As I approach my two year anniversary as a resident of Missouri, I find myself reflecting on how my decision to move here has derailed at least seven generations of a lineage rooted in Texas.

In the summer of 2022, I loaded all of my belongings (and my two-year-old pup) into a U-Haul truck and drove from Houston to Kansas City. The surface-level explanation for my spontaneous move is that I followed an employment opportunity. But the more nuanced reason is that something inside me—perhaps a voice from the ancestors or my own intuition—decided that my purpose was better served beyond the state I had known my entire life. My reflections filter through joyful emotions like confidence in the person I am becoming, but they are also clouded by grief for the close proximity to my family that I relinquished on that long one-way road trip.

Call it fate, or just a plain coincidence, but the opening of Threshold II: Migration Patterns deepened these timely reflections in many unexpected ways.

As I ascend stairs to the entrance of the exhibition space, I am greeted by the voice of civil rights leader and Black nationalist, Malcom X. Permeating through a glass vitrine filled with soil and muffled by an oak lid atop an upturned cheerleader horn, he dictates, “…You can’t hate the roots of the tree and not hate the tree. You can’t hate your origin and not end up hating yourself.”

The audio excerpt comes from a speech titled “Confronting White Oppression” given by Malcolm X in Detroit, Michigan on February 14, 1965. The speech is one of his last public appearances before his murder, one week later.

This assemblage by Kevin Demery, consisting of glass, soil, wood, and sound, rests on a vintage coffin bier sized for a child and evokes an early Victorian practice of placing devices that amplify sound on top of graves so that if you were accidentally buried alive, you could call for help. The audio component in Can You see this Face Covered in the Maps of Dead Nations is purposefully muffled, forcing the viewer to listen intently until the words become clear and impossible to unhear. Through this work, Malcolm’s teachings are projected beyond the grave and into the minds and hearts of all who come into contact with it.

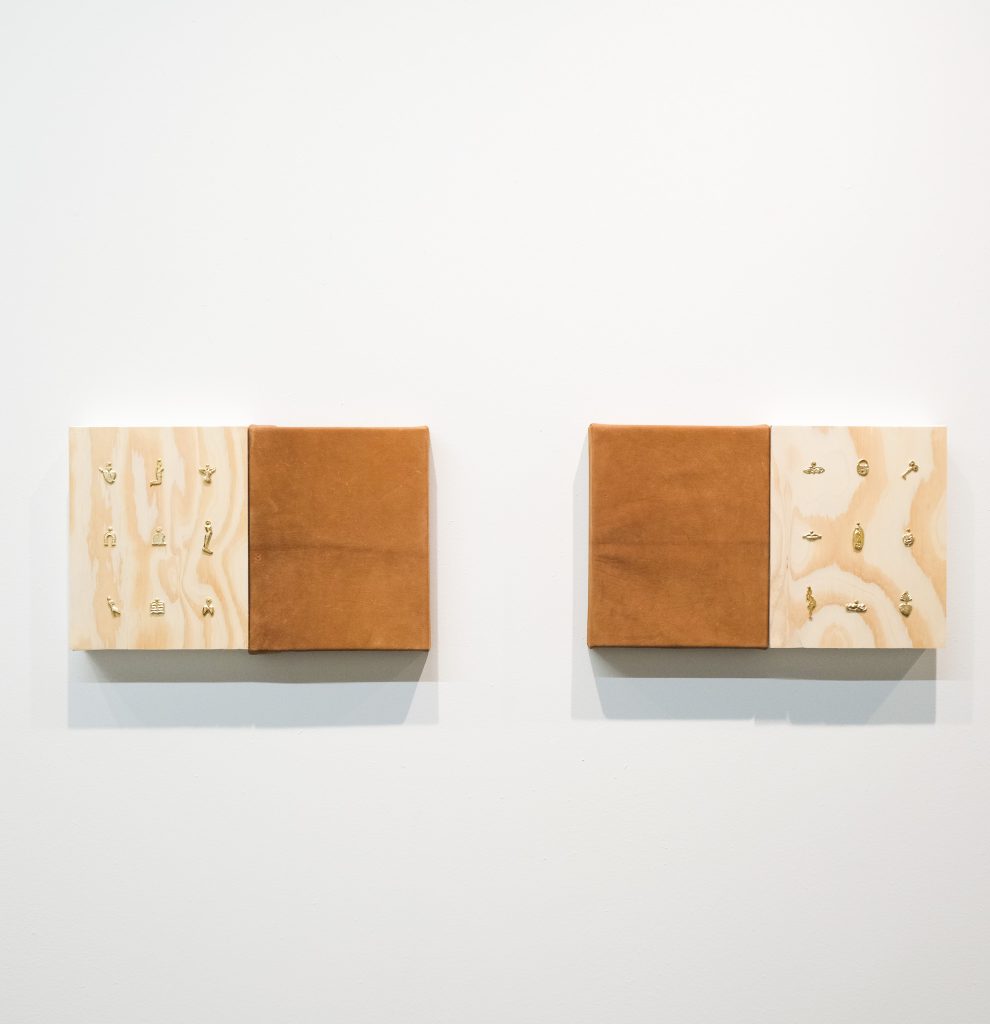

On the wall nearby hangs Andrew Mcilvaine’s When the Hummingbird Sings and When the Eagle Leaves, works crafted from buckskin and gold milagros mounted to sheathing and canvas. The milagros, small charms typically used to adorn altars and shrines, give reverence to the symbolism of death in Demery’s work.

These works are some of the first things you encounter in Threshold II: Migration Patterns, the second collaboration in an ongoing series by artists Andrew Mcilvaine (born 1993, San Antonio, TX) and Kevin Demery (born 1992, Modesto, CA). The first iteration, titled Threshold, premiered in August 2023 at Vulpes Bastille, an artist-run gallery in the East Crossroads area of Kansas City, Missouri. Through multi-media assemblages, the first collaboration investigated the conscious and unconscious barriers—or thresholds—that lay at the intersections of Black and Latino cultural experiences in America.

The current iteration, on view at Gallery Bogart in the West Bottoms neighborhood of Kansas City, Missouri, continues this multi-layered conversation, with a focus on how the artists’ lineage and histories have shaped their migratory experiences from Texas and California to the Midwest.

Materiality is an essential pillar of the artistic practice of both Kansas City-based artists. Their use of materials such as soil, sand, wood, and found objects create complex visual metaphors that defy one-dimensional assumptions placed on Black and Brown bodies.

Through installation, assemblage, and word-play, each artist reveals what lays behind the silhouettes of Blackness and Brownness. They collaborate to interrogate their journeys to overcoming the poverty and political inertia that shaped their childhoods.

In many of his works, Demery utilizes oak, a material commonly used to build coffins, and pine, representative of one of the most commonly found trees relative to the San Francisco Bay area, where he grew up. Commonly used as roofing material in Latin American architecture, Mcilvaine utilizes terracotta as a vessel for holding memory in a series of six wall-based relics. A crown of thorns, flames, an ear, a broken bone, and an axle each tell the story of his experiences with religion, low-rider culture, oral histories and a fond love for skateboarding.

The North American migratory pattern of the monarch butterfly is such that it takes three generations to travel from its primary home in Mexico to its final breeding ground in Canada. The third generation, however, has the ability to produce offspring that migrate from Canada all the way back to Mexico in one generation.

When the Tumbleweed Sits meditates on the motif of migration. Rehydrated monarch butterfly specimens adorn a brown wooden chair on a pedestal of rippled cathedral glass. A large Texas tumbleweed and layer of sand sit in the chair, overlooking a book detailing Indigenous-Mexican histories laying at the foot of the chair. This assemblage, reflective of Andrew Mcilvaine’s relationship with multi-generational migration from Mexico to Texas to Missouri, reminding viewers of the privilege knowing our personal lineage grants us. The tumbleweed, a plant commonly associated as an icon of the American West, detaches from its root system when it matures, allowing itself to roll wherever the wind carries it, dispersing its seeds along its journey. Mcilvaine compares the tumbleweed’s stagnance in his installation to his ability to embrace a stillness his elders have never known.

Embedded into conversations about migratory patterns, Demery challenges viewers to consider the cognitive dissonance between the sanctity of the Black body in relation to the sanctity of game animals. In Buck, he mounts the silhouette of an unknown Black man taken from a barbershop poster to a blue police shield. Above the silhouette hang the antlers of a white-tailed deer, the most commonly hunted game in the United States.

On the opposite wall hangs Mcilvaine’s Worn in and Stretched Out, crafted in response to his experience with hunting as a means to assimilate into Midwestern culture. The collage of deconstructed Dickies and animal fur hang large and proud, carrying the weight of the first animal Mcilvaine hunted and killed at the age of 12—the antlers of a small white-tailed deer. Though Mcilvaine quit hunting at age 18, the relic holds a painful memory imbued with his innate reluctance towards violence. On top of the canvas, he places his first gold grill, a symbol of solidarity with the life taken and a commentary on how objects carry bodily memory even after its owner no longer has use for it.

Both artists challenge the idea that there is safety in hyper-masculinity. They do not shy away from the nuanced conversations about the harm inflicted on their bodies and psyche through Machismo culture and the adultification of young Black boys. Their works are a testament to an environment that pushed them into survival methods that made it necessary to embrace being the hunter, or accept being hunted.

Works like Marginalized, Migration, and Education implore viewers to consider what would happen if we questioned our systems, our leaders, our educators, and even ourselves about how language is one of society’s most oppressive tools.

With conviction, Demery declares that “language is aggressive”. Through his series of wooden children’s puzzles, Demery utilizes anagrams to shift the audience’s perception about words that we use daily. From the word “marginalized,” Demery offers “dream”; from “Europe,” we receive “pure”; and from “education,” we are left with “caution”—a reminder that subtle violence often starts in the places where the youngest of our communities frequent. Language permeates our consciousness and can shape our thoughts before we realize we’ve even formed an opinion.

The aesthetics of Demery and Mcilvane’s work is informed by the traumas that are inherent to the identities of being Black and/or Latino in the United States. They are particularly invested in revealing the complexities of people whose culture might be shaped by marginalization, but is not defined by it. Together, through the excavation of personal history, they project a collective narrative that ripples beyond the walls of the gallery. Their assemblages deify the objects used and ask the viewer to settle into the reality that to be Black and Brown in the United States is to constantly be in a state of flux.

I am grateful to the artists for reminding me that migration is an innate quality of all living creatures. I am rolling where the wind takes me; I am amplifying the voices of my ancestors.

Threshold II: Migration Patterns is on view at Gallery Bogart from April 6, 2024 to June 1, 2024.

About the Aathor: Kaitlyn B. Jones is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and independent curator committed to using art as a conduit for healing and a seedbed for activism. She is an avid writer whose scholarship is rooted in the intersections of Black-American history and contemporary art. Through a multimedia semiotic lens, she explores themes of legacy, lineage and autonomy as it relates to the conscious and unconscious value placed on the histories and multifaceted cultures of the Black Diaspora. She is the Founder and Chief Curator of Conduit Arts, a curatorial platform for research-based, community-oriented arts and culture projects that center Black diasporic histories, cultures, and perspectives.