Featured Image: Talk from the mangrove. A man sits in front of a background that is part-mangrove, part-bookshelf. He wears a red graphic t-shirt and holds his hands up above his eyes as if looking for something in the distance. Courtesy of Tiny Domingos

“I want our artists to focus on positive narratives about climate change,” artist Tiny Domingos told me during a Zoom interview in June 2021. “I don’t know if we will write stories together or make animal masks; we will do whatever we need to.”

Domingos, an artist and educator based in Berlin, was Compound Yellow’s Astral resident for the summer of 2021. Compound Yellow, an art space in Oak Park run and founded by Laura Shaeffer, dedicates its space and resources to experimental art, music, and creative thinking. One of its programs, the Astral Residency, is focused on working with artists living outside of the art space’s physical community. The workshop title for Domingos’s residency was “Hybrid Togetherness,” a term that referenced, among other topics, a better understanding and pursuit of human connectivity with the rest of nature. In an effort to bring together artists and community members to discuss plans for environmental changes, Domingos focused the workshop around creating positive narratives and raising awareness of our integration with all life on the planet in a way that encouraged creativity and artistic narratives.

It is strange and equally significant that a workshop so involved with discussing the intricacies of the physical world would take place remotely, as artists and other individuals connected with the Compound Yellow community participated from their homes in Chicago, Wisconsin, Berlin, Shanghai, and other places spread out across the planet. While connecting solely over Zoom had its limitations, Domingos’s workshop and the concept of virtual residencies like Compound Yellow’s hold intricate potential for the formation of community, sharing of artistic work, and each participants’ understanding of their own relationship with the physical world.

“Hybrid Togetherness’s” three sessions, each held on Zoom, contained equal parts of learning new ways of seeing the environment and working artistically to explore human connectivity with nature. Domingos led discussions of scientific theories of symbiogenesis and interconnectivity, including the work of Chicago-born scientist Lynn Margulis and her collaboration with James Lovelock on the Gaia principle, which proposes that the entire Earth itself has characteristics of a cohesive living organism.

Much of the workshop’s material intended to uncover or shed light on aspects of nature that were more intricately connected than what one might think, which show how different forms of life work together for survival. One such phenomenon discussed was the mycorrhizal network by which individual trees can send water, nutrients, and other minerals to protect each other. These networks, called mycelium, are formed by tiny, delicate threads of a fungal organism that wraps around tree roots and spreads for miles underground. Participants discussed the axolotl, a salamander native to Mexico which can live in both water and on land and has the ability to regenerate limbs. As a participant, I sat alone at my desk after a session and watched an artwork Domingos referenced, Diego Ramirez’s video piece “aXolotl’s Happiness,” in which a part-man, part-axolotl walks alone around his small house carrying out mundane tasks. Perhaps ahead of its time, the piece constrained the axolotl hybrid to his home and to his yard; alone and self-isolated.

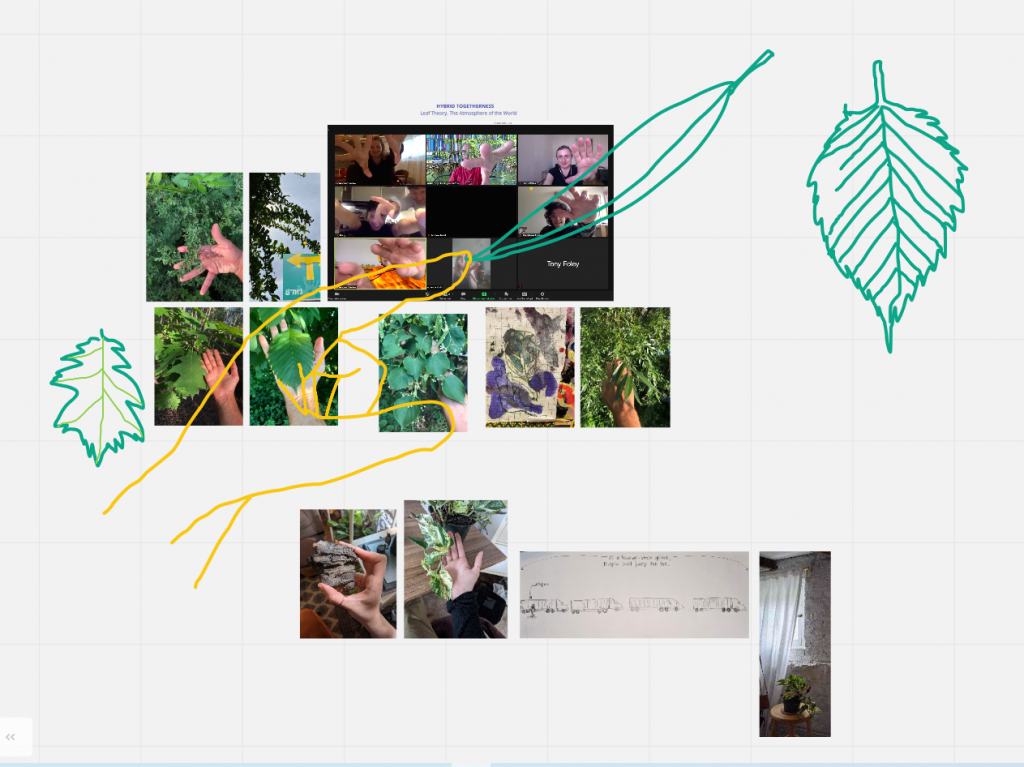

These sources and readings acted less as lectures and more as generative prompts for the artists. Domingos asked participants to engage in exercises that felt grounding and whimsical at the same time: to close our eyes and mime swimming through the air or to sit and have a conversation aloud with a plant. Participants documented their hands next to leaves, noting their similar size and shape. The exercises were simple and lighthearted, but this left room for deeper original thought that can be difficult to find. For Shaeffer, this informality was one of the most life-giving aspects of the experience. “The playfulness of the workshop; the plasticity that we all felt because of how the imagery was brought in; it allowed me to move out of the workshop and feel that I could interact with trees and nature around me in a different way. It gave me permission to go further.”

These prompts also led to multiple artistic experiments and collaborations between participants. In a video piece “A poem for a tree,” artist Amanda Loch reads an original poem to an old, tall pine tree, pausing occasionally to look up and make “eye contact” with its bark. When one workshop session ran over time, a few stayed to play with virtual backgrounds of trees or plants on their Zoom windows, changing the lighting of their space to let the virtual images of the physical world leak over onto their bodies.

It’s both fitting and disjointed for this workshop, so focused on the physical world, to take place over Zoom. On the one hand, it utilized the tools at hand that are already inextricable from our daily lives and opened up a portal for connections between artists and activists in different states and countries that would never have been made had the participants been required to meet in person. In the spirit of the Astral residency, we were able to meet in the present moment but also at vastly different points of space and time: as I and other Chicago-area participants stifled yawns and hold cups of cooling morning coffee, artists on the other side of the world sat in an evening glow or in the long shadows of apartments at night.

On the other hand, the video-conferencing medium’s limitations were consistently present. Voices and faces glitched in and out over slow internet connections. Artists tried to share their work but struggled to navigate Zoom’s round-about way of enabling video sound or accessing control. The organic synchronization of community that comes so effortlessly to groups in a shared space was difficult to emulate when each participant, alone in their own space, leaned forward and forgot to unmute themselves or, in the case of internet issues, found that the insight or story that came to them in their own space, which they felt pressed to share, couldn’t be understood by the group at all.

I heard a similar sentiment from Compound Yellow’s previous Astral residents Benjamin Shepard and Job Zheng (also workshop participants), who in spring of 2021 under the institutional performance Pityless Consulting made a series of Creative Microdoses from where they were working in Shanghai; short creative prompts for members of the Compound Yellow community in Oak Park. “There’s a competitive advantage that comes to having a physical body,” Shepard said, as we discussed what it felt like to make work for a place that the artist doesn’t physically inhabit. “It’s hard [as an Astral resident], not to have one.”

But for all of the disembodiment and clumsiness of the tool, the virtual format makes unique connections and possibilities accessible to participants and artists alike. “The way that we all embraced the imperfection of the medium and the glitches and problems in a fun and playful way,” said Shaeffer, “made it so much more of a generative series [for my practice.] It was alive; it was breathing.” Artist and educator Tony Foley felt that the virtual format allowed him to engage with a creative community that wasn’t as accessible to him in person, and had the unique opportunity to listen to one of the workshops from the edge of a lake in Wisconsin. The capabilities of the Zoom format were able to bring him full circle: uncovering the environment’s connections and possibilities while existing in its physicality at the same time.

The Astral residency provides something invaluable to an alternative arts space like Compound Yellow, both to its body of work and to the artistic and local community that surrounds it. Something about disembodiment is useful in the fragile connections drawn between workshop participants across the globe or forged as an email containing the results from a creative prompt is sent back from Chicagoland across time and space to an inbox in Shanghai. Even if a workshop session seems isolated and distant, regulated to one small screen and a few hours of our broader existence and day-to-day living, it still makes itself known; it still shows up later.

Throughout these sessions, I felt the tight-knit connection between the urgency of changing the world to sustain a better environment for the planet and the time we spent together on Zoom learning about the marvelous systems of nature that became a kind of life-giving fabric between species and types of plants. The art and shared discussions gave clarity to our inherent human dependence and connectivity with nature, like the interconnected relationship between tree roots and the delicate mass of mycelium deep in the earth.

Aboveground and often alone in our bedrooms or studios, the “Hybrid Togetherness” participants also formed a tentative network, communicating with each other across the void of oceans and time zones. Zoom was our bridge. We shared our work and tried to help each other across language barriers and bad internet connections to share videos and enable sounds. When the conversations went over the predicted time of the meeting, some had to leave without interrupting to say goodbye: they waved, fuzzy, at the camera before cutting the connection. Our presence, along with our collective passion for a positive, cohesive future for our environment, was held together delicately; a fragile, temporary, and vitally important network.

Josepha Natzke is an artist and writer living in Oak Park, IL. Her writing strives to draw connections between artistic communities and practices that share similarities despite differences in location and cultural context, as well as to share others’ creative work with the broader audience of artists and non-artists alike.