“This is how Guantanamo treated art, Guantanamo art is a living being. He is one of us. It is a part of Guantanamo. We had it, we hid it, we fought for it. And it was treated like us. it will be searched, it will go before commission like us going [in] front of PRB [Periodic Review Board, if you are clear, you can go out [of] Guantanamo now.If I’m not clear, stay there. Some of the art died at Guantanamo, sentenced to death, like our brothers at Guantanamo. And among [it] some of us managed to make it out.”

Mansoor Adayfi

My dad would always take the longest time to make his tea. If he was to drink tea, it was brewed on the stove for at least 15 minutes. Sometimes, entire conversations would happen and we would ask, is the chai done yet… only to hear him say, not yet, be patient.

Upon entering Remaking the Exceptional at the Depaul Art Museum, the first thing I noticed was the tea setup: an assortment of spices — cardamom, clove, saffron, turmeric, cumin, and some I’ve never heard of; tea bags and a grand steel percolator. Majestic… despite the context of violence it’s placed in. The room envelops you. The quiet sounds of a scratchy radio and the walls covered with images of flowers, and tea, hanging ceramic cups.

Recently at my family dinner, we were talking about the nature of tea: you never make it for just yourself. You always ask, does anyone else want some? Make the rounds. And if we want some, if we all have time, we will break our routine and sit for some chai.

Tea was central here: paintings, ceramics, spices, trays, and a percolator all devoted to it. A yearning for those communal moments — of leisure and luxury — were so clearly apparent. In a featured painting by Guantanamo detainee Ahmed Badr-Rabbani, the depiction of a long table, royal blue all around… and empty chairs, the moment ready for a grand celebration. Chandeliers lining the walls — lights all across the room, homes and vibrancy — it reminds me of Morocco at night.

The paintings were created and grouped by themes: ships, tea, trees, and the sea, all referencing a different aspect of yearning. Longing for those intimate spaces shared over tea with loved ones. As Mansoor Adayfi puts it, “The art holds time, pieces of our lives, memories, loves, pains, hopes, longings, dreams, fears, and joys.” That is to say, the expansive imagination attempting to close distance for those folks detained.

Tea is both a medicine and a culture, both intimate and alienating as a product that transgressed borders — I think of the British East India Company. This implicit connection between the E.I.C. and the U.S. Military is manifested in the form of the ‘torture tree,’ a conceptual map of interrelated violence, represented here by wooden planks (almost like a pier) upon which are an arrangement of maps, as well as a tree branch with tendrils connecting those maps of colonial violence, and a staticky radio. Buried in the muffled sounds of this radio, pulled from the sea, are the stories of Chicago Police Officer Jon Burge and his electric shock device, drawing the lines on this map of political power back to Chicago. The room it is in is both spacious and empty, eerie and warm.

What does it mean to use tea as this means of connection — drawing the lines of violence from one part of the globe to another as though violence and tenderness are seated next to each other?

To unpack some of this artwork, I set up an interview with one of the artists in the exhibit, Mansoor Adayfi, who was formerly detained at Guantanamo Bay, though he’s now a writer located in Serbia. What he revealed was the tenderness of the pieces, and the harshness of the environment in which they were created.

I started our conversation with an “Eid Mubarak,” and he responded with a resounding “Asalamoalaik Wa-Rahmatullahi Wabarakat” meaning, “Peace be upon you and God’s mercy and blessings.” He reminded me of some of my favorite uncles, hearty with their laughs and their proclamations to God. The conversation felt as though we were sharing a cup of tea, but instead he promised a plate of biryani that I know we will never be able to share. We joked about my grandmother’s biryani and he sent me the warmest wish along with it: “I love her so much for bringing your mother into this world who brought you to write this story.”

The story of how art left Guantanamo is a reflection of how the people were seen and treated in detainment. Each piece, with every draft, was created in a system of violence. Under President Barack Obama, Guantanamo introduced prison art classes in 2009, but with harsh restrictions — the artists chained with limited time to create and their art was frequently destroyed by guards without explanation or justification.

All of the art referenced a freedom that individuals long for while detained: freedom to share intimate space — like tea; freedom to imagine expansiveness— like the sea. In his book, “Don’t Forget Us Here,” Adayfi talks more about this, describing the beginning of art on the island:

“From the beginning of Camp X-Ray, we had been creating, and those small acts were our escape. Some of us wrote on Styrofoam cups and plates. We used spoons or twisted the tiny stems off apples to write poems or draw flowers, hearts, the moon. We made flowers out of stickers we found on fruit. These were tiny expressions of our former selves breaking through, resisting the identities imprinted on us. These simple expressions were as necessary as food and water, and they were always punished. Even an etching of a flower was not a flower; it was a message to Osama bin Laden and a national security threat. For years, it was a game we played with the camp admin. We took nothing and made something, and what is more human than that? In turn, they took whatever we made and punished us to prove that we weren’t.”

The inscriptions on styrofoam cups made by detainees inspired the ceramic cups produced by Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg, titled the Tea Project, intended to signify every different population represented at Guantanamo. Each styrofoam cup was engraved with the national flower from a detainee’s nation of origin, and the amount of flowers represented the number of people present from that country at Guantanamo Bay. There was beauty in the diversity of flowers… but violence as well in the sheer amount of flowers on each cup.

Of the 780 cups, 48 different countries of origin were represented; people from all around the world were captured. Each ceramic was cast from a mold and inscribed with flowers, a repetitive process representing the volume of people detained without making individuals into statistics or graphs. To archive this history onto a medium like ceramics is to say that it will never be erased, that these may be buried in the land and will live long beyond the lives of the people they represent and tell their story.

These cups, each signifying the vastly different culture that an individual brought with them represented “a small piece of fabric woven together with threads from all over the world” as Mansoor puts it. . Whether it be the henna staining their hair, or the dances they shared, people like Mansoor resisted through their art, and tried to maintain memories of their homelands by sharing their art.

These cups reminded me of my own ceramics work, the care that goes into making each piece: the first step of imagining what it may look like, the finger prints ingrained into the work, the way porcelain glides and slides so easily. Porcelain — a commodity so valued in a history of capitalism and colonialism— used to signify such an ugly history of American violence, but here the beauty of the ceramics honors the lives lived and lost at Guantanamo. Creating one piece is already so arduous and creating identical pieces is incredibly hard. These ceramic-styrofoam cups reminded me of how Mansoor described Guantanamo as a “lab” where the American government wanted to create something from these people, something uniform, to fit them into a box. But to resist that narrative and demonstrate the diversity among detainees, the flowers show their beauty.

When I look up from the ceramic cups, I see Dorothy Burge’s quilts hanging from the ceiling, portraits of John Burge’s victims (no relation). Made with the most vibrant colors — somebody’s skin as bright red, green thread outlining someone’s cheek bones — it catches my eyes immediately. No matter whom, the richness with which one’s face is displayed gives homage emphasizing their beauty, in stark contrast to the images of torture throughout the exhibit. Quilting, an ancient practice, reminds me of grandmothers, creating blankets from what is left over, creating beauty from different pieces. I picture Burge, sitting stitching the wrinkles of someone’s face… this is nothing but an act of care. To honor someone’s life despite the violence they were victim to. As Dorothy says, “I saw [making quilts] as a way to keep this issue alive, and also a way to advocate for the people who are still incarcerated who have been tortured by Jon Burge.”

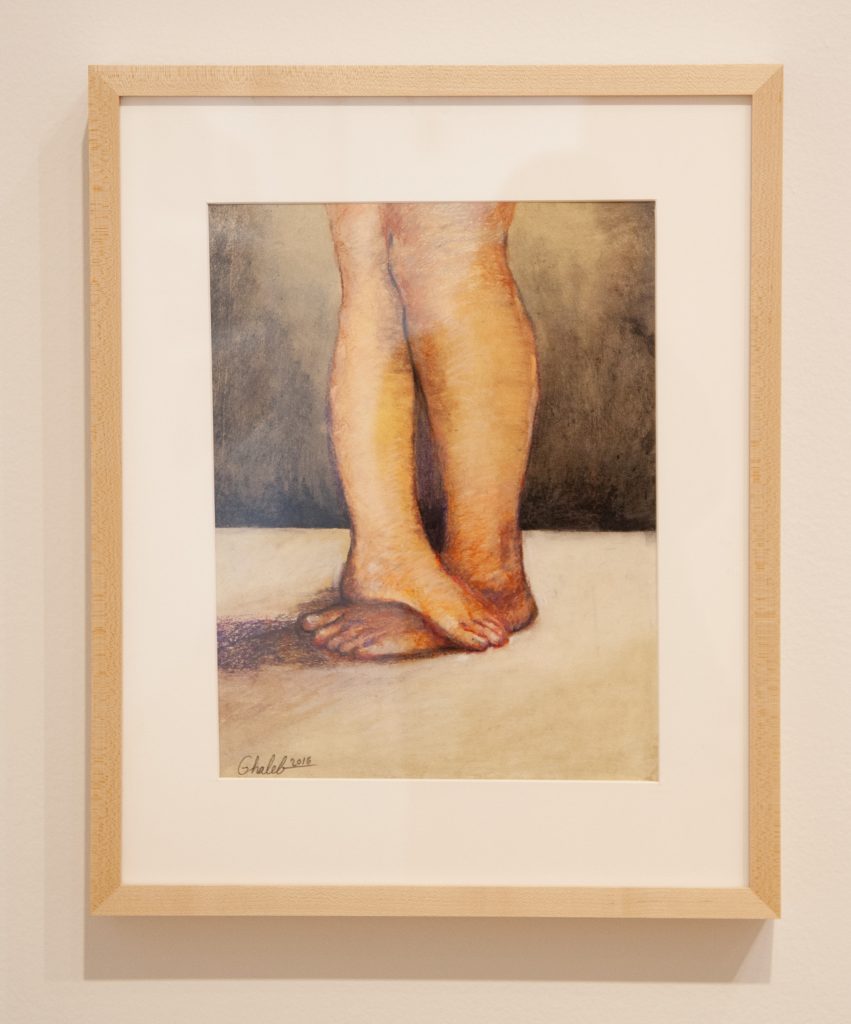

Just as Burge’s quilts evoke a closeness, a piece in the exhibit by Ghaleb al-Bihani, labeled Untitled (2016), portrayed a certain intimacy. This piece features two feet, one resting above the other. This closeness reminds me of giving someone a hug, movies where the girl stands on the boy’s feet to learn how to dance. One of the legs looking more effeminate than the other, shadows of these legs, creases and shading. The way the knees fit together like puzzle pieces. As Mansoor said, the artwork was a commemoration, preserving a past life, yearning for a future. People used it to remember a time filled with this closeness and love. This painting feels like someone remembering — the love of their life, or their children, or their mother. A clear memory that stayed with someone, while the U.S. Army stamped on their back.

Being here, I wanted to grab someone’s hand near me, seek people and joy. A few weeks before the exhibit closed, I took my mom to see it. We planned a day around it and I walked her through the exhibit, tying together the stories and explaining the art in a way I hoped she would understand. The language of violence — academically spoken — wasn’t needed. Walking back to the car she repeated to me what my grandmother used to say all the time — this country exports violence to places all over the world and now it is rotting from within.

As Dylan Rodriguez explains, prisons are not just the four barbed wire walls outside of a building, but the prison regime: something with tentacles expanding across the globe. These spaces, Guantanamo Bay and CPD torture sites like Homan Square, are a part of the state exercising what Foucault describes as “biopower,” essentially the right to “make” live and “let die”. They determine the horrendous conditions of life and death— making it impossible for people to remember a time outside of that.

This art is, in a sense, a plea to remember life outside the state, regardless of the state. To preserve moments I shared with my family, over cups of tea in our kitchen, sips when I was much too young for caffeine. This art yearns to remember the closeness of sitting near those we love, and maybe those we don’t, and sharing the warmth of tea in the hottest of summers.

But the state looms. As Mansoor stated in the middle of our interview:

“When you arrive at Guantanamo as a young fresh teenager, Isra — and the moment you arrive, you’ll never be the same person.”

And then there was a long pause in our conversation.

You can find out more about Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg’s Tea Project here. If you’d like to read Mansoor Adayfi’s book, “Don’t Forget Us Here,” you can find it available to purchase here.

About the Author: Isra Rahman (she/her) is a freelance journalist and legal advocate based in Chicago. Her primary work involves police misconduct research in downstate IL which she does with the Invisible Institute. She is a former fellow of City Bureau covering food apartheid on the west side. Through her art and writing she hopes to explore grief, care, and resistance.