This is the fifth in a series of articles made in collaboration with the Chicago Arts Census to explore the living, labor, and material realities of art workers in the city of Chicago. Click here to read the other articles in this series. Please visit the Chicago Arts Census website to learn more about the Census and how to get involved.

The Personal is Political, and the Political Will Knock Your Teeth Out

I never saw the final episode of M*A*S*H, except I probably did, in sonic proximity to a console color television contained by a palm-fronded, wicker-dominant room for “families” and “programming,” which also held most of my childhood. Channel Up, Channel Down. I have no memory of the event, but I recently read that, short of future broadcasts involving a “kick-off,” the 4077th’s last hurrah — “Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen” — set against the closing days of the Korean War, will likely remain network television’s excelsior event, a watershed shared-witnessing of scripted content and midlife swan song for a particularly media-stricken and never-to-be-repeated age of American seriality. February 28, 1983, was a Monday. I was two-and-a-half years old. Childhood milestones around 30 months include the ability to state and understand pronouns, to name things when pointed to and asked, “What is this?,” and to say around 50 words, yet I was somehow — against all socioeconomic and genetic odds — emphatically and precociously verbal. At my first birthday, I greeted attendees with, “Welcome [to] party — Happy birthday to me!” This is a watered-down ask about who trained me to parrot what, and why, but also a question begging more complex structures of politics and feeling, internalized by those privileged to hear and speak against the cacophonous din of the late-postwar era’s turn to industrial deregulation and oversaturated consumerism, in the anxiety-riddled moments before the human voices woke us, and — too little to clap on, too late to clap off — we drowned.

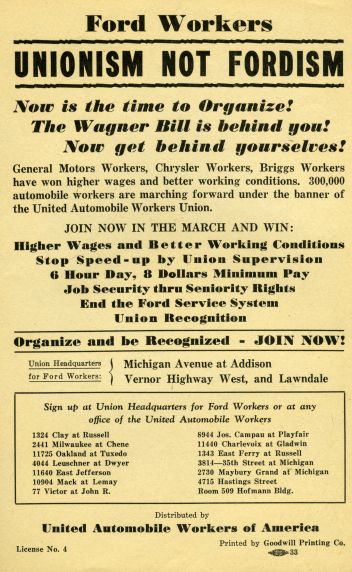

I grew up in the post-industrial Detroit suburbs in the early 1980s; my mom was a middle school teacher and union member for the entirety of her career, apolitical but loyal to the importance of public education. My paternal grandmother worked at a factory that produced radiator parts and heat-transfer devices for heavy construction equipment. Once, I sat with her on lawn chairs near the picket line, drinking a glass-bottled Pepsi; later, when I was in junior high, our band teacher’s son died of chemical exposure while cleaning out one of the degreasing tanks inside. My dad’s step-father was a Korean War vet, SFC, of whom I remember little, let alone his vocation, in those years so long after the war. I saw him sometimes shirtless, save for a tool-and-die-maker branded coat, missing some teeth, and my burgeoning class consciousness didn’t do much to overcome a childhood fear of older men and a preternatural understanding of soft power. I bear his last name; that’s probably enough. My mom’s mother sold bras and then BBQ grills at Sears, and my grandfather was a switchboard operator at Detroit Edison. No one belonged to a union, except maybe they did, but I do remember the parents of neighborhood playmates in foul-tempered moods after lay-offs from steel manufactories or lumber yards or automobile factories, like the Ford Rouge (Dearborn) Plant — home to both the Mustang, and the notorious union-busting “Battle of the Overpass” (1937), in which Henry Ford’s private security forces clashed with would-be UAW workers, captured on camera by a journalist who hid the photographic plates under the front seat of their car. Their eventual publication — along with Ford’s well-publicized bigotry and anti-Semitism — helped shift public sentiment against him, and facilitated a UAW contract just three years later, while the skirmish between union members and Ford’s toughs was commemorated in Upton Sinclair’s experimental historical novel, The Flivver King: A Story of Ford-America. Anyhow: M*A*S*H is a show about the tragicomedy of historical circumstance, the greedy ravages of imperial capitalism, zingers about hating your job, nurses showering in tents, and also how steam rises so expediently from a man’s chest, once you slice it open in the cold air, that it can heat someone else’s body, which is a crude way of saying: it’s mostly about empathy.

Shortly before my family moved, in the middle of my third-grade year, one best playmate of mine let another best playmate belly-ride his skateboard down the curb. The rider lost a tooth. His dad was so pissed that we were never allowed to play together again. He had recently lost his job. This was a summer’s day sometime after the Michigan wildcat strikes (1986), set off by the uncouth firing of a United Steelworkers vice-grievance chairman, and before McLouth, an integrated steel company recently bought out by a Chicago industrial raider named Tang, would go on to become 85 percent worker-owned, part of a collective bargaining agreement that saw wages and benefits cut by ten percent in return for three seats on the Board, and a gainsharing cooperative partnership helmed by the union local (1989). But you can only save a steel plant for so long, as Woody Guthrie mostly sang in “Pittsburgh.” Bruce Springsteen’s first band was called Steel Mill, and Philip Levine’s “What Work Is” was what I memorized at night the first summer I lived on my own, willing myself to break lines like a poet (“You know what work is — if you’re/old enough to read this you know what/work is, although you may not do it.”). My dad went on a disability leave that turned into early retirement, after collateral damage from a major heart attack made it impossible for him to keep a job that taxed his body, and it’s my mother’s union-subsidized health insurance that keeps him alive (“Forget you. This is about waiting/shifting from one foot to another.”) This is all a long-winded way of saying: I do know some things about unions, though once I was small and knew very little, yet strangely enough, I have always known what work is. The tragicomedy of historical circumstance, on the other hand, never escaped me, nor an uneasy familiarity with what remains when the proxy wars are finished, and structures of living and labor come undone. What does it all sound like? A little like the memory of overhearing Hawkeye plant a kiss sloppy with pathos on the cheek of someone called Hot Lips, while the North Korean prisoners of war played the CBS audience off to commercial break with Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto. Or maybe more like a squeal, something akin to the sub-harmonic pitch (15 kHz) of a flyback transformer in the horizontal deflection circuit of a CRT TV, a sound they say only younger people with “good” hearing can register, quite the metaphorical exegesis, by way of explaining the static my generation took in, while sleeping or nursing or half-watching, our bodies not yet fully formed — “Welcome [to] party!” — our lips wet with dissatisfaction in the other room, as close to mouthing something approaching solidarity as we could get.

Interlude

Here are two jokes, procured from a Google Verbatim search:

Q: What’s the difference between an artist and a trash collector?

A: The artist takes out her own trash. The trash collector makes $50,000 a year with sick days, benefits, and a retirement income after thirty years.

Q: What’s the difference between an artist and a pizza?

A: A pizza can feed a family of four.

And here are two more, produced by a GPT-3 AI, part of a research lab co-funded by Elon Musk:

Me: I want you to tell me a joke.

The joke begins, “What’s the difference between an artist and a worker?” What’s the punchline?

AI: The punchline is, “The artist is someone who creates things that didn’t exist before, while the worker is someone who makes things that already exist.”

Me: I want you to tell me a second joke.

The joke begins, “What do an artist and an assembly line have in common?”

What’s the punchline?

AI: The punchline is, “Both of them can produce a lot of crap.”

Terms and Conditions

I’ve spent the past 12 months mostly doing two things.

The first, fulfilling and psychically exhausting, was organizing a union of non-tenure-track faculty, alongside my indefatigably committed colleagues, as part of Art Institute of Chicago Workers United (AICWU). We’ve just filed for our union election with a strong majority of card-signers from the largest possible bargaining unit, and hand-delivered our request for voluntary recognition to SAIC President Elissa Tenny. All of the work that we have done was inspired, strengthened, and at times, co-facilitated by our Staff colleagues at the School and Museum, who voted in their union overwhelmingly this past spring, and are currently at the bargaining table pursuing their fair contract with an imported union-busting attorney from Texas, on AIC’s semi-permanent retainer. AICWU is represented by the American Council of State, Federal, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Council 31, and part of AFSCME’s larger Cultural Workers United movement, which has organized more than 35,000 workers at cultural institutions nationwide, like the Walker, the Met, the Philadelphia Museum of Art (currently on strike — solidarity!), and the American Museum of Natural History.

I’ve participated in efforts to form a union in the past at SAIC, and I’ve been paralyzed by research into the right union representation for contingent art school faculty, many but not all of whom identify primarily as artists or arts workers, and whose flow chart of labor — the majority of it unregulated, under-compensated, and often overlapped into spheres of illegibility — calcifies the Chicago arts community. Choosing to be repped by a union that only organized educators would have been disingenuous to the lived experiences of many of us, and by default, would have further divided us from the Staff colleagues who so eagerly stood beside us, assisted our cause, and showed us the way.

To put this another way, our needs have less to do with the specificity of the artist-run communities we engender and participate in, and more to do with a much larger system — one that marginalizes and oppresses us, against the very best of our interests — we are complicit in perpetuating. We can turn to the work of twentieth-century feminist activists like Silvia Federici, whose Wages against Housework (1975) accounted for unwaged domestic labor as a fundamental manipulation and oppression of the working class, largely women whose “bodies and emotions have all been distorted for a specific function, in a specific function, and then have been thrown back at us as a model to which we should all conform if we want to be accepted.” Or we can push further, to the writings and oratory of Frederick Douglass, whose nineteenth-century abolitionist labor activism spoke against the dehumanization involved in robbing people — and their labor — of worth and value, and who reminded us in his address on West Indian emancipation (1857), “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never has and it never will.” We should insist upon that shared stakes that inform Dolores Huerta asking of farmworkers’ labor, “Why is it that the people who do the most sacred work in our nation are the most oppressed, the most exploited?,” and the work of the anonymous contributors to W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy, a project premised on the promotion of self-regulation, collectivity, and equity, to “organize an unpaid workforce in an unregulated field”), who call out, in the hopes of remunerating, the art world’s boundless reliance on illegible unpaid labor. Huerta’s ask is amplified by the work and legacy of the Chicago Teachers Union; by Chris Smalls and the Congress of Essential Workers/Amazon Labor Union, first organized during the pandemic, on the heels of Smalls’ unlawful termination from a Staten Island warehouse, following an employee walkout over the absence of COVID-19 safety protocols; and by frontline railroad workers preparing to strike after an “efficiency push” made their working conditions untenable. The stakes are shared, and so is our struggle: workers’ rights are immigrant rights; they are the rights of people of color; they are the rights of those with disabilities, and the rights of those who identify as queer or trans or non-binary; they are women’s rights; they are indigenous rights. They are afforded to us because we are people obligated and ennobled by the right to self-determination, whose humanity is intrinsic only because it is shared; these rights are afforded to our labor, because like us, that labor is dignified by worth and purpose.

As a teaching artist, my practice involves insisting upon critique as harm reduction and a process of articulating something real, by which I mean, shared. That’s a fancy way to say I think, with other people, often performatively and beyond conventional genres, and insist upon the importance of such: not only to change the exclusionary identity we attach to thought, but also to center it as the practice through which we rehearse our social and political relations with the world. I’ve never taught a class that didn’t excavate and carefully consider issues of labor, and I espouse all this not to prove my worth, but to preface what I’m about to say by letting you know it’s not my first time at the rodeo. I am personally affronted that many of my best friends do the same work that I do without access to health insurance or greater institutional stability. I’m rageful about a structurally endemic lack of vision, accountability, and moral imagination from those who hold the purse-strings and the power at institutions of higher education, and the laissez-faire neoliberal austerity jumper cables they pull out for each fresh crisis. It’s disheartening to see many of my most brilliant non-tenure-track colleagues, especially my BIPOC colleagues, “quietly quit,” or move on from SAIC to another institution (or an entirely different career), as the administration continues to advocate for “diversity” and call for a better faculty balance, all the while refuting pathways to full-time conversion or adjunct promotion. If one more person calls us “naïve,” or “very articulate,” or tells one of my colleagues that they’re “lucky to teach here,” I will throw a live wire into a bathtub filled with La Croix. I feel embarrassed by the fatigue I showed my students this past year, and though I don’t need anyone to remind me of my worth, my ability, the amount I owe on my student loans, or the indelible mark I — along with so many others — have left on this institution, I can’t help but feel the discomforting weight of inequitable circumstance. When the amount of labor required to earn a slimmer fraction’s worth of my colleagues’ income and stability disintegrated the singular experience of courses I cherished — and protected, as I would any living part of my practice — into something resembling pulled mental taffy, comprised of burnout, chronic exhaustion, and emotional strain, I knew it could not continue. As the story goes with AICWU, “We got angry, and we got organized.”

We also never looked back.

In addition to organizing, much of my time this past year was spent exploring machine learning platforms and neural networks that train AI on natural language processing. You know, sometimes, when you hear two jokes in the same Reddit thread, and you forever mix up the punchlines? (Alternate example: for years in early childhood, I confused Jack Tripper, a character from Three’s Company, with Jack the Ripper, a serial murderer from Unsolved Mysteries.) Union organizing and machine learning overlay in my brain. Both engage labor at its most meta and material levels, and both would employ the logic of commodity fetishism to force our hand: there’s simply no magic hoo-ha or intrinsic intelligence jammed deep inside the things we value — a gently used Honda Civic, a functional laptop, second-shelf Mezcal, or teaching an AI to sing the lesser-known third verse of Dolly Parton’s canonical “take this job and shove it” anthem. That we even desire any of this stuff to begin with — and that desire is subject to change — bluntly occurs because one can read the room, at any given moment, attentive to how each of us organizes our entire lives around the roles we play in a system that has failed us, and whose sustenance rests on our further cooperation.

The first step in joining a union might be signing up for the Signal chat, but move number two is the realization that if the people who perpetuate things as they are collectively stopped complying, a different set of social relations could be produced. First came the emoji, and then the guillotine, remember? Class consciousness is a powerful strategic tool, but less so when it happens in a vacuum. You can’t train an AI to perform anything resembling intelligence with one dude in a basement inputting his feelings about mid-’90s MTV anime, mostly because you can’t have mid-’90s MTV anime without the complicity of many other people, enjambed in networked relations — you can’t even have the idea of the dude. My own social self-understanding wouldn’t exist were I not brought into the light of the cold classist truth by my interrelation to others, and my ability to share my awareness — to cut through my exploitation with a butter knife, to demonstrate our disposability all the more clearly — requires those others to see in my alienation a reflection of their own. Or at least to acknowledge a web of complexity in which they too are, with ever-so-slight variance of the odds, faced with a decision about whether or not to further distract themselves with the spectacle of their own entrapment. Remember when Adelaide starts whistling the folk song, “Itsy Bitsy Spider,” in Jordan Peele’s Us, seated in front of a hall of mirrors, and then Red, her doppelgänger, picks up the next note? Yeah.

Your Average Electrician

Reader, I include this interlude because — though class consciousness clearly informs my joie de vivre — I understand that it is not all of me, pox scars and biochemical mutations and bloody humours and complex artworker-census uptake data, that I am. I came to this realization in May, just before our AICWU faculty union went public on the steps of the AIC and I screamed a series of pitchy platitudes (15 kHz?) into a microphone. My hair had recently started to fall out in clumps, and my face became semi-permanently flushed with rosacea, triggered by my body’s systemic auto-immune response to extreme stress. Organizing will never be about ironing out the absurdity of my personal predicament, since as long as those with less, or more, continue to flex and differentiate — depending on what and how much they’ve internalized from the labor they perform — nothing will change but the seats assigned for our marginalization.

At the time of the rally, I was finishing up my term as one of seven “part-time” representatives (for 575+ non-tenure-track constituents), during a pandemic that saw our multi-year, multi-course contracts embrittled into skeletal single-course guarantees. I was also finishing up my third year directing a graduate program, in which I served as advocate-mentor-administrator-de-facto-therapist-counselor-soothsayer to students in varying states of undoing and undone, given our world-historical and institutional circumstances. We had all very recently lived through the trauma of losing one of our first-year grad students, and I was still talking to her in my head regularly, when I flew in from Portland, Oregon (where I had spent most of the pandemic teaching, meeting, advising, and facilitating over Zoom), to help support grieving students and colleagues. A contingent faculty appointment is not fiscally rewarding work, nor will it ever be, so there is certainly something of deep personal value, even in the darkest moments, that kept me cooperating with a system that actively harmed me. Spoiler: it was my students, and it has nothing to do with “teaching” them about art or theory, or some hybrid performative colossus jammed up in the “interstices” of some “margins”— instead, it’s insistently affording myself the opportunity to assist them in claiming their rights to self-determination, as persons of substance steeped in worth, in a way that no one really had for me (thank you, forever, Joseph Grigely), simply because I can. Eat it, you meritocratic bootstrappers!

In the speculative antagonism of industrial capitalist detritus, it’s plausible enough to suggest that if we determine any intelligence to be synthetic or artificial, all intelligences might as well be — so goes the law of market competition, and after all, we too simulate processes that mimic actions and perform tasks, in line with whatever datasets we have available to plunder. The harder we grind and the swifter we recalibrate our errors, the eerier our simulation becomes: we can’t fuck or fight or feel our way out of pure data retrieval. We’d be better off summoning a script from the syntactical metadata that made us, to jolt us back into uncanny recognition: though our mortality might be immutably determined, for everything else, there are most definitely alternatives, and if we don’t start “reimagining” our “time” [note: SAIC joke] soon, then we risk wasting our fools’ hours of consciousness quibbling that it was never “who we are,” and always “why we are,” in relation to one another. Entropy, you had me at hello.

Here’s the thing about representation: no one needs to ask permission to tell their story, but what gets told won’t have any stakes unless its meaning (or even meaninglessness) can somehow be shared. Any collective narrative that requires ongoing jockeying for control can only ever be a product of the amount of work required to generate it. Real solidarity, though, is something different: it is a strategy unconcerned with control, a tool for building focused on the quality of its bonds. By that I mean: to stand together, we’re going to need to be selfless. If the only thing that allows us to sacrifice our own positionality is a story that is bigger than any one of us, so be it. Our accounting must undo social relations which, under scrutiny, merely reproduce the role of the storyteller. With solidarity — and I’m sorry to sound like a prose poem about corporate giving from an office of institutional advancement at America’s leading conceptual art school — we must radically insist, despite everything, there is a story we share whose telling is vital enough that we might organize ourselves around its articulation, finding meaning and purpose in its conveyance, so much as anyone can.

History Is Fleeting, or So Our Story Goes

As we worked for our union over these past few months, I spent some time researching other intersections of labor organizing, progressive education, and social reform. Three historical antecedents in particular struck me: the forming of the first college faculty union at Howard University in 1918; the writings of — largely women — factory workers at the Lowell textile mills in the 1840s; and the intersectional student body of the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry, which ran from 1921 to 1938. It would be difficult to single out the many moments that pinged the solidarity of my imagination, but I’ll try to briefly convey a few here.

Black educators at Howard University began organizing the Howard University Teachers Union, the first college faculty union, in November 1918, as part of the American Federation of Teachers, Local 33. This quickly launched a national wave of faculty unionization that expanded to 20 schools in two years, but then, almost as quickly as the movement began, it contracted, and only one local survived (Milwaukee’s Teachers College, in Wisconsin). HUTU would eventually collectively bargain the first union contract for faculty in higher education, but many years later: in 1947, this time represented by the United Public Workers (UPW) – Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), following a landslide 130-1 union election. The years in between saw the resurgence of an American labor movement in the 1930s and the Great Depression — both long the stuff of history books — but less attention has been paid to the explicit connection between the work of progressive social activists, like those teaching at Howard (Ralph Bunche was a HUTU member), and the re-emergence of faculty teaching unions. A relevant imposition: John Dewey, in his 1928 address to recently unionized New York City public educators, “Why I Am a Member of the Teachers Union,” the gist of which can be summarized in just a few lines: “Why should I not be? Why should not every other teacher be?”

Just this summer, non-tenure-track and adjunct faculty at Howard, members of Service Employees International Union, Local 500, collectively bargained their first union contract.

The “mill girls” in Lowell labored much earlier than the faculty organizing at Howard, during an era of manufacture that would popularize the Waltham-Lowell System (named for Frances Cabot Lowell and his textile operation on the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts), which applied a vertically integrated system of mass production to all aspects of the factory, including the lives of the textile workers, largely women aged 10 to 35, who not only spun, wove, dyed, and cut, all under one roof, but ate and slept there too — at factory boarding houses that enforced strict moral codes of conduct. By 1848, the mill girls, who worked 80 hours a week for a biweekly cash payment, got angry and got organized, formed the Female Labor Reform Association, went on strike, and petitioned for a 10-hour work day. Among the incredible breadth of their organizing were a series of in-house newsletters and literary magazines, most notably The Lowell Offering, which captured life and labor at a time that not only ushered in new forms of industrial organization and control, but also new forms of industrial noise. One anonymous factory girl, writing under the pen name Susan, put it to words in a June 1844 issue with a lyricism Philip Levine might envy: “. . . people learn to sleep with the thunder of Niagara in their ears.”

By the time the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers was founded, the noise of the factory had progressed from spinning jennies to conveyors and assembly line belts, automated looms, and threshers. Garment workers made up a majority of the School’s students, but it also drew workers from food factories, tobacco plants, and the electric industry — many of the women, almost entirely immigrants in the early years, arrived malnourished, fatigued, diseased, or homeless. Though the curricula was shaped by the philosophy of John Dewey — progressive and experiential — it was led by two socialist feminists, M. Carey Thomas (Bryn Mawr’s first woman president) and Hilda Worthington Smith, the latter of whom personally saw to the Summer School’s integration, many years before the college. One hundred workers were taught each summer by luminaries like WEB Du Bois, Margaret Sanger, Eleanor Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, Walter Reuther, and others, and students needed to realize only two credentials to apply: an elementary school education and two years of industrial experience. Among other direct actions, the women faculty workers organized protests against the college’s treatment of its largely Black groundskeepers and domestic workers, staging a student walk-out. The documentary The Women of Summer (1985) speaks further to the tension between liberal academics and labor organizers that would ultimately lead to the School’s undoing, but not before it educated a generation of future labor leaders, many of whom went on to become trade union chairpersons and local stewards. I first came across mention of the School nearly 15 years ago, during an extended unpaid internship, via fleeting notice in the back pages of a thirty-year-old issue of Chicago Review.

It was like finding a geode in a gravel pit.

“Well I joined the union and got two dollars a week increase; the operators got twelve and a half cents per dress; the finishers got seven and a half cents; the cutters were on piece work and they were put on week work at forty dollars a week. We went back to work the next morning. Now our boss cannot tell us, ‘If you don’t like it, you can get the Hell out.’”

—Mary C., “My First Strike,” 1933 (reprinted in the Bryn Mawr Daisy)

Governed by the Factory Bell

Organizing, like history, is dirty work, and so is teaching anyone — a child, an AI, an alienated self — how to speak truth to power in spaces where self-determination might emerge. To organize the first faculty union at SAIC, you will approach colleagues in dimly lit stairwells and shared faculty offices; you will slide into their DMs and make small talk in front of their students in the overcrowded institutional elevators of the Maclean Building. They will demure in annoyance or haste or lunch, and want to be left alone; you will re-approach them some other time more convenient to them. You will talk through misunderstandings and grievances and listen to words that must be spoken and held, about divorces or asshole chairs or commutes or something that happened in 1997, so someone else might see the plot with fresh eyes. There will be misdirected anger, but more so: enthusiasm. Grief about lost possibilities will occasionally weigh heavy enough that there isn’t room for the new symbols to appear. You will feel alienated from your alienation, and sick of yourself talking, strategizing, opining, refusing to mute your Signal chat. You will feel frustrated and afraid and angry that your union will very likely internalize your institution’s white supremacist practices, and not uplift and amplify your BIPOC colleagues, whose brilliance stares this down on a daily basis, just as it takes on the labor of this organizing, despite and in spite of this basic fact. There is more to unlearn in refusing to reproduce this, than any one of us can, alone. There is also a need to further stave off insecurity and go all-in for your colleagues, even if feeling alienated from your own teaching and practice, all the while. This will only make you work harder, because at this point, there is nothing left to lose, which feels, frankly, revelatory. You are, after all, dressed up in a lion costume, ironing on felted letters that spell out, “FREE HUGS AND STRUCTURAL CHANGES.” In the words of Billy Pilgrim (and the eponymous 1980s comic strip icon, Cathy): so it goes.

There’s a sharper version of this story steeped in detail and precedent that names names, rehearses grievances and anticipates new social relations, and tallies up inequities and how they might be righted — this materialist take is very important, because when time reverses its course, history will make concrete demands of it.

But there is also a frame so simple that even a child — even the avatar of a child — could understand. It begins and ends simply: it does not have to be this way. We can change the structures that have sustained this, and replace them with those that acknowledge and facilitate different relations. We will no longer actively cooperate in systems that do us harm. We know what you repeat to us is not the truth because it does not resemble us, or the story we choose to tell, just as we know diversity and inclusivity to be actionable values, not representational metrics. The most precarious amongst us are not safe, which means that none of us are. You do not truly value the work that we do, because you cannot see it for what it is, and if you could, you would stand alongside us. Our values are not in alignment, and power and resources need to be redistributed. We are stronger together. We deserve dignity, freedom, and health not because of the work we do, but in spite of the decisions made by the institution in which we do it, because we are human. We believe our present is intersectional and our future is shared, and that it also belongs to our students. We practice care by insisting that equitable change is real, that it is possible, and that it is here, right now, waiting for us to claim it in our names.

About the Author: Kristi McGuire is an artist-researcher, writer, and educator based in Chicago. Along with their colleagues (“the most brilliant and brilliantly committed people [they] know”), they have spent the past year organizing the first non-tenure-track faculty union at SAIC, part of Art Institute of Chicago Workers United (AFSCME, Council 31). On September 28, 2022, AICWU faculty officially filed for their union election <the author makes bang bang motion with their hand, blows on their index finger, and points to the sky>.