With our contemporary moment marked by ecocide, genocide, callousness, blindness, and apathy can we take time to look at a few pictures? Or what if we pause to recognize the images that make up “us”? The images all around us, ones that show others the “who” we want to be seen as or who they think we are. Images taken, consensually or not. I found myself walking through the wilting rose garden at the Des Moines Art Center with these questions. All from having just experienced Samantha Box’s profound works in two shows at the institution.

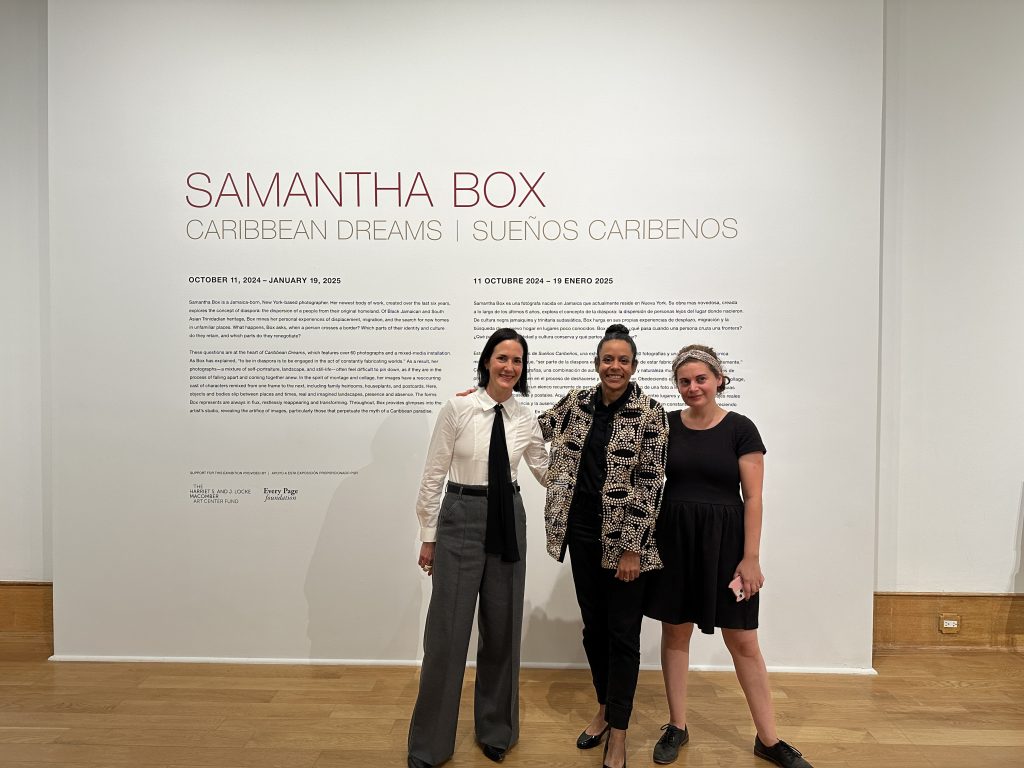

Up until early January 2025, Jamaica-born, New York-based photographer Samantha Box had artworks in two Des Moines Art Center spaces: a solo exhibition Caribbean Dreams as well as Minor Key. Both exhibitions featured Box’s work in conversation with the Des Moines Art Center’s permanent collections.

Iowa feels like a strange context to consider diasporas, identities rupturing and processes of un-pinning with such technically sharp works by Box. “Strangeness” here is but a root of colonial projects and present dehumanization via disconnection. If you let this work in, what is let out?

However, Box’s intentions are clear. They make images for themselves. While viewers bring their own baggage and perceptions to artwork, what can we ask of the artist who has already contributed so much? This question becomes especially pressing when considering the fungibility of Black bodies, the persistent presence of plantation economies, and the realities of the diaspora. I’m grateful to experience Box’s work in central Iowa. Even more so, I’m grateful for the artist who formed these images and then agreed to labor further to answer my questions. Quickly our conversation moved away from prescriptive interview dialogue and focused on Box’s deep expertise with both camera and image as tools. We spoke about how they navigate the ecosystems around their work and how an artist exists with autonomy. Box is not a food photographer. They don’t make still lifes for Dutch colonists nor do they make exotic Caribbean art for trendy colonists or Ian Flemming types. Box’s work speaks for itself—without a doubt—so our conversation became part talking shop and part theoretical questioning.

Samantha Box and I spoke over video chat in late October.

Right Image: A photograph of Samantha Box standing in front of Transplant Family Portrait, 2020 Digital collage printed as archival inkjet print, collaged with secondary archival inkjet print elements. Transplant Family Portrait features a collection of potted plants and various hues of pinks. Image courtesy of the Des Moines Art Center.

Ian Carstens: Your show Caribbean Dreams is in Des Moines where I’m based and it was my first time seeing your work in person. I’m struck by how experiencing your work here feels like somewhat of a survey and it’s marketed as your “first museum solo exhibition” but it also feels like a piece, a node. And this is partially because you’re showing multiple works simultaneously right? What does that do to the exhibition? Maybe it’s too soon to even think about that but why are there so many artworks in so many places at the same time? How does it impact the way your artwork should be seen or understood?

Samantha Box: Mia Laufer (formerly of the Des Moines Art Center) originally approached me and asked if we could do a solo exhibition of my work, Caribbean Dreams, and then Dr. Orin Zahra, curator of the show in DC (at the National Museum of Women in the Arts), who is a good friend of Mia’s—and they both went to grad school together—joined our conversation. The way we conceived of the show in Des Moines was that the main gallery space would be Caribbean Dreams; eventually, there was the idea of pairing works from my earlier documentary series The Invisible Archive with works from the permanent collection. This latter idea became “Minor Key” in the John Brady Print Gallery, where my images are not contextualized as a documentary project but rather more like the ground of an affect that we used to kind of guide us to create these relationships between the collection and my images. The show in DC is essentially half and half, Invisible Archive and Caribbean Dreams, and is an introduction to my practice, as over the past 20 years.

When everything is laid to bed entirely I think there’s certainly these things popping up for me: What is my work doing? Questions about legibility, questions about value. So there’s definitely going to be a reorientation after all is said and done, that I’m excited about. It’s not just where my pictures are going but also about how I want to speak about my work, and my relationship to photography and other things like that, it’s this sort of evolving moment.

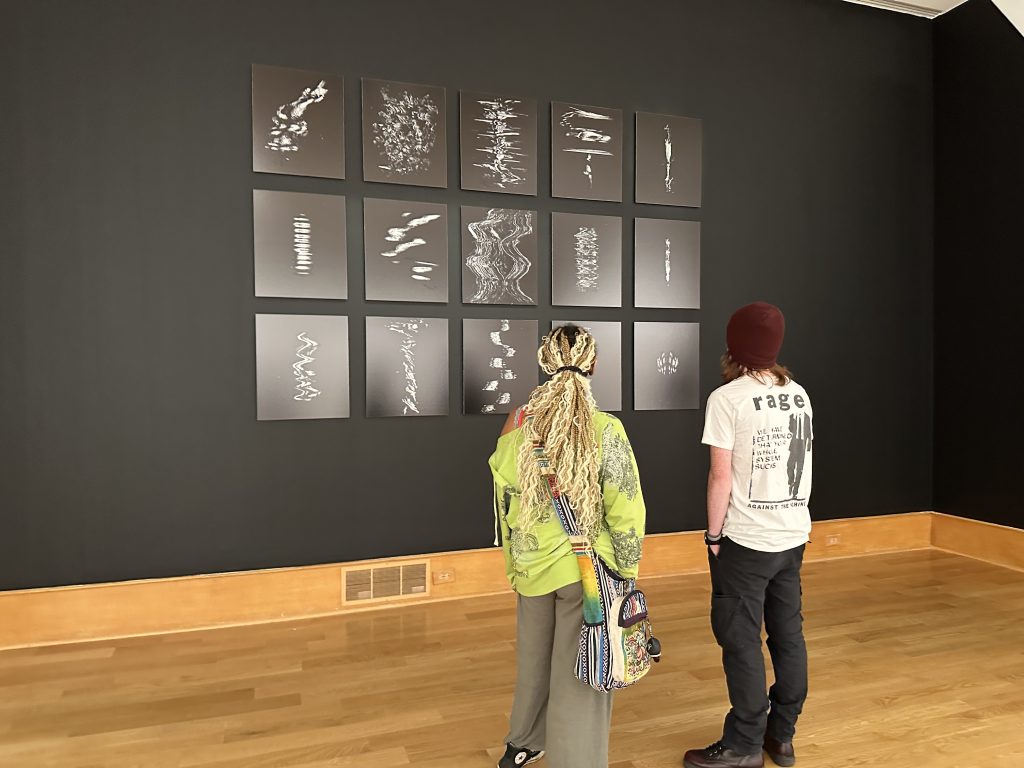

2021–ongoing. Archival inkjet prints. Image courtesy of the Des Moines Art Center.

IC: Could you tell me about your chosen tools and techniques with them? (Things I share in using with you, even to do this interview).

SB: Photography was something that, from the minute I took my first pictures I was enraptured by it. I was raised very much in the age of the printed photograph, in print media. When I started making pictures, I actually was much more interested in painting. I was studying Biology and I took some time off to see what this idea of being an artist was. I couldn’t take a painting class because you have to take drawing. I mean drawing is fun, but I actually find it to be incredibly frustrating and tedious in a way that I don’t enjoy. So I ended up taking a photography class and that was the thing that really clicked for me. It felt and it still feels very very right to look through the viewfinder and to compose or to organize the world in that way.

I was really fortunate that my first photo teacher was Shawn Walker. In addition to Shawn Walker, there were a number of other people at City College of New York who were considerate and thoughtful makers of images. I was imparted with this idea of what the image could do. One of the missions of Shawn Walker and the Kamoinge Collective—of which he was a founding member—was to stand against the ways in which Black people, especially Black people in Harlem, were being depicted. If you look at the breath, complexity and agency of the work of the Collective members, and you compare this to the ways in like Black people, Black people in Harlem, or just Black people living in cities, were depicted in White media versus like the breath of expression in these photographers, you realize this a power of what the image can do. As I grew as an image maker, I considered whose bodies and histories have been historically couched as the Other. And so: what does it mean for me to be making images, with the realization that my history and my body and my identities, as a Queer, immigrant Black woman who’s also multi-racial, has historically fallen on the side of being depicted through the gaze of the White middle-class male. Beyond the idea of refuting the gaze but really thinking about photography expansively and positioning those questions into the image. These questions aren’t perfect and there are definitely moments in which I too make mistakes. I can forget about the ways that these things function in photography. What does it mean to be a person who’s historically been the object of the image versus the maker of the image?

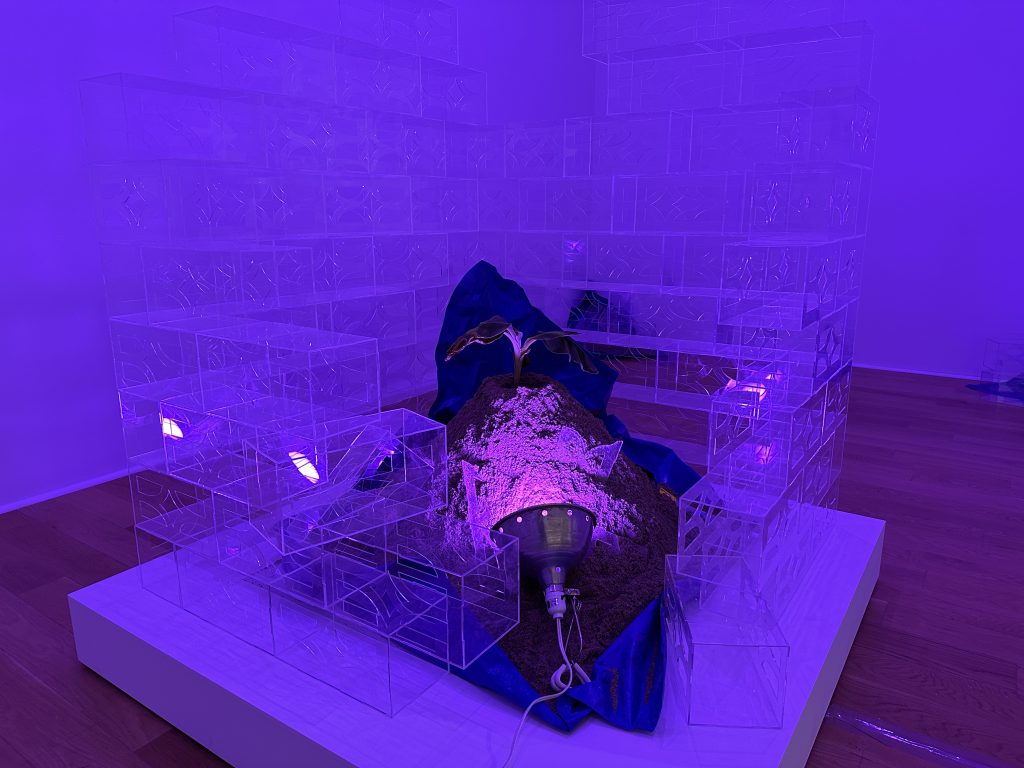

IC: That has me thinking about process. Also these spatial aspects: inside the frame, the frame, and then the context of where the image is. Thinking about layers of reading. Thinking of the UPC codes in your work Transplant Family Portrait that can be literally scanned but also how the still life can symbolically represent things and ideas, states of time, and decay. You also have living beings involved with your work, like plants, so there are conversations on aliveness too.

SB: I’m really interested in the idea of making a complicated image. A dense image. I think I’ve always been someone who is really interested in that. I’m asking and answering questions that are my questions, that come from my historic and lived experiences and thoughts about those experiences. As I’m making I’m packing all of those things into the image, and sometimes that means there are layers that happen in the overlays or a fracturing of the base image. These things that don’t create an easy read. I want to challenge how photography has a tendency to make things very legible. You have to navigate your way through my work; I like the idea of instability happening in my work. Some of that is the birth, growing, and decay cycle. Some of it is too many things happening, or overwhelming color. I want my images to feel as if they are moving and shifting. I think this counters how photography can feel and how it has been used.

You have to sit with these images. The Invisible Archive work was about overlapping systems that created multiple crises in the lives of at-risk and/or houseless queer and trans youth. With Caribbean Dreams, I am also talking about echoes of the past in the present. The more I can pack in, the better. It feels sometimes that these things are dizzying for me. I’m glad when that happens in the image.

IC: Could you say more about that packing? I am curious about before the art object, during the making and then after the art object is made. What are the processes or labors involved like? What labors are unnecessary or forced upon you or the work?

SB: I appreciate the question being asked in relation to labor, which is something I think alot about. Caribbean Dreams is in many ways about labor as value. The value placed on the bodies and knowledge and labor of the enslaved, the indentured, and the immigrant. One of the ways in which I am thinking about how to reposition my work is to expand its framework beyond explorations of one’s identity and my living in diaspora to encompass and to ultimately focus on questions of value and labor.

The Caribbean was and is a space where notions of race, notions of capitalism, notions of commodity were and are formed and spread out to the rest of the world. All of these things are still going out. Connecting it to the still life, the objects in these paintings had value delineated by an empire; see the Black human was couched as an object. How do I push and pull against that? The image teaches us to covet, to want and I’m trying to twist things, to bring forth the question of what is value, who is valued, in relation to the Caribbean, the commodification of its people, land, labor, and knowledge. How do I translate that into the image?

I often get questions about process. And this isn’t necessarily a dig at you Ian, but I get asked this a lot. Most of the people who ask me this question tend to be men. I think about this a few ways. The process of my making this work—it’s a lot. What I mean by that is I’ll often have an idea and I’ll sketch it out, or I’ll make a note. Then I go into the studio and then as I’m working other things will happen. Sometimes the picture turns into the picture, sometimes the picture is not the picture. Sometimes I’m bringing things together that don’t work out. Sometimes accidents happen. Some images happen on the way to other images. Then there is a series of questions afterward, sometimes for years, months, and days afterward. There’s a process but it’s the process of just being in the studio and working. This process question is fascinating to me because this process happens in other spaces—physical, intellectual, emotional—where sometimes I even surprise myself. The process question seems to say “oh they’re just objects, there’s got to be a formula to put these objects together, to make it happen.’ It’s just…no. There’s this engagement not only with the idea but with the work, to see it all the way out.

IC: This reminds me of what you said about the artist statement too. You’ve already put in the work to say what you are saying. So if I ask you further about process, it’s saying that I want more labor from you. And can I display that I see you as a source of potential labor, on my terms for my benefit of understanding.

SB: There is an equivalent question with documentary photography, and one I got a lot when I was making Invisible Archive. “Did you have persimmon to make these pictures?” Obviously, it’s being asked to check for consent, which are good, but the subtext is “do I then have permission to look at these pictures without an uncomplicated gaze, a gaze where I don’t have to implicate myself?” The process question, like this, is a question of additional labor; frankly, would you ask a White guy for this additional labor? Or assume that one could ask? Again, regarding the documentary work, people will also ask “how did you come to make this specific image?” And I’ll say it took years. Yes, it was one moment, but it was years of being involved. Sometimes it takes years to be able to read someone’s face to know when the right picture is happening. That’s not really the answer people want.

I do think there is something about my own subjective experience, my ways of looking at the world, of handling materials, and my magpie-like tendencies. They all add up to something that is not a clean answer. None of this is clean. I’m trying to articulate something that has so many layers, feeling, emotion, history, and fucked up shit. To rebuild, to reconsider what it is that I am doing. To come back to things. That’s the heart of it. There is this constant churn and that’s how it all comes together.

IC: I’m thinking about language systems and language tools. Thinking that a name, a label, an image fixes something in space and time and value and objectness. A fixedness of meaning. But what you’re saying is much more open than that.

SB: Some of those things are a bid: make your life legible to me. Why is it that I have to explain myself or my histories in this way, in which for example, there isn’t a didactic wall label, say Picasso? So in a way that request is one that is otherizing, the subtext of which is “I don’t have the framework to understand that/your life/your histories” And I think, well why don’t you? But you have the framework to understand Jackson Pollock? Coupled with questions about my process of making, what those bids for legibility are is: tell me why these things are important. What is the value of you, of your work, of these objects?

How much do I want to explain? You too can do the work.

Yes, the artist is in service. But I’m not in service to you, I’m in service to my ideas.

About the author: Ian Carstens (he/him) is a writer, filmmaker and curator based in the Midwest. His work explores temporality, non-human aliveness, multiplicity, as well as critiques of the archive, lens-based art forms and cultural institutions. He is the lead curator/filmmaker of Glass Breakfast, an ongoing archival project. His video works have screened at various festivals as well as on public television. His writing has been published with Burnaway, Sugarcane, The Pulp, Ruckus Journal, Fugue Literary Journal, and Sixty Inches From Center.