Disclaimer: This writing does not reflect the opinions of the J. Paul Getty Trust/Getty Research Institute.

A few months ago, the Getty Research Institute’s team at the Johnson Publishing Company Archive (JPCA) discussed a folder of photographs used in a November 1954 Ebony feature on James McHarris, a Black man we’d consider today as transgender who was identified by his birth name in the article. One of the Processing Archivists, Naja Morris, wondered how to edit this folder title considering that Johnson Publishing Company (JPC) referred to McHarris by a name that he didn’t identify with. The Ebony article describes McHarris’s experiences living as a man, even featuring a photograph of him in women’s clothing with a quote of him describing his discomfort wearing them. As a Black transgender man myself, I had found this Ebony feature on McHarris years before while researching Black trans history for my personal memory work. McHarris’s story is actually cited often in circles of Black trans writers focusing on our histories. Personally knowing the harm of misgendering and deadnaming, I’m grateful for how my team navigated this aspect of reparative description that I’m leading as JPCA’s Archives Assistant.

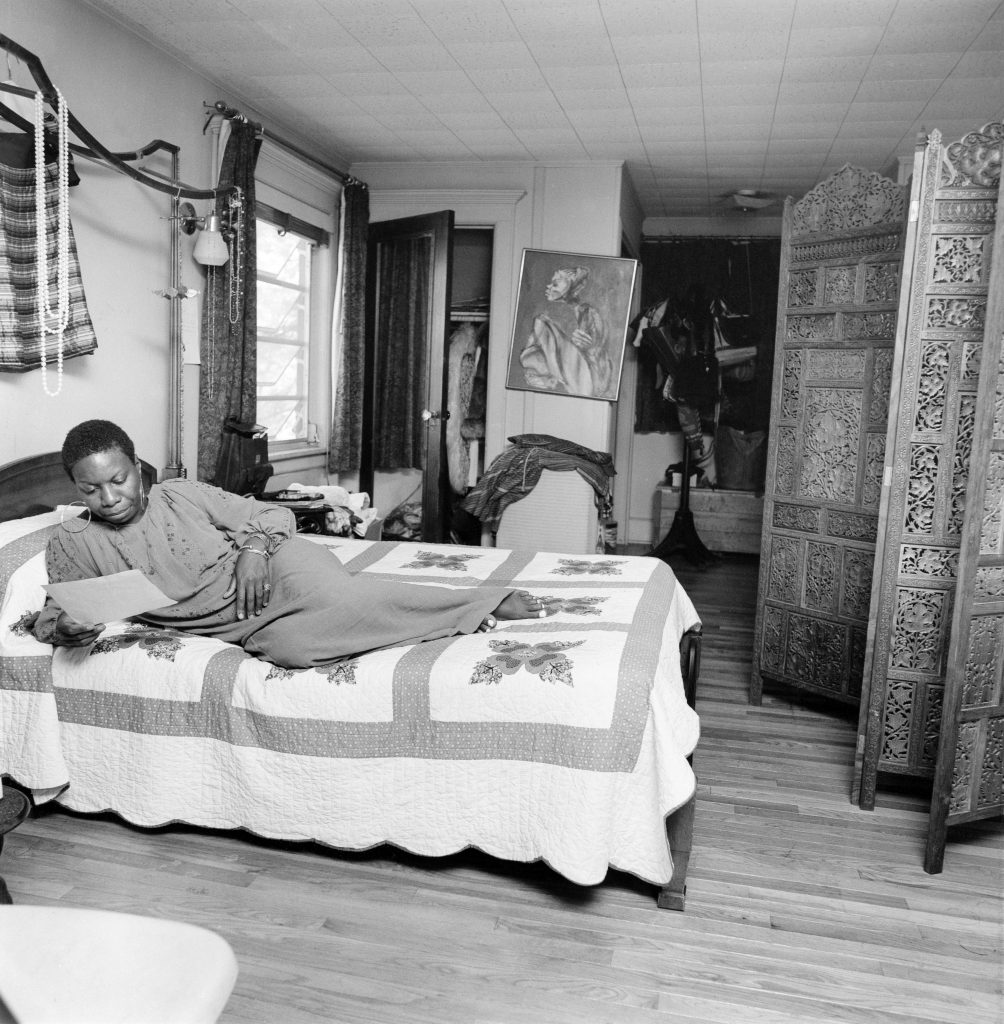

JPCA is the largest collection I’ve worked on, housing over four million images from the company that created Ebony, Jet, Ebony Fashion Fair, Fashion Fair Cosmetics, and several other publications and programs since its founding in 1942 by John H. Johnson. JPC transformed media representations of Black people with Johnson’s vision of publishing images reflecting joy and pride in his communities. Though many of the photographs feature celebrities, there are also plenty of images of everyday Black life and people who made significant impacts, regardless of fame or fortune. The company’s publications had undeniable impacts on how images of Black people and culture are created and shared today.

The photo collection at JPCA wasn’t considered an archive when it was a part of JPC—before their building at South Michigan Avenue closed and the photos were in active use. Under the Getty Research Institute’s management, these materials will be made accessible, as an archive, to the general public for the first time. From the 1940s into the early 2000s, JPC led changes in visual culture and the ways Black communities were represented in mass media by uplifting positive imagery of Black people. While the photos were cataloged by JPC standards, there are impacts on description and sensitive content that stem from oppressive systems intersecting with racism at the time, including ableism, homo- and transphobia, sexism, and much more. This means that some folder titles are outdated, dehumanizing, or inaccurate, and there are sensitive images needing content warnings or potential restrictions. I felt driven to address the needs of the people who’ll see the Archive in the future as well as the people in the photos calling on us as archivists to honor their legacies. When I joined JPCA to help prepare this historic photograph collection for the public, it became clear to me that many librarians and archivists today know the neutrality that traditional librarianship values is harmful because it ignores our experiences influencing our practices.

Images affect how communities are treated in society because culture, including visual culture, dictates the values that we hold individually and collectively. Photographs play important roles in both the ancestral rituals and political work that I do, driving my understanding of how visual memory promotes collective action for liberation. Archivists like Rachel E. Winston are calling for critical race praxis in archives, responding to demands of our field to act in solidarity with oppressed people. I’ve also learned from Dr. Tonia Sutherland’s scholarship around appropriate access when considering how to handle images of violence targeting Black people. This responsibility of radical care in archival work for the people shown in collections and those working with archives led me to learn more about reparative description and critical cataloging.

Critical Cataloging (or CritCat) and reparative description are practices of ethically editing or creating catalog records, finding aids, and other descriptive resources in libraries and archives that would otherwise be harmful, offensive, or inaccurate. Though neither practice is generally included in the curricula of library or museum studies graduate programs, there’s scholarship and programming to support this work. Both practices challenge traditional librarianship’s value of neutrality by shifting our focus toward empathy and accountability for our biases in practice. Our team of JPCA archivists worked through this decision in reparative description together, discussing the importance of naming James McHarris as he chose to self-identify while making sure that JPC’s actions are still documented to accurately reflect the company’s history.

Learning about CritCat and reparative description has resonated with me as an archivist both politically and spiritually. My interest in reparative description comes from experiencing first-hand the harmful effects of dehumanizing language or materials in archives as both a worker and researcher. Reparative description is about compassion for people using materials and the people or places represented in them.

To start the reparative description of the collection, I went through our folder inventories to flag titles for a pilot that would help me develop a workflow for our team of archivists. I researched reparative description guidelines at the Getty Research Institute, which manages our rehousing and cataloging of the collection, as well as guidelines from other relevant sources. The pilot sampled 2-3% of the folders to see a) if the images were published by JPC and b) whether the catalog records should be edited to be more accurate and/or ethical. This helped me create a plan for editing folder titles, restricting sensitive images, and creating content warnings while documenting our decisions.

Even with a plan in place, there have been challenges in navigating this work. It’s not always possible to know how someone chose to describe themselves, especially because many people in JPC’s photographs aren’t identified. We also have evidence that some people in the photographs chose to identify with language that is now outdated or harmful. For example, while “female impersonators” is now considered an offensive name for drag queens, there’s evidence in JPC publications that this was the preferred term by performers in the mid-1900s. We’ve also had important conversations about making the original prints of Emmett Till’s open casket photographs available, especially considering Mamie Till’s demand that the world see how violent white supremacists murdered her son.

Though I was glad to have a plan for reparative description, looking through these folders and making difficult decisions about how to handle harmful content was emotionally taxing in ways that our field isn’t prepared for. The emotional labor of creating reparative description processes while facing oppression ourselves is talked about often between archivists invested in this work, but rarely addressed by the whole field. I’m grateful to my manager, our team, and the community of archivists who I asked about how to honor the people in JPC’s photographs and the people who will see them, while also accurately representing the collection’s vast history.

Five months into reparative description work at JPCA, I had a meeting with our Content Review Working Group that includes our Archive Manager Steven D. Booth, our Processing Manager Skyla S. Hearn, and myself where we talked about the challenges we’ve had so far. We’re trying to determine the best ways to protect the people in photographs depicting death, violence, injury, nudity, etc., and minors in these contexts, while also preserving the context of JPC that produced these images. Navigating lessons from slow-archiving and centering compassion while still making sure we share materials in a timely manner is hard work.

Our working group navigates reparative description as people whose own histories are represented in the collection, meaning that these images affect us emotionally. Thanks to Booth’s suggestion, we review images flagged for sensitive and/or harmful content as a group. We work through challenges with compassion for each other as well as for the people represented in the photos and those eventually viewing them. The changes and additions we’ve made to our original plans have often come about when our archival team asks us important clarifying questions about our workflows, challenging us to reflect critically on the decisions we make. As we review images that our team flags for sensitive or harmful content, our working group has determined and re-determined what our best practices should be according to what we learn about the collection, grounding ourselves in our ethical archival values.

So far, JPCA’s processing manual guiding our workflows includes a content warning for our team of archivists about the sensitive and/or harmful content they might come across; instructions with a table for editing folder titles about people and subjects; instructions for flagging materials when sensitive images are found or folder titles needing editing aren’t included in the table; and instructions for our working group’s content reviews. We’ll be making recommendations for a collection stewardship group to carry on our work after rehousing and cataloging. Our Finding Aid Working Group will also accurately and ethically describe the collection for public access.

This work is fulfilling to me as an archivist rooting my practices in the spiritual and political values that guide my life as a memory worker because I believe that radical movements need to consider the lineages we’re part of and the histories we create. Memory work is spiritual for me because fighting oppression includes reconnecting people with traditions that improve their lives, including ancestral religions and spiritualities grounded in memory and grief. Archives impact history, history impacts society, and society is impacted by cultural practices and our dis/connections to them. Spiritual, political, and cultural values guide my life and drive my work in archives.

My hope for reparative description work at JPCA is that we can share how we engaged these practices proactively, especially as a collection created by Black people. At JPCA, we’re archiving with values extending from anti-racism with radical ethics against sexism, ableism, homo-/transphobia, and more. As an archivist, the care that guides my practice stems from my personal, political, and spiritual values. As a team of archivists who share compassion for the people represented in and eventually see these photographs, we hope to contribute a valuable perspective on reparative description from a historic collection of Black visual culture.

About the Author: Jehoiada Zechariah Calvin is a memory worker, writer, and zine-maker from Chicago. Jehoiada is the Archives Assistant for the Johnson Publishing Company Archive, helping to process the historic photograph collection for Ebony, Jet, and other magazines and programs. Jehoiada is a fellow in the University of Alabama’s Social Justice for Archivists Master of Library and Information Studies program, focusing on memory work that supports practices rooted in cultural traditions outside of institutional archives.