those things?

FS: One of the biggest pieces was that, and I understand and know that I came to study in the U.S., but I expected that since there was a big international community and student body in the school that there would be more of a global view. But I felt so much of it was U.S.-centric and that was a little bit isolating. I’m happy to learn about what’s going on here and I understand that I’m working here. The majority of people I’m going to eventually support have grown up in the U.S., so I’m happy to learn. But there wasn’t much interest [in me], especially as an artist who is trying to contribute something relevant to other parts of the world. It felt like if it wasn’t relevant to right here [in the U.S.] and right now, then it didn’t get looked at.

TH: Was that in critique and discussion spaces, and when people were reading and giving feedback on your work?

FS: Yes, it was in reads of my work and also the content I was learning. It left me a little confused — the idea that something is only interesting and important in the art world if it’s relevant to here. I think there is so much to learn — and be open to — from other perspectives of the planet. There are so many places…

TH: So many!

FS: This is not the only place on earth. So, that was me deciding to take the learning that’s actually going to serve me and the people I’m working with, and help me build relationships with people. And also help me integrate and adjust to this culture that I’m becoming a part of. But I’m also going to hold onto my truth and my voice through my art. And this means continuing to make work that is meaningful to me.

At first, I was shocked to see that curators didn’t know where to place my work. Because it wasn’t about the U.S. and things happening here. They would [default to putting] me with Arab artists. And yes, that is an honor! But it’s also interesting to have conversations between artists from multiple backgrounds, in my opinion. I’m not a curator, but that’s what I think.

TH: That raises questions for me about what it was that made it hard to place the work. Is it form? Is it content? When I think about an artist’s work, or your work, and the conceptual themes in the work, there’s often other connecting points between that work and other artists’ work that transcend geography, nationality, ethnicity — all of those things. It’s still troubling to think that your work would be limited to solely being placed with other Arab artists. There are other connections to be made.

FS: And maybe that’s just the first crowd I was thrown into when I moved here. Now, I’m beginning to meet more people who are aligned and interested in the work I’m doing. But that’s what was happening when I first came and was thinking through what was happening, the knowledge I took, and what I decided to apply to work in order to make something meaningful to me. I continued to believe that the right people would see it, engage it, and find meaning for themselves. That’s really precious: the relationship with the audience and the internal/external realizations that can occur; the shifts of perspective that can come in practice, and interpersonally.

TH: What turns did your work take at this point, when you started the art therapy program?

FS: I was continuing to work on some projects that I started right before I entered the program. As I dove in more and more, more things started to develop, bubble up, and make sense. In fall 2018 and spring 2019, that was my last year in school. So, that fall of 2018, I did a solo exhibition at [SITE Galleries] and that was a case study for my art therapy thesis research. It was a way of bringing together what I was doing as an artist for the past two or three years, and linking it to thoughts and reflections I was finding in relation to the work I was doing as an art therapist in training. That exhibition, titled Invisibly Visible, was dealing with multiple phases of the ‘Abaya garment. The type of design that I was working with was the one I grew up being exposed to in Kuwait. I was looking at it as a communication tool and portal that takes us to different moments in history. In some ways, I was trying to challenge people’s perception of the identities that are associated with these garments — whether from a Western gaze or Arab gaze. It was me thinking of this garment as a material. It is a portal to transport us to different ways of thinking. I’d done five works that respond to it. There was a sound piece and poetry book created in collaboration with Manisha A.R., who is a writer. This was my way of de-exotifying whatever people were coming in with, while at the same time making it accessible because I wasn’t going to write a full essay on what the work is about. I have a lot of information and I do a lot of research, but I’m not a historian. I will poetically speak to you, and you can read between the lines and arrive at your own meaning of this work.

In that body of work, and because of the portal piece, I began to think more about time. And I’ve gotten deeper and deeper into thinking about geological time. Like, all the weavings I have woven are based on mainly desert landscapes like Antelope Canyon and the Grand Canyon. And time speaks to the themes of the visible and invisible. I’m getting deeper into a sense of time that isn’t relevant to the one that we’ve constructed and the one that influences our perception of what reality is.

TH: Can you talk more about what role portals play in your work and how you’re defining that?

FS: There’s a ritual that I’m engaging in when I’m exploring a material. These [weavings] are based on photographs. For a while, I was using photography only — I still go back and forth to it because there’s something really powerful in it. [Photography] is where my understanding of portals came from, I think. I was handed a camera when I was like 14. I started by understanding time through photography.

Then there’s something powerful about reproducing the content of the image through another material — that’s the ritual. It’s almost a documentation of the ritual or a vessel that contains the time. When people view the work, my hope is that the way the materials are put in this new vessel, new body, or new way of reframing it — I hope that will bring them closer to their own portals.

TH: You’re using so many different definitions and metrics of time. You mentioned before that your mother was a seamstress and did sewing and your father was a sound engineer. I don’t want to assume that alone is the motivation for your explorations in mediums, so what drew you to push into things other than photography?

FS: As you mentioned, from my childhood I was always exposed to different mediums. The point when the camera came into my life, I was dealing with grief from losing my mother. That was a way for me to begin to think about what was happening inside of me and why I couldn’t understand the feelings. Something in my understanding of reality and time changed — and that’s what trauma does to us. I was too young to understand. I was 10 years old when I lost my mom. But the camera was the tool that began to give me a way to process [the grief].

I felt so powerful and in control for the first time. I was also at the developmental stage where I was questioning my identity. This is the stage where you think more about your social and emotional sense of autonomy. When something traumatic happens, you suddenly feel so out of control. I felt that [the camera] was a tool that was giving me a sense of control and, in some ways, connecting me with her. When she was around, I was always next to her doing some art. I [was in] shock when she died. I didn’t know what to do. In a way, the camera was a new understanding [of myself].

When I would photograph the things around me, they would have themes of liveliness. But then when I would photograph myself, I would do dark black-and-white self portraits. They were meaningful — especially when I didn’t have words and was in shock. But, the camera became a doorway to thinking about what was next for me.

I started exploring painting at 19. At that point, I was getting frustrated with the frame of the [photographic] image. Maybe it speaks to the developmental stage I was going through — I was an adult and wanted to be free! But, in my culture, society frames you — a woman in that age — as still being young, needing to follow your family’s rules, and, for example, have a curfew. There was a [conflicting] social messaging and internal voice saying, “I want to be free!”

It all has to do with phases of life for me. I started playing with painting, then mixed media, and eventually went back to photography because they were my roots. It was where I needed to be.

I realized that I’m not a good painter. I enjoy doing it in art therapy sessions with clients. It’s also a good medium to help me move my thoughts around when I feel rigid. For certain thoughts, I felt limited by photography. I wanted to give myself permission to take from photography what I need and letting go of the rest. So, I’m still connected to photography, especially in the way that I look at things and how I understand the position of power [that comes from] framing and presenting a thing, a portal, for viewers.

TH: Looking across your work there is still a visible commitment to photography — so many are based on photographs.

FS: Yes, the screen prints are based on photographs. And the weavings. These polaroid emulsion lifts are still photography, but literally breaking the frame. I’ve always been fascinated by Polaroids. The best way to preserve them is to do this emulsion lift process because it fades over time. On some surfaces, it looks good and with others, it’s crumbling and falling apart.

[I like to] think about the ritual of engaging with material and the many places it can take us and our thoughts. There’s a lens of multiplicity and intersections. Each person will respond differently, and hopefully find something meaningful within it.

TH: When it comes to art therapy, I think of how it’s used to process our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. But, I’m curious, how do your studio practice and art therapy practice overlap or diverge?

FS: I’m in different spaces with each of them for most of the time. When I’m in the art-making space, it’s a different process. When I’m in the art therapy space, it’s about the person I’m working with. It’s not about me. It’s about building a relationship with that person and the thing that we create together. I approach it with a relational lens and look at what healthy relationships look like and the related disconnects and challenges. I’m there to empower and encourage the people I work with to continue to find their agency and voice. We’re also looking at ways that art materials can uncover new perspectives and how to integrate changes they want to make for themselves. Art is a space to envision the possibilities. We don’t always allow ourselves to have a space held for us to process in other ways. Sometimes that can be the access point to begin to see the goals we have for ourselves and the changes we want to see.

TH: Do the material explorations that you do with your clients ever influence your studio practice?

FS: Yes, absolutely. It’s a cycle. One of the biggest lessons for me is to learn how to be intentional about how I present work, how I engage participants, or facilitate. I learn more about the themes of visibility and invisibility — my art therapy practice is very private, especially for the people involved. There’s a sense of trust that is put in me, and that’s such a privilege. There’s also a responsibility as an artist when it comes to the public and how they engage the work; also me being intentional on how I present things; also fact-checking as much as possible — I’m not a historian and I don’t know everything about everything, but I want to make sure what I’m putting out is [accurate and] intentional.

FS: Yes. I’ve been collecting these [films and cameras] since I was about seventeen years old. I was obsessed with instant photography. Unfortunately, by the time I was in my early twenties, there was no more film being produced or the film had expired. Then, [the efforts behind the film] An Impossible Project came along [which was an attempt to save the world’s last Polaroid factory]. It was experimental and the chemicals [to process the old film] weren’t always right. There were a lot of times when the chemicals would just do what they wanted, and the photos I wanted to make wouldn’t turn out. It was really out of my control — the photos were always fading and changing. There’s always a moment when you think you’re in control of capturing that memory, but really it’s up to the material and what it wants to do [and record], which makes me think about trauma and stress — the things in our lives that are out of our control. These systems that we live in are always trying to predict the future and put things in boxes. But things go out of control because that is the nature of life. There is an unknown that will always exist. I think these pieces speak to how the psyche works and how interruptions happen — how there are holes in our memories. With these Polaroids, I started to collage on them one day while thinking about what it means to intentionally bring in new landscapes into our psychological landscapes.

TH: Memory is such a complicated thing. And I love these pieces as a metaphor, though they seem like something more than that. But very clearly mimicking exactly how we recall and remake memories over time.

FS: That goes back to my work not being a tricky metaphor, but a multiplicity. The time and context for these pieces are always going to shift. That moves me into this other work. One thing that influences my way of thinking is how arts or dance and music traditions in the Arabian Peninsula have traveled with migration. When they settle, they settle to meet the needs of the community. So the works become contextual — they were created in a certain time and way, but as they travel they [adapt to] meet certain needs of communities.

This work is based on a tradition called Zār that started in East Africa. From my understanding and research, the style of Zār that we got in the Arabian Peninsula is from modern-day Ethiopia and up into Nubia (Sudan and Egypt border), then it came down to the Arabian Peninsula and made its way into Kuwait. It’s a form of art and healing that came from African migrants and was shared with Arabs. There’s a lot of rich history there, especially in terms of crossing cultures between Arabs and East Africans. The way Zār evolved over time and when it settled in Kuwait is very unique. [These evolutions have inspired my] thinking and I’m finding links to it based on history.

TH: I’m so interested in attempts to recompose, whether it’s about memory, culture, practices, or languages — cultural and personal things that are disappearing over time. In a way, recomposition is also about evolutions of people, artforms, and culture from place to place over time as new things are incorporated. With this example of Zār (زار), you can see how a tradition is charged and infused with ideas and traditions of the people and places it’s moved from and to. Have you seen the differences of the artform over place and time in your research?

FS: That’s a great history question. In the book Women’s Medicine: The Zār-Bori Cult in African and Beyond (I don’t like that they use the word cult but…), I’m reading how the version that we got in Kuwait involved old deities of the region and each deity had a certain rhythm and color dedicated to them. If that sound and color calls to you — if that deity calls to you — then you participate and that is the healing that your spirit has possessed you to receive.

By the time it got to us [in Kuwait], I know they were still using different colors and rhythms, but it evolved at some point to have more to do with Sufism. Multiple genres have started to come out.

I’ve also been reading a thesis from 1985 about women’s roles in these rituals in Kuwait, by Dr. Zubaydah Ashkanani. It’s fascinating because she talks about the six genres and how the ritual is facilitated based on who the ritual is for. She also talks about how the most sacred one of all is Tanbūra (فن الطنبورة) — and I wonder if that has to do with its relevance to the region.

Under the umbrella of Zār, there are different rhythms and styles of music. The six main ones in Kuwait and parts of the gulf are Qadri (only percussions, ecstatic dance, moving body left and right), Hibshi (only percussion, slow rhythm), Samri (percussion, slow rhythms, popular outside the context of Zār), Tanbūra (the most sacred and common request for Zār ceremonies in Kuwait, uses the Tanbūra instrument, percussion, and Manjour), Laiwa, and Bahri (uses a wind instrument and percussions, not as common anymore for Zār context). They each have different types of dances.

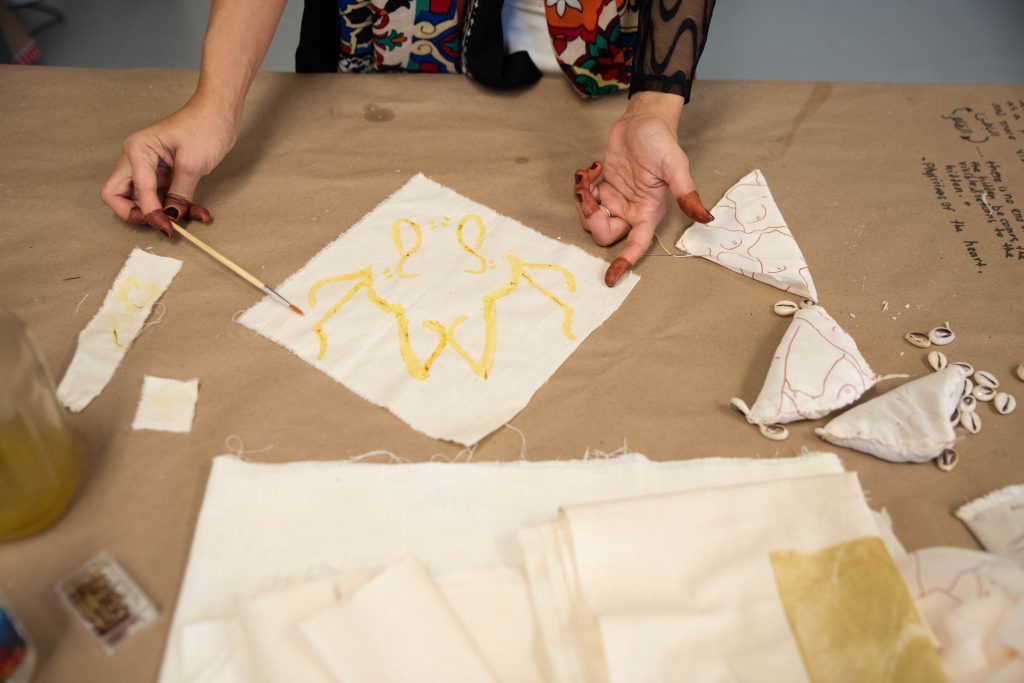

I was first introduced to Tanbūra in a way that was almost non-traditional. When I was a child, I would join these school dances and I saw boys from my school wearing manjour instrument belts around their hips made in a nontraditional way: out of soda can caps. All the moms in the school collected these cans and sewed them together for the boys. Then there were girls who were dancing with them. It was my first time seeing boys and girls dancing together. I grew up in a very segregated lifestyle, but it was celebrated for people to come together and dance a very trance-like rhythm. I was in awe of the reimagined version of it using soda can caps. In my project, I consider shifting the narrative of going beyond only men wearing this instrument. I haven’t found any information that it was also worn by women.

The manjour (المنجور or manjur) belt instrument was originally made out of dry goat hoof. I’ve been wondering if it has a link to pacifying [jinn], which means a spirit that possesses. Men wearing this instrument and shaking it has to do with men needing a controlled way of release [through a] subtle and controlled movement. In the Arabian Peninsula, jinn are named as ‘people of the earth.’ There’s one type of female jinn who transforms into a beautiful woman but her feet are always hooves. So, I wonder if they’re related, and if men used the original manjour belt to shake off/pacify this type of female jinn.

It also makes me think about how, in Western psychology, there is research coming out about dealing with trauma through getting to know it and figuring out what your trauma needs. Also, talking about how trauma is trapped in your body and shaking to reset your nervous system. These are things that Western psychology is just now claiming because they’ve had controlled “evidence-based” studies at institutions. But these are things that our people have been doing for generations. They knew, but it’s always viewed [in the Western world] with an anthropological lens that’s always othering. So, I’m looking at these links with choice of material, history, and relationship to modern psychology. Like the cowry shell, which has a lot of interesting history as a first form of economy and also of being a protective talisman for women especially. When I think about using the cowry shell, I think about that memory of the first time I heard that music and how it was a reimagined version. So, I thought to myself, ‘what would it be like to reimagine this music as I migrate and shift it to the needs of my communities?’Just as our ancestors have been doing for so long — they’ve been traveling with this art and reviving it.

TH: Can you talk more about the objects you’ve made that are related to the research?

FS: The weight of the piece really grounds me when I wear it. I even made a headpiece. And the sound it makes is very unique. It makes me think about shaking out the trauma that’s usually trapped in our hips and our stomachs, where most of our stress is. Also, I want to shift the restrictions of who gets to shake and who doesn’t.

I want to create a new soundtrack, sound piece, or soundscape that maybe brings audiences somewhere closer to the experience of a Zār/Tanbūra ceremony. Throughout the soundscape, sound-designer Mohammed Alowaisi and I are choosing to overlap some rhythms in order to speak to portals and moments in history. We start with the Hebshi, which means “from Habasha” or from modern-day northern Ethiopia. Hebshi will be the one about where Zār music comes from. We will build up [from there] and end with Tanbūra.

I’ve written poetry that is extracted and inspired by the research, but also taking and mixing phrases. I like the word you used — recompositioning. Eventually, it will be shown alongside a performance and archival video. I will also do invite-based workshops with diaspora Arab women who have familiarity with this. We will learn the dance moves and history, then interview to record their takeaways.

I’m not doing the actual ceremony because I have so much respect for the Mamas — the medicine women who lead these rituals and ceremonies. I don’t have the knowledge to do it. I’m more so trying to preserve this history that is orally-based, in the best way that I know. As people from the Arabian Peninsula, our best way to document our history and experience is through art-making – our version of art-making, which is weaving, crafting, poetry, music, and dance. That’s how we scribe our history. It is not the Western version of art-making.

TH: There are so many elements of your practices and the work that you do within this one piece. And I hear you when you say you have high respect for the people carrying these traditions and healing work. Do you see there ever being a point when you yourself will get trained to do this healing work and incorporate it into your own art and therapy practices? Is there a mergence of those or is it too early to tell?

FS: I think it’s too early to tell. I can take away some learnings and conceptual understandings, and apply that. But I don’t think applying the physical techniques is what I want to do at this time.

TH: It’s so interesting to think about these ideas orbiting one another and having the potential to collide in the future.

FS: Yes, definitely.

TH: This might be a tough question, but looking at how all of the pieces of your work and experience have ebbed and flowed in your work over time, I’m curious to know if and how intuition comes into play in your work.

FH: I think I look for leads and get excited about those leads, then I assess from there whether or not they connect. If they don’t, I’ll drop them. One lead for me came through drums — even though these drums weren’t used in or necessarily related to these traditions, I’ve found moments in history where women have had a role in playing these instruments and creating a new sound. But their contributions in musical history aren’t documented or appreciated as much as it should be. I think about how I can link it to preservation. It’s a type of music that started with women in East Africa. The research I’m looking at by Dr. Zubaydah is based on women in Kuwait in the 1980s who were middle-aged and felt alienated by the speed at which things changed after the oil era. There were all these moments in history that weren’t being preserved — and still aren’t. So, I look at these materials as guides to lead me to make these connections. I don’t know if that’s intuition. Maybe it is. Or maybe it’s internal links happening — metaphors I’ve always known but didn’t know where to put them. Maybe it’s recompositioning.

TH: To me, your work is a type of archival practice. And I love how you’re evolving objects, ideas, and traditions by deconstructing it and putting it into a completely different form — like these instruments.

FS: Because of how we are presented with certain information, we become — not necessarily dismissive, but maybe desensitized. We scroll, we glance, and we move on. When that is interrupted, you’re forced to pause. In my work, I’m trying to get people to stop and think about things like erosion and time — like how long it took for our landscapes and these forms to take shape. I want to begin to open up new possibilities and ways [for people] to stop and think about time.

About the author: Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Matt Austin.

About the photographer: EdVetté Wilson Jones is a Chicago-born artist, photographer, poet, performer, and storyteller. During their childhood years living at the Cabrini Green housing projects, EdVetté was introduced to acting through the work of Chicago theater legends and veterans Jackie Taylor, actress and founder of Black Ensemble Theater, and the late Patrick Henry, founder Free Street Theater. From there, EdVetté’s practice grew to include not only acting, but screenwriting, storytelling, poetry, journalism, fashion, and more. To learn more about their work, visit their website at edvette.com.