When I asked Chicago-based arts and learning curriculum expert Arnie Aprill to sum up the Envisioning Justice initiative, he told me it was “about respecting the knowledge of [Chicago] communities, not paying service to project funders.” Since the launch of this city-wide initiative, Aprill has been asking the hard questions, like “how do communities build their own capacity for healthy living? How are these communities being disenfranchised?” The catalyst of disenfranchisement that the Envisioning Justice program sites are addressing is the criminal justice system. Aprill works closely with hub directors (community leaders co-facilitating place-based Envisioning Justice projects) to offer activities that empower youth and families with the knowledge, tools, and resources to define their own futures outside of the seemingly ever-present gaze of the criminal justice system in Chicago. From Aprill’s assessment, many West and South Side neighborhood leaders face an uphill battle to not have their communities’ health be defined by where they fall in mass incarceration statistics. Aprill has always seen his role as helping already established neighborhood programs build capacity to address the most pressing needs in their areas.

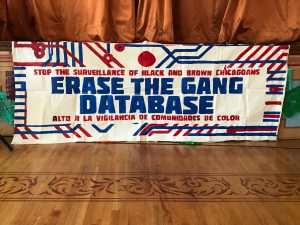

In his mind, the Envisioning Justice project’s primary mission is to confront how the criminal justice system operates across the city. While many Envisioning Justice activities focus on (in his words) “small fixes,” like providing young people with alternatives to incarceration through arts and learning, these isolated interventions are designed to add up to a paradigm shift in which communities can claim ownership and pride for doing the important work of shifting attitudes amongst their own neighbors. Aprill said he hopes that the ultimate outcome of Envisioning Justice will be for Chicago neighborhoods to espouse an internal sense of honor about the work they’re doing to combat oppression. “Envisioning Justice is about fixing the cultural ills that create the need for a prison system. Each hub does this in different ways. The theory of [the initiative] is to bring artists into alliance with community change agents to broaden possibilities for positive life options.”

Aprill identifies three main thrusts to the initiative: one is to provide support to site leadership, in the form of organizational capacity building; the second is to fund the engagement of teaching artists to provide classes at the sites; and the third stage is to “unearth powerful voices and build expressiveness in neighborhoods, rather than re-highlight art-activist celebrities.” While Aprill says the intentions in this final phase are “emergent,” he does see a culminating exhibit of the Envisioning Justice work as an opportunity to “stir the pot to change the discourse. This body of work [can be a part of] a broader project to change the discourse around criminal justice.”

With these large-scale goals in mind, Aprill said he also recognizes the need to support community organizations at the most foundational level. “These [organizers] are stressed but brave and persistent. They’re doing so many things, under so many pressures in very distressed neighborhoods.” Pointing to the intrinsically necessary nature of many of these space, like Open Center for the Arts in Little Village, Aprill notes that “CPS teachers come to Open Center when they train to work in La Villita, because it is a major community resource. Teachers also have a way to understand the neighborhood and become oriented here. Open Center has even turned their top floor into an exhibition space for the local high school art classes. But Open Center is not funded by CPS.” Throughout Aprill’s career as an arts and learning consultant, he said that time and again he’s witnessed organizations like Open Center for the Arts being asked to meet outsized neighborhood needs without the support they deserve. He sees his role as empowering organizers to thrive more effectively in the areas in which they already function.

He said his goal is to shift the social narrative away from disenfranchised communities as constant victims of oppression to astute “citizens with a lot to offer and negotiate around the barriers they face … [through Envisioning Justice] teaching artists become socially responsible change agents. That the initiative has been successful in such a short amount of time in building strong connective tissue between teaching artists and grassroots organizers is a source of pride for Aprill.

Featured image: Photo of the sculpture Flamingo by the artist Alexander Calder in Chicago’s Federal Plaza in front the Kluczynski Federal Building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. A red metal sculpture with sweeping lines stands in front of a black minimalist skyscraper. Photo by EdVetté Wilson Jones.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.