“If I didn’t define myself I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies of me and I would be eaten alive.”

– Audre Lorde

THICK begins in the lobby of The Dance Center at Columbia College Chicago on the weekend of March 14th, 2025. We are approached by our hosts for the evening with a warm greeting, kind smile, and told the space of THICK is a place where cash can flow. This is the time to change our virtual cash into physical bills.

What is THICK? Perhaps: an architecture, a construction with crevasses, corners and caryatids of Black women; perhaps: a freak show in reverse, a funhouse mirror, a ritual for not forgetting.

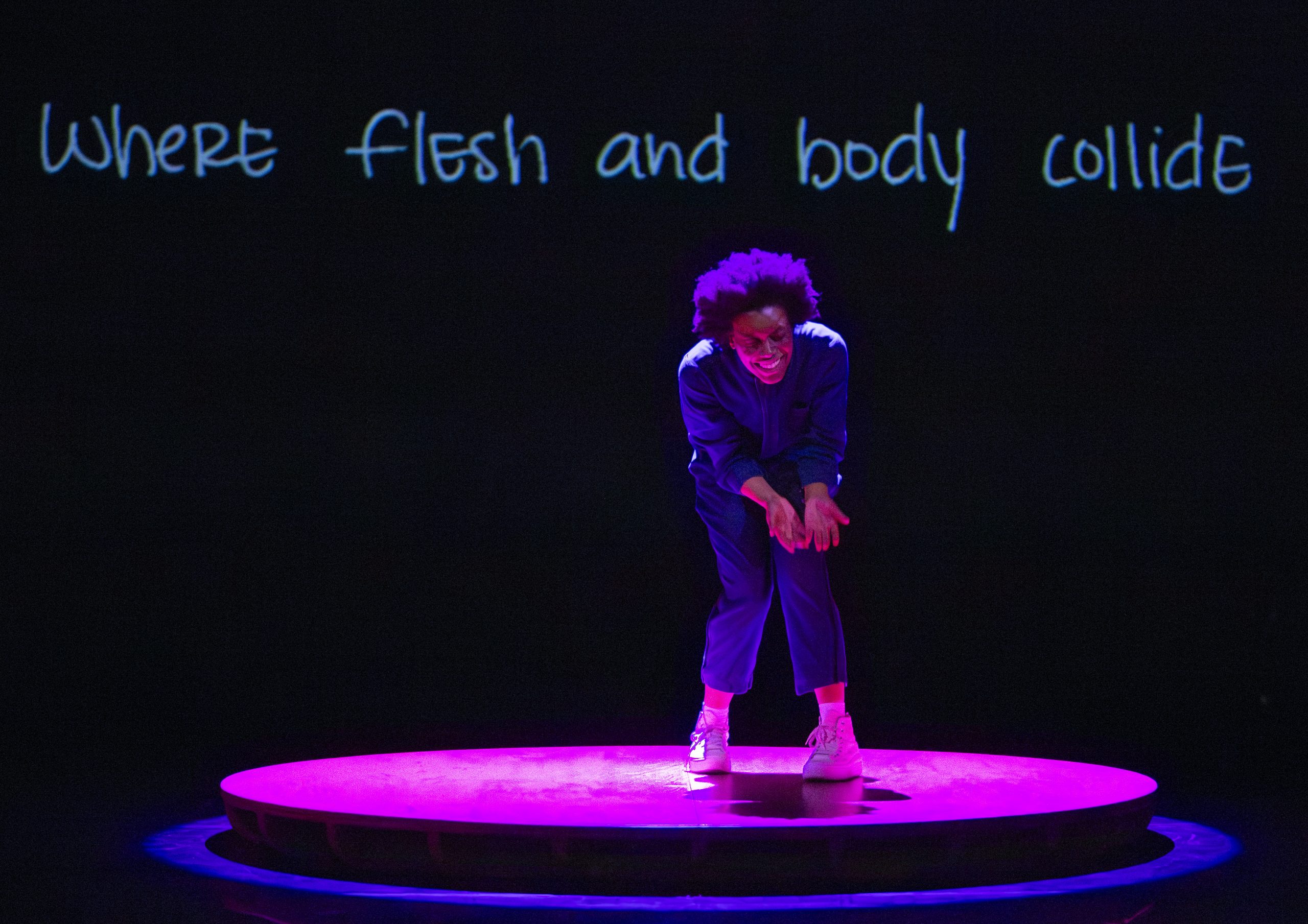

We walk into the theater through the stage door. There are chairs and floor cushions placed directly on the stage and a crumbling circus tent suspended from the ceiling and a circular platform at the stage’s center. Meditative sounds play while we settle and Jenn Freeman | Po’Chop enters. They perform a quiet ceremony with vessels of water. It’s not a moment that pulls attention, but rather lets the performance start with a whisper.

Like a seance, we watch as a secret space of held remnants—breath, prayers, fingerprints, and time—is conjured onto water, memory, glass and Freeman | Po’Chop. Like the lifting of fog—when the water’s edge is just becoming clear, it was at this moment we all knew THICK was starting, that is, if it hadn’t already started, long ago.

The next hour or so of performance is a tour de force of Freeman | Po’Chop’s chops. They easefully move and speak urgently. They twerk and shake. They glide from drag to performance art to dance and back. In one striking moment, they lip-sync a genocidal set of instructions on how to co-opt and erase a language. Just before, we watch their shadow change clothes, silhouetted against the white and red curtain of the circus tent.

In another moment, a duet plays out between Freeman | Po’Chop and a small moving rectangle of yellow light. Po’ wears a fluffy layered dress , dancing mostly in the shadows while the grotesque yellow neon darts over and past them, up the walls and ceiling, and around the stage. When the yellow happens across Po’, the stage is suddenly illuminated with the ricocheting reflections of the dress. Even in this game of light and dark—our eyes are fixed. They hold our gaze and offer their own back.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

“This is one reason why the erotic is so feared, and so often relegated to the bedroom alone, when it is recognized at all. For once we begin to feel deeply all the aspects of our lives, we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life-pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of.

Our erotic knowledge empowers us, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence, forcing us to evaluate those aspects honestly in terms of their relative meaning within our lives. And this is a grave responsibility, projected from within each of us, not to settle for the convenient, the shoddy, the conventionally expected, nor the merely safe.”

– Audre Lorde

The word erotic is often feared and associated with the taboo: don’t speak it, don’t think it, don’t think about it. But here, just like in THICK, Lorde offers us the imperative: words like demand, capable, honesty, responsibility, and to not settle. Freeman | Po’Chop’s work and practice are a consistent nod to Audre Lorde. The cover of THICK’s accompanying zine quotes Lorde directly.

Rachel Lindsay confesses to Freeman | Po’Chop about a moment during THICK that they write “this work doesn’t feel about the erotic”, realizing that maybe there is still work to be done in deconstructing their view of the erotic. Freeman | Po’Chop agrees, replying: “I would dare say that you described the erotic when you were talking about the last moment with the pork chop, the sound and all the textures.”

Towards the end of, THICK, the lights come up, illuminating the buttery soft, circular stage. Freeman | Po’Chop carries an ironing board table to the center, places a red and white gingham apron, ties it around their waist and begins dancing with a cast iron pan—a tribute to dancer and choreographer Blondell Cummings. Their movements are decisive: exact and intentional in a way that holds our eyes to every facial expression, every arm sway, every hip and leg bend. We feel the weight of the skillet, we are eating out of their hand. It is a moment of expectation and transfixing tension.

Freeman | Po’Chop’s dance shifts when they return to the platform, placing the skillet on a small stove atop the ironing board. Turning it on, the pan begins to heat. They waterfall a big glug of cooking oil into its basin, unwrap a literal pork chop from brown paper and rain salt down upon it. They raise the meat from the butcher paper into the air and transfer it to the now-smoking and sizzling pan.

The effect is one of incredulity. The smoke! The pan! So much oil! Will the smoke alarm go off? Wait, is it cooked? Did they cook it all the way through? Did they flip it? I don’t remember seeing you flip it…they flipped it, they must have flipped it…its pork…did they cook it long enough?

That level of density, of textures—internal anxieties, but also literal textures—felt like the waft of smoke coming from a pan, filling the room and ourselves. We initially thought this was just a bit, a gesture, a reference to something, but when Freeman | Po’Chop picks up the pork from the pan, it is literally dripping. We are going all the way. Dare we say it is erotic.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

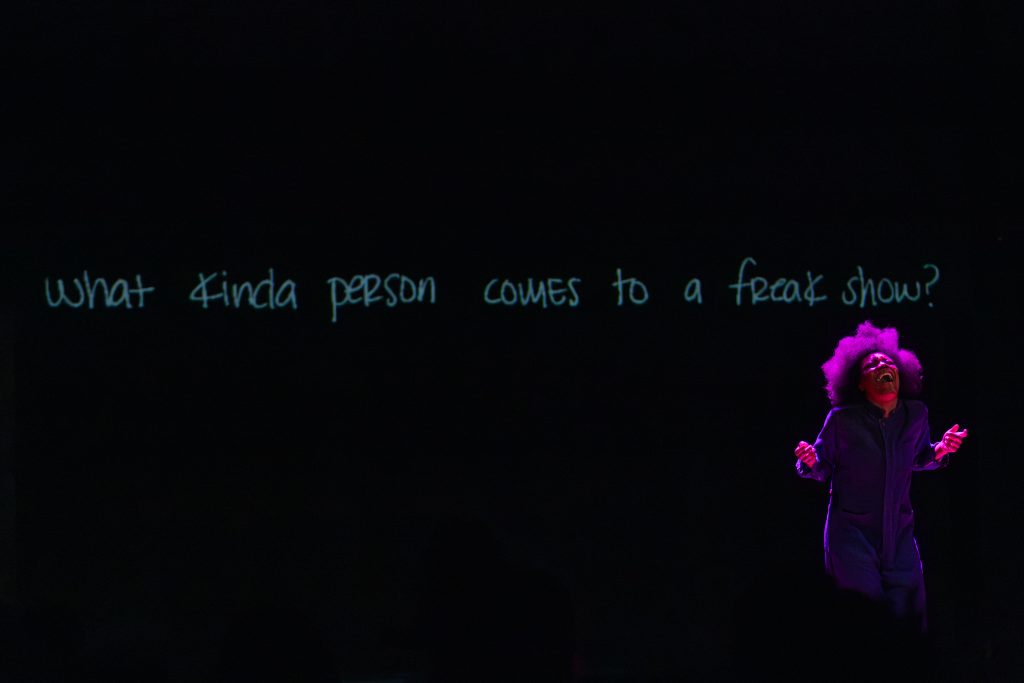

One of the principal tensions of the performance is invoked by Freeman | Po’Chop at the beginning: “What kind of person comes to a freak show?”

This is the question we oscillate around as an audience. We came to the show, we are implicated in it. We look and we give Freeman | Po’Chop power. They look back and give us something in return—some words, some physicality, some entertainment, the smell of a pork chop cooking. This is the dance of the work, more so than anything physical. It’s a social thing—the motion of power from performer to audience to performer. From ancestor to present and back again.

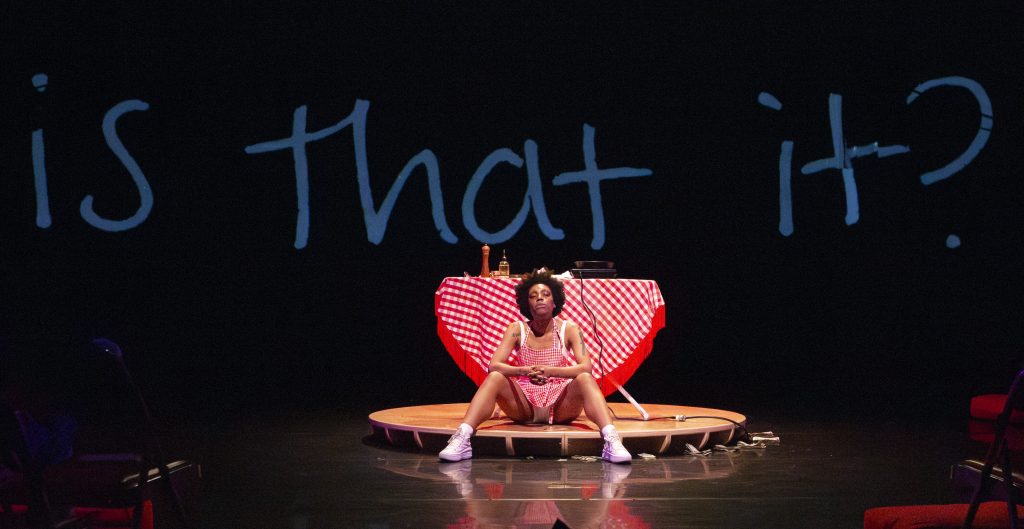

Ssehura is one of the ancestors that Freeman | Po’Chop summons. She has another name in the historical record, but THICK does not speak this name—a name given to her by oppressors. Instead of a history lesson (a repetition of the violence of the story), THICK is an invitation to sit without story for a moment. When you look in the archive for evidence, its polyphony is both overwhelming and obviously incomplete. What happened? Is that it?

Back on the stage, power materializes in the form of the dollar bill. Freeman | Po’Chop invites us to throw crumpled dollars as a marker of gratitude, engagement, being taken by the show. The instructions are simple: offer a dollar you don’t need and say, “Is that it?” They ask for $18.70 from the audience. Ssehura’s remains were held for 187 years in Paris before finally being repatriated to Hankey, South Africa in 2002. Is that it?

THICK wrestles with these poles of consumption, capital, and reclamation. There is consumption present in entertainment: it is a show that we paid money to attend. There is consumption present in the form of the freakshow—the bodies on a stage, in a tent, spotlighted and draped in sound. And then there is consumption of food: a sandwich is literally made on stage. That sandwich is then eaten, in silence, on stage. This is not fiction. We watch them eat in silence. We throw more money. They continue to chew.

When asked about this moment, Freeman | Po’Chop says: “[There is] Ssehura but also all these other Black women who experienced extreme violence that we will never know about, and also never know their names or their specific stories, or their favorite colors or their favorite smells….I feel like at that moment, that is what I am kind of thinking about. And the only thing I know to do is to claim myself, to claim my body, to care for myself, and to also enjoy—in some ways—consuming myself.”

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

“IS THAT IT?” continues to flash large on the back wall . This chorus haunts the project of THICK—“is that it?” Freeman | Po’Chop offers the work as a small form of redress, reparations, some ways of honoring both their personal history and a greater, collective history.

After Freeman | Po’Chop finishes eating the pork sandwich, they then leave the room in silence. It is an inversion of the Freak Show—a group of people staring at an empty stage, and we all remain there—transfixed. It is incredibly awkward and entirely perfect. We can’t bear to break out of the silence, it would mean it would be over, it would mean the spell would be broken.

An echo from the beginning: “What kind of person would come to a freak show?” The empty stage has now become a mirror and we are left with only ourselves and also an absence. Yet, just like the water jars from THICK’s opening: the stage is not empty—it is still teeming with whispers. Freeman | Po’Chop describes THICK as “ancestor work” and their process of looking back into the archives as a way to breathe into its gaps.

Is that it? Is an hour-long performance anywhere close to enough? It takes a long time before the crowd finally releases into a standing ovation, but Freeman | Po’Chop is long since gone. We applaud the gap on the stage. The projected words “IS THAT IT?” still on the wall. The projection upsettingly, persistently, demands more. THICK points to where the gaps are and demands more light to fill them. Even if we have to make it up, even if we have to release into not knowing, even if we have to applaud that gap.

…

Thick Cast & Crew (in order of mention)

1. Cash girls: Shimmy La Roux and Hoochie Mane

2. constructed by Erica Gressman

3. constructed by Frey Michael Austin

4. Sound design by Jamila Woods

5. Garment by Veronica Sheaffer

6. Lighting by Christine Shallenberg

7. Projections and captions by Ruby Que

About the author: Corey Smith is a composer, writer, and performer from Chicago. They love the Great Lakes and teach at the School of the Art Institute.

About the author: Rachel Lindsay is a Chicago-based artist and writer working in performance, installation, drawing, poetry, memoir, and essay. They received an MFA from UIUC in Visual Arts, with a graduate minor in Dance in 2020. They are a Luminarts Fellow with select solo shows at Krannert Art Museum, Swedish Covenant Hospital, North Park University, and The Front Gallery New Orleans. They are a member of Conscious Writers Collective and Out of Site Artist Collective.