This essay is published as part of Sixty’s Midwest Arts Writers Fellowship, an opportunity for writers to develop, refine, and publish writings on topics that are relevant to Indigenous, trans, queer, diasporic, and/or disabled artists and arts workers in our region.

On one of the coldest days of the year in Minnesota this year, I visited the Walker Art Center and felt as if I was being drawn, summoned perhaps, into a void. I was disoriented by the stark contrast between the fluorescently lit museum hallways I’d just left and the darkened space I now found myself in. As part of Berlin-based artist Pan Daijing’s exhibition Sudden Places1, the artist transformed the gallery space with tar-impregnated felt and reduced lighting, drawing attention to the central work of the show—The Hour Between Dog and Wolf, a “meditation on the relationship between solitude and interdependence.” The title refers to dusk, the moment of transition between day and night when it’s difficult to distinguish between two things, for example: a dog and a wolf. Or perhaps a friend and a foe.

Afterward I reflected upon the constant shifts in our perception of the world around us. Daijing’s work transfixed me. I started to think about this desire to classify and its relationship to animism2—land, body, self, living and nonliving, permanence and impermanence—ideas that haunted me for the rest of the day.

Following Daijing’s exhibition, I continued to think about the burning issues surrounding the global climate catastrophe and the logic that makes this destruction possible—Earth ruptured, body ruptured. I want to resist this binary between earth and body, divine and human, to insist that the human is contained in the Earth in a spiritual union. Yet, I wonder where, if at all, technology relates to this divine connection.

Perhaps, like the hour between dog and wolf, the boundaries between these distinctions are blurred. I long for these blurred boundaries, which makes me feel like a shapeshifter. In Native mythology, the trickster is a character who can travel between two realms, a symbolic metaphor for the ambiguous, elusive, and transgressive. Like a modern day trickster, I want to be a digital creature, a cyborgian body detached from social structures—imagine the freedom I would possess! Maybe this is where things become paradoxical. How can I believe wholeheartedly in the Indigenous teachings of animism, of the 7 generations, of our responsibility to protect Unci Maka while desiring to merge human and machine?

Though, I would argue that despite our best efforts to check out, log off, detach, the technological and digital seeps into our lives, touching and mutating the way we perceive. As Sophie Strand says: “the truth is that we are [all] implicated molecularly with the world. There’s no exclusion zone.”3

With these antithetical longings riddling my mind, body, and spirit, I find myself drawn to artists who, as Glitch Feminism author Legacy Russell writes, “navigate the complicated and irreconcilable territories as sort of anarchitectural,” and represent the “self-chronicling of one’s own unresolved and often contradictory shapeshifting.”4

If we are indeed shapeshifting through our contradictions as a means to make sense of our self in relation to technology and transient nature, where does art come into play? While I feel compelled to investigate and reshape my relationship with technology, I also want to contemplate the shifts of time and space that occur within the techno-spiritual realm, the virtual, the digital. There has to be a spirituality within the techno. The cosmos is too tender to be without a conscience.

Do all artists interested in exploring ecology through their work have an inherent disdain and distrust for the technological world? Have digital artists forgotten the feeling of being haunted by a land? Will there always be a separation from the natural world and the techno realm, or can the technological be spiritual? Is there a way to harness the machine to deepen our understanding of ourselves and, in turn, our connection to non-human entities?

Exploring artists Sarah Rosalena, Katja Novitskova, and Miller Robinson, I find myself ruminating on their work, which merges these seemingly antithetical concepts, “reawakening kin who are already inside these technologies.”5 In other words, summoning the ancestors. Maybe that’s what the ancestors were waiting for all along, us to find the connective threads of technology, the natural world, and our bodies.

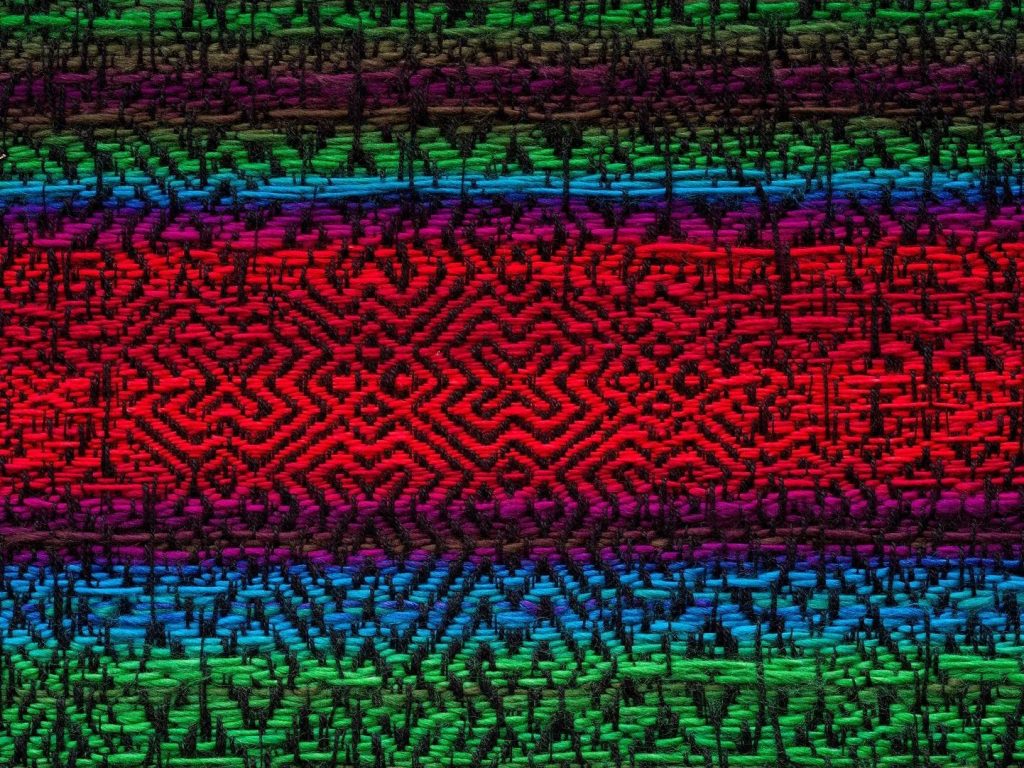

This metaphor of weaving and shapeshifting makes me think of Sarah Rosalena’s work. An interdisciplinary artist and weaver based in LA, Rosalena aims to deconstruct technology through Indigenous understandings of the non-linear. Integrating coding with textile, her work is a disruption of cartography, borders, and terrain. Creating new structures of hand and the machine, Rosalena’s signature textile pieces are crafted on a computer-sequined Jacquard loom, the pixelated squares of weavings finished by using natural fibers of indigo and cochineal-dyed yarns and pine needles to construct complex patterns. Her weavings explore Indigenous cosmologies, using storytelling and the traditional crafting methods that led to technological advancement to bring us into both worlds—to integrate both the digital and natural divine.

Scholar Elizabeth Povinelli argues that, “by integrating Indigenous patterns and craft techniques with Western technologies, Rosalena activates the nonliving kin.”5 Her computational, hybrid craft counters techno-solutionism, and challenges viewers to consider how traditional understanding of animism, in which non-human entities are seen as possessing agency and significance, could be applied to technology.

By weaving together Indigenous knowledge, perspectives, and traditional methods with technology, Rosalena calls for us to shift and subvert conventional and colonial narratives of climate justice. Rosalena’s artwork activates the destabilizing ambivalences that occur when binary structures collapse, specifically the divide between Western technologies and Indigenous/ancestral patterns and understanding of infinity. A kinship arises.

Indigenous writer Jas Morgan explains this kinship and its connection with Indigenous Futurism6, “every day, Indigenous peoples are restoring their beings, bodies, genders, sexualities, and reproductive lives from colonial institutions through play, self-representation, and sexual self-determination. Enacting kinship in their art, the Indigenous artists discussed here embody the past and future in their present representations, projecting decolonial love and kinship ways into the cosmos.”7

Exploring the Indigenous belief system of animism and kinship, this non-anthropocentric approach to thinking is crucial. It demands that we value more than just humans and recognize the interconnectedness of all beings, inviting us to shift away from a purely individualistic mindset and embrace a more inclusive understanding of existence. Acknowledging the significance of non-human entities, that every element of the natural and immaterial world possesses a spiritual essence, invokes a deeper respect for nature and recognizes our collective place within this vast ecological tapestry.

So, is a love affair with technology counterintuitive to a desire to be in dialogue with and protect our natural world? That depends on whether you fuck with techno-humanism or techno-animism. Techno-humanism elevates technology as a human experience enhance (think Black Mirror right-sided) where technology benefits humanity as opposed to a virtual bearer of disenchantment and detachment. Conversely, techno-animism calls for a reevaluation of our relationship with technology, insisting we remain attuned to the animating forces of the natural world and recognize the agency of all beings, both human and non-human. Techno-animism urges us to see beyond the mere functionality of technology and consider its impact on our understanding of nature itself. In a techno-driven, capitalist world, which will ultimately save us? Leaning in or logging out? Touching moss or touching screens?

Maybe a both/and situation. Maybe it depends on what we see first: friend or foe.

Or perhaps there’s a better question: What do we have to do for the land to want us back?

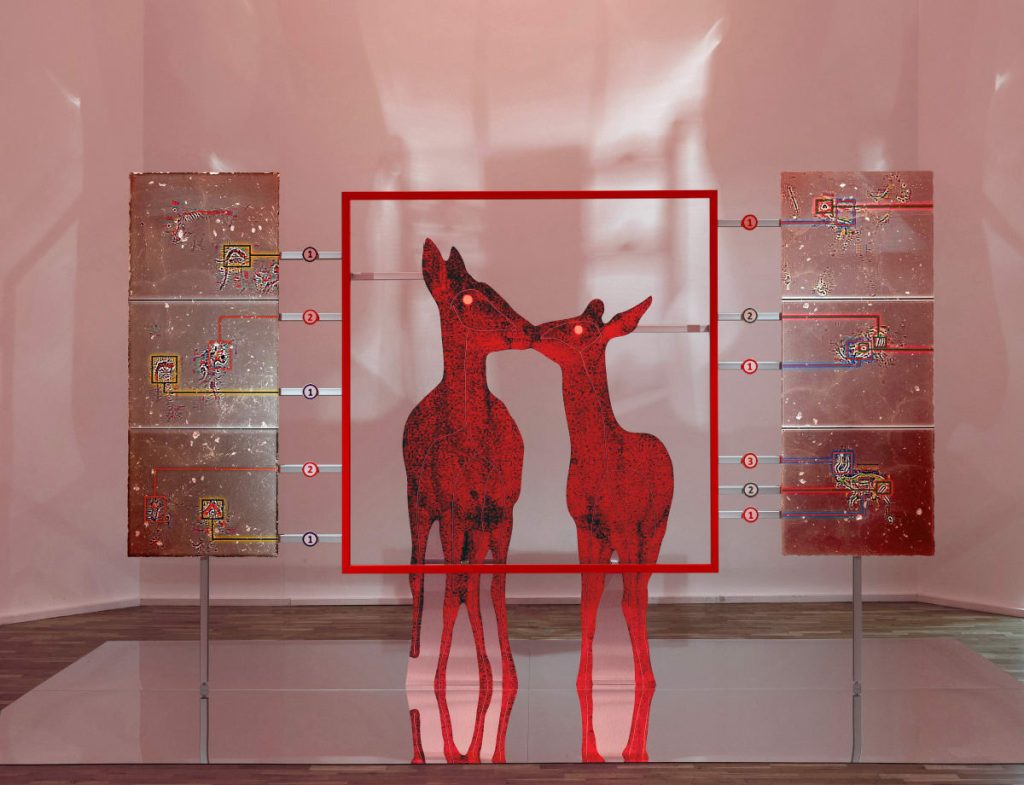

Artist Katja Novitskova, author of Post Internet Survival Guide, explores digital representations of nature and how they impact the way we perceive the world through them. Through imaging processing and an examination of digitally distorted images of nature, Novitskova’s work exists in the speculative near-future. Her installation work is part global collapse, part natural divide. Her synthetic territories and mutated ecosystems emerge from the intersection between technology and sentience, challenging how the artificial subverts the natural. Using AI as a playground, Novitskova blurs the boundaries between the digital and physical world, drawing found online images into the occupiable, tangible space. It leaves me thinking, if AI’s synthetic interpretations are more palpable than our reality, then where does the human imagination and the mind of the machine intersect? Kind of like a “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” query.

Similar to Rosalena, Novitskova’s work employs the concept of both/and by transcending the geontological divisions of life and non-life, blending the realms of art, science, and nature while dismissing narratives that are purely techno-solutionism driven. In this techno-spiritual world they create, there’s an invitation to succumb to vivid visions of the celestial while celebrating the ruptured body. They ask us to explore memory-keeping? What sacred legacy are we remembering? What residue of that memory will remain for future generations?

Working within these hybrid practices and paradoxes, Rosalena and Novitskova attempt to destabilize the context of conventional binaries: ancient/futuristic, handmade/autonomous, earthly/otherworldly, thereby opening portals to examine their artificially-enhanced, chimeric environment counterparts. Yet, they flow. They live in harmony, one not possessing more divine power than the other and not discrediting one another. Much like natural systems that don’t follow the borders imposed by humans as a means to control them. These works disrupt the colonial thinking of categorizing and disconnecting. They remind us that natural systems require connections between one another for survival.

Anishinaabe literary scholar and mother of Indigenous Futurism, Grace Dillon, calls this “Native slipstream,” a nonlinear, non-Western conceptualization of time in which pasts, presents and futures “flow together like a navigable stream.”8

Using emerging technologies and traditional craft techniques, Rosalena’s Above Below textile blends the handcrafted and the mind of the machine with slipstream mastery. She describes her textiles as “Continuous and not resolved, with potential for multidimensional expansion from the single point of origin.” Her weavings harness the digital skin of living entities, revealing the passage of past, present, and future time as spiraling, continuous, and existing within all of us.

Two-Spirit transdisciplinary artist, Miller Robinson (it/its/itself) is another artist working within the realms of non-anthropocentric sensibility and Native slipstreams. In Robinson’s artistic practice, there is an ongoing and dynamic dialogue between material and immaterial, between object and self.

In Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living, Robinson highlights the concepts of permanence and the interconnectedness of ourselves with the world around us. Using handcrafted, corporeal material objects — fishing lures, human blood, and hair — as an act of both personal ritual and evolutionary engagement, Robinson’s artifacts are meant to be activated and in constant, reflective dialogue through sensorial meditations and offerings that place the viewer in both time parallels and ephemeral environmental landscapes.

In Suit No. 5 (Salmon)” (2020, 2022) and “Xùupsach Sàanvakàapih, Amvamaan (Ancestor Suitskin, Salmon skin)” (2022), Robinson explores the non-anthropocentric and the importance of Indigenous cultural practices. Donning a body suit of silicone rubber treated and crafted to embody salmon skin, Robinson highlights the role salmon play in for Karuk and Yurok people as well as engages in the ever-evolving nature of life and self. By embracing non-linear timelines, much like the way salmon return to their original place of birth to spawn and then die, Robinson explores the complexities of experience, memory and cycles. Central themes such as growth, decay, transfiguration, and temporality emerge throughout its pieces, inviting viewers to engage with and challenge the intricate relationships between identity and the world around us.

As I start to awaken kin and see a portal into this techno-spiritual, techno-animistic world, my original contradictions –nature, the divine, the technological– become increasingly blurred. Maybe the land wants us back simply because of our curiosity to consider its needs, wants, and desires, because we can cry at a virtually-constructed flower just the same as its natural, tangible, petal-fallen counterpart. Maybe, to quote Sophie Strand again, “if we are going to survive, we are going to need to tie our roots to other roots,” whether physical seeds or coded text. And while tethered, we awaken the ancestors who tell us to inhabit everything that we interact with, for better or for worse. I am in everything, everything is in me.

* * *

This fellowship is made possible with support from Arts Midwest. Arts Midwest supports, informs, and celebrates Midwestern creativity. They build community and opportunity across Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin, the Native Nations that share this geography, and beyond. As one of six nonprofit United States Regional Arts Organizations, Arts Midwest works to strengthen local arts and culture efforts in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts, state agencies, private funders, and many others. Learn more at artsmidwest.org.

Footnotes

- Sudden Places, Pa Daijing, Walker Art Center

- The term “animism” is derived from the Latin word anima, which translates to “breath, spirit, and life.”

- Sophie Strand: Rewilding myths and storytelling, Green Dreamer Podcast, 2022

- Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, 2020

- The Relational Science of Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Sarah Rosalena’s Anti-Colonial Aesthetics, Columbus Museum of Art

- 6 Indigenous Futurism is a powerful movement that uses art, literature, and other media to challenge dominant narratives, promote Indigenous sovereignty, and envision a future where Indigenous knowledge and perspectives are valued and integrated into the broader world.

- Jas M. Morgan, “Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurisms,” Guts Magazine, 2016, https://gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures/

- Grace L. Dillon, “Imagining Indigenous Futurisms,” in Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction

About the author: Juleana Enright (they/them) is an Indigenous queer writer, curator, DJ and theatre artist living in Minneapolis. They are an enrolled member of the Lower Brulé tribe of the Lakota nation. Juleana is the Gallery and Programs Coordinator at All My Relations Arts. They have contributed to local platforms, MnArtists, Pride Magazine, mplsart, Primer and City Pages. Juleana has curated five art exhibitions as an independent curator and was the recipient of the Emerging Curators Institute 2020-21 Fellowship program. Juleana was part of the Writers Residency program at the Franconia Sculpture Park in 2021 and an MnArtist Writers Fellow in 2023. Through their practice, Juleana strives to examine the act of daily creation in the midst of great chaos.

About the illustrator: Diosa (Jasmina Cazacu) is a Spanish-Romanian illustrator and muralist. She uses surreal, dreamlike imagery to create fantastical scenes that dare her audience to challenge their perceptions, observe with wonder, and appreciate the magic that is always flourishing beneath the surface of the mundane. Diosa has displayed in galleries and painted murals internationally. Painting is her way of interacting with the world. She plans to continue her travels and the exchange of getting to know new places while leaving a bit of herself behind in each.