The term “South Asian” can be contentious for people born in and descended from the subcontinent: including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. While aiming to encapsulate the many disparate experiences within a region, it can lead to the forgery of identity that doesn’t really exist. Elements of culture, religion, gender, and even local various biomes within the geographic area lend to the mythology that erases intentional ways that describe how many people live. At the same time, “South Asian” like the term “Desi” eradicates narratives of nationalist supremacy. “South Asian” and “Desi” create a delicate thread of shared experiences for those from the subcontinent, despite the differences in language, religion, food, and dress. This thread weaves a collective story that transcends oceans and post-modern borders.

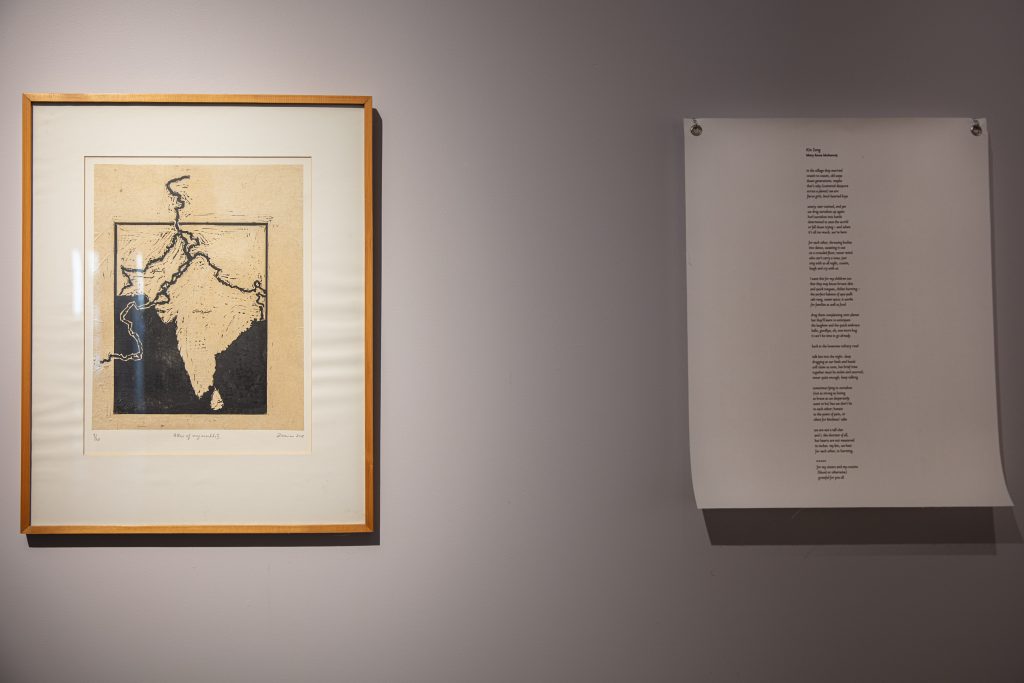

Testimonies on Paper, curated by Andrea Moratinos and advised by Dipika Mukherjee, portrays the push-and-pull of these terms at the South Asia Institute (SAI). South Asian women of different nationalities, religions, ages, and ideologies are brought together in a shared space. They agree, contradict, and provide multiple perspectives on South Asian womanhood. Selected poets responded to and selected artworks from the South Asia Institute’s Hundal Collection that spoke to them. Through the pairing of art with poetry, the show integrates the idea of singular experiences in lived experience and beliefs in mythology informing womanhood. Moratinos invited poets to respond to the visual art in the show.

For example, House With Four Walls, opening the show by the Indian-American artist Zarina, contains seven black-and-white etchings with corresponding subtitles. Each component carves out space for meditation on displacement and childhood memory. The prints, strong and contrasting, depict the heat of sun-bleached earthen walkways evoking the subtitle: “I Run Outside to Play and Burn my Feet.” Reed mats used as beds in the summertime appear along with the descriptor: “On Long Afternoons Everyone Slept” and pieces of ubiquitous domestic architecture. The plain detail signifies the baggage muddles these recollections—they challenge the idea of memory being only nostalgic, whimsical daydreams. The imagery evokes a need to grasp these signifiers of memory and culture before they slip away, inevitably taking a piece of selfhood with them.

Paired with House With Four Walls is a poem by Sri Lankan-American poet Mary Anne Mohanraj, titled “Kith and Kin.” Through a story about trying to replicate a dish by her grandmother, the poem expands upon Zarina’s childhood. Mohanraj’s need to replicate and share cherished secrets—like a spice mix—centers the urgency of experiencing, preserving, and knowledge-sharing from memory which activates the theme of generational labor. She praises her ancestors for holding onto these recipes and passing them down. Mohanraj ruminates on the desire to capture generations of South Asian recipes central to inherited identities, eclipsing physical coordinates.

In doing so, she aims to spread her culinary practice beyond maternal tradition. Diasporic reality is more than retaining and safeguarding sentimental rituals that transcend time and space, but is a space of re-imagination, too. The notion that South Asian women are historically bound to religious and state-enforced behaviors, dress, and expectations is pervasive. However, when faced with codes of conduct, Desi women forge new identities, exercise agency, and use the inter-generational experience to reckon with old and new challenges—as seen in Ami Kaye’s Gaiavision, paired with Shahzia Sikander’s Maligned Monsters II.

Near the end of the show, much like the transition from childhood to womanhood, defiance replaces the feeling of longing. The featured poets and visual artists tug at the idea of boundaries that generations before enforced. Berlin-based Pakistani artist Bani Abidi’s Flailing Barriers references the various demarcations that pepper Pakistan’s geography. The brightly-colored gates take many forms but are all isolating reminders of state-sanctioned control, economic division, and identity policing in a politically-torn nation. Dipika Mukherjee’s poem Generations accompanies this work and recounts the battles fought by women—from goddesses to grandmothers in the divine and mortal realms. When juxtaposing Flailing Barriers, the poem’s subjects are faced with battles waged against their womanhood within their respective domains. Abidi’s observation of a religious nationalist republic remains poignant if it stood on its own, just as Mukherjee’s supplication to the Hindu goddess Durga.

Overall, the show doesn’t aim for audiences to digest a clear narrative from these vignettes nor define Desi womanhood. However, visitors take away that no nation can claim authority over the massive geography that makes up the subcontinent. On a deeper level, Testimonies on Paper invites visitors to leave with more questions and embrace multiplicity. South Asian womanhood isn’t predicated by “South Asia,” rather the term “South Asia” opens doors to contemplate the meaning of “South Asian womanhood.”

Testimonies on Paper is on view at the South Asian Institute from January 20 – June 17, 2023. Participating artists include Zarina, Ayesha Sultana, Laila Rahman, Shahzia Sikander, Bani Abidi, Nasreen Mohamedi, Naiza Khan, Salima Hashmi, Meher Afroz, and Rana Begum. Participating poets include Mary Anne Mohanraj, Nina Sudhakar, Bhaswati Ghosh, Kashiana Singh, Dipika Mukherjee, Ami Kaye, and Shikha Malaviya.

About the Author: Saadia is an illustrator and writer based in Chicago, IL. Trained in South Asian history, her writing focuses on religious nationalism in art, the South Asian female form and gender roles, and the religious undertones of artistic movements at the cusp of the 19th-20th century.