Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD) describes themselves “an undocumented-led group that organizes against deportations, detention, criminalization, and incarceration of Black, brown, and immigrant communities in Chicago and surrounding areas. Through grassroots organizing, legal and policy work, direct action and civil disobedience, and cross-movement building, we aim to defend our communities, challenge the institutions that target and dehumanize us, and build collective power. We fight alongside families and individuals challenging these systems to create an environment for our communities to thrive, work, and organize with happiness and without fear.”

OCAD was born in 2013 as a natural evolution from the founders’ early days leading what was then known as Immigrant Youth Justice League. I spoke with one of those founders, community organizer Reyna Wences, about her decade-long fight to transform policy and protect immigrants in Chicago. We also talked about the role of art in OCAD campaigns. Everything from banner drops to protest signs to public murals have played a role in building the immigrant rights movement in Little Village and beyond. Reyna talked about that legacy and the future of OCAD’s work in our interview.

Reyna Wences: What we [OCAD] wanted to do was kind of fill a gap, or create something that would address a community that was not being listened to or supported by other community organizations in the area. One of the first cases we took was [name redacted], detained in the suburbs. There had been police and ICE collaboration in that case. Then [name redacted] who was detained in Albany Park after his apartment complex got raided. So then we started hearing about all these, like people right, and they were willing to fight their cases. And so OCAD has, since 2013, we’ve had like three main focuses. One of them being the case-by-case work, so we’re not an organization that has an office and we’re not centralized in one specific neighborhood. But a lot of the people in OCAD grew up or live in Little Village, so that’s one big neighborhood where we concentrate, and then another one being Back of the Yards and Albany Park, right? And so then our work, because we’re not a centralized organization in one neighborhood, what we do is support people throughout the city with their deportation cases, and through the case-by-case work.

And that helps us in a couple of ways ‘cause one, we are able, by doing the case-by-case work, we get a better understanding of how ICE is operating and implementing new technology or policies, right? Their procedures and how they carry out raids. So for example in the case of [name redacted] that was raided in Albany Park, we didn’t know at the time that ICE was using this tactic of coming up to people’s homes with a picture of another person, a black man, saying that they were looking for that person, as an excuse to walk into people’s homes. Right? So playing into that like you know prejudice in our communities, like definitely capitalizing on the divide, you know the Black and brown divide that there can be sometimes. And so ICE agents were actively doing this back in 2013.

Additionally, through the case-by-case work we’ve also found out about ICE using biometric devices, so it’s just like a way of knowing how they’re operating and keeping an eye on them. And at the same time it also gives us a better sense of the way that immigration court is operating. And so we definitely do case-by-case work because it influences and informs the campaigns that we’re also being a part of.

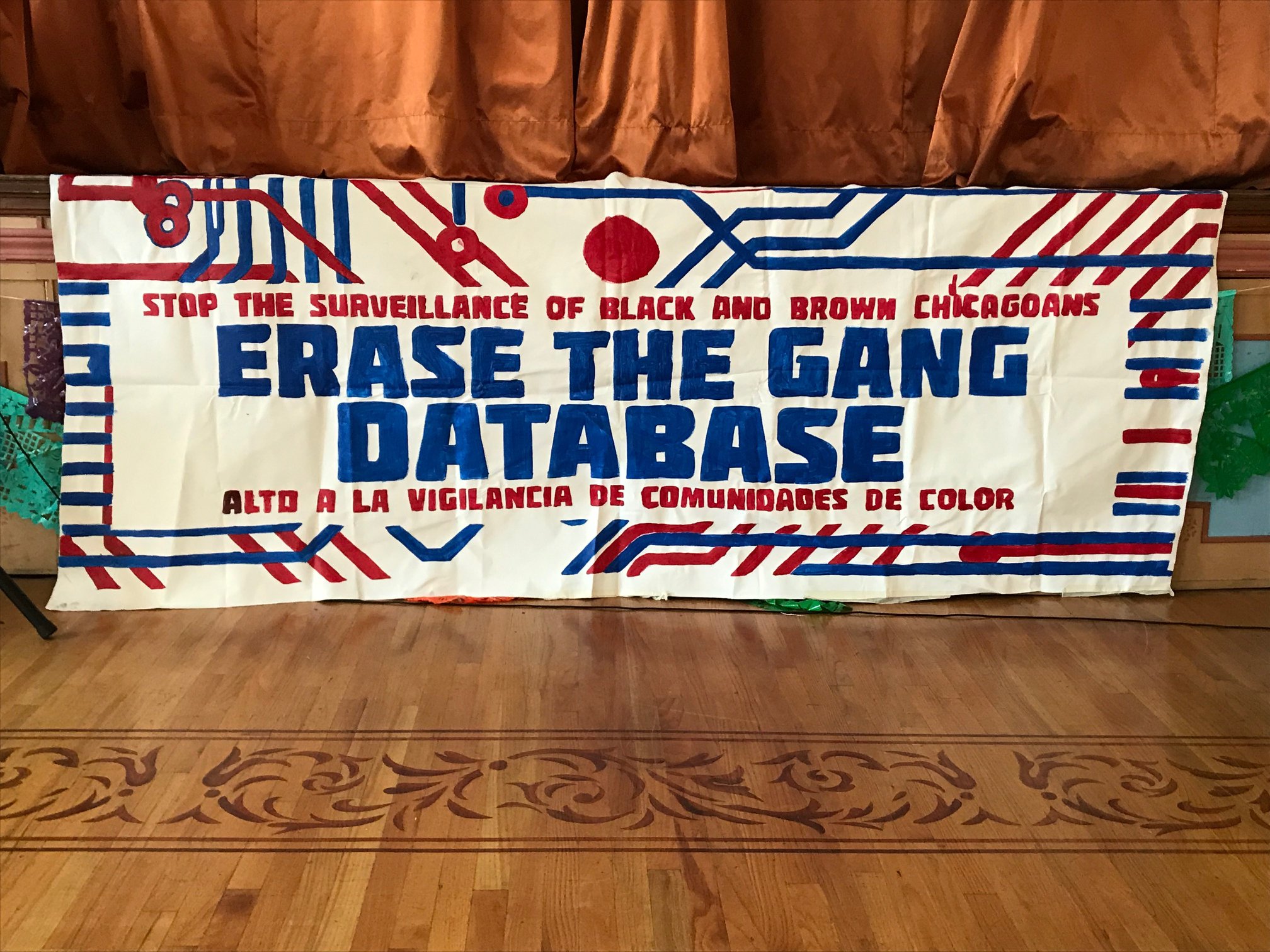

So for example the gang database campaign, they’re trying to Erase the Database. As OCAD we became involved initially because a person was detained in the Back of the Yards and he was put in the gang database and then ICE came to detain him, you know OCAD came in to support the family and through that campaign we learned more about the gang database. And now we know that it’s this list of hundreds of people predominantly from the Black community. And so our work has been a little bit of that, of like doing the case-by-case, but also actively either engaging in campaigns that are happening already in the city with organization that align with our values, or supporting the creation of campaigns that will extend sanctuary, not just for the immigrant community, but for other communities as well. And so here in Little Village, that has looked various different ways. OCAD has had a presence here in the sense of like “Do you know your rights” workshops, partnering up with organizations in the area to do some of that work as well, or to plug into some of the campaigns, or ask them to plug into some of our campaigns.

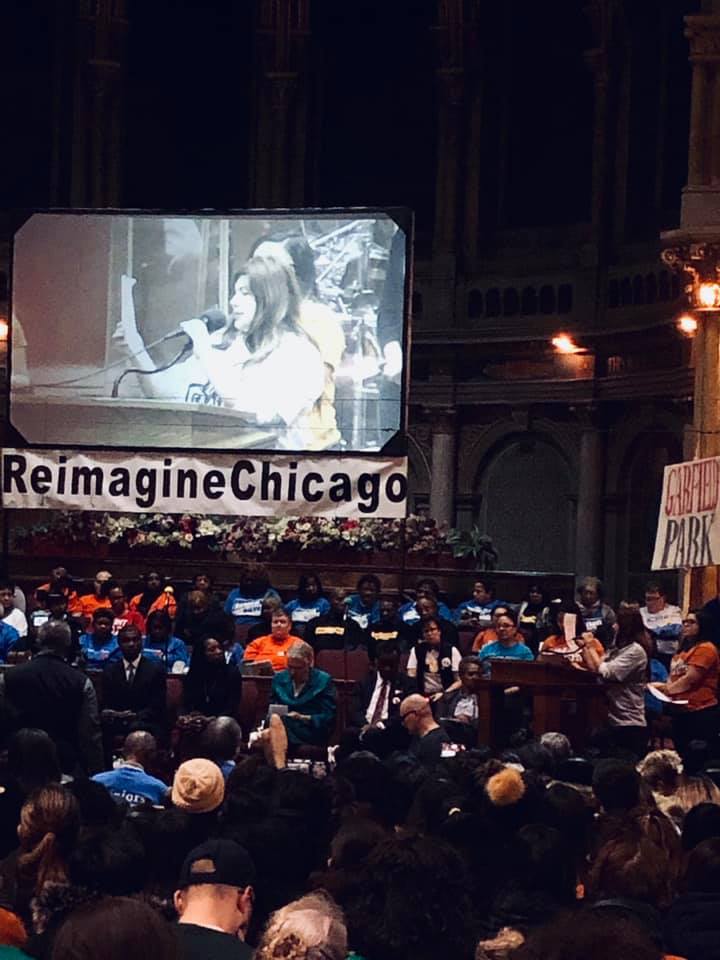

Last year I think one of my — I think that the biggest accomplishments that OCAD was a part of here in Little Village, was facilitating and being kind of like also the organization that helped put together Dyke March, the first Dyke March here in Chicago and Little Village, last year, or just a few years ago, when it started. So I think that that’s also been a role of ours, we don’t see ourselves as only an organization that does immigration work, although deportation defense work, that is like one of our strengths. But whenever we are able to make the intersections, and support other intersectional work then we’re there to do it. Yeah so that stops there. I think that’s like my OCAD spiel.

Anjali Misra: You mentioned not just being about deportation work and immigration work, but also working with other community groups and possibly other communities. Has there been a lot of inter-community solidarity or is this kind of work very neighborhood-based?

RW: Yeah I think it’s been a combination of both. So myself and maybe — let me see — me, Arianna Salgado, maybe like 8 to 9 members of OCAD live in Little Village. We’re dispersed throughout Little Village and so what that has looked like is by, you know, in the case of Dyke March, we knew that Dyke March was an effort that moves every two years, because some of us are queer or have been involved in Dyke March somewhat. And so it just kind of happened organically too where it was like, Dyke March is moving to this place is like thinking about another location, what are those neighborhoods where we could go? And you know some of us who were queer were like, yeah why don’t we explore having it in Little Village. So I think the collaboration to the extent in Little Village and OCAD has been also about being respectful of other organizations that are in the area specifically because we’re also not so like hyper-neighborhood, I would say.

So that’s why we definitely are around, but we try to I think we try to be conscious of you know, making sure that we’re not replicating work that another organization is doing and being like, “Yeah, we’re the only ones doing it,” you know? I would feel horrible if somebody did that to OCAD and so we try not to do that, you know?

The other thing I think where it’s more clear to me, at least, is commissions and inter-community work that’s happening. The campaign-based work and with the Black community, specifically, and so like I said with the Erase the Database campaign, once OCAD started finding out more about this gang database and the fact that it was predominantly the Black community, of course, we’re not as a Latinx-led organization at this point, we’re not going to take the lead and ownership of a campaign that impacts our community, but is not impacting it in the way that it’s impacting the Black community.

And I think it was just so organically based on relationships that we had had with members of BYP 100, specifically. This is something that we’re starting to find out about, what do we do about it, right? What do you all want to do about it? And so the campaign to Erase the Database has also been a beautiful thing because both organizing and academia has come together in a way that I hadn’t seen in before here in Chicago, at least in the work that I’ve been personally doing. In the sense that you have a group at UIC of students, sociologists of different fields, and professors that are actively not only trying to obtain information but analyzing information that then can be interpreted and used by organizations on the ground that are doing that work. And that, to me, like if we hadn’t had that resource from UIC, I don’t know that our arguments would be as strong as they are right now. And being able to paint the whole picture of what we know so far about the gang database. So I think some of these relationships and community and inter-community work is definitely based on the values, the goals of that campaign but I think it also has come down a lot to those relationships, personal relationships that people have.

AM: Yeah, absolutely. There has been a hesitation to work with major universities or institutions, because then you’re never sure what is their long-term goal or their motive. So it’s great to have those personal connections, it’s true. So for my next question, I’m wondering if, in your campaign-based work, does art play a major role in terms of strategy or even raising awareness?

RW: Yeah that’s a good question. And actually, yeah, so since, I mean, I guess, and I’m just going to be blunt in the sense that I don’t consider myself an artistic person or as an individual that knows what is art and what is not art, you know, I think that the word “art” also has a lot of meaning. So with that being said I’m like, of course we try and include art because we’ve had our banners, we’ve had our signs, we have flyers, and things like that.

So I think that like I just want to say and I think that the question goes beyond just like what materials we’re producing, I think it’s a question around being intentional and engaging and maybe using art as a way of cultural organizing, which is actually what we’re trying to do now. So whereas, yes, art has been a thing that has been present in OCAD organizing, whether that be through our direct actions, when we’re putting banners together, or when we’re trying to do theater of the oppressed type of stuff. Those things are — it comes up, I think that it’s just like other fields like in communications, it tends to get silenced. Or it becomes an afterthought.

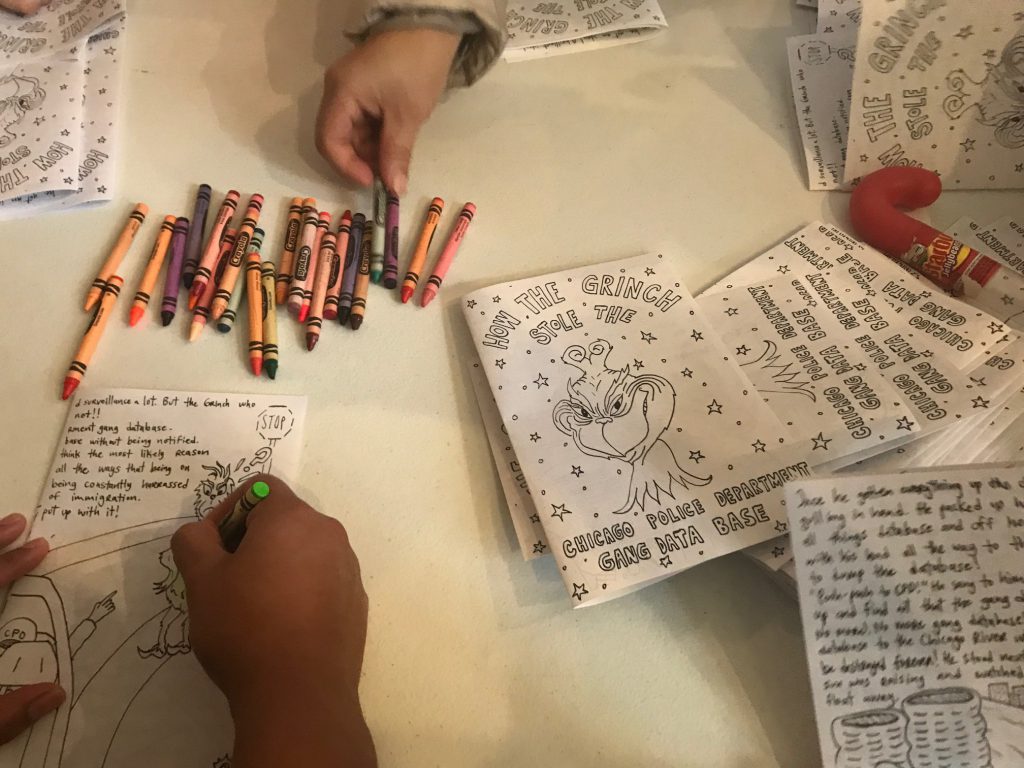

I mean, and I’m going to be honest, as an organizer, I’m just on the go, go, go, go, go. And this is a critique of myself cause I’m like I’ll go, go, go, go, go, let’s get this event together! And then without thinking about the art component or the visuals or the cultural, I just want to get this event done. And so everything else becomes an afterthought, right? The communications, the messaging. So to that I will say we are trying to be more intentional in using art as a way to push to change the narrative and to do more of that cultural shifting, particularly with the gang database I would say. We’re engaging in a campaign where the word “gang” is politically charged, where there’s been various indications about what that can mean, about what it means to be in a gang. Although it’s not a crime. But what we’re doing is we’re trying to incorporate different practices and strategies, like tactics through art to engage us in conversations. And storytelling, which engages in conversations that are pushing us away from the stereotypes.

For example, I don’t know if this maybe I’m just going on a rant but in the summer we met with organizers from Creative Co-Resistance, out in California. They did a lot of work you know around gang injunctions that’s in that state. And one of the things that they were saying is that one, their campaign was like three years long. And that throughout a lot of those years they had to rethink about the way there were engaging in communities. Not just about putting a teach-in together, but they were thinking of “How do we change the culture in our communities to talk about this?” Right? And so what they started doing is they started — they reinvented block parties. So yeah it was like, come to a block party! But the block party instead of having let’s say your usual block party activities, you have your activities be about the campaign.

And so that’s sort of what we’re trying to do here, we’re trying to incorporate for example now that the holidays are coming up, we’re going to have this holiday — like a holiday party, and we were thinking what are, how can we shift this the next couple — like the end of the year, to talk about the campaign. How can we frame it in a way where we can talk about that campaign and have maybe people be more open to coming to the space. And so then we started thinking of having this like, The Grinch Stole the Database. And to talk about how the Grinch, cause you know the story of the Grinch, right? The problem is not the Grinch, the problem is the people, and that people were like so, you know into Christmas for the wrong reasons. Right? And so we’re talking about the Grinch as this person that is an outcast from society, right? And so, we’re like playing around with how do we shift the story to make it about the gang database and how do we make those connections there?

AM: I wonder if you all are planning campaigns or projects for the New Year 2019 that you all are ready to talk about?

RW: Yeah, I mean right now the campaign to Erase the Database is still ongoing. There is an ordinance that has co-sponsors in city council but it has not moved out of committee since the summer, and a lot of it has been just like back-and-forth right? Like the organizing has to happen, the advocacy. And then elections came over us, so we’re being told and were told already that no ordinances are going to pass. At least not this one, until next year. So in the meantime what we’re doing is we’re patiently waiting for the Office of Inspector General to release a report on their investigation that they did on the gang database. That’s supposed to come out some time this month. And then next month in I believe the 19th we are doing, and when I say “we,” I mean the OCAD plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the city, we’re due in court on the 19th. And we’re asking for court support basically for people to come out that day to make a lot of noise because the city wants to — the city’s asking the court to dismiss the lawsuit at this hearing. And so we’ll be hearing — we’ll know by then if this lawsuit is moving forward or not. So we got the lawsuit in January and then definitely picking up the ordinance conversations in February.

But in the meantime, as OCAD we’re — we’re not a 501(c)3, we’re not a 501(c)4, but we also cannot endorse nor, you know, come out against candidates, right? Those are the rules I guess we have to play by. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t, that we’re not — that doesn’t mean that we’re not going to be engaging in like a political education. Right? And so one of the things that we’re doing is working with our community members, most of the Assemblea, plugging into the elections in 2019. So we’ll definitely be reaching out to our alder-people to let them know that we’re still pushing for the ordinance to Erase the Database but also for the amendments to the Welcoming City ordinance. Because Chicago’s still not a sanctuary city.

AM: Is there anything else that you wanted to add before we conclude? Any ways that folks can get involved?

RW: Yeah actually, we do have open meetings every 1st and 3rd Saturday of the month. Assembleas, like I said, are open meetings. And then people can follow us on social media, can send either of those a message if folks want to get involved. Mostly we just do our Facebook page to keep people updated.

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured image: A large banner that says “Erase the Gang Database” rests against a stage with light brown satin curtains on hardwood floors that have a dark brown floral design. Taken at the Winter Community Party to #ErasetheDatabase. Photo by Analia Rodriguez.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.