This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

During one of my first weeks in Chicago, on the way back from exploring Jackson Park (my new local park, and coincidentally the city’s second largest green space), I picked up a thick tome from a Little Free Library: environmental historian William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis (1991). In the book’s opening paragraphs, Cronon writes that “no city played a more important role in shaping the landscape and economy of the midcontinent during the second half of the nineteenth century than Chicago.” Landscape and economy, hand in hand, are described as the underlying forces (often at odds) out of which urban life in Chicago emerges. Myth of The Organic City at 6018|North takes us on a winding journey extending Cronon’s thesis, moving from pre-colonial history to destructive industrialization and ending with current-day environmental initiatives that aim to reach a more harmonic balance in the complex union of “the city” and “the wild.”

The exhibition is divided into three sections which evolve naturally from one to the next as you climb from first to third floor. The exhibition’s first floor, titled Land Usage: From Sediment to Settlement to Steel, presents a historical overview of Chicago’s land and its development, from the pre-settlement era to the present. The second floor, Waterways and Land Mess, has several rooms with multimedia experiences focusing on water and atmospheric pollution in particular. The third floor, Regeneration, centers various efforts to improve city life from an environmental perspective, beginning with early eco-activist movements in the 1960s through recent and ongoing projects.

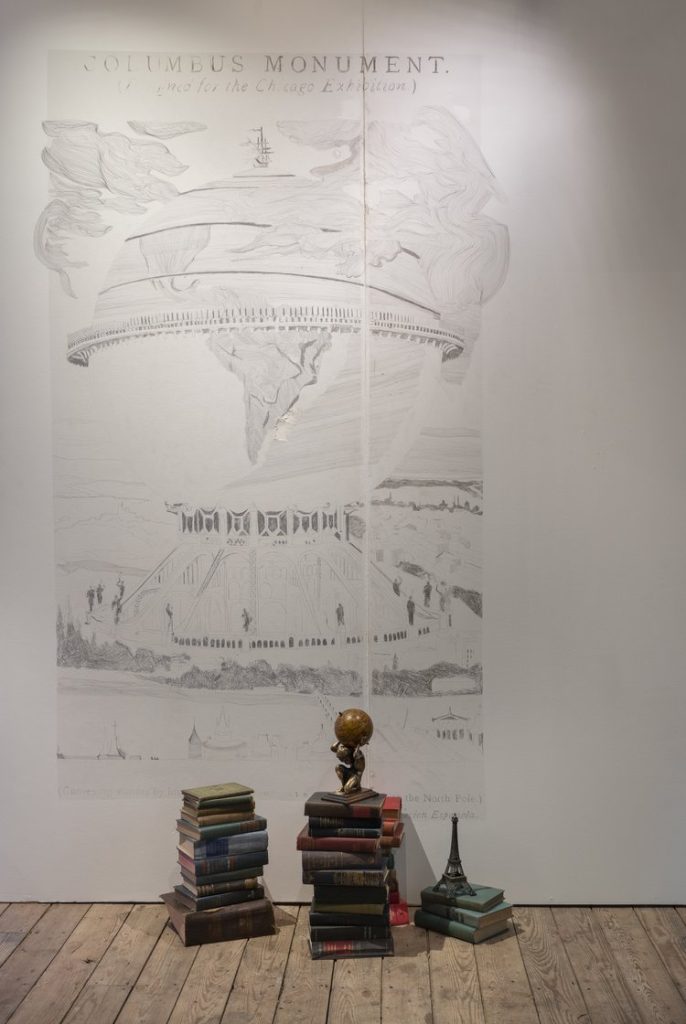

On the ground floor of the gallery, 6018|North’s already unique weathered quality—the building is a dilapidated Edgewater mansion, a far cry from “the white cube” or polished museum wing—is heightened by the sense that organic material is trying to push through the walls. From installations using flower pigment, rain and snail shells (Pierre-Alexandre Savracouty’s D-4A), to layers of dirt rising from the ground (Luftwerk’s Extraction), several rooms on this level feel as though natural history is invading the home, grasping at openings to “rewild” the space. This section of the exhibition tells the city’s history from an environmental perspective with the aid of archival pieces referencing colonial projects, pre-settlement vegetation maps, and vintage land surveys from when the city was mainly swamp and woods. Emilio Rojas’ Memorial to an Unbuilt Monument and/or A Litany of Reduction is particularly striking. The piece depicts the award-winning design of a building called “World of Iron” which was almost constructed for the Columbian Exposition in 1893. Rojas’ relief shows the grand scale at which 19th-century settlers imagined human engineering could transcend the facts of nature. While the design was celebrated, it was never constructed due to engineering concerns. The architectural plan, topped by an iron globe, showed Columbus’ journey to “discover” America, placing colonization on a massive, literal pedestal which would have cast a looming shadow over the surrounding land.

Time spent on this floor is punctuated by the brash noise of Aleksandra Walaszek’s kinetic installation, And If This Is Home, Welcome Home (2024). Consisting of an automated set of steel blinds, this sculpture periodically makes a harsh, metallic rippling sound as the blinds change direction. The steel curtain is awkwardly placed in the middle of the room, serving as a hostile, but ineffective dividing border. A white blinds rod is part of the sculpture, giving us the false idea that we might be able to stop the clamor or manipulate the movement of the blinds. The clashing noise of manufactured metal is especially disconcerting, as it accompanies nearby pieces that address how disruptive manmade processes are to the environment.

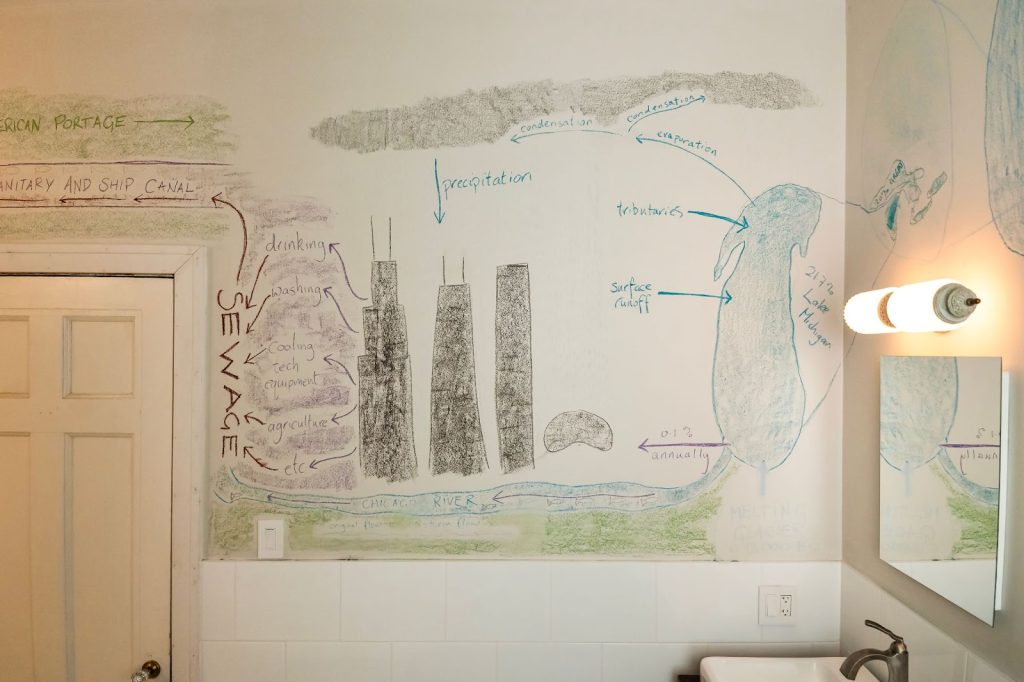

A remarkable aspect of 6018|North as a venue is that even within transitional moments such as stopping by the restroom or navigating the creaky staircases between floors, you never actually stop seeing the exhibition—there are pieces installed on nearly every wall surface. Eugenia Chang’s You Are Here: Where is Your Sewage Going (2023) is a perfect example—even while washing your hands, your mind can’t zone out and wander from Chicago’s urban infrastructure as you stare at a chalk-drawn flowchart of the city’s waste management system.

On the second floor of the exhibition, we move into an exploration of human impact on the city’s natural environment. Some works, like Shane DuBay and Carl Fuldner’s series Plume, document change as it manifests in nature. In this line of photographs, bird specimens collected more or less a century apart are photographed side by side. The images show the extent to which air quality has drastically improved, since the city’s economy, and by extension, the landscape, have moved away from soot-producing factories. These works together point to the importance of centering the non-human in economic histories. To quote Cronon, who shaped my early understanding of Chicago’s landscape: if we only tell a human-centered story of our city, “we miss the extent to which the city’s inhabitants continue to rely as much on the nonhuman world as they do on each other…we also wall ourselves off from the broader ecosystems which contain our urban homes.”

The exhibition’s third floor explores efforts to address environmental issues as a sort of balm to the damage highlighted in the first two levels. For example, JI Yang’s video installation, wild mile in action (2024), documents the installation of a floating eco-park in Chicago. The innovative Wild Mile project aims to turn urban waterways like the Chicago River into nature sanctuaries (and could be an inspiration globally for more like it). Yang’s work is a real engagement with optimism and earnest hopefulness moving forward with eco-activism, which was particularly relieving after having seen works detailing industrial pollution of the same river (like Matthew Kaplan’s photograph, Barge loading on Calumet River near Sulfur Plant, 2019 and Jane Buyck’s documentation of the river’s unglamorous contemporary usage in the video installation Chicago par ses riviéres / Chicago by its rivers, 2023) on the floor just below.

As you reach the top of 6018|North, the nature of a three-story walk-up mansion from the early twentieth century means that you will need to walk back down through a maze of the same art from a different angle down the rear staircase, contemplating what you saw earlier in light of the rest of the exhibition. This venue in particular as a home for an exhibition about the city’s position in environmental history is especially fitting. Constructed in 1909, the building has witnessed many of the industrial waves and evolutions covered in the exhibition, and several times sustained damage from floods and other natural disasters. Neither the venue nor its patrons exist outside of the city’s natural and built environments: the exhibition is about our history, and ends with a question of how to live differently for a more sustainable future. Myth of the Organic City challenges us to think in terms of deep ecology about the webs we inhabit with the land, the nonhuman, the rickety buildings, the new eco-parks, the potential future initiatives, and each other.

The exhibition is far too vast to engage with all of the 30+ artists involved, but this review would like to acknowledge Alexandra Antoine, Rebecca Beachy with Nina Barnett and Christine Wallers, Jennifer Buyck, Julie Carpenter with Jane Norling, Eugenia Cheng, Carl Fuldner and Shane DuBay, Iker Gil, Brian Holmes and Jeremy Bolen, Candace Hunter, Matthew Kaplan, Stephen Lowell Swanberg, Jenny Kendler and Giovanni Aloi, Nance Klehm, Haerim Lee, JeeYeun Lee, Jin Lee, Nathan Lewis, Stephen Lowell Swanberg, Luftwerk, Jenny McBride, Meida Teresa McNeal, Sherwin Ovid, Viet Phan, Melissa Potter, Emilio Rojas, Pierre-Alexandre Savracouty, Tria Smith and Katrin Schnabl, Deborah Stratman, Jan Tichy, Aleksandra Walaszek, Rhonda Wheatley, Amanda Williams, JI Yang, Sangwoo Yoo, and others.

“Myth of the Organic City” is presented as part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaborative initiative organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The exhibition is among more than 35 Art Design Chicago exhibitions that highlight Chicago’s unique artistic heritage and creative communities.

About the author: Mrittika Ghosh (she/her) is a Bengali-American reader, journalist, and communications strategist currently based in Chicago. She holds a BA from Mount Holyoke College and an MA from the University of Chicago, where her focus was on migration and queerness in Francophone and South Asian contexts. She is a member of the Muña Art Writing Residency’s 2024 cohort, and has also been a bookseller, educator, and translator.