Content Warning: This essay includes references to genocide and sexual assault.

I understood that we were going to sleep together as I twisted the spoon in my mouth. I scraped the chocolate mousse from the concave surface of the utensil with my tongue and allowed the chilled sugar to dissolve before swallowing. He stopped speaking mid sentence while telling me a story about his niece, and I raised my hand to demurely cover my mouth, suddenly self-conscious of the shape my lips might be making as they closed around the spoon’s handle. He must’ve noticed my embarrassment because he apologized quickly, paused, and added with a smirk, “I was distracted by the way you ate that. It was, uh, nice to watch.”

I laughed and pushed the chocolate mousse across the table, imagining as he took a bite how my freshly lotioned skin would taste and feel against his tongue. He swallowed. Tealight candles flickered on the table between us. The shrinking wicks cast off enough to faintly illuminate the lower half of his face, making his firmly ridged lips more noticeable. His cheeks flushed, smoldering like peach-colored embers, and I was tempted to touch them, overcome by the same urge that possesses me when I hold my hand above a frying pan I’ve just finished using to see if it’s still radiating enough heat to scald me. As his expression softened, his eyes narrowed in pleasure.

This gesture—slowly twisting the spoon and sliding it from between my closed lips, absentmindedly tracing the sloped metal with the tip of tongue—I realized, mirrored the greedy expression I would make later while sucking his cock.

I am reminded of Tita de la Garza, the ill-fated protagonist of Laura Esquivel’s “Like Water for Chocolate” whose erotic feelings for her lover Pedro are inexplicably infused into a quail and rose petal sauce dish after her mother forbids her from marrying Pedro. The dish inflames her sister Gertrudis with lust: she perspires pink, rose-scented sweat and is carried away by the revolutionary captain Juan Alejandrez, who makes love to her on horseback, overcome by her intoxicating floral scent. The mousse similarly became a vehicle for my desire, capable of transferring the intensity of my carnal attraction to this stranger. As he closed his lips around the handle of the spoon, he would understand how badly I ached to grasp his neatly braided pigtails like reigns while he pressed his mouth to my neck, and he would comply. Eating and lovemaking would become synonymous acts.

When I told one of my friends I was planning to cook dinner for our first date, they warned me against it. What if you botch the recipe? I explained that I would only make a dish I had successfully cooked before and that I would be cooking before his arrival, evading a scenario where I might be distracted or made anxious by our conversation, accidentally charring the spongy flesh of these neatly notched gnocchi or turning the tomatoes into an unsalvageable, slimy mush. I learned this lesson the hard way: I once offered to cook breakfast for an occasional lover after sleeping over and made several missteps after they playfully chastised me for not taking more initiative, over-salting the eggs and undercooking the pancakes, leaving a moist interior of batter.

I finished our dinner with this store-bought chocolate dessert because this is the way I end all dinner dates. Store-bought is the perfect hedge against coming across as senselessly romantic, asking for love too brazenly. It’s nothing! Just a little something I threw in my basket as I was leaving the grocery store. My favorite chocolate desserts to share with a date are a single slice of devil’s food cake, chocolate ice cream topped with a pinch of flaky lemon salt, or, on this occasion, single-serve jars of silky chocolate mousse.

Serving chocolate as the final note of our romantic dinner was both a self-indulgence (the perfect palliative for an unsatisfying date) and a shameless attempt to bewitch the unsuspecting. When he refused to finish the mousse, despite my insistence and his own courteousness, I pretended to be anguished: If you don’t, I’ll be so heartbroken. I’ll think you hated my company… He acquiesced and allowed me to pass him the spoon. He watched me watch his lips pucker as he swallowed the last mouthful of the custard-like dessert. I wondered, could he taste my thoughts in the mousse’s sugary richness? Drag me to my bed where we can spend the rest of the night making empty promises: just one more bite, I swear! And we would eat until we were lovesick.

Chocolate is one of the most popular tokens of affection exchanged between, and marketed to, lovers and the lovesick. A dedicated display of heart-shaped chocolates in festive containers materializes overnight in every supermarket and pharmacy in early February each year. A cluster of clickbait articles surface online: “10 Aphrodisiac Foods for Valentine’s Day”, “Is Chocolate a Catalyst for Romance?”, or “The Foods that are Believed to Boost Libido”.

Offering your beloved chocolates for Valentine’s Day was an obvious evolution of a Victorian tradition where lovers expressed affection through handmade cards adorned with puzzles, lines of poetry, or illustrations of flowers, love knots and plump, bow-and-arrow-wielding cupids; nineteenth century chocolate-maker Richard Cadbury, capitalizing on the Victorian’s fondness for theatrical displays of sentimentality and the growing popularity of Valentine’s Day, introduced heart-shaped boxes of chocolate in 1861 and marketed them as the perfect gift for lovers. The ornate boxes contained bonbons filled with marzipan, chocolate-flavored ganache and fruity crèmes. After the chocolates had been eaten, the boxes were often used to store love letters, lockets of hair, buttons, and other treasured mementos.

Less obvious is how chocolate earned its alleged reputation as an aphrodisiac. Despite chocolate’s high concentration of tryptophan—a building block of serotonin, a key chemical for sexual arousal—and phenylethylamine—a relative of the feel-good chemical amphetamine which your brain naturally produces when you fall in love, scientists and sexologists cast doubt on chocolate’s and other so-called “love foods’” libido-boosting properties. Any palpable effects on one’s mood from consuming these foods, they point out, is nullified by digestion. If chocolate has any aphrodisiac properties, they are psychological, not physiological.

I preferred to safeguard chocolate’s mythic reputation as an erotic stimulant the way I would defend a beloved family recipe whose origin is questioned: Maybe grandma lifted her famous chocolate chip cookie recipe from the reverse side of some Nestlé Toll House packaging. Valuable because of its exclusivity as a safeguarded family secret, the recipe, my inheritance, would become worthless. I would have to admit my pleasure, my love for chocolate, is rooted in unapologetic theft. An act of thievery I had no hand in committing but that I enjoy the spoils of nonetheless. An act that entangles me in the relationship of perpetrator and victim, wittingly or unwittingly.

Eating and lovemaking are a similar, fraught entanglement because they are an exchange made possible by other people, some we may know intimately and some we may never know. After all, consumption and consummation share a common prefix, “con–”, which means “with” or “together.” They establish a relationship between previously discrete subjects: “to make a union complete by sexual intercourse/to make perfect, complete” or “to use up, eat, waste.” The lover expresses desire physically while the consumer devours the object of their desire, destroying it. Both actions imply pleasure. However, neither guarantees equal footing in the relationship between the consummating lovers, or between the consumer and the consumed.

I wonder, how many lives has this dessert lived—as a recipe scribbled on scraps of paper or dictated from one cook to another—before some underpaid supermarket employee whipped egg yolks into melted chocolate and placed the finished, chilled product on the refrigerator shelf I plucked it from. Who is my lover? What chain of events brought him to my table where he chews the doughy gnocchi and tomato dish I baked, hoping to find a taste that would bring him pleasure? Is his assertive personality—the unrelenting eye contact and insistence he’ll spoil me in return—the consequence of being the eldest of five children; as he speculated after two glasses of wine, a penchant for hospitality he inherited from his Puerto Rican family; or simply a learned trait, an approach he’s cultivated through frequent dates with quiet, nervous transsexuals who fear spooking off the one man who will actually go on a date with them. Who would devour who? Would he be mine, or would I be his? A combination, more likely.

How did I inherit this romantic image of chocolate? The short answer: theft.

Chocolate, like other foods believed to be aphrodisiacs (think: chili peppers, vanilla, oysters) were all once considered luxuries to European aristocracy. And luxury creates hierarchy—the principal language of capitalism, spoken through ownership and consumption, transforming us into objects that in turn possess other objects.

The squat-faced Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés landed on the Yucatán Peninsula in 1519 with a single goal: to colonize Mesoamerica’s interior in the search for gold and other luxuries that could be shipped back to Spain. In November of the same year, Cortés led 500 conquistadors down a causeway to Tenochtitlán, the Aztecs’ elegant island capital. The Aztec Emperor Motecuhzoma II greeted the Spaniards with bouquets and wreaths of sunflowers, magnolias, and cacao blooms and himself fastened a necklace made of golden crabs around Cortés neck. The Spaniards were invited to a lavish banquet, which Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of the Spanish swordsmen, described decades later in his memoirs.

During the meal, servants brought Motecuhzoma cup-shaped vessels of pure gold throughout the meal that contained a foamy beverage made of roasted and ground cacao seeds mixed with water, flavored with various spices and herbs, and thickened with cornmeal. The Aztecs explained to Cortés that Motecuhzoma took the drink when he was going to visit his wives, suggesting it was the source of his uninhibited libido (another Spanish chronicler exaggerated that the emperor fathered more than 100 children, implying the ruler was sex-crazed to produce such a dizzying number of offspring.) The more than fifty jugs of earthen-colored, frothed cacao, was served with great reverence: cacao pods symbolized the human heart torn out and presented to the gods during Aztec slave sacrifices because they were similarly shaped repositories of precious liquids—chocolate and blood.

(I understand: sitting across from my lover, I present the chocolate mousse with a single spoon as if saying, here is my heart. Torn out, dripping blood. It’s yours—if you want it, of course. But this image, this metaphor, itself is stolen. The few existing sources on Indigenous life in Pre-Columbian Mexico, such as the Florentine Codex, were assembled and preserved by Spanish colonizers or Mestizos, the stories became muddied, exaggerated, or used as fodder to justify what came next.)

Christopher Columbus, famously known for his self-congratulatory, harebrained pronouncements, came upon cacao in a Mayan canoe he took hostage, but mistook it for almonds, baffled when he noticed the natives stooped to rescue any beans that fell to the ground “as if an eye had fallen from their heads.” The Spaniards found the bitter, gummy drink unappealing but recognized the economic importance of cacao. Both the Mayans and Aztecs used cacao beans as currency.

The Spanish fought for control of and taxed both the production and trade of cacao beans. The merciless colonizers identified and extracted luxuries in the Americas—such as silver, gold, and chocolate—that would be shipped back to Europe, and sold. They set up plantations in the oven-hot plains of Soconusco in Southwest Mexico, along the border of modern-day Guatemala. Creole Spaniards living in this “New Spain” became the first to develop a taste for the frothy chocolate beverage. They perverted the traditional Mesoamerican recipe by heating the beverage and adding sugar to sweeten its bitter taste. Chocolate was gradually adopted by the nobility in Spain as military men, civilians, and Jesuit priests passed back and forth across the Atlantic, bringing this new commodity with them. Considered the perfect all-in-one food, it earned a reputation among Europeans for its energizing qualities (chocolate was the first caffeine fix available to Europeans, arriving earlier than both coffee and tea.)

The Spanish enslaved Indigenous Americans who knew how to cultivate and harvest the crop until Pope Paul III Farnese published the Sublimis Deus in 1537, decreeing that any Christian who enslaved an Indigenous person would be excommunicated; however, the decree made no mention of the encomienda system (slavery with some minor semantic differences; Indigenous people were still enslaved) nor African populations. This guaranteed the emergence of capitalism and the accompanying, rapid explosion of human trafficking through the Atlantic slave trade, beginning one of the worst holocausts in human history. In the late 17th century the sugar plantations of Brazil and the Caribbean expanded rapidly through the labor of hundreds of thousands enslaved Africans, driving down the price of sugar on the European market by 70 percent and making chocolate more affordable to the masses.

Chocolate’s rapid transformation into a global commodity that could satiate Europeans’ sweet tooth was possible because of the mass suffering and death European colonists inflicted on Indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans. By the end of the 17th century, only 10 percent of the original Indigenous populations of the Americas had survived Spanish conquest and the introduction of Afro-Eurasian diseases such as smallpox, measles, and cholera. More than 13 million Africans were kidnapped and trafficked across the Atlantic during the barbaric Middle Passage while another two million died during the harrowing journey. As Sadiya Hartman writes: “Death wasn’t a goal of [enslavement] but just a by-product of commerce, which has the lasting effect of making negligible all the millions of lives lost. Incidental death occurs when life has no normative value, when no humans are involved, when the population is, in effect, seen as already dead.” They became possessions, consumable and disposable.

As Europeans ransacked the Americas and Africa to satisfy their appetites, chocolate became more popular and retained this notorious reputation as an aid for lovemaking. It was christened the “elixir of love” by the Venetian-born adventurer, author, and womanizer Giacomo Casanova (whose name is now synonymous with “fuckboy”).

Another European whose name would become an eponym for a sexual temperament, the Marquis de Sade, was a self-professed chocolate lover “capable of wolfing down frightening quantities.” Sade and his servant were arrested in 1772 by the King of Sardinia after rumors spread that he served his party guests chocolate pastilles laced with Spanish fly, an alleged sexual stimulant made from blister beetles that caused inflammation of the genitals. The party degenerated into “one of those licentious orgies for which the Romans were renowned” with the usual whippings and bouts of sodomy; Sade himself buried his nose between the buttocks of four women to smell their turnip-scented farts.

The truthfulness of this tale has been questioned. Scholars argue his guests weren’t served sexual stimulants, that the women were prostitutes and the pastilles were probably anise candies rather than chocolate confections. In all likelihood, he attempted to rape and later, with the hope of making them less resistant to his sexual advances, poisoned the four women—who reported him to the authorities when they became pale and vomited uncontrollably. But the story was repeated and embellished by Sade’s friends and enemies alike until it became myth-like. The poison pastilles, real or fake, suggest that the ecstasy, the momentary pleasure Sade might experience by fucking these women, pressing his nose into their erogenous zones, superseded everything, including the value of human life. He wanted to possess these women so fiercely that their lives became negligible, disposable. And chocolate became the vehicle to either bewitch or punish them.

With wholehearted belief in chocolate’s bewitching qualities, I sheepishly gazed into my lap, subconsciously picking at my overgrown cuticles, before my date suggested that we move to my bedroom to continue the evening. I agreed. We cuddled together under the pretense of watching the 1998 romantic comedy “The Wedding Singer” (his recommendation; although, we both had confessed during dinner that we had fond memories of watching romantic comedies with our mothers growing up). We sacrificed the other half of my bed to my petite laptop. I pretended to watch the opening scene. However, I was acutely aware his eyes wandered down the seam of our bodies pressed together. I shimmied, turning to face him, and grinned, delighted by the sight of his lips. He whispered a compliment I’ve since forgotten but that caused me to swoon, like a tulip collapsing open in the early morning sun. There were small crumbs of chocolate in the corners of his mouth that may have disgusted someone not blinded by lust, but I was enraptured. I sought the lingering taste of the cocoa as he kissed me.

Afterwards, my lazy, post-coital comfort quickly dissipated, replaced by a feeling that I had been duped, misled by his sweet nothings, repeated declarations that he wanted me to visit the restaurant he worked at so he could spoil me in return, promising Tuscan wines, artisan cheese, and Alpine-inspired cuisine. These pleasurable visions turned sour. I felt like my loneliness would never end. This fear eased the next day when he texted, admitting he had been smiling all day thinking about our date. We made plans for the following week, but he never responded when I texted the day of our tentative plans. Another chaser. I should’ve heeded my friend’s warning and stuck to a non-committal date over drinks at a bar.

Being ghosted is an inevitable, unremarkable part of dating, but my insincere lover’s rejection was compounded by an onslaught of men who had disappeared without explanation. I sent him a message the following week in a rare, optimistic mood that soured with each passing hour, like unrefrigerated yogurt that slowly spoils until it becomes inedible, as I surrendered to the fact that his disappearance was permanent. I was furious because I couldn’t understand why his desire was so short-lived while mine continued to linger. My appetite wasn’t satiated. I succumbed to this out-of-proportion rage and sleuthed to uncover his Instagram, where I discovered a cryptically captioned photo of him with his arm draped across someone else’s shoulder. His partner, I guessed. He mentioned his partner during dinner but corrected himself, saying ex-partner twice as if he was still adjusting to the newness of the term himself, and told me they had moved to California with their cat. Evidently, their separation was short lived. Or perhaps a lie.

Chocolate was also associated with another kind of desire in Baroque Spain—revenge. Europeans discovered the strong taste of chocolate made it an effective disguise for poisons. A French fairy tale author wrote a story about a Spanish “lady of quality” who felt betrayed by a lover who ghosted her without explanation. To punish her lover for his slight, she lured him into her house, where she offered him a choice: a dagger, or a poisoned cup of chocolate. He chose the poison. He fussed, telling her it needed more sugar but drank anyway. Within an hour, he died, collapsing in a pool of his vomit, which filled the room with a rotten egg smell. The Spanish lady watched without flinching or making a move to intervene. Her barbarity appealed to me.

But I could not poison my lover—obviously. The thought alone made me feel guilty. Am I just as Sade or these European colonizers, so single-minded in my desire to possess the object of my desire that I showed little regard for the human life behind my wanting? Did he not deserve the agency to reject me? I wonder, why does the way I love so closely resemble ownership? Even now, as I write, I suspect part of the motivation behind this essay is the attempt to possess this lover, eke every drop of pleasure out of our brief encounter, and present a beautified perspective of this night we shared, seeing him as a story, an opportunity, an unspoiled landscape ripe for my conquest.

I considered taking another Tinder date to his restaurant just because I wanted to see him, to smell his leathery, burnt tobacco scent again, and hear his voice as he described the dish I would order: gnocchi dumplings made with spinach and ricotta, served in a fresh pecorino cream. But he did not want to see me. If I showed up at his workplace, I would turn him into something less than a human being, as though he were as passive as anything else I wanted, any other object I wanted to consume—a bottle of wine, a book, or a single jar of chocolate mousse. Instead, I deleted his number, cried, and resolved that I would never serve a prospective lover chocolate again.

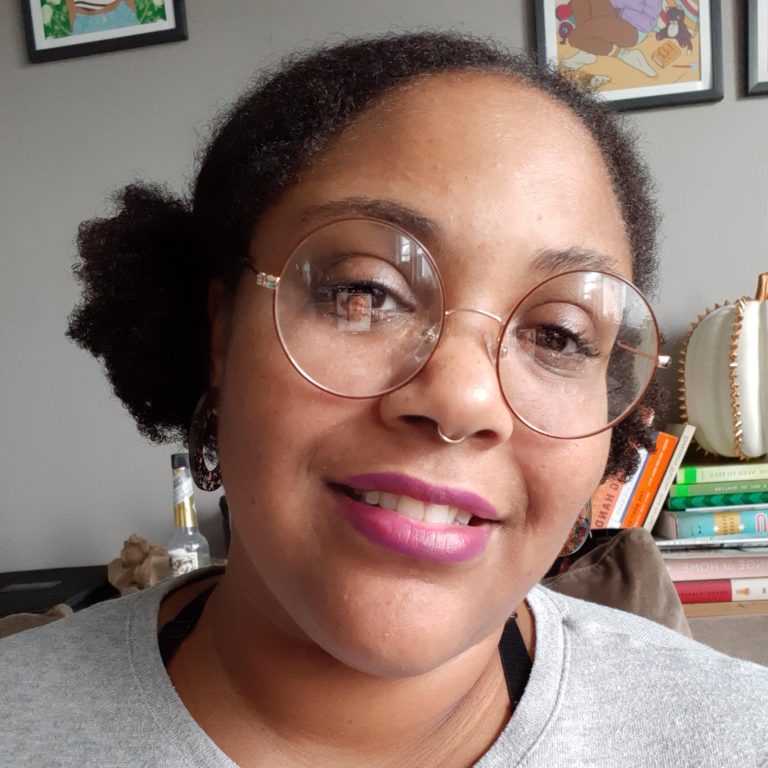

About the author: Riley Yaxley is most often a dinner party host, a fishkeeper, a beach rat, a flâneuse, a glutton, a flirt, a dancer, a delinquent daughter who forgets to call her mom; and she is also a writer and editor.

About the illustrator: Teshika Silver is a freelance illustrator, designer, teaching artist and spiritual cultural worker spending time and living freely in Washington Park, Chicago. Follow her work on Instagram @astratesh.