A few seasons have passed since this interview with artist Erol Scott Harris took place. Though, when I read it back, it still feels like it happened yesterday or just last week. It was only a little bit ago that I was in Erol’s studio, in almost the same way I was for the first time in 2008 (or was it 2009?). I was sitting in front of a painting that made it clear to me that Erol was an artist who would be in my life for a while, in one way or another. His work has consistently poured into the well of reasons why I love painting—especially Black painters. And, in an even more lovestruck way, Black abstractionists (a term that I’ve been continually crafting my own serpentine and shapeshifting definition of for at least as long as I’ve known Erol). I don’t remember what classroom we were in or the circumstances that led to our first hello, but I do remember ending up in Erol’s studio very early on. And spending hours there, falling soul-first into his paintings, and feeling changed after leaving.

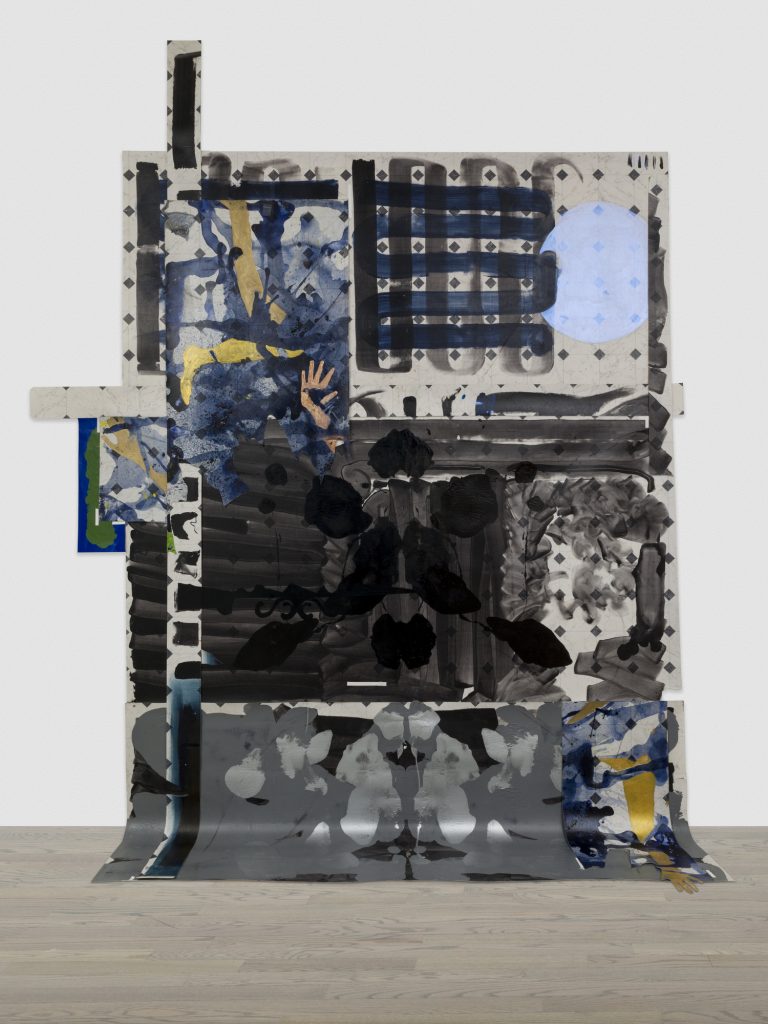

Something that has been consistent in Erol’s work, in the most releasing and liberating way, is its ability to expose the inadequacy of words. It is unyielding in its request that you interpret it somatically. In my attempts to describe what I’m seeing, I stop because I can immediately see how my words are inhibiting rather than enhancing my experience. I don’t want to create distractions or barriers between the work and my senses. Erol’s work is best experienced in silence, or in soft whispers, quiet reveals, and patient observations. It’s meant to be savored, relished, and, by doing that, discovered. It’s meant to be re-experienced and interpreted over time, with welcomed and expanded revisions. Should you take up his invitation to sit for a while, whether in his studio or in his canvases, I recommend you approach it gently, but also prepare to receive waves of information, cleverly buried imagery, glimpses of immediate and distant ancestries, and access to sweeping studies of internal worlds and materials.

One of Erol’s pieces that has continued to haunt my thoughts is Taproot, a small oil painting on linen that he made in 2014—a piece that, when described by Erol, provides the type of infinitely unfolding language that his work requires. About Taproot, Erol has said, “In 2013, I pinned a dandelion to a board, sliced open its stem, and over time watched it dry and rot. Severed from its taproot, the luminous yellow tones of it bloom and the milky limes of its stem shifted to deep umbers. I realized I, too, was severed from my mother’s taproot at birth. Eventually becoming a shell, a skeleton, devoid of liquid. I must confess, as time passed and seasons changed, [I’ve found] myself immersed in a studio of dried roses, still listening to the color shift…marinating in the way I rot. But this time, pinning my physical body against surfaces.”

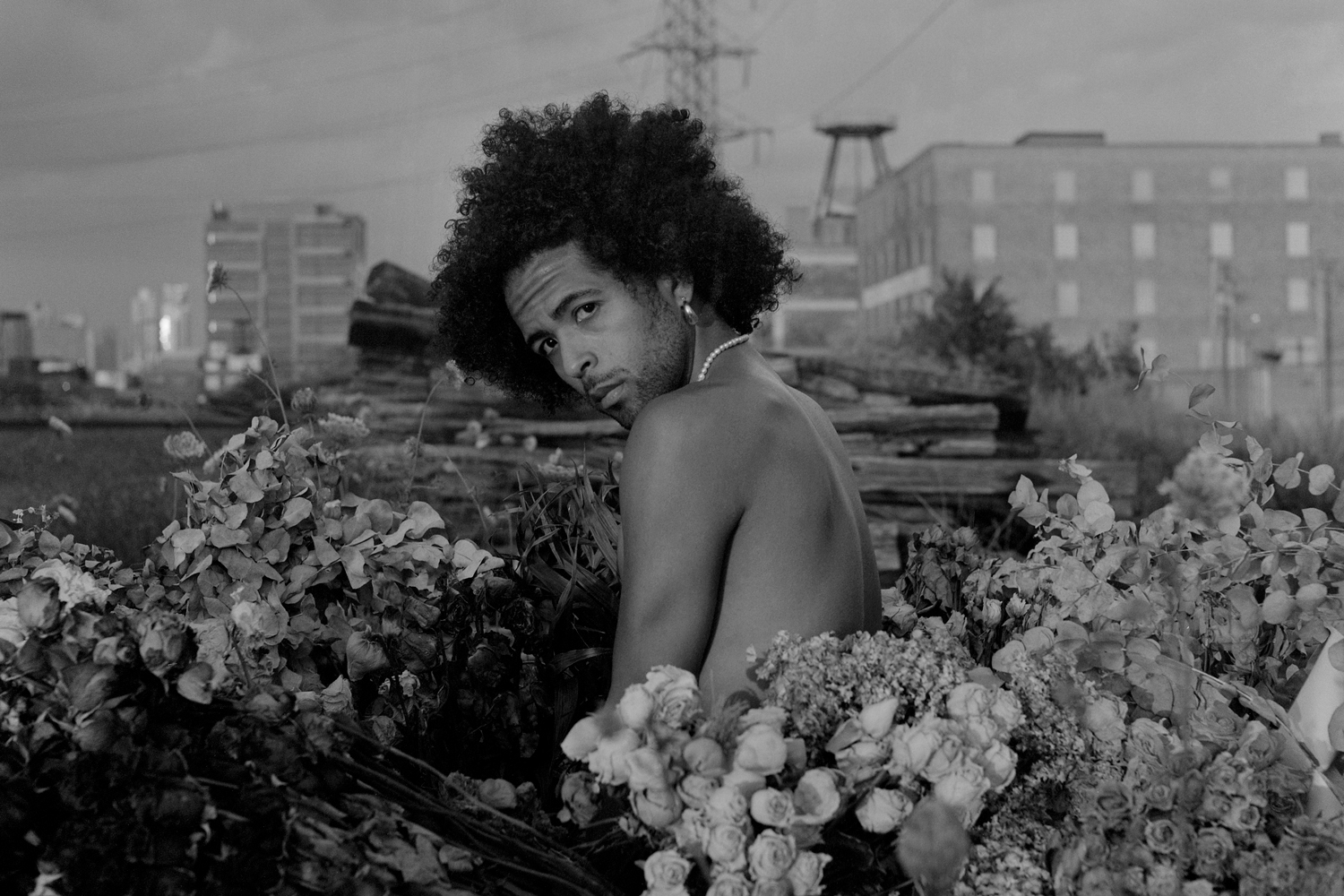

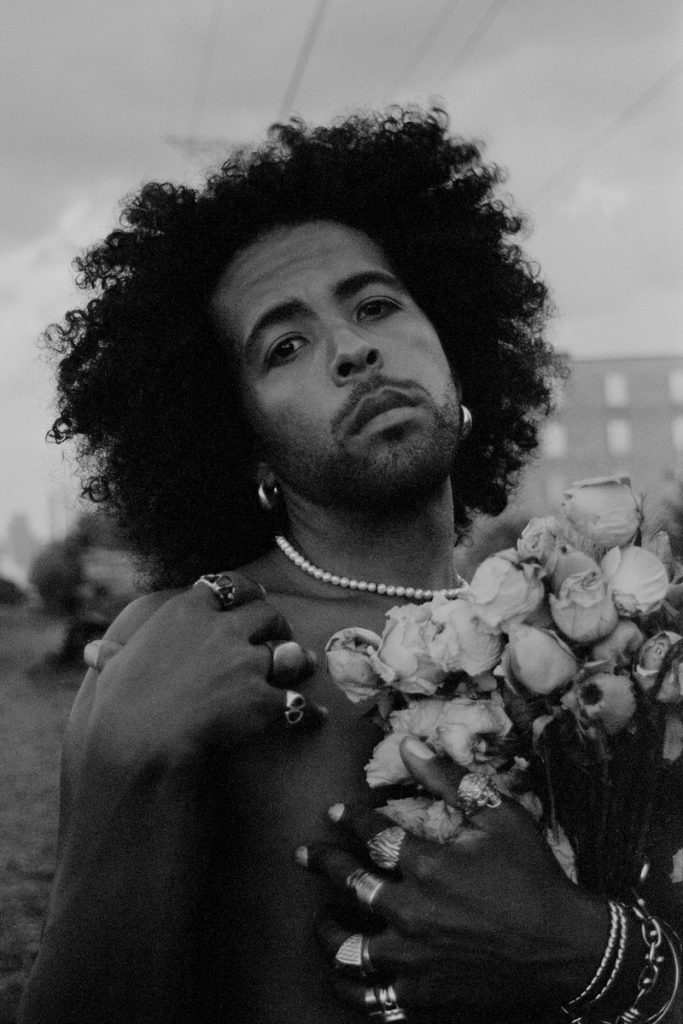

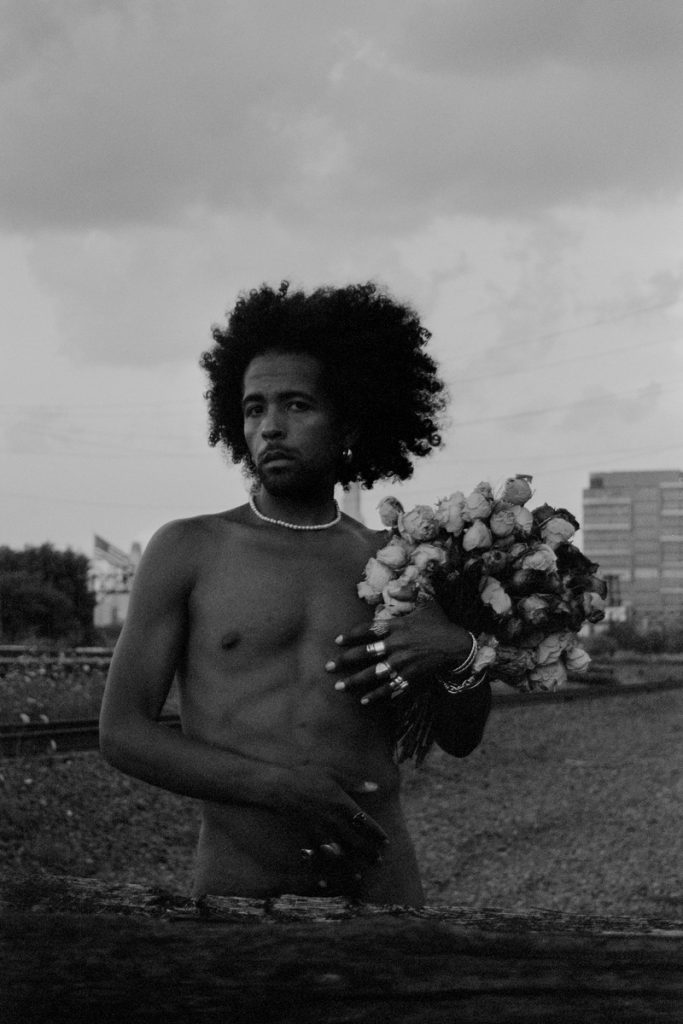

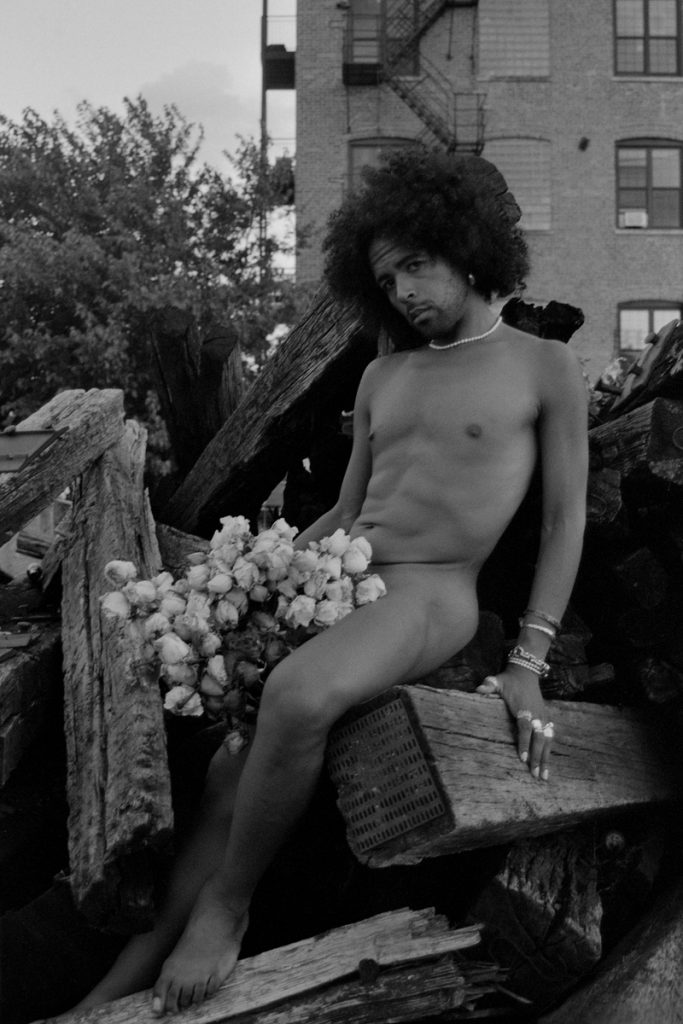

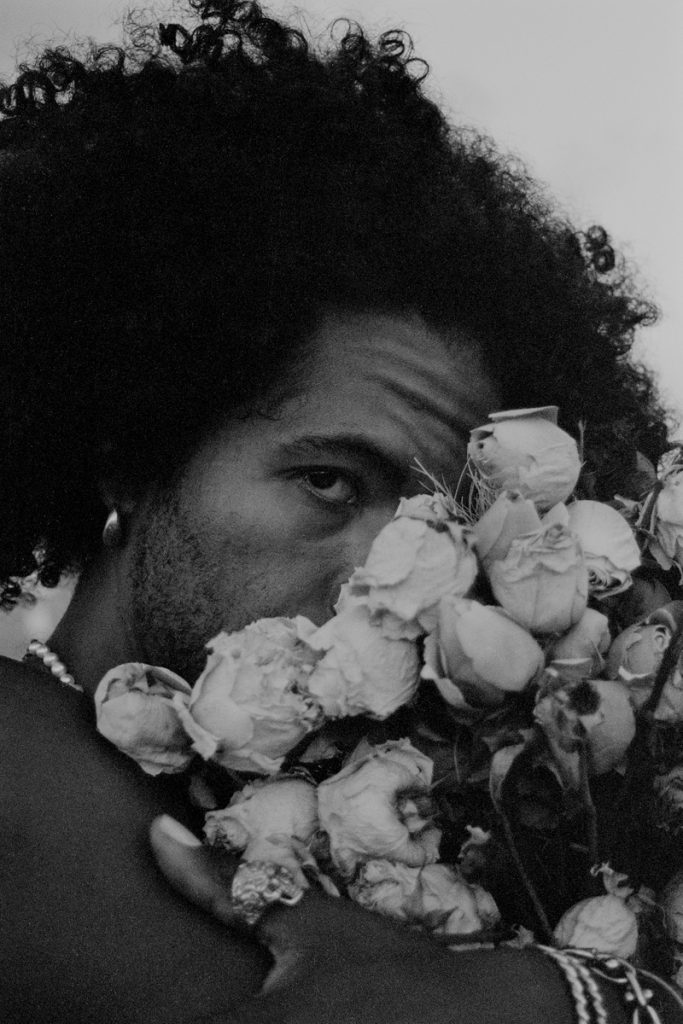

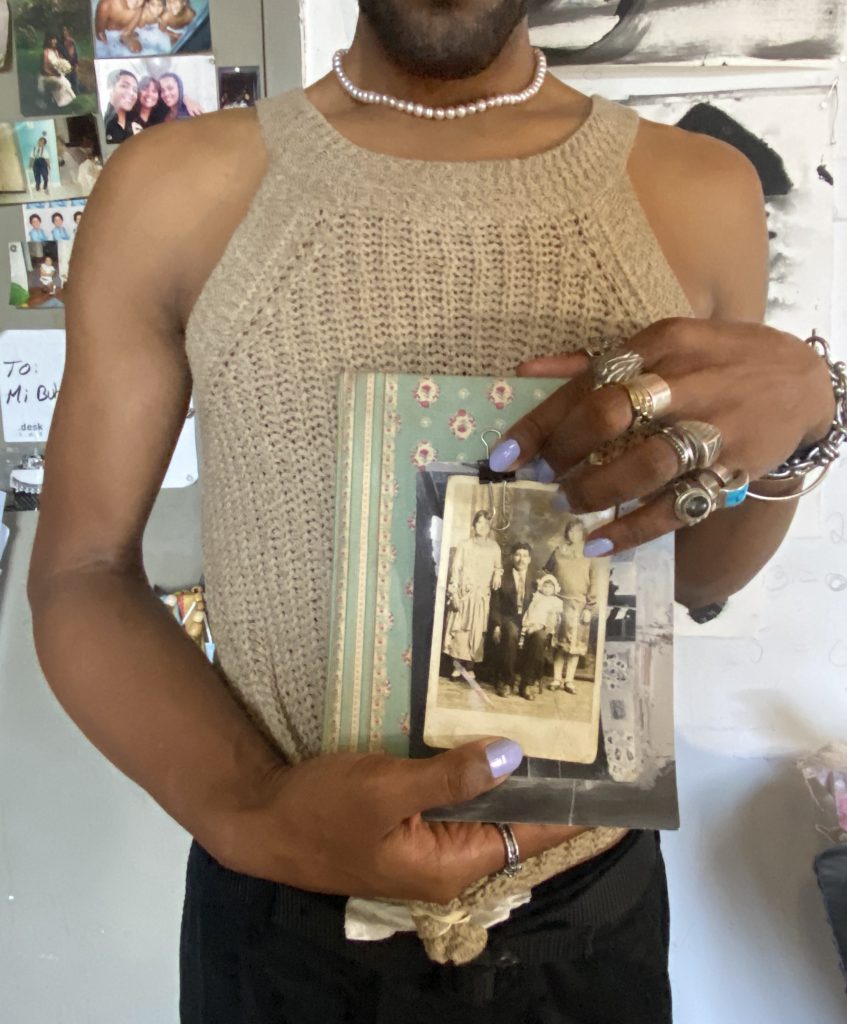

The following conversation contains a little dose of déjà vu and my deep appreciation of Erol’s ability to find words where mine fail. As you read, imagine Erol and me among hundreds of fragrant and wilted flowers. At our feet are a few new works in progress, the walls around us resemble the collaged pages of sketchbooks. Over our shoulders are a couple paintings that have witnessed many things, including the evolution of an instinctual prediction I made a while back that we would be sitting here together, on new occasions, me continuing to fall in love with his canvases. The following is an edited excerpt and snapshots from our studio visit, paired with beautiful portraits taken outside of Erol’s studio by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

TH: As someone who feels transitions deeply, I have to start by asking you how the current season transition is treating you.

ESH: It’s like being reborn, rebirth! And everything smells really good. It’s like a ghost and a memory. It feels like it’s going to be a really abundant year. And it has been.

[In my work], I’m usually more into moodier colors, like November and December tones, winter tones. But there has been a feeling in me to embrace more of a lighter color, more pastels and iridescents, and I think that it has to do with just being at another point in the pandemic. Everything feels like it’s fresh and new.

TH: I want to know more about where you are when it comes to your work, your painting. This year you’ve been making quite a bit of work and really exploring new but familiar territories. We’ve known each other for a very long time…

ESH: Oh my gosh, yes.

TH: … and I am curious to hear how you would describe your work, your practice, and yourself as an artist right now, at this moment and after all these years.

ESH: When it comes to articulating who I am, where I am at as an artist, it always falls outside of just being an artist. I think it’s about how to be a human. I’m always asking that question first, and the artistry is something that I just happen to do. Art gives the closest thing that I can find to an answer when asking myself what it means [to be] human or when tapping into a deeper part of myself.

I’m in a space where I can ask myself for more. More silence, more of not fighting to get anywhere. Not trying to pursue, pursue, pursue! And I’m not finding myself traveling all over the world like when I was art dealing. For once, I’m just quiet, and that’s bringing in a lot of new knowledge. A lot of what’s been coming up are memories of me with the land. And longing for the land again, and wanting to leave, because I’m so disconnected from the 9 to 5 [work life]. That’s part of why I got into dipping myself into the work more. I want to see the material under my nails. I want to have it in my pores. I want to wash it off at night. That feels right.

TH: Is that where it started for you? Is that the same energy that you had when you first started making art?

EHS: It did! I used to work with soft pastels and I used to work on tarp, because it would chalk off and it was kind of soft. It was a gentle poof at the tip of your finger and you could really push the pigment. If you are feeling angsty, they say eating carrots is good for you. So, it was almost like eating carrots. [When I started painting], I was a very angsty young teenager. Processing a lot, you know?

TH: So you were doing that type of work on tarps and with pastels as a teenager?

EHS: They were huuuge! Tons of colors all over, and written words, with smiley emojis and missiles floating over, with everything in one color field. It was always in one amorphous form, no negative space.

TH: When it comes to that work, where do you feel that the elements or the energy of it have maintained themselves with your practice in the years after?

EHS: The tactility? Yes, one hundred percent. For a while, I had to grapple with seeing that work as being secondary. I was seeing it as not refined. I thought I had to tighten it up and put it into a tighter, formal box. I had to give it a subject. But now I’m back to bigger arenas, which is nice. And it feels good to put my body into [the work] again, and put my fingers into it. I am creating, and dipping, and pressing, and doing those types of things right now.

TH: You’ve been talking about the move from the way you were making before you went to school, or before you went to Columbia specifically, where we met, and then the way your understanding of your practice shifted later on. We are glossing over a huge period of time. Can you talk about what it takes mentally, emotionally, and spiritually to move between those places? And perhaps how the stakes are different?

When you were a teenager, was there freedom in who you were making work for? And as you moved into college, perhaps you were making work thinking more towards entering into an arena of the art world while trying to find your place within that space. Then, after moving to a post-school stage, did things open up? I’m curious about transitional points when your practice—or your understanding of it—changed significantly. How did you have the confidence and the wherewithal to make those decisions?

ESH: One of the things I think most about—whether I was in high school, at Columbia, in a [my] post-Columbia period, or now—is the internal space I’m working from. I have to see with my heart and my gut. The forms [that come out] correspond to my internal learnings, and my heart, or my gut, or any part of me [that] is opening up a space [to create]. I’ve always known that I have all this cerebral information all around me, so when I sit down in front of a surface, it’s all going to resolve itself. And it will be my space and place for a period of time.

I think this has to do with growing up in so many different homes. The canvas became the space where I really lost myself at a very young age, you know? There are photos of me out there in front of an easel when I was really little. Even when we were moving, living in basements, I had my easel and I had my paint. There was a certain type of imprint, an enmeshment that happened with that experience. It’s how I manifested things early on. As a little kid with that easel, I was setting up intentions for myself that I didn’t know. I felt wise beyond my dreams and [the canvas became a way for me to put] on my armor, let’s say.

When you were talking about digging back to my old ways of working in high school, I started thinking about working on the farm. When I left Columbia, I went to work on a farm and I was excavating, I was weeding. I was out in the field, weeding for six to seven hours a day. Everything was corresponding with what needed to be done. And that’s how I am as a painter, too. I find myself in these places where I’m doing something that corresponds cerebrally to what I am doing physically. But I have no attachment to either of these [processes], I am just witnessing them. I’m watching them unfold until I get to a point where it’s done.

TH: That makes me want to hear more about your relationship to discipline. Whether within your practice, within your life, within your upbringing, or even within the discipline that came with working on the farm, are there threads that connect your various experiences and understandings of discipline—in all its different definitions?

ESH: Yeah! You know, my mom was a single mother, though my father was still very much around. [My sister and I] went with him every weekend. But my mom was always so busy, so we had to get ourselves ready for school most days. My grandfather taught us how to iron our pants very well, how to tie a tie, and how to keep everything really clean because we could only afford one pair of pants each and one polo. So, we had to make sure that it was very clean. If they ever got dirty, I would always make little designs and stuff on them. This taught me that the external world has a formality, has a certain code, and within the abstract realm of my family experience I had to keep [everything that contradicted that code] encapsulated and tighten things up before I go out [into the world].

Another discipline comes [from] playing cello. I played saxophone first and then cello after that. Discipline was always something to propel us forward, but was never intended to be a way to tell us what to do. It was much more of a tool to use as we saw what was going on in the world. So, everyday, I’d come back home and take off the discipline, set it aside, and spend time with an abundant family that didn’t press me or pressure me. I just had paint and material, and my grandpa’s garage where he’d just be working and let me do whatever I wanted. [Discipline existed across two separate worlds], and one didn’t have to know about the other, though the two realms exist simultaneously and I operated in both of them. And that’s kind of how I’ve always been. My public and private lives are very public and private. You are probably the fifth person who has been in the studio. I’ve always been known as, “Where is Erol?”

TH: That’s so beautiful—what you’re saying about being disciplined, ironing your pants, going out to work on the farm, and then, when you were younger, typical teachings of discipline not being imposed upon you within the family space. There’s also that familiar family teaching of not showing or telling your business out in the streets and making sure not to give people reasons to worry about anything that they don’t need to worry about. That’s the type of thing your elders or your parents would say, ”Don’t go out into the world looking a mess! Mind your ps and qs…don’t be out there making us look raggedy!”

So, essentially your canvas was your sacred space, a space that held you and that you could fall into. But you were also someone who naturally and was being told to pay very close attention to the world outside of that space. How do these things exist together and is there a tension there?

EHS: In past experiences, I always wanted to be painting. But [in school] we had to talk about the work, too. I listened, but I was always thinking about the painting that I needed to do. Before I went to Columbia, I was painting everyday. [Though I would’ve rather been painting], some things were very informative, of course. This is when I learned a lot about abstract art, and other things that really influenced me. People like Hilma af Klint. People like that were very important, and I had no idea about their practices. So, that helped me find connecting lines in my work, especially because everything in my work was so amorphous and to the edge. The more I learned, the more I realized how I could insert different elements into the arena of a painting and give them space.

And then there’s critique, you know? I remember once [my classmates] were trying to destroy a painting of mine, saying it looked too dated, the tone was outdated, it was too surrealist and muddy. It was not bright or vibrant [at a time when] everyone was using bright acrylics. At the end of it, I figured that I succeeded because they talked about my piece for the longest! At that moment I realized, no matter if the work is “good” or “bad,” it doesn’t matter—it’s energy. And, in the end, that energy doesn’t even correspond with the energy I felt when I made that piece. My experience making the piece is more important than whether it’s good or bad. When you can make from that place, when you are that connected, everything else is just part of the ride.

TH: There are artists who make work that is very beholden to the world around them—it’s hard not to. And, like you said, there are trends in artmaking, and there are people who are swayed, pushed, pulled, and deeply influenced by that. To feel like you don’t owe attention to any of that, and to be able to hold the value of your work for yourself in that way, is really powerful. How have you felt secure in the work that you’re making so that you’re able to self edit and not be thrown by what other people may toss your way, and that may not be serving your intention at that moment?

ESH: It’s been a saving grace how I have built a process. At the end of the day, I know what has to be done, and I just have to sit my ass down and listen to higher forces. And that’s all. Then I’ll be directed. I just have to listen and let it become a channel for whatever has to come out. So, when I’m off gallivanting in the world, trying to pursue a career or people’s perspectives, I am not sitting still. I am not in my silence.

TH: Sitting in the silence and listening, makes me think about, again, “Where is Erol?” You spoke previously about being on the farm. Can you talk about why you made the decision to sit or be in that space for an extended period of time? What led to that time on the farm?

ESH: [Leading up to it], I was working to become something that I didn’t want to be. Deep down, a part of me knew that I wouldn’t be able to sustain being the artist I was in undergrad. It was weighing on my physical health, my spiritual health, my mental health. I wasn’t prepared to go off and be alone as an artist. I didn’t fully know myself that well, and I was done with all the egos and archetypes. So, I went back to the farm and let myself work there for two and a half years. And I shut off.

The people working on the farm were mostly [undocumented]. I got to hear the stories of how they came over. Their stories had a deeper connection to my roots and lineage because they came here like my grandparents did. I was staying at a homestead. I would be scratching and etching drawings on the barn. I would bathe in the creek. I was just wholly immersed. The whole city was still doing its thing, but I was there. I was watching chaos [from a distance], from a nest. I hunkered down and told myself that I didn’t need [that kind of artist life]. It’s not healthy to be that thirsty. Thirst is not going to get you where you want to be. And maybe I altered my universe by doing that, but so be it!

TH: You said “go back to,” what do you mean by “go back to the farm”?

ESH: When I’m saying “back to the farm,” I’m meaning go back to the internal farm. Like, go back to the only origin I know—to home, [to where I was born] in Waukegan. [It’s] the beginning for me, so I think that’s why I circled back to it. I was doing a lot of wild harvesting. I knew when the wild mulberries would grow and I knew when the fox berries would bloom in August. I knew when the mushrooms were coming up. I wasn’t going to grocery stores. Before I went to the farm, everything was so controlled. My practice was controlled, too. I had gone from high school and being completely free, to being in college and completely controlled. And here I am now in my little space that manifested itself completely without control. And now, I have a new venture here.

TH: What marked the time when you said, “Okay, I’m ready to leave the farm?”

ESH: I just stopped. I wouldn’t want to go in. My body hurt. I was done. I was full. But a couple of months before I left, I was going back to painting, and I started making a farm series. I started to really just push out work again, and I was feeling like I wanted to get back to going to events in the city. I started going to small events—I think one of them was yours! It was maybe your birthday party at someone’s house. It was my first event, and it was also why I felt so comfortable—because you were there.

TH: How was it to transition back?

EHS: Good! Well, I actually started to work with kids. I went to teach. I was an art teacher for a little bit. I worked with kindergarteners through 8th graders for three years. I was still shut off from the city, but I was coming to do events. It was cute. I was getting closer to humans. I was studying with the kids. I felt good. I got filled from the land, I got filled from the kids’ love. “Mister Harris! Mister Harris! Mister Harris!” I did that for three years and got to see them grow up. Then, I got the gig at Kavi Gupta Gallery, ended up in the pandemic, and now I’m here, embracing my own sanctuary in Chicago.

TH: Which is beautiful. A lot of that time spent tending to the land and to yourself allowed you to spend more time with your own ancestry, your heritage. Things that feel very ancestral. Is there anyone in your family or ancestry who comes out in your work sometimes?

ESH: Oh, wow. I would say my aunt, Aunt Christina, and my great-grandmother who I never met. She was known as a curandera. I feel her sometimes, I think of her sometimes, and I just feel very protected by her. Her name was Violet, like a flower, which I love. The mythos of the family is that she materialized a flower at her sister’s funeral. That’s always been the story. The Mexican side of my family is big on telling stories. I don’t know if they’re true or not, but that was one that I would always ask about. I remember being a kid, looking at my hand and saying, “IT’S IN MEEEE!” You know? So, I’ve always had this connection to flowers and nature, and wanting to materialize nature out of a void. So, Violet comes out. Then, there’s my aunt Christina. Though she passed, she’s always been an angel to me. She left behind a bunch of books and recordings of things she wanted to say to me after she wasn’t around to say them. I found them when I moved back home to go work on the farm, in my grandma’s basement. There was a chest full of videos, voice recordings, and audio books! She would be talking about travel and telling me what I did on that day. She would give advice on what to do in different situations. She helped me realize the importance of art again, and the importance of silence. She did that for me! I feel very connected to her, you know? Deeply. Because she left all this behind. She always carried around a video camera—like the ones they used for the 12 o’clock news, you literally put a whole damn cassette in!

TH: A whole VHS!

EHS: Yes! So she left behind a bunch of those. And, watching all of those videos, I could see how I behaved as a child. I was watching all these videos, bawling my eyes out and decompressing from trying to be an artist in Chicago, becoming somebody. I was the first to go to college. I sometimes had to try to be the father figure in my family a little bit since I was the oldest. I was watching my childhood unfold on film while going to the land and asking, “What is all this? What does it all mean?” I often think of my life as still under her lens. Like she still has her camera on me… she is still recording. I have never heard myself cry so deeply, or be touched by something that someone left behind. A painting never did that to me. It was like her touch. It was her art. And I think about how our ancestors are still recording us! They are not just helping us, they are documenting us, you know? They dabble, too!

TH: What an incredible archive to have.

EHS: Talk about archives! You love archives! I would love to show you sometime everything she has left behind. It must be like a hundred videos and fifteen notebooks. She just documented everything! What a gift! It was a really transformative time. And when I was working with kids, I thought about how Aunt Christina was looking at me when I was young. I was in her love gaze. If I would have gone off to grad school, I would have possibly never found those chests in my life.

TH: You don’t think you would have found them?

ESH: Maybe. But I’m happy I took the time to go find myself instead of trying to go succeed in the world right away.

TH: The ability to hear yourself without the static of everything else is not easy, and that’s a hard thing to get when you’re in environments that are pushing at you, imposing on you, and asking for your attention. So, when you did come back to making work, was there a shift in your relationship to abstraction?

ESH: Yes, and it definitely came after the farm. I started wanting to put myself into the pieces. I was thinking about how my body or a form could fit into something that looked abstract. I really wanted to get back to painting things like the [title] painting that was solely abstract but looked figurative. I wanted something that was more symbolic to the body. After the farm pieces were done—just like the farm—I came to a moment where I knew I was done. I realized the [presence] of the body was complicating the field for me—the body didn’t need to be there anymore because it was becoming too narrative. And, at the time, in my spiritual practice I was in a space where I was negating my body, in a way. I was surrendering it. Then, I got more into the body presses and folded pieces.

Also, the flooring, for me, isn’t just a material. It’s an arena. It reminds me of being in my grandma’s kitchen. It reminds me of gazing down at the floor while I’d listen to my grandma, aunts, and uncle talking. I would look at the floor and see faces in the lines and chips of the flooring. [The floor] was a place for me to imagine. And because I was in the city, I was missing home. I’m always missing home. Using the flooring made me feel [at] home. Then, to press myself onto it made me feel like I was really connecting with myself, my family, my childhood, and parts of me at play—back to searching in the mud for potatoes at the farm.

TH: Was there other work or moments of research or information intake that came before this work?

ESH: Yes, I was working with a lot of liquid and transparent materials. I was using makeup brushes because that’s all I could afford at the time. I was also doing a lot of automatic writing, which was perfect for after the farm. I wanted to experience things that were automatic. I also took remote viewing classes with an ex-CIA agent. It was about connecting with things remotely and beyond. [This agent] was known for being able to find where an object was using [this method]. It also requires a certain kind of breathing technique, building your chakra system, and finding focal energies and points.

TH: What?!

ESH: It was really interesting to me. I remember being in my mother’s kitchen—she was making tortillas, and I was trying to explain to her what I was doing. [laughs] I have a lot of sketches from that time [that I’ve thought about making into paintings]—and that was when I found the [form of the] body in the work. Automatic writing and remote viewing helped me think of the body within a much larger scope and macro image. This all [contributed to] the lore or mythology in my head.

TH: That brings you to the work you did earlier this year—Lore at Tiger Strikes Asteroid.

ESH: That work came into fruition when I realized that my name spelled ‘lore’ when reversed, and I was in a state where I wanted to tell stories with abstraction.

TH: What are you currently consuming and reading? What would be in the bibliography of right now, for you?

ESH: I’m listening to a lot of Tony Anderson, who makes movie scores. And Max Richter. Also miscellaneous ratchet playlists. I’m reading a lot of poetry—“Blessing the Boats” by Lucille Clifton. I’ve been reading “The Artist’s House” [by Kirsty Bell]. I’ve been doing a lot of listening—and playing my cello, writing music. These are helping me kiss my fears goodbye.

TH: I usually wouldn’t ask a question like this, but I’m genuinely curious after hearing about this experience going through your aunt’s materials. If you could speak to your teenage self, what would you say?

ESH: I would say, “keep your head up, keep your heart strong.” I would say that it’s okay to flush things away. I would also say quit mixing liquor and weed! It’s not the painting elixir! [laughs]

TH: Practical advice!

ESH: And I would say, “Just have fun because you’ll be in this forever. Maybe not in this body, but you’re infinite. Don’t be afraid. There’s plenty of time. If you don’t get it now, you’ll get it at another time, in another space, in another incarnation. There’s nothing you don’t have. And the rest will just happen.” That’s basically what Aunt Christina told me.

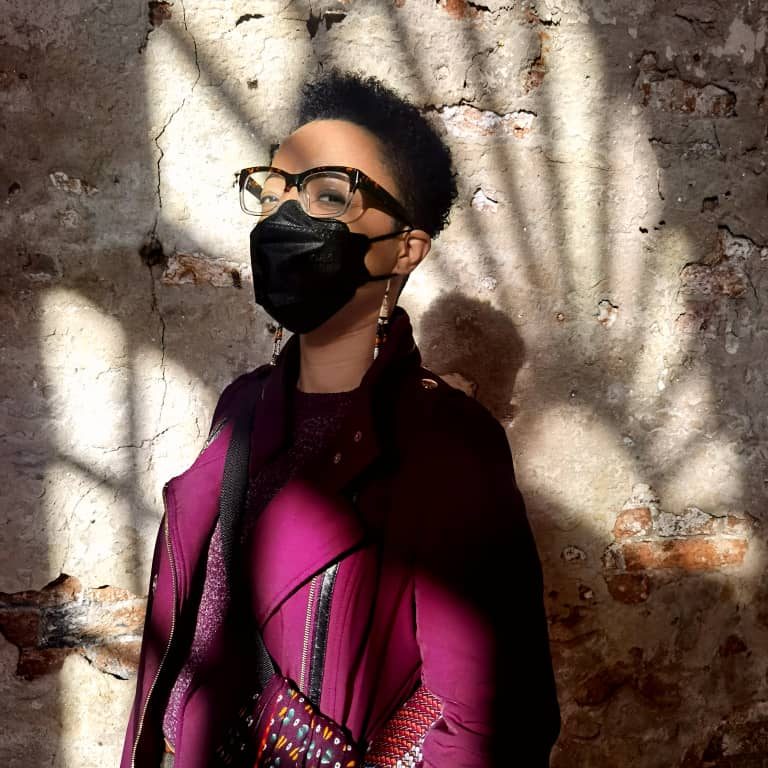

About the Author: Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. She spends her time working alongside artists, organizers, grantmakers, and cultural workers to explore solidarity economies, cooperative models, archival practice, and systems change in and through the arts. You can see more of her editorial, curatorial, and other projects at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Chaka B. Wallace.

About the Photographer: Ryan Edmund Thiel (they/he) is an artist, photographer, and graphic designer living in Chicago. Their work across media explores healing, liberation, and empowerment for the individual and collective. Their mission is to support artists and organizations whose values align with care, social justice, and collective organizing. Ryan is also the lead graphic designer for Sixty Inches From Center and co-lead of Sixty Collective. View their work at ryanedmundthiel.com and @talldarkandryan on Instagram.