This article is part of a partnership between Sixty Inches from Center and Black Lunch Table (BLT) partnership, Crowdsourcing the Canon—an editorial series diving into the lives and practices of Black artists based in the Midwest, especially those whose Wikipedia pages lack sufficient citations.

In the heart of Iowa, where the rolling plains meet the sky, resides an artist who seeks to explore all there is regarding the intersections of identity, race, and the African American experience. T.J. Dedeaux-Norris is an under-recognized and compelling figure in contemporary art, who has received startlingly little public attention in contemporary arts discourse despite working consistently since the late 2000s, and showing work in prestigious institutions such as The Studio Museum in Harlem. Their multifaceted practice spans painting, performance, and video art. They have completed various residencies in places such as The MacDowell Colony (2016) and The Fountainhead Residency (2013), won numerous accolades for facets of their practice, and has worked as a tenured track professor at University of Iowa School since 20161.

Dedeaux-Norris, also known as Meka Jean, was born in Agana, Guam, in 1979. They moved to Gulfport, Mississippi, with their family when they was just three years old. This early relocation was a significant part of their upbringing, as they grew up in Gulfport before eventually moving to Los Angeles in 1995 to live with their biological father and pursue a rap career. Dedeaux-Norris’ journey into the world of art consequently began with a unique blend of influences.

Dedeaux-Norris’ journey to becoming a fine artist was influenced by their diverse experiences and the environments they lived and grew up in. Reflecting on their time in New Orleans, Dedeaux-Norris shared how their interactions with the local community and the gentrifying neighborhoods were both research-rich and personally taxing. They stated, “Initially, as an artist, it was very interesting for research purposes, but personally and on a daily basis it became quite heavy to constantly have these interactions, which felt equivalent to being put in a time machine and taken back 100 years“2.

Dedeaux-Norris’ decision to become a fine artist was also shaped by their desire to resist and critique the changing artistic climate in historically Black neighborhoods. They noted, “Part of me felt the need to occupy this same space as a position of resistance or in opposition to the new gentrifying Wild Wild West of New Orleans”3. They received their undergraduate degree from the University of California, Los Angeles, and later graduated with an MFA from Yale University School of Art in 2012. Their time at UCLA was marked by a creative fusion of hip-hop aesthetics and academic life, a theme that would continue to permeate their work.

One of their early works is a video piece titled Licker, 2008. Released in 201, this video piece is a provocative exploration of identity, race, and the intersection of art and academia. In this 4:47-minute video, Dedeaux-Norris, scantily and outrageously clad, parades through the UCLA campus, rapping lines like, “I’m that Black Cindy Sherman and that little Kara Walker. Basquiat resurrected from the dead motherfucka….“. Their journey takes them from the inside of a university hallway locker to the façade of the Broad Art Center, and finally to an outdoor sculpture garden where they provocatively mounts and licks the breasts of Gaston Lachaise’s sculpture Standing Woman.

The piece brought out a bold statement on the visibility and representation of Black women in spaces traditionally dominated by white narratives. By transposing the language and aesthetic of hip-hop onto a backdrop of art historical objects and institutions, Dedeaux-Norris challenges the viewer to reconsider the boundaries of these worlds. While their actions in Licker provide shock value, they are also a deliberate critique of the exclusionary practices within the art world and a reclamation of space for Black female bodies. It was an early piece that explored personal identity and stereotypical representations of Blackness.

They have consistently created alter-egos in their work, one being Meka Jean. In conversation with Charlie Tatum, Dedeaux-Norris shared their thoughts on their alter-ego, Meka Jean: “Meka Jean is a combination of Tameka Jenean, so my first and middle name. My babysitter would be like, ‘Meka Jean, where are you?’ and my family calls me Meka, Meka Jean. She is basically that 3-year-old girl, that 4-year-old girl singing in the brush. Sort of no limits, not yet self-aware about gender, race, identity, just sort of open“4. This alter-ego allows Dedeaux-Norris to explore their identity in a playful and uninhibited manner.

Dedeaux-Norris’ assignment for The Art Assignment, titled Become Someone Else, (2015) invited participants to transform themselves into their own “Mythic Being”. This exercise is a reflection of their belief in the transformative power of art. Dedeaux-Norris believes that by becoming someone else, even if just for a moment, we can gain new perspectives and insights into our own identities.

Dedeaux-Norris’ work actively interrogates and redefines notions of Black identity. In their words, their “practice critiques the invisibility of Blackness in cultural forms built upon the appropriation of popular and sacred black expressions”5. This critique is shown in their series of sculptural paintings made from torn bed sheets, painted fabrics, and reconfigured representations of the United States flag. These pieces, part of their Almost Acquaintances‘ exhibition at the Ronchini Gallery in London in 2014, examine the decay and fragility of modern life, mediated through their remote experience of Hurricane Katrina by proxy of their family.

The socio-political contexts that inform Dedeaux-Norris’ work are deeply rooted in their personal experiences and the broader African American narrative. Growing up on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, they witnessed firsthand the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. This event became a central narrative in their practice, and became their way of amplifying the resilience and vulnerability of Black communities. Their work reminds us of the socio-political challenges faced by African Americans.

One of their (arguably) most striking pieces Untitled (Say Her Name), 2011-15 critiques the invisibility of Black women in cultural narratives. This work is a powerful commentary on the erasure of the identity of Black women and the need for visibility and representation. Curator Kanita Fletcher describes this piece as follows: “Norris sits expressionless in front of a plain white background. [Their] lips appear pursed, but gradually as [they] pass through a series of facial movements, we see they actually are glued together. For nearly five minutes, the viewer watches [them] painfully struggle to free [their] mouth. With this silent, minimal gesture, Norris speaks to the silence and invisibility surrounding the loss of Black women’s lives for which the campaign #SayHerName was created to address. The hashtag refers to the number of women and girls who are killed by law enforcement officers, and how racism and sexism play out on black women’s bodies.”6 Dedeaux-Norris uses their art to bring these issues to the forefront, creating a space for dialogue and reflection.

In 2021, Dedeaux-Norris staged their own estate sale as a traveling exhibition, The Estate Sale of Tameka Norris, first shown at the Des Moines Art Center. They explored the roles they’ve had throughout their life: rapper, video vixen, audio engineer, massage therapist, phone sex operator, stripper, prostitute, a sexually exploited, uneducated person, porn star, occasional drug dealer, barista, customer service call centre agent, professor, and art star—all parts of their past identities which now inform their art and social practice. In the exhibition, Dedeaux-Norris critiques systems of race, sex, gender, religion, education, healthcare, and class, as well as the complexities of family dynamics and histories. The title references New Orleans’s history of funerary celebrations and parades, as well as Dedeaux-Norris’ Mississippi Gulf Coast family, and the jazz funeral for victims of Hurricane Katrina.

Their contributions to broader conversations about representation and visibility in the art world cannot be overstated, they are noted for their institutional critique as well as their references to canonical works of art such as their recreation of Bruce Nauman’s Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square, 1967-68. Yet, there is a noticeable lack of comprehensive documentation of their work. This oversight highlights a broader issue within the art world, one that could be considered parallel to the concepts explored within their practice—the underrepresentation and marginalization of Black artists, and more specifically the underrepresentation of Black queer artists of the diaspora.

Their work is also all about communal exchange and connection. Dedeaux-Norris leads art therapy sessions which have been shown to reduce depression and anxiety, increase self-esteem, and help in socializing with others. Their work provides a window into the meaning and purpose of life, offering solace and understanding to those who engage with it. Their work is a testament to the strength and resilience of the human spirit, a reminder that even in the face of adversity, we can find beauty and meaning.

Look at Dedeaux-Norris’ artistic journey, and you get to see just how resilient and determined they are. They consistently blend personal experience both past and present into their work in various mediums, teaching, and residencies.

On that same note, after eight years as a professor at Iowa University, they plan to begin working towards a doctorate as the next phase of their artistic journey. Dedeaux-Norris will be focusing on embodied research and practice, as a way to heal their body from exhaustion, disease, generational trauma, and grief. Focused on centering their mind and body, this research includes acupuncture, massages, boxing, chiropractic alignments, and spiritual practices. They are now trying to further the reach of this research through understanding the tools marginalized folks use for resilience, their effects and their reasonings throughout generations with the knowledge gained through scientific research.

Their work has been featured in numerous important exhibitions, including “Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art” at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and “Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art” at the Yerba Buena Museum in San Francisco. Each exhibition is hopefully a step towards greater recognition and appreciation of their work.

Dedeaux-Norris” art and journey leaves us with a simple yet profound truth: art is not just a reflection of the world—it is a force that can change it.

* * *

Works Cited

1. Tatum, Charlie. “A Conversation with Tameka Norris a.k.a Meka Jean.” Temporary Art Review, July 14, 2017. https://temporaryartreview.com/a-conversation-with-tameka-norris-a-k-a-meka-jean/.

2. Weston, Charisse Pearlina. “Arts+Culture: Tameka Norris: How She Got Good.” David Shelton Gallery, October 1, 2015. https://davidsheltongallery.com/artists/detail/tameka_norris.

3. Ibid.

4. “Nerdfighteria Wiki – Become Someone Else: Tameka Norris: The Art Assignment.” Become Someone Else | Tameka Norris | The Art Assignment. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://nerdfighteria.info/v/lmNKc4-zLOA/. Quote was originally spoken by T.J. in her The Art Assignment interview published on February 5, 2015 which the cited article quotes in text.

5. “T.J. Dedeaux-Norris.” Jane Lombard Gallery. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.janelombardgallery.com/tj-dedeaux-norris. Written as part of T.J. Dedeaux-Norris artist statement.

6. Fletcher, Kanitra, “Untitled (Say Her Name)” artwork description, College of Fine Arts Landmarks. https://landmarks.utexas.edu/video-art/untitled-say-her-name

Black Lunch Table (BLT) is a radical archiving project. Their mission is to build a more complete understanding of cultural history by illuminating the stories of Black people and our shared stake in the world. They envision a future in which all of our histories are recorded and valued.

About the author: Amoye Favour is a poet, a freelance writer and a lover of humanity. A writer by heart, Amoye Favour loves to write on topics that have humanity as its center. When he is not writing scripts, essays or articles, he is somewhere playing chess. He is a lover of God and is currently based out of Lagos, Nigeria. He can be reached out via X at his handle- @amoyef.

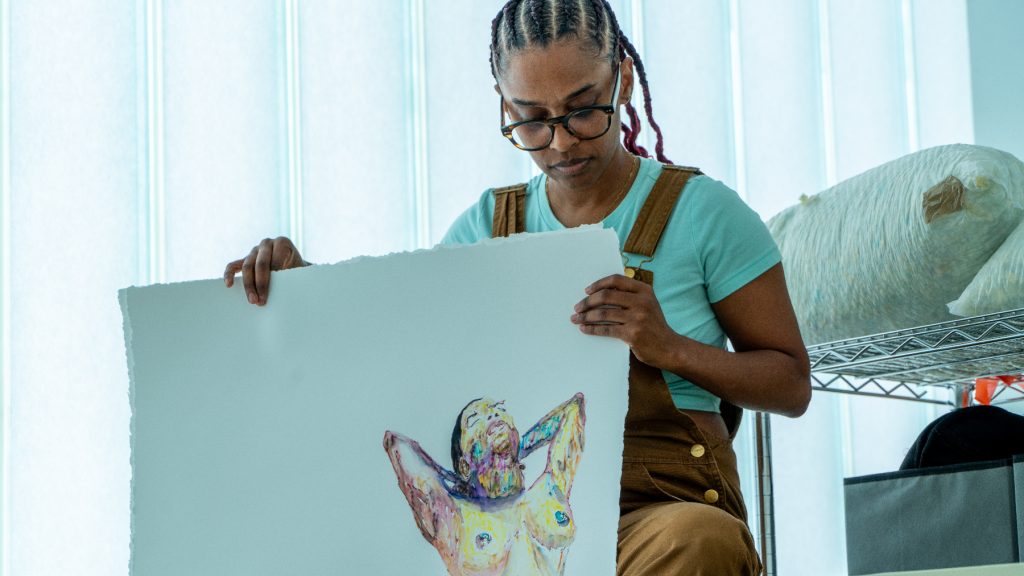

About the photographer: Ian Carstens (he/him) is a writer, filmmaker and curator based in the Midwest. His work explores temporality, non-human aliveness, multiplicity, as well as critiques of the archive, lens-based art forms and cultural institutions. He is the lead curator/filmmaker of Glass Breakfast, an ongoing archival project. His work has been published with Burnaway, Sugarcane, The Pulp, Ruckus Journal, Fugue Literary Journal and Sixty Inches From Center.